Looking back: Germany five years after Fukushima

The aftermath

On the days following 11 March, 2011, the world watched aghast as reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi power station in Japan melted down after being hit by an earthquake and a tsunami. The disaster deeply unsettled Germany, and caused an unusual swift policy reversal by Chancellor Merkel, a professional physicist. She formulated a new plan for an accelerated phase-out of nuclear power by 2022. Over 80 percent of parliamentarians voted for the bill in the Bundestag (federal parliament), underscoring the deep-seated scepticism against nuclear in German society, which had been a dominant feature in particular since the 1986 nuclear disaster in Chernobyl in today's Ukraine. Die Linke (Left Party) only objected because it wanted a faster exit and the measure’s inclusion in the constitution.

“As a scientist, Merkel understood climate change and the dangers of nuclear power,” Martin Faulstich, chairman of the German Advisory Council on the Environment (SRU), told the Clean Energy Wire in 2015. “But she thought there could never be a meltdown in advanced, developed countries like Germany or Japan. To her credit, when exactly that happened, she acted quickly and took steps that might not have been possible at a later point.”

As a result of the shift, the importance of nuclear power for Germany is falling rapidly, while the share of renewables has surged, as illustrated in CLEW's:

- Factsheet: Germany’s energy consumption and power mix in charts

- Dossier: Energiewende – the first four decades.

- Factsheet: The history behind Germany’s nuclear phase-out.

- Factsheet: Milestones of the Energiewende (highlights other key turning points in German energy policy).

Nuclear phase-out remains uncontested

To this day, the nuclear phase-out itself remains uncontested in Germany, and popular support for the Energiewende in general is very strong. For more details, read CLEW's

- Factsheet: Polls reveal citizens’ support for Energiewende

- Factsheet: What business thinks of the energy transition.

The utilities reacted to the 2011 acceleration of the nuclear phase-out with lawsuits worth billions of euros. The power plant operators argue the state must compensate them for lost earnings and investments made when nuclear power still looked to have a future in Germany. But Regine Günther, General Director Policy and Climate at WWF Germany, believes even the utilities do not question the phase-out in principle. "Are there any attempts to undo the exit? My impression is: no. The operators are happy to get rid of the stuff," says Günther, who is also a member of the government committee reviewing the financing of the nuclear exit. But courts are yet to rule on whether government acted legally in 2011, as CLEW's

The Fukushima disaster also left deep marks in Germany’s political landscape almost immediately. It helped sweep Germany’s first Green state premier, Winfried Kretschmann, to power in the wealthy, industrial state of Baden-Württemberg – a development the Economist called “sensational” . Then, nearly half of voters said energy was the most important election issue. Now, the two states – plus Saxony-Anhalt in the east – are preparing to head to the polls again on March 13. But this time round, priorities are very different, with the refugee crisis overshadowing all other issues. Find out more about Fukushimas impact on regional politics and the upcoming elections in CLEW's

- News Article: Energy policy sidelined in German regional elections, could be impacted by result.

- Factsheet: Key facts on German states voting on 13 March

Clean-up challenges

After the reinstatement of the nuclear exit, the question is no longer whether Germany’s future will be nuclear-free – or even when, since the government is committed to completing the phase-out by 2022. But the logistics of pulling the plug on what was until recently one of the country’s primary sources of power are proving an immense challenge for this part of the Energiewende. Legal hurdles, decommissioning technicalities, and above all the question where to store the radioactive waste and who will pay for it all, are the main issues at hand. Read all about the challenges of putting the phase-out into reality in CLEW's

Germany is in the rare position of knowing almost exactly how much radioactive waste it will have to store because the lifespan of its nuclear reactors is limited and the existing amount of waste is established. But questions over where to store it and how long it will take to load a final repository remain unanswered. CLEW's

- Factsheet: What to do with the nuclear waste – the storage question provides an overview of the problems involved.

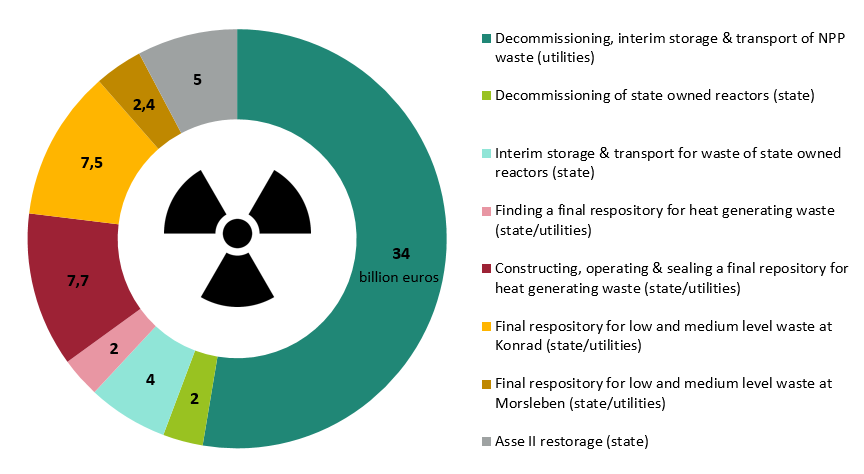

Decommissioning, storing, transporting and re-storing: Ridding Germany of its nuclear heritage comes with a hefty price tag. According to current estimates, costs will amount to over 65 billion euros. Some of the costs will be covered by the state but utilities are liable for most of the clean-up. CLEW's

- Factsheet: Nuclear clean-up costs adds up the bill.

Given the economic troubles of the power plant operators, it is questionable how much they will be able to pay for the nuclear legacy. New legislation on nuclear clean-up liabilities and a state-administered fund are under discussion to ensure the general public does not end up footing the bill. The

- Factsheet: Securing utility payments for the nuclear clean-up explains the battle lines.

Even if there is a broad consensus on the nuclear exit, the speed of the phase-out is not without critics in Germany. Some argue, for example, that the nuclear exit increases Germany’s dependence on fossil fuel imports. CLEW's

- Dossier: Energy transition shapes foreign policy in Germany and beyond and

- Factsheet: Germany’s dependence on imported fossil fuels take a closer look at the issues involved in this argument.

The next phase-out ahead?

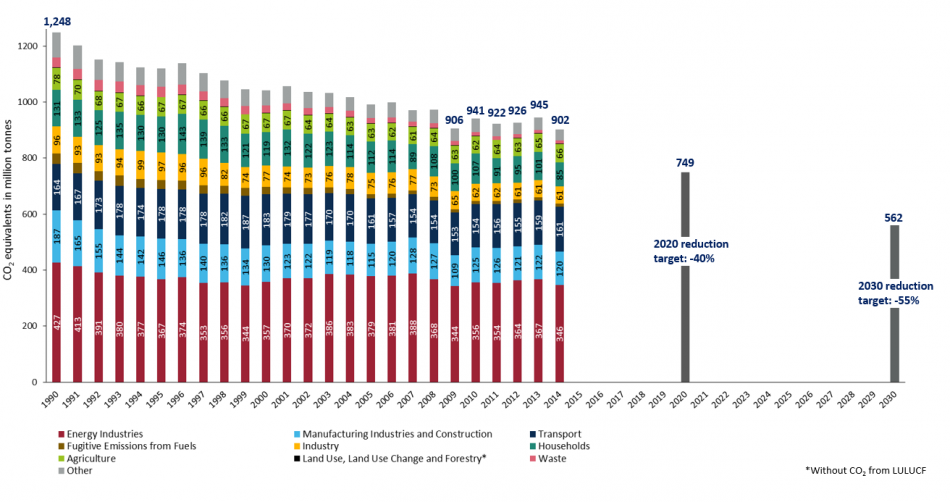

Some critics also blame the fact Germany has made scant progress in recent years in reducing its carbon footprint on the nuclear exit, as CO2-intensive power generation especially using coal continues to account for the largest share in the energy mix. In fact, emissions have changed little between 2009 and 2014, as the

Fears the nuclear exit would endanger the security of Germany’s power grid have been unfounded so far, as CLEW's

Partly as a result of the stubbornly high emission levels, the Energiewende debate in Germany has now shifted from the nuclear phase out to the long-term necessity to exit coal to achieve climate targets. The

- News Article: Environment minister says Germany needs plan to exit coal is a good starting point to look at this new debate.

External Content

German media have intensified their coverage of nuclear issues in the run-up to the Fukushima anniversary. Find CLEW's daily news digests here.

The Institute for Applied Ecology has produced an FAQ "Five years Fukushima" in German here.

Think tank Agora Energiewende has published an interactive overview over "Five years of energy transition after Fukushima" in English here.

Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) has published study evaluating the risks associated with Germany’s nuclear power plants, arguing the phase-out should happen even earlier than planned.

Events

Friends of the Earth Germany lists dozens of events related to the Fukushima and Chernobyl desasters here.

10 March: Greenpeace Energy press conference on Fukushima anniversary, in German, BERLIN.

22 March: The EU's Energy Transition at a cross-road: Where do we stand? How to transition cost-effectively to 2030? Lunch event by Agora Energiewende, BRUSSELS.

24 March: Friends of the Earth conference on "Learning from the nuclear disasters in Fukushima and Chernobyl", in German, BERLIN.