Q&A: The EU industrial carbon management strategy

Content

- Why is the EU working on an industrial carbon management strategy?

- How much CO2 will be captured in the EU?

- How much CO2 must be removed for EU greenhouse gas neutrality by 2050?

- How much CO2 will be stored in the EU?

- What is the role of CCS vs. CCU?

- What does the strategy say about transporting CO2?

- How can a European single market for industrial carbon management be financed?

- How do experts react to the strategy?

Find the Commission's press release, including the strategy, a factsheet and a Q&A from 6 February here.

Why is the EU working on an industrial carbon management (ICM) strategy?

The EU has set itself the target of making Europe the first greenhouse gas neutral continent by 2050. Simply reducing emissions step by step to eventually reach zero is not always possible, because a relevant amount is considered hard or impossible to abate with technologies known today. This is true for certain industrial processes, such as cement production, but also in agriculture – for example for methane emissions from cattle. The impact assessment for the Commission's 2040 greenhouse gas reduction target proposal says gross emissions will be reduced by about 92 percent by 2050 compared to 1990 levels, leaving 8 percent of residual emissions. These emissions must either be captured at the source – not a practical solution for the cattle – or an equal amount removed from the atmosphere, and then stored. The industrial carbon management (ICM) strategy says capturing and using or storing residual emissions from certain hard-to-abate sectors is key to decarbonising industry.

The EU can balance out the volume of remaining emissions by 2050 either through natural sinks like forests, or by technological means, such as direct air capture (DAC). Reports by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have said it will likely even be necessary to remove more from the atmosphere than is emitted to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak this century. Researchers have said that the EU must urgently set the right policy framework for novel carbon dioxide removals – such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) or DAC – to ensure that these can play a part in reaching the climate targets.

In the ICM, the European Commission itself says that the situation requires "a common and comprehensive policy and investment framework for all aspects of industrial carbon management." It says a European "single market for industrial carbon management solutions" is a key building block towards a climate-neutral economy in 2050, but makes clear that it has to be ramped up earlier.

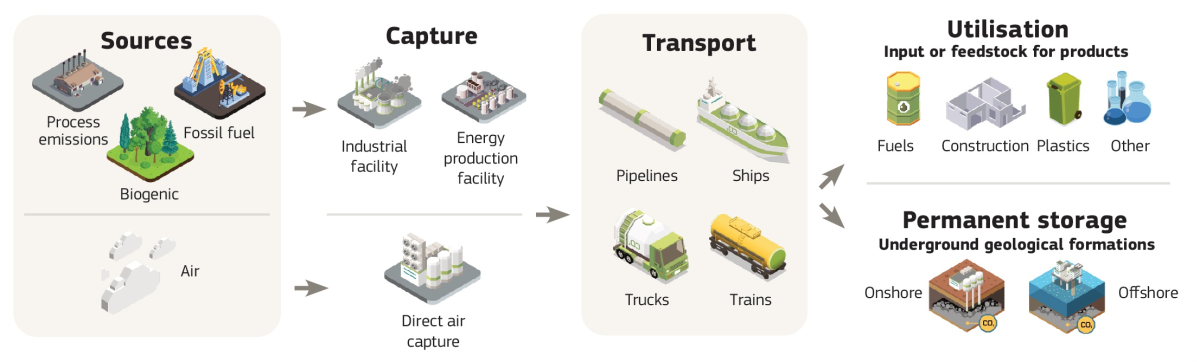

The Commission lays out three pathways for the EU-wide industrial carbon management strategy:

- CCS: capturing CO2 for storage, where emissions from fossil, biogenic or atmospheric origin are captured instead of released into the atmosphere, and transported for permanent storage

- Removal: removing CO2 from the atmosphere. Where permanent storage involves biogenic or atmospheric CO2 it will result in removal from the atmosphere

- CCU: capturing CO2 for utilisation, where industry uses captured CO2 to substitute fossil-based carbon in synthetic products or fuels.

Several EU member states are also working on national carbon management strategies, including France, Germany and Austria.

How much CO2 will be captured in the EU?

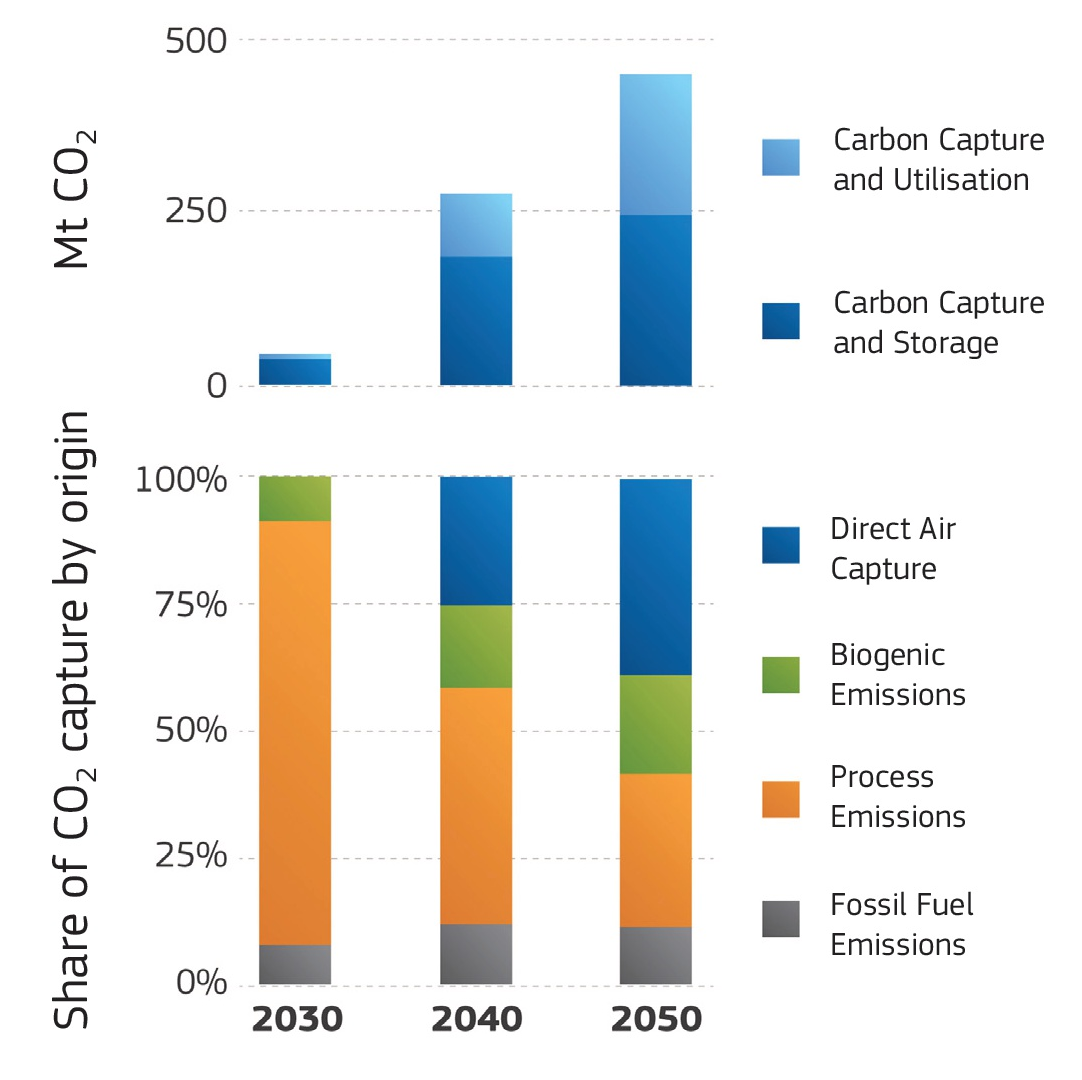

The ICM strategy says that the EU will need to be ready to capture at least 50 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2 annually by 2030, 280 Mt by 2040, and up to 450 Mt by 2050. Today, countries like France or Italy have total annual greenhouse gas emissions of around 400 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents.

The Commission's impact assessment on the 2040 climate target proposal sheds a light on where those emissions would be captured by 2050: The main sources are about 140 Mt from industrial processes, 55 Mt from fossil fuel power generation and 230 Mt from biomass power generation and direct air capture.

How much CO2 must be removed for EU greenhouse gas neutrality by 2050?

Overall, scenarios by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC) say that the EU could have residual gross greenhouse gas emissions of between 390 and 1,165 Mt of CO2 equivalents by 2050. The ICM strategy now says between 400 and 500 Mt would remain by that year. To reach net zero, these have to be balanced out – either through nature-based removals (e.g. forests, moorland) or technically as industrial carbon removals derived from carbon capture.

The Commission's impact assessment for the 2040 target assumes a little over 400 Mt by 2050 in a more ambitious scenario, and says that about three-quarters would be removed through nature-based solutions, and the remaining approximately 100 Mt technically. However, it emphasises that in the land use and land use change sector (LULUCF) – the nature-based removals such as through forests – "net removals have experienced rapid changes in the past years, and the future evolution of this sector is uncertain. The level can vary depending on the effect of policies or climate change impacts." The ESABCC scenarios assume LULUCF can remove anywhere between 100 and 400 Mt of CO2.

The EU could consider to set specific objectives for carbon removals, and include industrial carbon removals in the bloc's emissions trading system (EU ETS) or a connected mechanism, the Commission says. However, since especially direct air capture technologies are comparably expensive, "additional support" will be required at an early stage of deployment, it says.

How much CO2 will be stored in the EU?

The draft ICM strategy envisions annual CO2 injection capacity of about 50 Mt by 2030, and at least 250 Mt by 2040 across the entire European Economic Area, which – importantly – includes Norway, a CCS pioneer.

The paper says that two-thirds of EU member states allow CO2 storage on their territories. Until now, member states estimate an overall injection capacity of about 40 Mt by 2030. However, only Denmark, Italy and Netherlands have actually estimated annual CO2 injection capacity available in 2030, while several other EU countries are currently undergoing or planning to conduct assessments of their potential geological capacity.

By early 2026, the Commission aims to create an EU-wide "investment atlas of potential CO2 storage sites" to help investors identify opportunities. It calls on member states to include in their updated National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs, due by June 2024) their assessment of capture needs and storage capacity/options and identify actions to support the deployment of a CCS value chain.

What is the role of CCS vs. CCU?

The Commission's impact assessment for the upcoming 2040 climate target says that CCS is set to be deployed at large scale in the EU, with a steadily rising carbon price in the ETS as a key incentive. The scenario assumes that of the 450 Mt of CO2 captured per year by 2050, 250 Mt would be put in underground storage. This is also reflected in the carbon management strategy.

The rest would be used. The EU wants to "recycle" captured CO2 in the production of synthetic fuels (e-fuels) – for example for aviation – chemicals, or plastics to slowly replace the use of fossil fuel-based carbon, creating sustainable carbon cycles. The 2040 impact assessment says about 150 Mt would be used to produce e-fuels and 60 Mt to produce synthetic materials by mid-century.

Most of these products would release the carbon back into the atmosphere when used, while some would store it more permanently. There are already several EU rules that regulate the use of carbon, but "additional measures are needed to recognise the potential climate benefits of using sustainable carbon from captured CO2 rather than fossil carbon for other applications," the strategy says.

The Commission says the annual carbon demand for the chemical sector alone is currently estimated at around 125 Mt (450 Mt CO2 equivalent), and more than 90 percent is supplied from fossil fuels.

The strategy says the Commission will establish a framework for CCU "that tracks the source, transport and use of several hundred million tonnes of CO2, which should ensure environmental integrity and create price incentives to the extent the utilisation brings a climate benefit.

What does the strategy say about transporting CO2?

A cross-border, open access transport infrastructure is needed regardless of whether carbon is captured for storage or for use, the Commission says, adding that it would start work on a dedicated regulatory package to optimise its development. "It will consider issues including market and cost structure, cross-border integration and planning, technical harmonisation and investment incentives for new infrastructure, third-party access, competent regulatory authorities, tariff regulation and ownership models."

While there is already a market for CO2 today, volumes moved are very small compared to what is envisioned for the future, it says. A Commission study, mentioned in the ICM strategy, estimates that CO2 transport network, including pipelines and shipping routes, could span up to 7,300 km and deployment could cost up to 12.2 billion euros in total by 2030, rising to around 19,000 km and 16 billion euros in total by 2040.

By 2030, the first CO2 infrastructure hubs are expected to emerge, which would serve the carbon capture projects in existence then. By 2040, the Commission expects a number of regional carbon value chains to become economically viable, as CO2 becomes a "tradable commodity" for storage and use.

The Commission says that pipelines will often be the preferred – and overall dominant – transport means, but that construction faces significant hurdles due to costs and permitting. However, good coordination with the electricity, gas and hydrogen sectors could help use the full potential of repurposing and re-using the existing infrastructure.

The Commission also calls for "minimum CO2 stream quality standards" (composition, purity, pressure, temperature) to avoid interoperability issues also between countries.

How can a European single market for industrial carbon management be financed?

The Commission says that achieving the 2030 target of 50 Mt of storage capacity alone would require the industry to make investments worth 3 billion euros, with transport infrastructure coming on top with up to almost 10 billion euros. Beyond 2030, the Commission estimates that the required investment needs in CO2 transport infrastructure would rise to between 9.3 and 23.1 billion euros in 2050 to meet the 2040 and 2050 objectives. At the same time, a future CO2 value chain in the EU could be worth between 45 and 100 billion euros and could "help create between 75,000 and 170,000 jobs."

The Commission says that CO2 prices in the EU ETS will be a crucial driver to make CCS projects commercially viable, factoring in the costs of capture, transport, and storage of CO2 on the one hand and the price of emitting the same amount of CO2 on the other hand.

However, it also recognises that regulatory instruments as well as public financing is needed in addition to the industry's, especially in the early stages, to make it all profitable.

The EU funds CCUS projects through the ETS Innovation Fund – 28 projects have received almost 3.3 billion euros in grants to date. The Commission also proposes to launch funding calls for cross-border carbon dioxide transport infrastructure under the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) for Energy programme, which exists to implement the Trans-European Networks for Energy policy and has already funded CO2 projects with 680 million euros.

The EU allows state aid for CCS and CCU investments, and CCS is included in the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy, a system that defines companies’ activities as sustainable along several key objectives, including climate change mitigation. The Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA), where a final deal was negotiated in February, recognises CCS as a strategic net zero technology, which for example means projects could benefit from faster permitting procedures.

Finally, the Commission says member states themselves can supply state aid to CCS projects, either using EU funds from the coronavirus pandemic recovery mechanism (the Recovery and Resilience Facility, which runs out at the end of 2026), or their own budget. It proposes to consider whether certain carbon value chain projects could become so-called 'Important Projects of Common European Interest' (IPCEI), which would then be entitled to state aid.

The countries could also set up state-implemented "carbon contracts for difference" (CCfD). Here, subsidies cover the difference between a carbon reference price and an agreed 'strike price' representing the project's true costs.

How do experts react to the strategy?

"The outgoing Commission has strategically decided to give carbon management a very prominent role and is thus paving the way for a bridge between climate and industrial policy that will be of great importance in the coming years," said Felix Schenuit, researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP). Building up the necessary technologies to capture 280 Mt by 2040 and 450 Mt by 2050 would require "significant funds and support," he said in an e-mailed statement. Where the funding for projects is to come from and how distribution issues are to be resolved were two of the fundamental challenges for future carbon management policy.

In an op-ed in Tagesspiegel Background, Schenuit wrote that the "polarised debates" on CCS and CCU "will not get any easier" with the new EU proposal. In Germany, many stakeholders want to focus on hard-to-abate industry emissions, where the EU proposal is much more open.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) warns that the strategy proposal "bets on unproven technologies that could drive vast sums of public resources into inefficient projects." Andrew Reid, energy finance analyst, said that “the European Commission’s carbon capture ambition is significant at about 450 million tonnes of CO2 by 2050, of which around 40 percent will come from direct air capture (DAC) alone, the most expensive carbon capture process. DAC will require its own low-carbon energy and suitable storage sites to function. It costs anywhere from 600-1,000 US-dollars per tonne, considerably higher than the current EU Emissions Trading System or effective carbon price of around 60 euros.

German local utility association VKU said carbon capture can play an important role in waste incineration, where residual emissions are unavoidable. "Against this background, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) recently recommended that CCS be trialled at thermal waste treatment plants in the near future. We appeal to the government to create the legal conditions for this this year," said VKU.

Cement manufacturer Cemex welcomed the strategy. “The strategy is comprehensive and outlines relevant fields of action, but what is essential now is a timely implementation," said Martin Casey, Cemex Europe, Middle East and Africa communications director. "For companies to move forward, the regulatory framework regarding carbon capture and utilisation or storage, along with carbon accounting and removals, must be completed as a matter of the utmost urgency. The cement plant of 2030 is planned and designed today.”