Green pioneer Germany struggles to make climate protection a reality

Content:

United in theory, divided in practice

Climate action is now everyone’s concern

It’s all about coal

What is Germany’s role in the fight against climate change?

What targets for 2050?

Bringing climate change under control involves tough choices and requires a deep transformation, affecting each and every part of the economy. Germany woke up to these challenges in earnest when the government began to translate the Paris Climate Agreement into its Climate Action Plan 2050, detailing steps to wean the world’s fourth largest economy almost entirely off fossil fuels by mid-century, in line with its climate targets.

Only after months of heated controversy, behind-the-scenes manoeuvring and seesaw changes did the Climate Action Plan 2050 finally see the light of day – just in time for the Climate Summit in Marrakesh in November 2016.

The plan’s difficult birth immediately triggered fresh debate over whether it was up to the job of making the Paris Agreement a reality. Environmentalists said it didn’t go nearly far enough, while industry insisted it went too far – posing a threat to German competitiveness and jobs.

Environmental state secretary Jochen Flasbarth said controversy over the plan revealed that the Energiewende’s hardest challenges still lay ahead. “The period until 2020 is the easy bit,” Flasbarth said at a Climate-Alliance Germany event in late 2016.

United in theory, divided in practice

A vast majority of Germans are in favour of protecting the climate, a consensus that was underlined when German parliament unanimously ratified the Paris Climate Agreement in September. But that unity quickly falters when it comes to putting theory into practice with concrete measures.

Germany’s energy transition – or Energiewende – has made significant progress. The country now covers around a third of its electricity demand with renewables, and is on track to phase out nuclear power by 2022. But Germany’s track record on emissions reduction reveals a different picture, putting a question mark over the project’s success.

Germany’s CO2 emissions have fallen 27 percent since 1990, partly due to the collapse of East German industry after reunification. But in recent years, the country has struggled to achieve further reductions in line with its own climate targets, tarnishing its image as poster child of international decarbonisation efforts.

This is mainly because Germany hasn’t kicked its long-standing habit of burning coal – and particularly lignite (or brown coal) which is especially carbon-heavy – to generate power. Slow progress in other sectors, particularly transport and heating, has also been an important factor.

“We’re on track to spectacularly miss 2020 climate targets,” Regine Günther, climate expert at WWF Germany, said at a parliamentary hearing on climate policy in October 2016.

In December, leading experts commissioned by the economy ministry came to a similar conclusion, saying Germany would probably fail to meet several of its key energy transition targets for the year 2020.

Environmental NGO Germanwatch ranked Germany just 29th in its Climate Change Performance Index, citing lagging greenhouse gas emissions reduction and the lack of a clear roadmap for ending coal-fired power generation as preventing it from scoring higher. And even the government holds out little hope that 2020 goals of cutting emissions by 40 percent compared to 1990 will be met.

“Whereas global emissions fell in 2015, they went up in Germany. This doesn’t exactly support the notion that Germany is a pioneer,” Germanwatch head Christoph Bals said at the Climate-Alliance event.

Still, Environment Minister Barbara Hendricks, who tabled the Climate Action Plan, hopes the document will bring her country closer to its longer-term targets: Cutting emissions by 55 percent by 2030, and by 80 to 95 percent by 2050.

Following the Paris Agreement, Germany was the first country to spell out plans to reach long-term climate targets. Hendricks insisted that, “this Climate Action Plan is something we can be proud of at international level.”

The stakes are high for Germany, and for Angela Merkel, dubbed the “climate chancellor” after her push for international climate action in 2007. The Energiewende is under close scrutiny abroad as Germany hosts the G20 summit in 2017, with the general election in autumn 2017 focusing even more international attention on Germany – and complicating climate action in the short term.

Climate action is now everyone’s concern

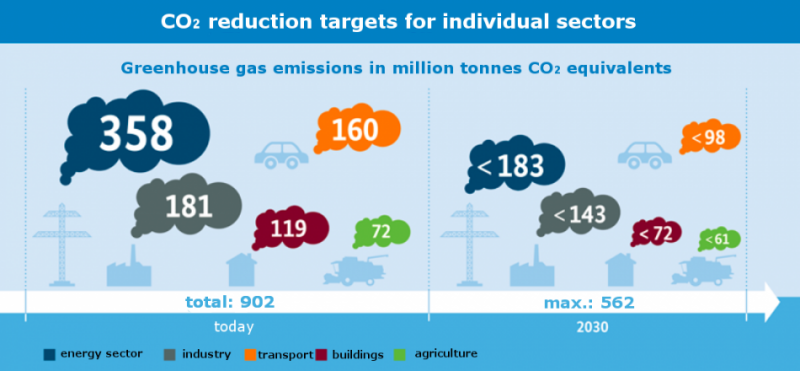

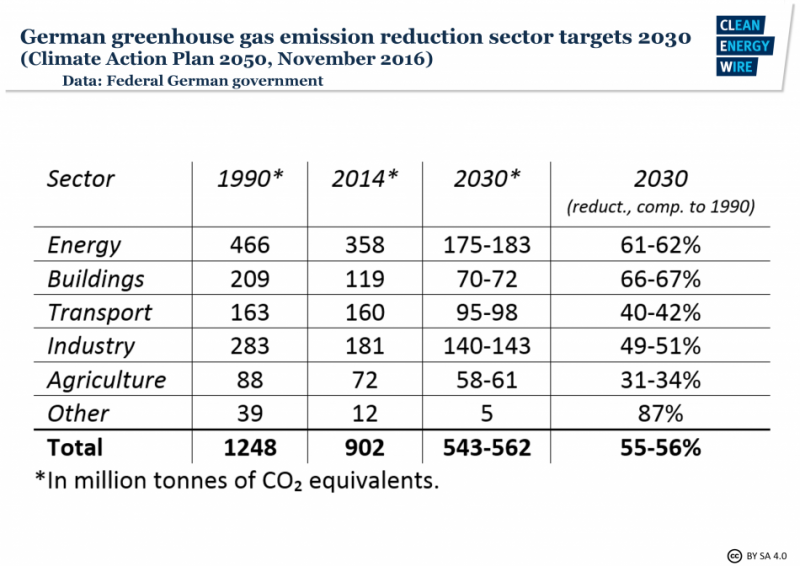

To bring the country back on track for its target to become virtually climate-neutral by mid-century, the climate plan spells out 2030 milestones for individual sectors of the economy for the first time.

“As of today, no one can fool themselves into thinking that climate action only affects others. I firmly believe that this plan is a historic turning point for climate policy in Germany,” Environment Minister Hendricks said on the plan’s publication.

Meeting these goals won’t be easy for any part of the economy – that much is already clear.

The energy sector – by far the largest CO2 culprit in Germany, responsible for almost 40 percent of the country’s total emissions – will have to halve its current greenhouse gas output by 2030, to less than 183 million tonnes. This is no mean feat and implies that half of Germany’s coal-fired power plants will have to be switched off by 2030, according to Hendricks.

How this is to be achieved remains unclear. In a research note for clients, Barclays bank utilities analyst Mark Lewis called the target “a very clear shot across the bows of high-carbon generation assets in Germany.” But he insisted that “if Germany is serious about meeting its emissions targets for 2030 and beyond it will have to set out a much clearer path for the decarbonisation of the power sector soon after next September’s federal election.”

Environmentalists are also alarmed that lack of detail might make it difficult to reach the power sector target. Oxfam climate expert Jan Kowalzig calls the omission of a clear exit scenario from coal the Climate Action Plan’s “main weakness”.

In transport, the plan calls for an emissions cut of 40 to 42 percent by 2030. This requires drastic change, because the sector has made virtually no headway at all in reducing its impact on the climate over the last 20 years. Every gain in vehicle efficiency has been eaten up by an increase in transport volume.

“The transport target is extremely ambitious,” Christian Hochfeld, head of transport think tank Agora Verkehrswende, told the Clean Energy Wire. He says cuts in transport emissions must be seen against a backdrop of a further massive increase in freight traffic volumes expected in the coming years.

Hochfeld believes it may be possible to reach the transport target without an initiative proposed by German states to end registrations of new cars with combustion engines by 2030. But greening the transport sector will still be a huge challenge for German carmakers. It is also a particularly delicate task for Germany as a whole, given that the car industry is one of the crown jewels of its economy and employs around 800,000 people.

The Climate Action Plan’s goal of cutting industry emissions by around 20 percent compared to today’s level sounds relatively easy. But some carbon-intensive industrial processes produce emissions that cannot be avoided by their very nature.

The head of Germany’s Steel Federation, Hans Jürgen Kerkhoff, said at the Tagesspigel newspaper’s Agenda 2017 event that cutting energy use was in any case a priority for energy-intensive industry, which had therefore done everything possible in this area. He warned against national measures that were not part of European – or ideally global – efforts because they “threatened the competitiveness” of the industry.

Reducing emission from buildings by 40 percent compared to today’s level will require massive investment in thermal insulation to reduce heating requirements. But the rate at which buildings are being refurbished to increase efficiency has lagged behind targets in recent years.

At the Tagesspiegel event, Michael Knipper, head of the construction industries association HDB, insisted that climate goals for the building sector were “unrealistic” and detrimental to the goal of providing urgently needed housing in German cities, because they drive up costs. He warned that the energy transition in the building sector must not burden those in need of accommodation.

Reducing the climate impact of agriculture is also a challenge, because there is no way to avoid methane emissions from animal husbandry. Put simply, cows will continue to fart regardless of regulations.

Germany’s minister for agriculture warned that “it remains uncertain whether we can achieve” sector targets. “We don’t know how technology will develop and therefore, we will have to adapt the targets.”

Originally, the plan was to suggest that Germans will need to cut their meat consumption by half, but this was dropped after media commentators warned citizens wouldn’t tolerate a “climate dictatorship.”

It’s all about coal

However tricky it might be to reach 2030 targets for all sectors, Germany’s goal is to become almost entirely carbon-neutral by 2050. Because unavoidable emissions in industry and agriculture will likely eat up Germany’s entire CO2 budget by mid-century, the target implies that all other sectors – electricity, transport, and heating – will have to run without causing any emissions whatsoever.

Government and analysts agree this can only be achieved if both transport and heating switch from oil and gas to renewables – either used directly as in heat pumps, or, for the most part, by integrating into the electricity system, a transformation dubbed “sector coupling.”

Given the resulting rise in demand for renewable power, critics wonder whether Germany’s recent reform of its core system of renewable financing might slow renewable development too much.

But above all, sector coupling makes emissions reductions in the electricity sector essential, and all the more urgent. There is no way around it: Germany has to face up to the fact it must kick its habit of burning coal to produce electricity.

“There is an unresolvable contradiction between using lignite for power generation and climate targets,” energy state secretary Rainer Baake said at the Climate-Alliance event.

Coal remains central to Germany’s power system, providing 42 percent of gross power production in 2015 – 18 percent from hard coal and 24 percent from lignite.

Yet setting out the details of how and when Germany is to ditch coal has been one of the most contentious issues of the Climate Action Plan.

Coal is mined domestically and tens of thousands of German jobs depend, directly or indirectly, on its extraction and consumption.

German hard coal can no longer compete with cheaper imports from abroad and the government has committed to closing the country’s last hard coal mine by 2018. But cheaper – and more climate-harmful – lignite has actually benefitted from the energy transition, as renewables have driven down wholesale power prices and pushed relatively clean natural gas out of the market. Lignite has made up the shortfall, resulting in the “Energiewende paradox”: Germany’s rapid development of renewable power has barely dented CO2 emissions.

Environment Minister Hendricks insists that a coal exit is implied in the plan. “If you read the Climate Action Plan carefully, you will find that the exit from coal-fired power generation is the immanent consequence of the energy sector target,” she said.

But due to strong resistance by mining unions, as well as regions economically dependent on coal, it omits a specific date when the last coal-fired power station is to go offline – leaving environmentalists frustrated, and a heated debate still raging over when Germany will finally say goodbye to coal.

Energy-intensive industry opposes a rapid coal phase-out because it is concerned this will push up costs and undermine international competitiveness. Even most environmentalists do not demand the plants be switched off within the next 10 years, and view 2030 or 2035 as a reasonable deadline.

Energy minister Sigmar Gabriel said it was unlikely that Germany’s last lignite power plants would go offline before the 2040s: “Lignite will definitely not be switched off in the coming decade. And I don’t believe that it will happen in the decade after that, either.”

For more on the debate over coal, see the CLEW factsheet: When will Germany finally ditch coal?

What is Germany’s role in the fight against climate change?

The wrangling over a coal exit in Germany belies a more fundamental dispute about the priorities for German climate policy. Environmentalists and industry tend to agree that Germany’s most important role in the fight against climate change is to set an example to the rest of the world. Given the country’s share of global emissions is around 2 percent it can do relatively little to mitigate climate change by itself.

But there is profound disagreement over the implications of Germany’s international role. Proponents of ambitious national climate policy believe Germany must prioritise cutting emissions in order to preserve its credibility as a climate pioneer, and prove to other countries that even an advanced industrial economy can pursue ambitious targets.

They argue this approach will also benefit the economy in the long run. “Climate protection brings huge benefits and innovations to the economy,” said DIW’s Kemfert.

Christine Nallinger, who heads Foundation 2°C, a business initiative for climate action, warned at the parliamentary hearing that without ambitious plans to reduce CO2 emissions Germany risks falling behind countries like China. “Companies want Germany to lead the way,” Nallinger said.

At the same event, Hubert Weiger, head of Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND), also stressed the economic benefits of bold action on climate protection.

“The earlier we set the course to cut emissions, the better for our economy,” Weiger said. “We will only be able to stand our ground in world markets if we make full use of the innovative potential that an ambitious climate policy brings for all sectors of the economy.”

Opponents of ambitious national climate policy – such as energy-intensive industry – on the other hand, maintain that Germany must prioritise economic development, to show it is possible to preserve its status as an economic powerhouse while cutting emissions.

“We have to show that it works economically, otherwise there will be no imitators,” said Andreas Theuer, head of climate protection at ThyssenKrupp Steel Europe, at the hearing.

There is little disagreement that Germany needs to prove that the shift to a climate-friendly economy can be an economic success story, an idea echoed by energy state secretary Baake at the Climate-Alliance event.

“The world is looking at Germany and wonders: ‘Will they manage climate protection without putting off businesses?’” Baake said. “The energy transition must become not only a success in the ecological sense, but also in economic sense. Otherwise, other countries will not follow us.”

Carsten Rolle, the industry association BDI's energy and climate expert, concedes that climate policy can bring economic opportunities for German companies, because they command roughly 15 percent of the global market for products related to energy and the environment. “The development of these markets, where we’re positioned very well, offers opportunities. But there are also a whole slew of risks,” said Rolle. “We need to take the costs into account.”

ThyssenKrupp’s Theuer rejected the “primacy” and “nationalisation” of climate policy, warning that Germany “can’t permanently drive ahead if others don’t come along.”

“It is right that industrialised nations should march ahead on climate protection,” said Rolle. “But we need a level playing field between countries in direct competition.”

Rolle says Germany’s G20 presidency is an excellent opportunity to agree on international climate action measures, such as a price for CO2 emissions. “Otherwise, we will just see displacement of businesses. We already see a subtle but permanent investment leakage.”

But Nallinger lamented during the hearing that the public debate on climate protection is often dominated by worries about the associated costs, instead of focusing on opportunities. “When it comes to the energy transition, everybody keeps talking about ‘costs’ – but in the end, we’re talking about investment in new infrastructure, and it’s also about jobs that are created by this transformation.”

What targets for 2050?

Given these contrasting viewpoints, there is no end in sight in the battle over Germany’s climate policies. The next dispute is already on the horizon. It concerns the objectives beyond 2020 and 2030: What climate targets should Germany pursue for 2050?

Bals told parliamentarians that given Germany’s economic strength and the EU-wide target of an 80-95 percent emissions reduction, the country needs to go well beyond a cut of 80 percent.

The WWF’s Günther insisted that a 95 percent cut must be the “core orientation” for 2050. “80 percent is obsolete,” she said.

Rolle warned at the same hearing that pursuing the 95 percent target would require twice as much in investment than an 80 percent target. “Especially for industry, the difference is enormous.”

With a view to this debate, industry think tank IW Köln also insisted that Germany “needs to strike a balance between ecologic ambition and economic capacity.”

The road to Germany’s climate-neutrality by mid-century will continue to lead through difficult terrain, and it is very possible that future politicians will come to realise see the period before 2030 as the easy bit – compared to what lies ahead.