Q&A – Germany faces heated debates over climate policy in 2024 EU election

This Q&A is part of a series from several countries highlighting the role and relevance of the European elections in 2024 into shaping climate and energy policy in the 27-member bloc. More will be published in the coming days. Find the Q&A on France here, and the Q&A on Croatia here.

Content

- Which European climate and energy policy debates are important in Germany’s national conversation?

- What role will climate and energy policy play in election campaigns?

- What role did climate and energy policy play in how Germany voted in the 2019 European elections?

- How important are European parliamentary elections in Germany?

- Who gets to vote and how does the system work?

1. Which European climate and energy policy debates are important in Germany’s national conversation?

Germany’s public political debate over the past two years has been dominated by climate and energy issues, closely linked to what was happening in the rest of Europe. When the new government entered into power in late 2021, it made the implementation of the country’s move to climate neutrality by 2045 and the necessary modernisation of economy and society the focus of its coalition agreement. At the same time, the government has insisted on using fossil gas as a bridging fuel for the energy transition. This led to tensions at the European level, when Germany pushed to include gas in the taxonomy for sustainable investments.

Less than three months after the government took office, Russia invaded Ukraine and Germany was at the centre of the energy crisis which was fuelled by the war throughout 2022. The country’s decades-long reliance on comparatively cheap Russian fossil gas meant that, for months, debates have been dominated by issues such as the fear of a recession, building up a liquefied natural gas (LNG) import infrastructure, and speeding up the expansion of renewables.

German decisions were deeply interwoven with those by the EU or neighbouring member states and influenced each other. In line with most other EU countries, Scholz’s government decided to end the dependence on Russia, while seeking alternative supply on the global markets. Germany’s billion-euro relief packages often put the country at odds with neighbours who could not afford that level of support.

In addition, car-loving Germany has seen intensive debates about new EU rules for vehicle emissions. While former leader Angela Merkel was labelled ‘auto industry chancellor’ after reportedly personally intervening in 2013 to prevent stricter CO2 limits for cars at EU level, the current government coalition earlier this year infamously threatened to withdraw its consent for the previously-agreed 2035 combustion engine phase-out – which angered some EU partners. Germany dropped its opposition after a deal was reached on how cars running on e-fuels would be allowed, but the move might have severe consequences on how the EU comes to legislative decisions.

While the student climate protests led by the Fridays for Future group helped put the threat of climate change on people’s minds and pushed decision makers to increase ambition, more drastic climate protests like the actions by the group Last Generation have faced broad criticism in the population in the past months. Protesters across Europe have thrown soup at famous paintings, chained themselves to airplanes, and turned the water of Rome’s iconic Trevi fountain black. In Germany, activists from Last Generation disrupted traffic by gluing themselves to roads. Surveys suggest that most people in the country believe that radical protests are obstructing the acceptance of effective climate action rather than supporting it.

At the national level, the government proposal for a de-facto ban of new oil and gas heaters from as early as next year has caused controversy within the ruling coalition, but has also been heatedly debated in public. Citizens worry about the costs of climate action in their homes, while industry and policymakers argue about the feasibility and timeline of government plans. EU negotiations on new rules for the energy performance of buildings are closely linked, as the German government is seeking rules that “do not overburden anyone”.

Graph shows survey results to question "What are 2 most important issues facing Germany" 2000-2023. Source: Forschungsgruppe Wahlen/CLEW.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/forschungsgruppewahlen-trend-important-issues-survey-germany_1.png?itok=5J9MfVYB)

2. What role will climate and energy policy play in election campaigns?

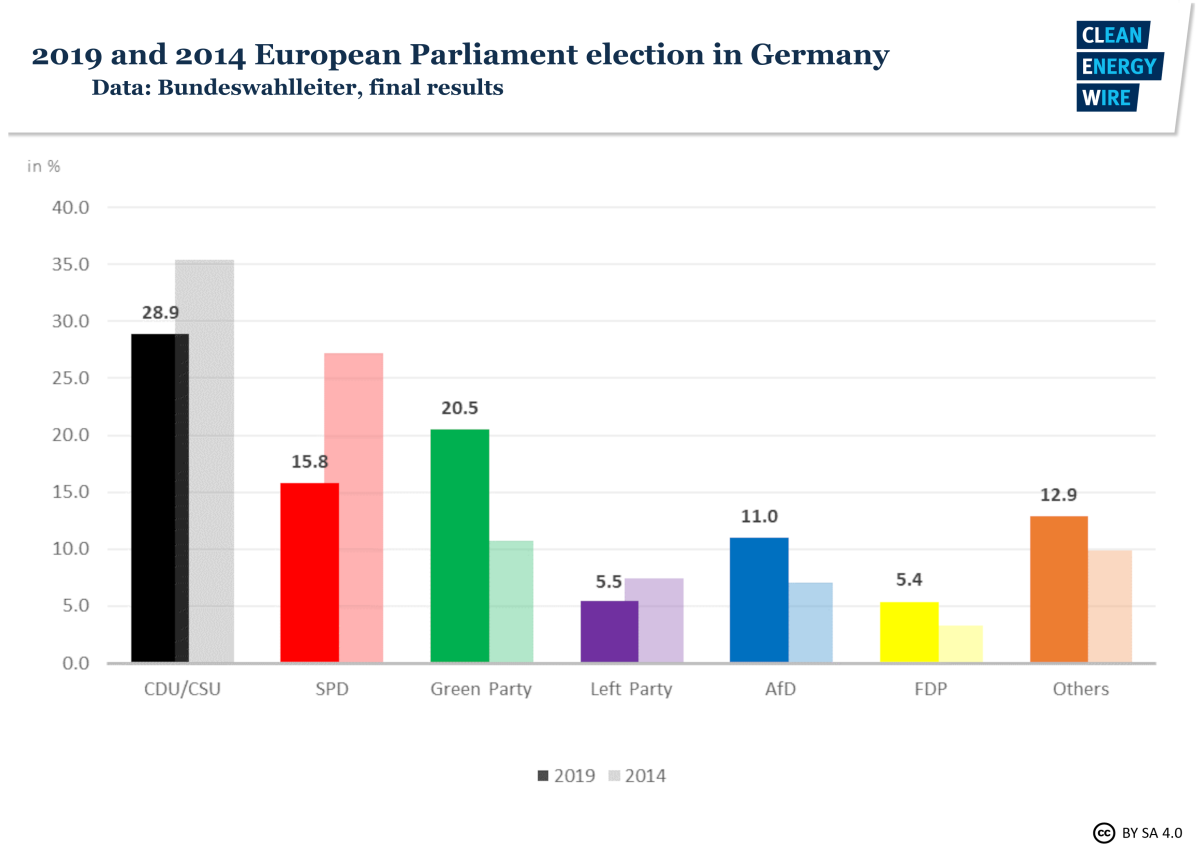

Commentators called the 2019 European vote a “climate election” in Germany. It delivered major gains for the Green Party as climate action topped the list of topics which influenced voter decisions. However, it took place in a conducive environment: Following the previous summer’s heatwaves, young activists from the Fridays for Future movement had for months been calling for more action against climate change with weekly protests across the EU, and put pressure on their governments to step up their climate ambition. Catastrophic floods in Germany and neighbouring countries in summer 2021 again made the effects of climate change a key worry of citizens, and polls show that climate and energy have remained near or at the top of people’s agenda in Germany for the past 5 years.

However, other issues have come up in the past years, including the pandemic or security worries following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Worries about inflation amid the energy crisis and the general costs of living – especially electricity, heating and transport – currently top the list of biggest issues in the mind of voters.

In addition, citizens are increasingly worried about negative effects the transition to climate neutrality could have on their individual lives – which is set to influence election campaigns. Fears over high costs and anger about government mandates sparked heated debates about a coalition proposal to ban new oil and gas boilers as early as next year.

Populists and the extreme right have a track record of using people’s worries and fears in election campaigns. This could become all the more important as voters in several eastern German states also head to the polls next year – Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia hold regional elections in autumn. Far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is especially high in the polls in these states.

3. What role did climate and energy policy play in how Germany voted in the 2019 European elections?

The European Parliament’s Post-Election Eurobarometer survey showed that about half of voters in Germany (51%) named protecting the environment and fighting against climate change as a key issue on which they based their decision. This was followed by human rights/democracy and how the EU should function in the future (both 42%). A poll by Infratest dimap for public broadcaster ARD also showed climate and environment protection on top with 48 percent (+28 percentage points compared to 2014), followed by social security (43%) and securing peace (35%).

Surveys showed a surge in worries starting in late 2018 about the effect of climate change. This was driven by exceptionally warm summers with drought and other effects, the Fridays for Future climate protest movement, and intense public debates about policies such as the coal exit. The coronavirus pandemic caused the issue to drop significantly for several months, but it has since come back to top the list.

4. How important are European parliamentary elections in Germany?

Political jobs in the European Union – be it members of parliament or commissioners – were for some time labelled as posts for those politicians whose careers had effectively already come to an end (“Hast Du einen Opa, schick ihn nach Europa” – ‘If you have a grandpa, send him to Europe’ – was a well-known rhyme). However, the EU today is an attractive work environment for German politicians, whether it is in leading positions (Commission president Ursula von der Leyen or former Parliament president Martin Schulz), or as an early career stepping stone.

Hast Du einen Opa, schick ihn nach Europa.

Still, polls show that many citizens see the European elections as less important than national, state or municipal votes and often do not know EU politicians. Voter turnout for the European elections has in the past always been much lower than that for national elections. Turnout in the first two decades of the 2000s remained at around 45 percent, until it spiked at 61.4 percent for the last vote in 2019, higher than the 51-percent EU-wide value. Voter turnout for recent national parliamentary elections was higher than 75 percent.

All major parties had a Europe-focused campaign in 2019, either with true EU issues, such as refugees in the Mediterranean, or with a European view on topics the parties stand for. The Left Party, for example, put a spotlight on taxing large corporations; the Greens advertised to “build the new Europe” in a climate-friendly way; and the FDP highlighted freedom and human rights.

5. Who gets to vote and how does the system work?

Germany sends 96 elected officials to the European Parliament, the most of all member states. They are elected based on party lists. The parties can either present one national list of candidates in all federal states, or separate for each state (traditionally, only CDU and CSU use state lists). There is no electoral threshold for the 2024 election, but EU regulation and plans by the German government to introduce one will change that in the future. Voting is not compulsory.

Citizens of the European Union with residence in Germany are eligible to vote if they are at least 16 years old, and have resided in the country for at least three months. Voters in Germany traditionally head to the polls on a Sunday. Thus, like in most EU member states, the election is set to take place on 9 June 2024.

Germans who live in another EU member state can either cast their vote there, under the respective rules, or choose to apply to vote in Germany – but they may only vote once.

German voters who live outside the EU and are no longer registered in Germany can vote in a European election, but they must submit a formal application for registration on the electoral roll before each election. There are certain conditions that must be met, such as having spent 3 consecutive months in Germany within the past 25 years, or being personally affected by the political conditions in Germany.