Q&A: Is Germany reverting to coal to fight the gas supply crunch?

Why is Germany permitting coal power stations to come back online and what does that mean for the coal phase-out plan?

Germany is facing a winter of very high energy prices and gas shortages due to Russia’s war against Ukraine and the related energy commodity embargos and gas delivery cuts. To substitute Russian gas (which usually comes via pipeline), the government has initiated a build-up of infrastructure for receiving liquified natural gas (LNG). However, not enough gas is expected to be sourced this way over the coming winter, meaning major energy savings and other measures will be necessary. In the months leading up to the height of the heating season, gas storages are being filled as much as possible.

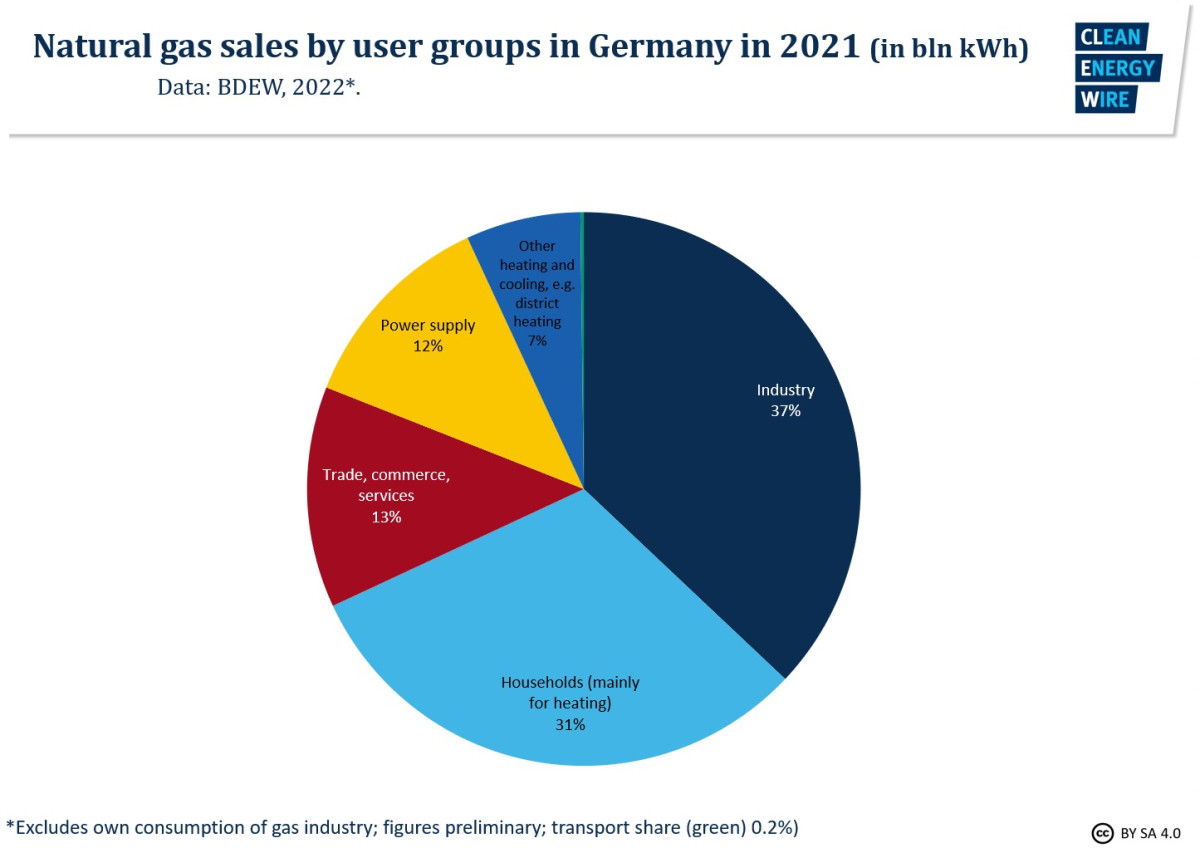

Natural gas accounted for nearly 27 percent of Germany’s total energy consumption in 2021, and was mostly used for heating houses (31%) and industry (37%) purposes. To a much lower extent, it was also used for electricity production (around 12%), mainly to balance demand peaks with plants that are able to respond quickly to market movements. The majority of natural gas is used for heating processes, either to generate the high temperatures needed for heavy industry, or for heating homes, offices and public buildings. In the power sector, gas is often used in combined heat and power plants, supplying not only electricity but also heat for cities’ district heating networks.

While this means that the greatest impact of the gas shortage (and the largest opportunities for saving gas) will occur in the industry sector, reducing the use of gas to generate electricity can also contribute to lower overall demand. The government therefore decided to allow mothballed coal power stations to be temporarily reactivated to help reduce natural gas consumption in the electricity sector. Due to the high gas prices, coal plants should push gas out of the market.

The Substitute Power Plants Maintenance Act (EKBG) stipulates that these plants, which have been retired under Germany’s coal phase-out scheme, can re-enter the power market for a limited period. With a subsequent regulation, the government said market participation is voluntary and will be limited until 30 April 2023. It was later extended to 31 March 2024. The economy and climate ministry said that the goal of phasing out coal use for power generation ideally by 2030 (and by 2038 at the very latest), remains unaffected, as do the climate targets.

Which coal plants are going to be running again first and when?

The EKBG provides for the use of coal plants that are part of Germany’s back-up fossil fuel power station reserves. Plants in these reserves are not permitted to take part in the normal power market (i.e. they cannot produce electricity and sell it on the exchange), but can be called to generate electricity by transmission grid operators to stabilise the power grid (grid reserve) or in the case of a severe supply shortage (lignite security standby).

Grid reserve: The grid reserve contains plants that are scheduled for temporary or permanent retirement but are classified by grid operators as systemically important and therefore must remain on stand-by. Plants in the grid reserve have a total capacity of 7,293 megawatt (MW), more than half of which being hard coal units. So far, these mostly run only a few hours per year to stabilise the grid in the event of high renewable power input in the north and power line bottlenecks to the south (re-dispatch).

Security standby: The so-called security standby was set up as a storage track for lignite plants retired as part of a 2014 climate action policy programme. Eight lignite blocks with a total capacity of 2.7 GW have been transferred to the security reserve, awaiting complete retirement after four years. Three of these units had already been retired by May 2022. The plants’ operators receive a total of 1.61 billion euros for putting the blocks in the reserve and must ensure that the plants can be operational within 10 days if needed. Since the establishment of the security standby, it has not been used once (as of April 2021).

The EKBG stipulates that as a first step, non-gas fired power plants from the grid reserve can be accepted back on the electricity market if the alert stage or the emergency stage of the national gas supply security plan are initiated. The (second highest) alert stage was called on 24 June 2022.

The installed capacity in the grid reserve totals about 4.3 GW of hard coal plants and 1.6 GW of mineral oil plants. In addition, the hard coal plants that have participated in a tender for payment in return for their retirement (under the German coal exit), which would come into effect in 2022 and 2023, will also be added to the grid reserve. Their capacity amounts to 2.1 GW in 2022 and another 0.5 GW in 2023.

On 21 July, the economy ministry announced that if hard coal and oil power plants do not contribute sufficiently to saving gas in power generation, then plants from the security standby will be called up to replace gas-power in the system. The government is working on the corresponding regulation, which will allow these lignite plants to come back from 1 October.

Letting the plants operate again will save some 5-10 TWh of natural gas over the next winter in Germany and a similar amount across Europe.

How will the power stations re-enter the market?

Once the alert stage of the gas supply security plan is announced, the government issues a statutory order that allows power plants from the grid reserve to participate in the electricity market for a fixed period of time. The government issued this order on 13 July. The whole scheme is temporary, and it is scheduled to end on 31 March 2024. Operators are free to decide whether they want to reactivate the plants and operate on the electricity market, experts expect them to do so due to the high power prices, according to a report in newspaper Tagesspiegel.

On 1 August, operator EPH announced the first hard coal plant (Mehrum in Lower Saxony) that was mothballed in 2021 as being ready to restart operations.

What contribution can hard coal and lignite plants make to saving gas? What role do combined heat and power plants (CHP) play?

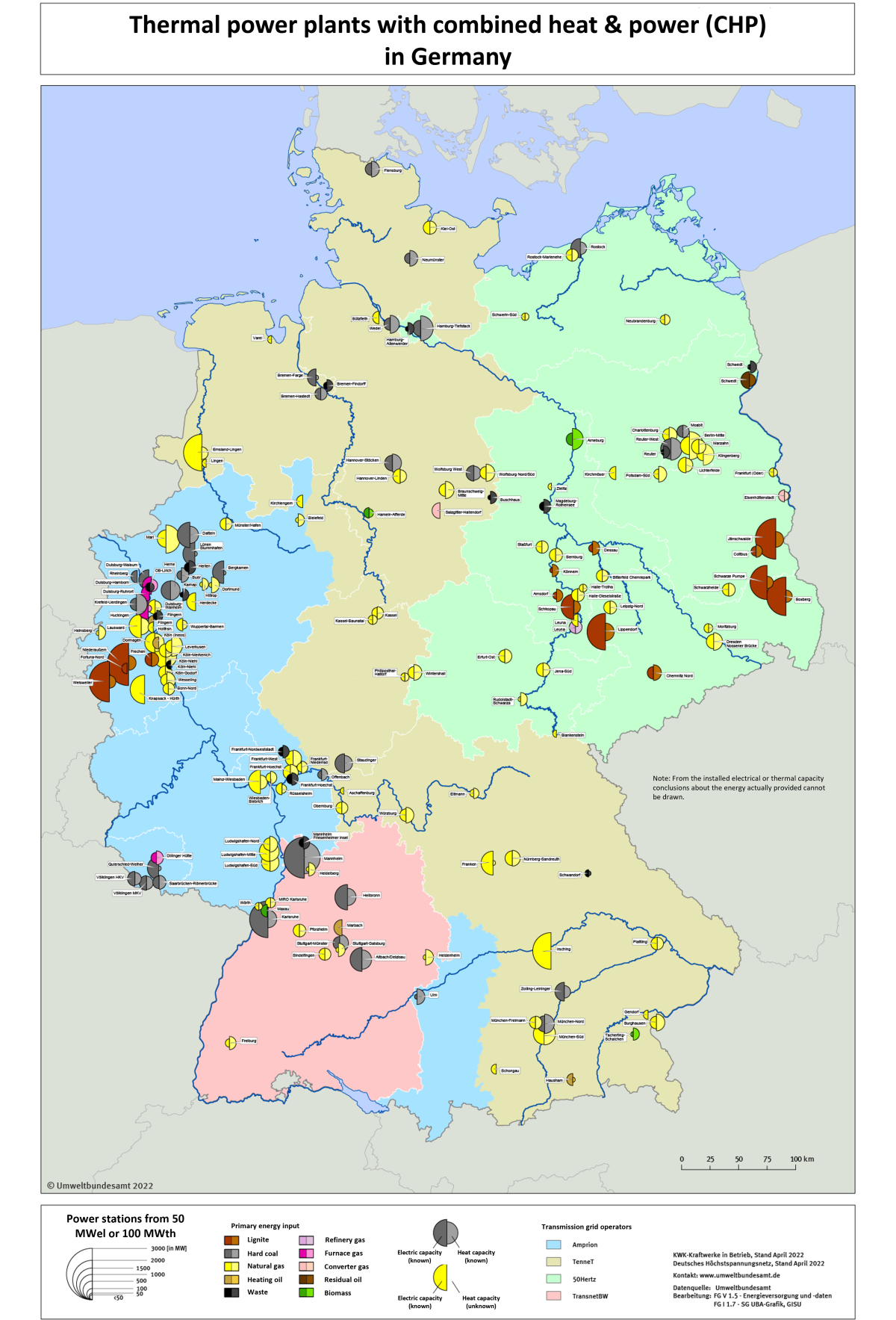

Many of Germany’s fossil-fuel plants generate heat as well as electricity. In 2019, such combined heat and power plants (CHP) provided 113 TWh – or a 19.6 percent share – to the German total net electricity generation of 579.2 TWh.

The majority of the electricity and heat is produced in gas-fired CHP plants. The share of biogas is rising while the share of hard coal, lignite and mineral oil is falling.

Hard coal CHP plants mainly produce heat for public supply (district heating networks) while half of the heat produced by lignite CHP plants is used in the industry sector. Many plants are operated according to the heat demand in the region or by the local industry, and see electricity generation as a by-product.

Until the Russian attack on Ukraine, many operators of coal-fired CHP facilities planned to convert them to gas-fired plants.

In general, hard coal power stations can ramp their energy output up or down more flexibly (although not as flexible as gas-fired plants) while lignite plants tend to be more sluggish.

All this suggests that reducing the use of gas in gas-fired power stations next winter will be a complex undertaking, as many of them are also providing heat for a district heating network of a nearby city or industry. However, where there are still units available that can produce heat and power with coal or lignite, their ramping up can reduce gas usage.

Gas power stations that only produce electricity can generally be more easily replaced by higher generation in other power plants; however, some gas-fired plants in the south of Germany cannot be turned-off entirely as they provide loads and system services that are needed to maintain the grid voltage, the economy and climate minstry said. Therefore, some gas will always be used in power stations for this reason, as well as due to CHP use in industry.

Will CO2 emissions increase because of the renewed use of coal power?

The government has highlighted that the overall cap on power sector emissions under the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) means that emissions will not increase over the limit allowed by the EU’s emission reduction targets, and that the price for emission allowances will increase as demand rises.

The European Commission has proposed using funds from the sale of emission allowances that have been stored in the so-called Market Stability Reserve to get rid of access emission permits that were flooding the market and kept prices for CO2 low, in order to pay for weaning Europe off Russian fossil fuels. Many experts and some member states have opposed this idea, arguing that it would erode trust in the ETS as a climate policy tool.

Think tank Agora Energiewende said in August 2022 that it expects Germany to produce 20 to 30 million tonnes of additional CO2 emissions over the whole year due to more coal-fired power production. This amount is unlikely to make the country miss its emissions reduction target for the energy sector. Its emissions budget for 2022 is 257 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents. Last year, the sector emitted 221 million tonnes.

NGO Greenpeace has demanded that only hard coal plants are used to help in the gas crisis, because lignite plants are far more CO2 intensive. It has also called on the government to detail measures on how excess emissions from the revived coal plants can be saved after 2024. They are estimating an additional 40 million tonnes of CO2 emissions per year.

Will the German coal exit be delayed?

Not according to the government. The measures that allow already mothballed or soon-to-be-shut power stations to come back online to help with the energy crunch over the next two winters are time-limited to the end of April 2024. “The target to complete the coal exit ideally by 2030 remains in place,” the ministry for economy and climate has stated. The legislated end date for coal-fired power in Germany is 2038 at the latest.

Would letting nuclear power stations run longer be a better option than reviving coal plants?

The BMWK is currently preparing a stress test to determine whether nuclear power stations will also be needed to maintain a secure electricity supply in Germany. However, nuclear plants do not produce heat and they are very slow in ramping up and down, thus providing no direct relief for the gas shortage in the heating sector and no great flexibility during times of need. Germany’s remaining nuclear power plants produced about 6 percent of the country’s electricity in the first half of 2022.

Where does Germany source its coal from?

German energy generators source their lignite domestically from the remaining lignite mines which are located close to the power stations and produced some 126.4 million tonnes in 2021. For years, Germany was the world’s biggest producer of lignite, which is the country's most abundant domestic fuel reserve but emits particularly high levels of CO₂.

Hard coal mining – after decades of subsidies – was discontinued in 2018, and since then Germany has had to import all the hard coal it needs. Its leading coal suppliers were Russia (50%), the United States (17%), Australia (13%) and Colombia (6%), followed by Poland, Canada and South Africa (2021 data). The European Union introduced an import embargo on Russian hard coal on 9 April 2022, meaning that no new supply contracts may be entered into as of that date; existing contracts that were agreed before 9 April may be honoured until 10 August 2022. Since the beginning of the year, Germany has reduced its import dependency from 50 to 8 percent, the BMWK states.

What are the difficulties when switching retired coal plants back on?

Some German coal power plant operators have indicated difficulties in finding staff to enable the reactivation of mothballed units. Eastern German lignite plant operator LEAG alone is looking to employ more than 200 specialists on short notice, ranging from machinists to miners and engineers, regional broadcaster RBB reported in early July 2022. Some employees who had previously lost their jobs due to the decommissioning of coal plants have already returned, while LEAG also hopes to re-employ early retirees, the article said. The country’s largest energy company RWE has also halted early retirements.

Another logistical problem are limited rail capacities for transporting more coal from different sources to the power stations, operator STEAG has warned, asking for a priority for coal transports by rail to procure sufficient amounts. Low river levels due to droughts also threaten the supply this year.

Coal plants don’t only emit CO2 but also other health-impeding pollutants such as nitrogen oxide (NOx), sulphur oxides and mercury. LEAG and the state premiers of the eastern German lignite mining states have also stated that some of the lignite units currently in the security reserve don’t meet current emission standards for such pollutants. LEAG has said that since retrofitting them by winter is not possible, these standards must be waived in order to let the plants be operated.

Both the Association of Local Utilities (VKU) and the Association of Energy Intensive Businesses (VIK) have complained that the new government ordinance to let coal power stations re-enter the market doesn’t give operators enough planning security. Since the operating permission is tied to the alert or emergency stages of the national gas supply security plan, permits could end as soon as the alert expires, they fear, and so are asking for a more clearly defined operating time frame.