Energy crunch - How does it affect Germany’s climate policy & what can be done?

You can find the other parts of the series here:

The energy crunch – What causes the rise in energy prices?

The energy crunch – Effects on households and businesses and government's reaction

How do the high energy prices influence Germany’s power mix?

The high prices for natural gas make the German power mix more CO2 intensive – as does less windy weather (2021 was a below-average wind year). Because renewables are the cheapest electricity source, they make up as high a share as possible – depending on weather conditions and sometimes grid capacity – in the power mix. The rest of the power stations follow according to the merit order, i.e. renewables are usually followed by nuclear power and then lignite plants because they can all generate electricity cheaper than hard coal and natural gas plants. In pre-pandemic times, the rise in the CO2 price meant that a fuel switch from hard coal to natural gas was happening more and more often in Germany, as operating coal plants became more expensive (burning coal emits more CO2, hence coal plant operators have to buy more CO2 emission allowances). But despite a considerable rise in the price of CO2 emission allowances under the European Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS), up from around 33 euros per tonne CO2 to almost 90 euros at times, this was more than compensated by the increase in natural gas costs in 2021, so that coal-fired power stations were more in use again, the EWI said. The share of coal power (lignite and hard coal) in the electricity mix stood at 29 percent in 2019, 24 percent in 2020 and 30 percent in 2021.

How do high energy prices influence Germany’s climate and energy policy plans?

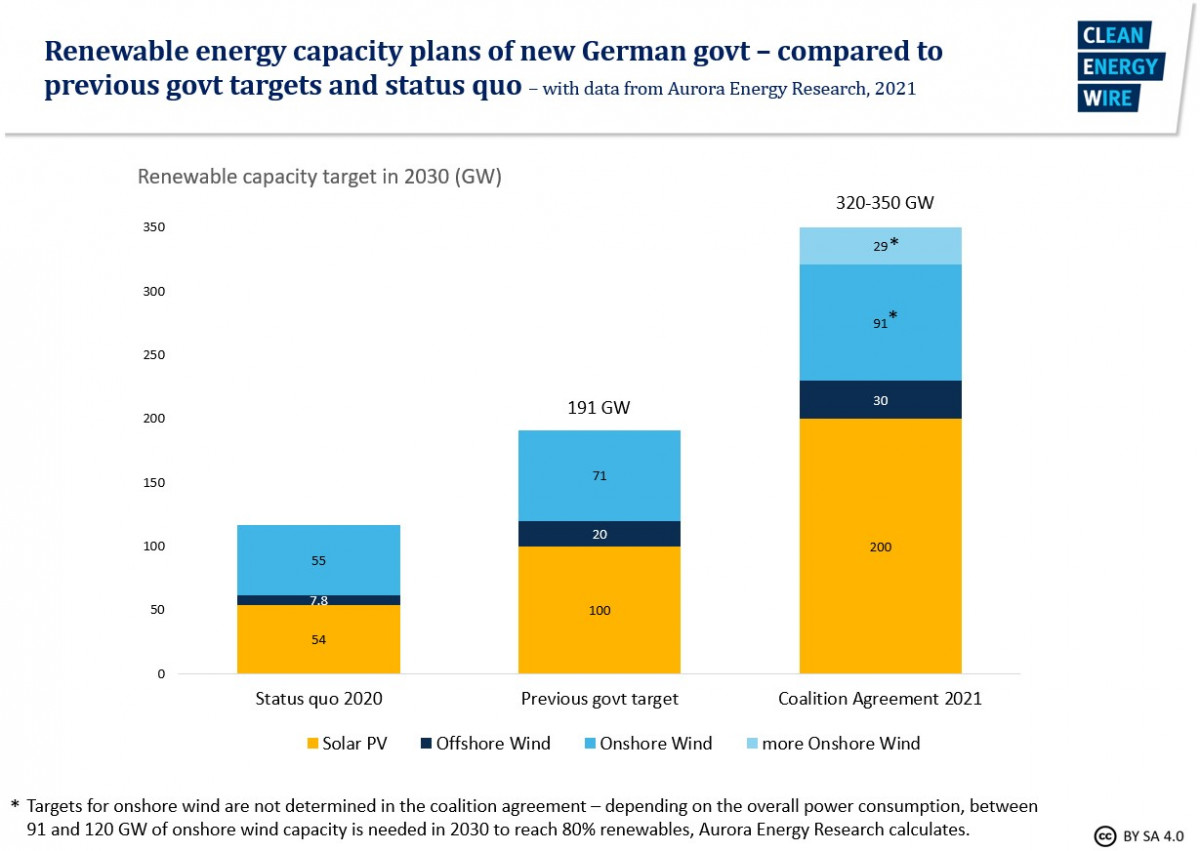

The German government has set itself the ambitious goal of reaching a share of 80 percent renewables in (a rising) power consumption by 2030. Even without the gas and electricity price crisis, there are a number of hurdles standing in the way of reaching these targets, e.g. a slowing onshore and offshore wind expansion; very long and often contested approval procedures both for renewable installations and new power grids; or a growing lack of skilled labour and raw materials. Growth in renewable energy is necessary because all sectors need to be widely electrified to reach the greenhouse gas reduction goal of minus 65 percent by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2045. But to deploy heat pumps, e-cars and hydrogen, clean electricity doesn’t only have to be abundant but also cheap.

The energy crunch is hitting Germany at a time when the government is tightening rules to make the use of fossil energy more expensive (e.g. by introducing a national CO2 price on heating and transport fuels), while starting to make electricity cheaper for consumers by scrapping the renewable energy surcharge on power bills. With prices for both heating and power now skyrocketing, there is a danger that consumers are deterred from clean tech investments, for example by reports that e-car charging prices on motorways have gone up. There is also a danger that government relief schemes and transfers to vulnerable households dampen the carbon pricing signals that the government intends to use to achieve its climate targets.

European governments are under increasing pressure to protect households from sky-high heating and power prices under the region’s unfolding gas crisis, but the resulting relief programmes have the potential to dampen carbon pricing signals and put the bloc's climate targets at risk.

Higher bills also pose the risk that citizens become opposed to higher CO2 prices and other energy transition policies. Economy and climate minister Habeck acknowledged in January that the transition would “deeply affect social reality” and that onshore wind turbines have an acceptance problem. It is therefore vital for the government to show that the energy transition is ultimately a solution for high prices, not an extra burden or the cause of higher bills. Otherwise, come the next election, the three-party coalition with the Green Party at the helm of energy and climate policy could be blamed both for the high energy costs and the failure to reach the climate targets.

What can be done against the energy crunch?

Apart from helping struggling households (see above: “How does the German government react to rising energy costs for consumers”), the German government is pondering other measures that are meant to ensure a secure supply of natural gas this year and in the future.

As a precaution, the economy ministry has plans to establish a so-called digital “solidarity platform” on which gas can be made available to those who need it most at times of scarcity.

Germany has also signed an agreement on solidarity-based gas supplies with Austria, assuring one another of strategic support in the event of a gas supply crisis.

To avoid an actual undersupply of gas (in January, gas storages in Europe were only 50% full – instead of an average of 70% at this time of the year), minister Habeck said that more liquified natural gas (LNG) could be imported. EU LNG ports in the Netherlands, Poland and Italy are only at 30 percent capacity and could potentially substitute pipeline imports to a very large degree.

While there is a chance that the pressure on European gas suppliers could be lifted by more deliveries through the Russian pipelines (as the IEA points out would be easily possible for Russia), there is also the danger that a deterioration of the situation on the Russian-Ukrainian border could curb gas flows to Europe even further. Although very reluctant to speak out openly on the topic, German chancellor Olaf Scholz has suggested that the Nord Stream 2 pipeline would remain closed if Russia invaded Ukraine. If Scholz were to play this card, gas imports from Russia would likely diminish even further.

Both government officials and RWE CEO Markus Krebber have stressed that there is no danger of Germany running out of gas and “radiators staying cold tomorrow.”

With a view to avoiding a similar gas crisis next year, the government could implement a strategic gas reserve (Germany has a state-regulated oil reserve but not a gas reserve) e.g. by obliging suppliers to physically store gas for their contracted customers so that an undersupply is prevented in the event of a supplier’s insolvency, Sebastian Bleschke, managing director of the association of natural gas storage operators (INES) in Germany, suggests.

In the long term, the best option for Germany and Europe is to replace coal and gas power generation with renewables as quickly as possible, energy experts, such as Christoph Podewils or Uniper CEO Maubach, say.

This is reflected in the new government’s major push for more renewable capacity as fast as possible. The economy and climate ministry has announced that it will increase tender volumes for wind and solar power and the minister has started to tour the federal states to gather support for the coalition’s plan to have two percent of Germany’s land surface used for onshore wind generation. In a few months’ time, a change in distance rules from radio beacons and military areas could free up land where wind turbines have otherwise been approved amounting to nine gigawatts of additional wind capacity. All of this will not provide a solution for the current gas shortage-induced turbulence but it will make Germany’s energy system more climate-friendly and more future-proof in the longer term.

The government also plans an overhaul of the power market design but hasn’t specified any details yet. In a first input paper, researchers have pointed out that a fundamental reform of the system of taxes, charges and levies on energy prices is necessary. Other experts have said that the future power market design and renewables financing have to function differently (e.g. through contracts for difference or by obliging renewable energy operators to repay windfall profits due to the merit order).

The IEA warns that dependence on natural gas will remain an issue in Europe in the foreseeable future and that the entire world is in need of more clean energy investment to ward off reoccurring market turmoil. “[Clean energy investment] would need to triple by 2030 to get the world on track for a pathway consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5 °C,” the IEA writes. It also names energy efficiency gains as a powerful tool for governments, businesses and consumers to reduce exposure to fuel market volatility and says that European governments should improve regulations to better scrutinise gas storage levels and obligations.

What role does Germany’s import dependency on Russian gas play?

About 17 percent of Germany's electricity were provided by gas in the first half of 2021. As part of its strategy to become climate-neutral by 2045, the country is planning to use natural gas as a bridging technology, while it phases out nuclear power and more climate damaging coal. While this will eventually make it independent from Russian fossil fuel imports, the government says that even more flexible gas plants will be needed by the end of the decade even if they can be switched to hydrogen use later. The same is true for other European countries, which are replacing coal with fluctuating renewables and gas, and which also have rising power demands. Industry association BDI says that the dependency on imports is not a valid argument against new gas plants. “ Germany is and will remain an importing country for energy, even if the energy sources will be CO2-neutral in the long term,” BDI president Siegfried Russwurm said in January 2022.

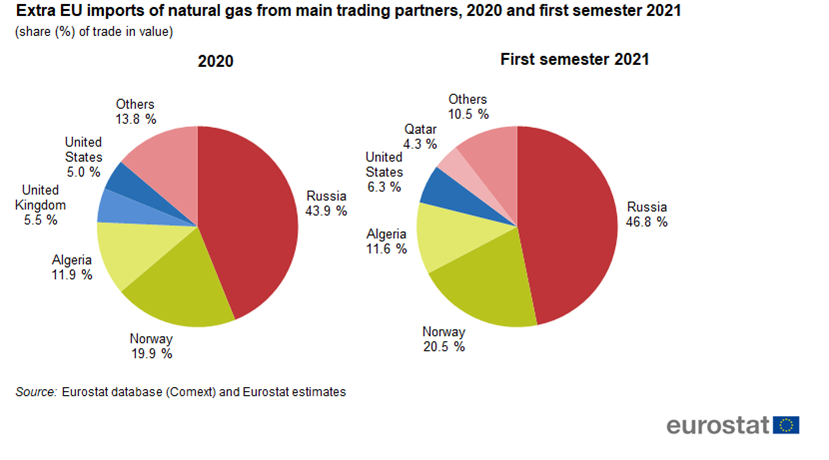

Germany is among the world’s biggest natural gas importers and around 94 percent of its gas consumption is met by imports, according to the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR). The EU receives over 40 percent of its natural gas imports from Russia; Germany between 50 and 75 percent.

“Europe finds itself in a perfect storm of its own making. It faces a gas price and supply crisis that makes it vulnerable to political blackmail [by Russia],” writes Constanze Stelzenmüller, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe. She argues that while intending to make energy supply climate friendly and ensure a just transition, Europe has dropped the ball on energy security by too heavily relying on natural gas from Russia.

It must be noted, though, that the current turbulence is an almost-global (with the notable exception of the U.S.) gas price crisis that isn’t limited to the EU or to countries directly dependent on Russian imports. The UK, for example, is struggling with the same price spikes, although it only receives around five percent of its natural gas from Russia. Its problems arise instead from comparatively small storage facilities and from sourcing around one-third of its gas needs from Qatar or the U.S. via LNG deliveries. These are particularly sensitive to global wholesale prices, meaning that during the global increase in demand towards the end of the pandemic (especially from China) high prices hit the country as badly as the rest of the continent.

Nevertheless, it is obviously advisable to diversify gas imports, the German government acknowledges. Norway (Germany’s second biggest source after Russia) cannot increase deliveries, prime minister Jonas Gahr Store said in January 2022. Supplies from the Netherlands, Germany’s third largest provider, are getting less as output from Dutch gas wells in the North Sea is falling.

During the time of the Trump administration, which pushed Germany to abandon the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and embrace LNG deliveries from the U.S., the Merkel government in 2018 made an attempt “as a gesture to our American friends” to help with the construction of LNG landing terminals. However, they also kept to the line that new investment decisions for natural gas trade are “generally” left to private market actors, and four years later, not one of the envisaged three terminals have started construction.