What are the climate and energy plans of German election winner Scholz?

To the surprise of many observers, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) under their chancellor candidate Scholz have managed to become the strongest party in Germany’s 2021 elections. Election winner Scholz has made clear that he intends to form coalition government with the Green Party and the pro-business FDP. But finding common ground on Germany’s future climate and energy policy will likely play a decisive role in whether this endeavour proves successful. While the SPD's election programme puts great emphasis on halting global warming as the "challenge of the century," the top candidate has not yet gained himself a reputation in energy and climate policy.

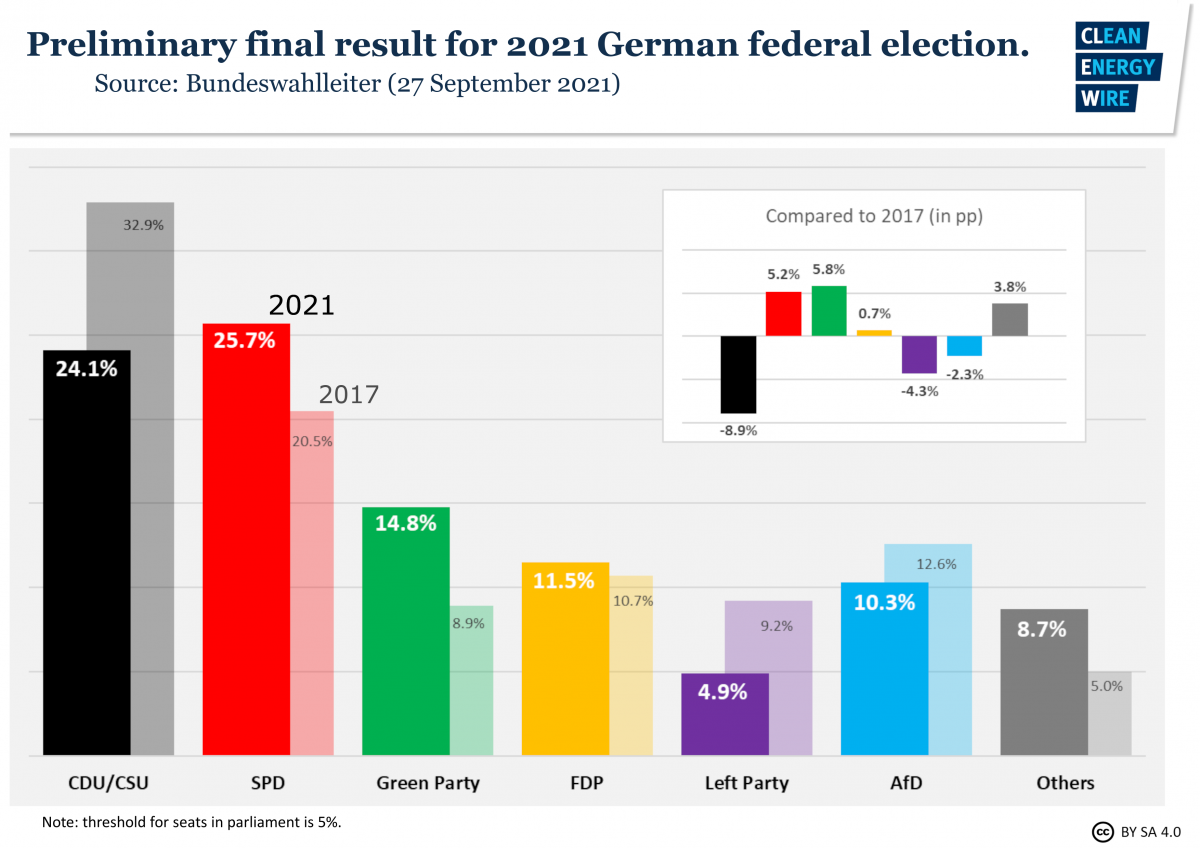

After a successful sprint to the finish that put an end to several years of declining poll ratings for the country’s oldest party only weeks before the vote, the SPD beat the conservative CDU/CSU alliance under candidate Armin Laschet with 26 against 24 percent in a narrow election victory that will now likely bring Germany its first three-party coalition. Although the conservatives have not yet relinquished the idea that they too could form a government coalition with the Green Party and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP), Scholz’s claim to the chancellery in a coalition with the same two parties receives much more backing across political camps and among voters. Serving as finance minister and vice chancellor under conservative Angela Merkel’s last government, Scholz successfully ran a campaign that at the same time promised continuity with Merkel’s still widely popular style of consensual government and a slight change in tone with a greater emphasis on questions of social justice and workers’ rights.

The SPD has significantly shaped Germany’s overall energy policy in the past two decades, being either a senior or junior partner in five out of the six last governments since 1998, and introduced or at least backed most of the climate and energy legislation of the outgoing administration. This includes policies like Germany’s Climate Action Law, the coal phase-out or reforms to the Renewable Energy Act (EEG). But the SPD and Scholz have repeatedly stressed that Merkel’s conservatives often prevented more ambitious policies and vowed to enact quick overhauls that set the country on a path towards its 2045 climate neutrality goal immediately after a new government is formed.

Those who simply keep turning the fuel price screw show how little they care about the hardships of the citizens

Researchers and observers agree that the country will have to quickly implement a wide range of measures that underpin the ambition to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045, many of which are likely to pose tough challenges in terms of voter acceptance and social cohesion. An SPD-led government with the Greens and the FDP would have to bridge diverging interests ranging from fossil or car industry workers fearing to lose out in the energy transition over hundreds of thousands of climate protesters to small and medium-sized companies worried about the short-term costs to business that rapid decarbonisation might entail.

SPD's promise to shield voters from climate costs could put brakes on CO2 price

Scholz, who already served as employment minister under Merkel from 2007 to 2009, has run a campaign focussed on the interests of low-wage earners, tenants and a general idea of more “respect” towards the economic and social struggles of citizens, in which climate policy was often mentioned in the same breath as social justice. Even though Scholz said he wants to become a “climate chancellor,” this will likely set the SPD limits in terms of what they will want to demand from voters financially to contribute to emissions reduction. This is all the more the case, because the party’s leaders, Norbert Walter-Borjans and Saskia Esken, are considered party left-wingers, and beat Scholz in an internal contest for the SPD leadership in 2019.

The candidate himself is considered to be a more centrist-leaning pragmatist, who also has an open ear to employers and high finance but has been wary to avoid the impression that he ignores the plight of the less well-off in the energy transition. In July this year, Scholz said “there won’t have to be any major sacrifices” for protecting the climate, suggesting that high-wage earners had a bigger lever to pull than others when it comes to emissions reduction. SPD energy politician Johann Saathoff backed his party’s cautious approach to higher climate costs in an interview with Clean Energy Wire, saying people who already feel the impact of carbon pricing in transport and heating introduced only in 2021 would need support to adapt.

While Scholz is for a Europe-wide expansion of Germany’s national carbon price in transport and heating similar to the existing EU emission trading system (ETS) for industry emissions, he has been reluctant to back a national price in the first place and sceptical of drastic price increases once the CO2 price had been introduced. “Those who simply keep turning the fuel price screw show how little they care about the hardships of the citizens,” Scholz said in June 2021, criticising a proposal by the Greens to increase it.

Scholz's faster renewables expansion promise requires modernisation of German administration - energy lawyer

Scholz has made faster renewables expansion his key climate policy ambition in the short term, should he become leader of a new government. His key message was: Focus on renewables expansion because otherwise there will not be enough clean electricity for all other decarbonisation plans, from e-mobility to heating, green hydrogen production and infrastructure modernisation. "The most important task for the new government right at the start of the next legislative period will be to increase renewables targets and enable faster approvals and grid extensions,” Scholz said during his campaign. In its election programme, the SPD demands 100 percent renewable electricity by 2040, solar installations on all suitable roofs, every supermarket, every townhall, every school and a “pact for the future” with states and local authorities that gives them binding renewable targets.

To ensure that these plans come to fruition, Scholz has promised a new law that is meant to guarantee that industry has enough renewable electricity to decarbonise in the coming decades. Earlier this year, Scholz had ridiculed the conservative-led energy ministry for not acknowledging that Germany will need much more electricity in the future than previously planned and that renewable capacity targets should be adjusted accordingly. Scholz promised an “immediate fresh start” in climate and energy policy, saying that "as chancellor, I will ensure we pick up speed in the first year," adding that he plans to accelerate approval procedures for wind turbines and other investments.

Lagging onshore wind power expansion is currently seen as the greatest obstacle to a faster renewables roll-out in the country. The technology already covers about a quarter of Germany’s annual electricity consumption and is also supposed to be the biggest pillar in the future power mix. But its expansion is also one of the sour points of Germany’s energy transition, as local opposition to new wind parks, restrictive rules in many states as to where turbines may be built and drawn-out planning procedures have caused wind capacity additions to almost come to a halt since 2017. "We have to speed up the approval and participation procedures [for wind power installations]," Scholz has said. The approval of a wind turbine should not take "six years, but must succeed in six months," he said during the election campaign.

But Scholz’s central idea of simply streamlining planning procedures and especially cutting back citizen participation could become difficult, energy lawyer Miriam Vollmer told Clean Energy Wire. The current law already has deadlines that keep approval procedures to under seven months. But the cases where difficulties arise because of species protection or noise pollution are the ones taking much longer due to courts commanding a halt to construction, she said. “When it comes to stakeholder participation and environmental organisations’ rights to legal action, these are mandatory in Germany under EU law and cannot be abolished by the federal legislator,” she explained. The best way to really speed up planning procedures would be to better staff and equip the administration and courts, Vollmer said, adding that “with the FDP as a party that takes digitalisation seriously and the SPD that is backed strongly by people in public administration, a coalition of the SPD, the Greens and the FDP should have a realistic chance to modernise the administration.”

Earlier coal exit? Scholz "would like to make it happen"

With respect to the climate policy topic that dominated the previous elections, Germany’s coal phase-out, Scholz sent out mixed messages whether he would like to bring forward the final exit date from the current target year 2038. Speaking to coal workers in the eastern mining region of Lusatia during an election campaign event in August, the Social Democrat said the country should stick to its phase-out schedule. "We have made clear agreements that are important for the companies, for the workers and also for the region. And these agreements apply and should be respected,” he stated, only to qualify this promise a few days later in a debate with other chancellor candidates. “We have regular evaluations that allow an earlier phase-out, so 2038 is just the last possible year," he argued, adding that he would like to “make it happen” that coal-fired power production is ended earlier. For him, the question of ending coal is closely linked to the challenge of setting up a viable alternative by ramping up renewable power both in Germany and internationally. “Hundreds of new coal-fired power plants are planned worldwide. They will not be put into operation only if there is a better alternative,” he argued.

SPD candidate confident carmakerswill stop betting on fossil-fuelled cars all by themselves

Regarding the pressing but highly controversial challenge of emissions reduction in the transport sector, Scholz argued that a ban on combustion engines for new passenger cars in Germany is not necessary, as carmakers would stop betting on fossil-fuelled cars all by themselves in the near future. At the same time, he said the car companies do not need generous government support to achieve the transition to electric engines. “The car companies can invest tens of billions on their own – and they are doing so,” he argued, adding that smaller supplier companies might well need some state investments to weather the shift to electric cars. The SPD candidate also opposed the idea suggested by the Greens that road infrastructure should not be expanded further, arguing that the new e-cars “need good roads” as well. The “long-term” aim of moving more passenger and freight traffic away from the roads to railway would take much longer than some are hoping, Scholz argued, which is why Germany could not afford to neglect road infrastructure.

Sustainable finance and an international "climate club"

In other areas relevant for Germany’s climate policy, Scholz has used his position as finance minister since 2018 to oversee the creation of a national sustainable finance strategy, meant to better align the financial sector with the emissions reduction goals and dry up the funding of climate-damaging activities. While the strategy still hinges on the finalisation of an EU-wide sustainable finance taxonomy and has left critics dissatisfied with certain aspects, it was widely welcomed as an overdue filling of a gap in climate policy.

With a view to international cooperation on climate action, Scholz made inroads by proposing a “climate club” bringing together the most ambitious countries in of the field of emissions reduction. His initiative would at the same time oblige companies in these countries to comply with climate protection requirements but also seek to protect national economies from the disadvantages of international competition. The economic cooperation proposal launched by Scholz underlined his general idea of how Germany should approach climate action in the tough years that lie ahead: "For the SPD, climate protection is an industrial project, not a re-education course.”