Climate policy rift promises thorny talks between German election ‘kingmakers’ Greens and FDP

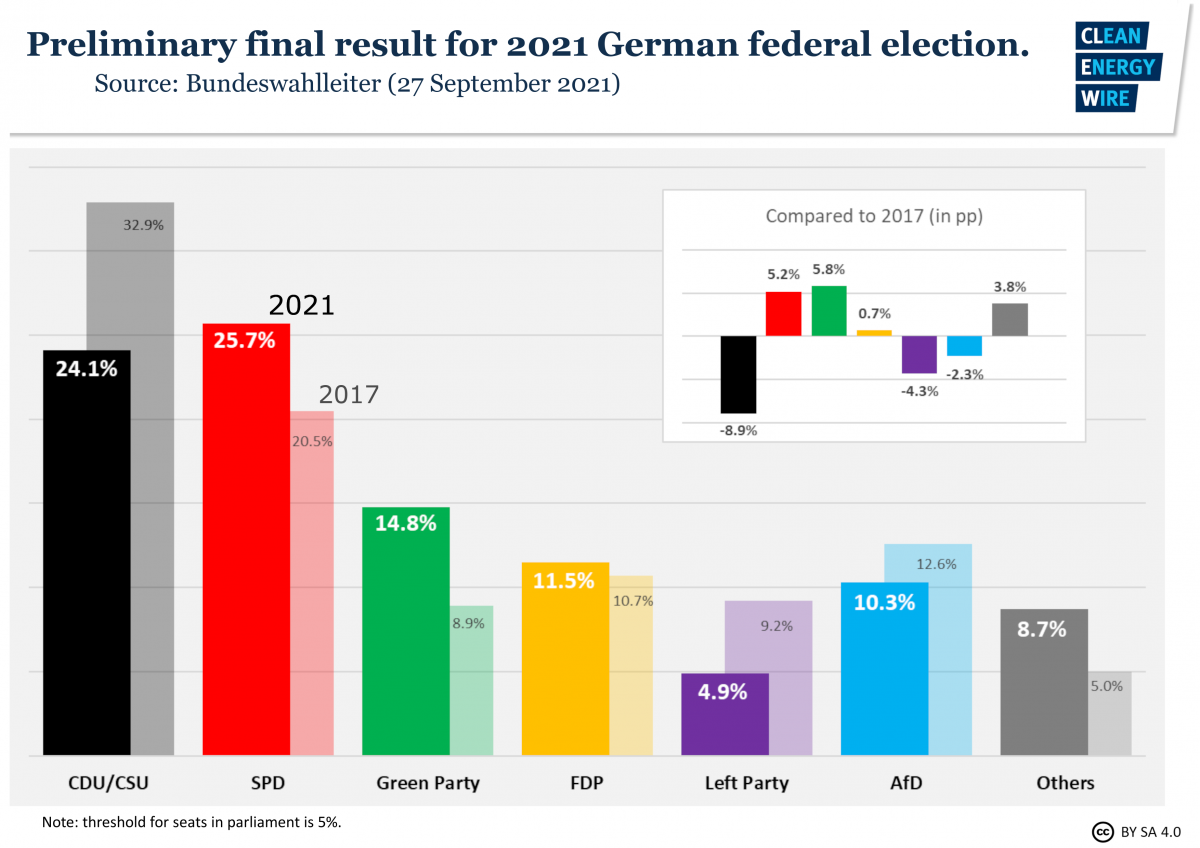

Germany looks set to get a three-party government coalition after an election that handed the Social Democrats (SPD) a thin victory over the conservative CDU/CSU alliance. The Green Party and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP), who came in third and fourth, respectively, look set to become "kingmakers" for a new government either under the leadership of SPD chancellor candidate Olaf Scholz or his conservative rival Armin Laschet. The two smaller parties’ leaders, Annalena Baerbock and Christian Lindner, immediately signalled they would first sound out the potential for cooperation among themselves before entering into talks with either of the two bigger parties. Almost all parties explicitly stated after the election that more ambitious climate policies will be their key aim if they become part of a new government. But deep rifts in the two smaller parties' exact plans to fight climate change indicate that finding an agreement between the next government’s junior partners will be difficult.

“We will start with talks between the FDP and the Greens,” Green Party parliamentary group leader Anton Hofreiter told public broadcaster ARD. “We will see what we have in common.“ He said that the SPD has a much clearer claim to lead the next government than the conservatives. The SPD already said it would seek quick coalition talks with both parties, whereas the CDU/CSU appeared much less unanimous regarding the further course of action, following its worst-ever election result. “The conservatives have lost, the SPD has won,” Hofreiter argued. He stressed that his party would aim for the “maximum achievable” in its quest for a more ambitious climate policy in the upcoming talks. The next coalition must not only try to find “the lowest common denominator,” but achieve the Paris Climate Agreement’s targets, Hofreiter said.

FDP leader Lindner said his party would talk to the Greens first because this is where the greatest differences among the four largest parties are, adding that climate policy is a good example for their diverging approaches. While the FDP followed “a technologically-driven model,” the Greens would make climate action “a lifestyle question,” Lindner said. Given these differences, it would be reasonable “to look for common ground” first. However, Lindner also cautioned that forming a coalition with the SPD might become difficult for his party given the Social Democrats’ influential left-wing faction under party leaders Norbert Walter-Borjans and Saskia Esken. However, the FDP’s parliamentary group said it would attempt to quickly initiate talks with the other parties, with the aim of fully getting started by the end of this week.

"Traffic light" or "Jamaica" coalition?

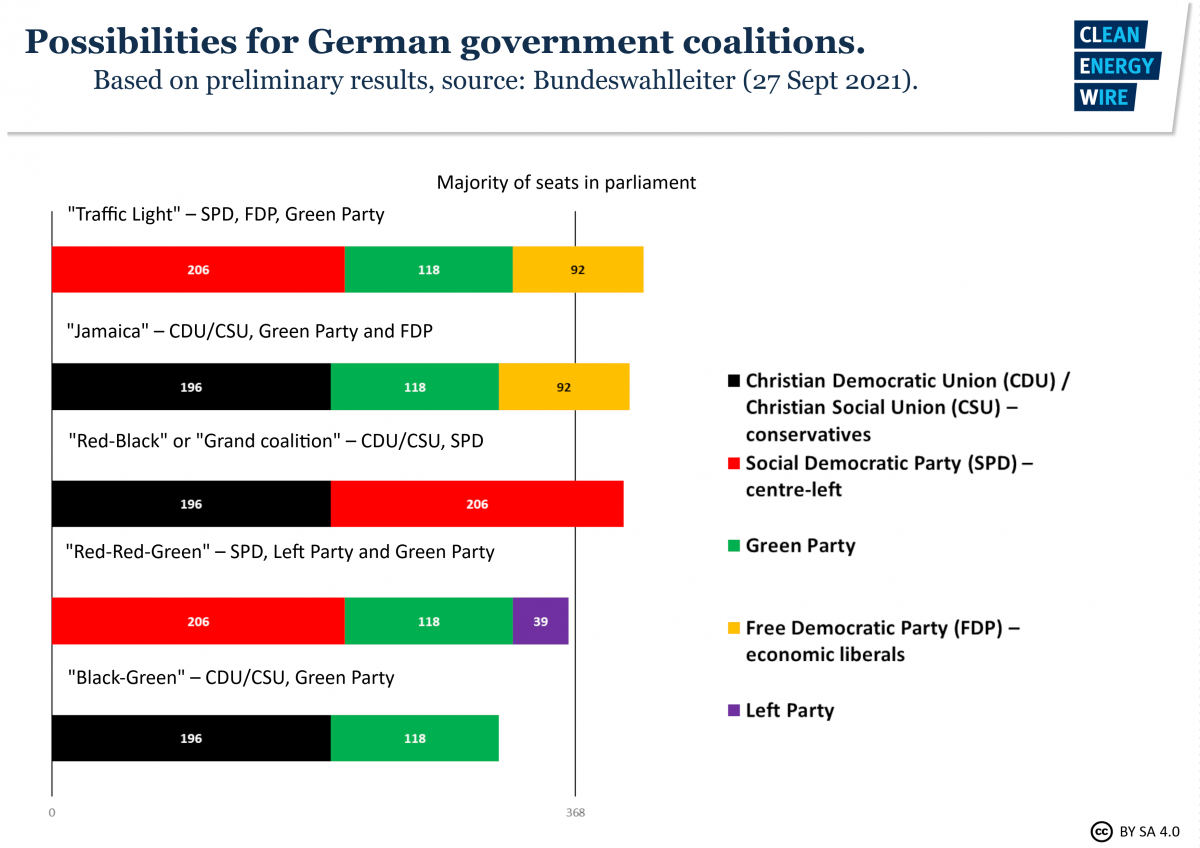

The most likely coalition options include both the FDP and the Greens, with either the SPD or the conservatives as the senior partner. The so-called ‘traffic light coalition,’ based on the parties’ colours, would see the SPD get together with the Greens and the FDP. A ‘Jamaica coalition,’ on the other hand, would see the CDU/CSU take the leading role. This alliance was already attempted in 2017, but the FDP decided to walk away after weeks of talks, with party leader Lindner arguing at the time that it would be “better to not govern at all than to govern wrongly.” The current "grand coalition" between the conservatives and the Social Democrats would also hold a majority in parliament – though with switched roles, as the SPD now becomes the larger faction. But the two-party coalition that has governed Germany for 12 out of the past 16 years has become widely unpopular both among voters and the parties themselves, making a renewal unlikely.

For political analyst Arne Jungjohann, both a traffic light coalition and a Jamaica coalitionare conceivable options. “There is no playbook for this situation for the parties,” he said, adding that the election result amounted to a “political earthquake” that marked “a turning point” in German politics. The Green Party-affiliated analyst said he expected tough exploratory and coalition negotiations in the weeks and possibly months ahead. “To join a coalition, each party will have to credibly demonstrate towards its supporters that such a coalition would deliver its specific goals,” he said. Although setting up a new government might not take as long as after the 2017 elections, when the grand coalition was renewed six months after the vote, deciding on a new chancellor could still become a lengthy procedure, Jungjohann argued.

Combustion engine car phase-out a bone of contention

Climate and energy policy could emerge as a major stumbling block in the upcoming negotiations – especially in the talks between the Greens and the FDP. All leading parties made it clear after the vote that a comprehensive reform of Germany’s climate policy would have to be a cornerstone of the next government, but the approaches to turning ambition into action vary widely.

The Greens have run a climate policy campaign that includes several regulatory changes to curb the use of climate-damaging technologies. This includes an earlier end to coal-fired power production, an end date for the sale of combustion engine cars or a speed limit on motorways, a goal shared with the SPD. At the same time, the Greens favour large-scale investment programmes to boost more climate-friendly technologies, potentially financed with government debt or higher taxes. This directly clashes with the FDP’s key election promise not to raise taxes and generally exert fiscal discipline by not creating new public debt. At the same time, the FDP is strictly opposed to prohibitive rules and bans on specific technologies, advocating a market-based approach instead centred on carbon pricing.

According to an analysis of the different coalitions’ cohesion in climate policy conducted by consultancy DWR Eco, the Greens and the FDP could possibly find common ground in quickly doing away with subsidies for fossil fuels and on a concept for expanding the European Emissions Trading System (ETS) to more sectors of the economy. Both parties are also unlikely to block the end of renewables funding through the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) but differ on what should replace it.

Like most other parties, the Free Democrats and the Green Party also agree that the expansion of charging infrastructure for electric mobility should be accelerated with state assistance. Another possible stumbling block could be the use of hydrogen and other alternative fuels in transport, which the Greens oppose as they prefer to clearly focus on battery-electric cars, but the FDP backs due to its general emphasis on remaining “technology-open,” instead of ruling out possible emissions reduction instruments, such as combustion engines with climate-neutral fuels.

The Greens and the Free Democrats would both want to increase investments in energy research, but the Greens favour funding that should go into cleaner infrastructure and industry facilities. The FDP wants less direct intervention and more market forces to direct investment flows.

The Greens are the only party advocating a direct increase of Germany’s CO2 price from the current 25 euros per tonne to a minimum of 60 euros by 2023 for installations regulated under the ETS. The FDP opposes a fixed price and wants a strict CO2 budget in the ETS instead, which would then allow for free pricing. The SPD is opposed to quick price rises due to social considerations, while the conservatives are more open to increasing the CO2 price. All parties agree that there must be a financial compensation mechanism for citizens.

An earlier coal exit, preferably no later than 2030, is a priority for the Greens and the FDP could live with it provided that it is market-driven. The earliest possible date mentioned by SPD candidate Scholz is 2034. The conservatives have also said that ending coal in 2038 as agreed in the coal exit law is unlikely.