Tumultuous first year for Germany's government may start energy transition push

When Germany’s “traffic light coalition” took office in early December 2021, it promised to make energy and climate policy central to its work. The three-party coalition under chancellor Olaf Scholz vowed to deliver a new style of government after 16 years of Angela Merkel’s leadership by making climate and energy a thread that runs through all of their policies; from healthcare to finances to foreign policy. One year later, energy policy indeed has been at the heart of the German government’s agenda – although under vastly different circumstances than it had initially hoped for.

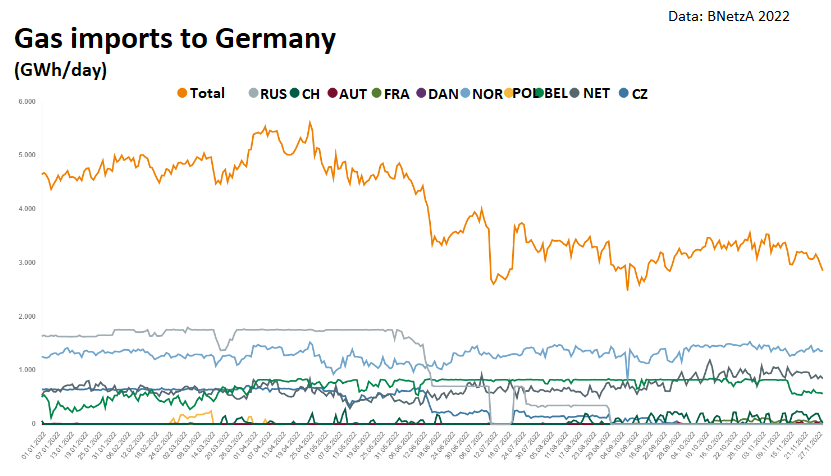

Russia’s attack on Ukraine that was launched soon after the government's inauguration on 8 December last year and the ensuing energy crisis in Europe sent the traffic light coalition -- named after the party colours of Scholz’s Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and the Free Democrats (FDP) -- through a baptism of fire. The crisis made some of the goals of the coalition treaty difficult to achieve, but greatly accelerated the progress of others. While many observers initially deemed the government’s reaction constrained and reluctant, it ultimately took a big step towards readjusting the country's energy policy and sped up the process of cutting the vast direct dependence on Russian energy.

The “Zeitenwende” watershed moment Scholz announced just days after Russia launched its invasion attempt inevitably came with substantial political costs for the new government. On the one hand, it had to prepare voters and businesses which had just emerged from two years of the pandemic for another nationwide crisis due to skyrocketing energy prices threatening the country’s industrial core and social cohesion. On the other hand, Germany’s standing among its European neighbours was shaken as the country -- despite many and repeated warnings by its allies against deepening ties through the unused Nord Stream 2 pipeline -- found itself exposed and vulnerable to Russia’s weaponising of energy assets, thereby weakening the EU’s position as a whole. Furthermore, chancellor Scholz’s SPD played a central role in the political miscalculations preceding the crisis. Even the EU's key axis of French-German cooperation appeared to suffer from the energy crisis's fallout, an impression both governments sought to counter by demonstrating their readiness for finding joint answers.

Yet, in the first twelve months in office Scholz’s administration also accomplished several energy policy breakthroughs in its crisis response that a year earlier appeared elusive or even unthinkable. Despite losing its primary gas corridor, Nord Stream 1, after Russia turned off the tap in August, the country’s gas storages were filled 100 percent ahead of schedule. An attack that blew up the pipeline under the Baltic Sea in late September then made a recourse to the supply route all but impossible. Aside from the government rapidly securing new import venues and solidarity agreements with Germany’s neighbours for natural gas, this had been made possible by businesses and households heeding government calls to reduce consumption. A rapid ramp-up of import infrastructure for liquefied natural gas (LNG), largely thought to be a dead duck when the traffic light coalition took over, have been pursued since February to further bolster long-term supply by 2023. The first floating import terminal could receive deliveries as early as December or January of next year.

Comeback of coal and extension for nuclear power a hard sell for Green voters

To secure the energy system from possible gas and electricity shortages in the interim, several coal-fired power plants have been brought back to supplement the country’s power system and replace gas-fired units. The decision to bring back coal has been a hard sell to members of the Green Party, but nevertheless was carried out swiftly after the war’s outbreak. Economy and climate minister Robert Habeck from the Green Party sought to calm critics of the coal return by striking a deal with western coal state North Rhine-Westphalia and energy company RWE. The idea was to stick to the 2030 end date for fossil fuel consumption in the state despite temporarily bringing capacity back online – a compromise that appears to be more difficult to achieve with eastern regions.

Another turnaround that unsettled the Green Party was the runtime extension for Germany’s remaining three nuclear plants, which took the government much longer to decide. It required chancellor Scholz to put his foot down to end a months-long dispute between Habeck and finance minister Christian Lindner, who had led calls for a long-term return to nuclear power. The plants will now get a three-month extension until April 2023 before going offline for good.

In his role as treasurer, Lindner, who as head of the pro-business FPD has often condemned high public spending, oversaw the launch of four major aid programmes to help citizens and companies deal with high energy prices, including a 200 billion euro “defence shield” that includes caps for consumer prices of gas and electricity. While this has failed to ease fears that households could be in for a rude awakening when greatly increased energy bills land in their mailboxes next year, the measures helped calm markets and provided reassurances that the government would commit to addressing social hardships and preserving the country’s economic foundations. This challenge would continue to dominate political debates in 2023, when the country is expected to enter into a recession, Habeck said.

While providing support to struggling citizens and businesses without creating incentives to use more fossil fuels has posed many technical challenges for the involved ministries, the trade union-affiliated Hans Böckler Foundation called the measures “socially balanced.” However, industry representatives were less satisfied, particularly in regards to support payments for struggling gas importers. Economy minister Habeck’s reputation, which had grown during his first months in the role, took a hit when his plans to fund a special gas levy that would have further increased prices fell flat in a last-minute decision in early autumn. Companies like Uniper, the country’s largest gas importer, had to be put under state control to avoid a collapse of the import infrastructure.

To counter the possibility of de-industrialisation and economic decline as a result of high energy prices and industry transformation, the energy transition and Germany’s quest for climate neutrality by 2045 have emerged as the traffic light coalition’s main trump card. At the presentation of the coalition treaty, Scholz announced that by ramping up climate-friendly technologies and leaving fossil fuels behind, his government would launch “the biggest industrial modernisation project in more than 100 years.” This goal has been amplified by the urgency to use renewables to bring down energy prices and become more independent in supply.

Ambitious renewable power package's effects likely to become visible only in next years

There is optimism that this change in circumstances could ultimately benefit the entire project, illustrated by finance minister Lindner's relabelling of renewables as “freedom energies” that serve a purpose beyond fighting climate change. At the same time, years of fierce debate over the cost of renewable power integration -- compared to seemingly less expensive fossil fuels -- were to a large degree silenced by the enormous toll European economies are now paying to cushion the worst effects of the energy crisis. Egged on by government support programmes for efficiency measures, citizens also responded by adapting their equipment and behaviour, sometimes even exceeding the government’s expectations. Installations of heat pumps and applications for energy-efficient building modernisation reached record levels in 2022 as customers sought to shield themselves from future fossil fuel price hikes or even supply cuts.

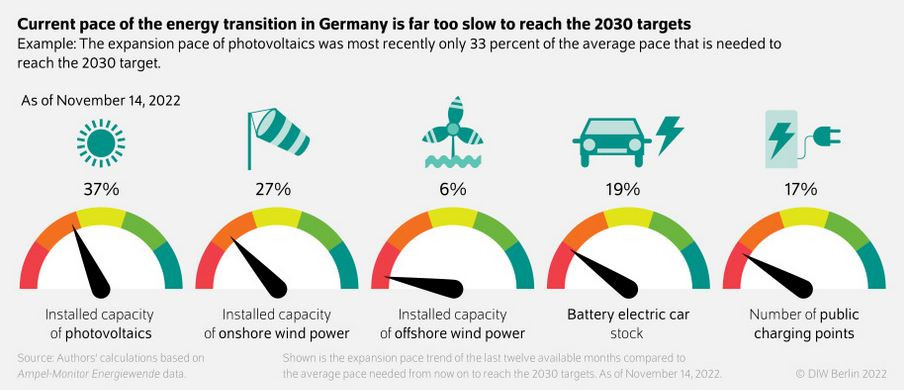

However, the central task to expand Germany’s renewable power capacity – as well as complementary grid and storage infrastructure – remains the biggest challenge Scholz’s government must tackle to meet its green transformation targets. Virtually all decarbonisation efforts, from heating to industry and transportation, hinge on renewable power to electrify sectors and produce green hydrogen. With what it called Germany’s “biggest energy policy reform in decades,” the coalition’s “Easter Package” introduced in spring 2022 aimed to get a breakthrough in pushing the energy transition forward and elevating the rollout of wind and solar power “to a completely new level.” With the help of this package and other legislative changes, the government wants to double the country’s onshore wind capacity to 115 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, more than triple offshore wind capacity and add over 20 GW of solar PV installations annually to reach a total of 215 GW by the end of the decade.

When announcing these policy reforms, the economy and climate ministry cautiously added that any “physical” differences against which the government’s performance could be measured will only start to reveal itself within the following three years until 2025. According to economic research institute DIW, the pace of the energy transition still falls short in many areas. In order to reach the 2030 targets, “growth must pick up very strongly in the next few years,” it concluded.

Several obstacles still stand in the way of reaching a new level of clean power production, among which a major lack of more than 200,000 skilled workers and persistent bureaucratic hurdles dampen the prospects for a timely roll-out. While the government has sought to tackle worker shortages, economy minister Habeck insists that the red tape which prevents the building of renewable power infrastructure to a large extent stems from state regulation. Implementing construction after the federal government provides legal groundwork particularly for wind power would then be a task for the country’s 16 state governments, the Green minister insisted.

Party rivalries a looming risk for coalition's cohesion

Voter response to the traffic light coalition has been mixed, reflecting the turmoil the new administration found itself in. Each of the three parties had to accept difficult decisions following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some of which they likely would not have had put up with without a war in Europe. A survey released in November revealed that merely 15 percent of respondents thought the coalition stands for climate action and sustainability -- a disappointing result especially for the Green Party, which is reflected in the increasingly problematic relationship they have with climate protesters who use acts of civil disobedience to further their cause. Yet, the Greens are the only party that was able to improve its standing in the polls following last year’s election throughout their first year in government.

Scholz’s SPD lost the top position in aggregated polls to the conservative alliance under CDU leader Friedrich Merz and the traffic light coalition no longer has a majority in polls just one year after it was established. The party’s leading role in expanding energy trading with Russia in the past 20 years and Scholz’s initial hesitance to clearly communicate his support for resisting Russia's aggression cost him and the SPD voter confidence – although according to another poll by public broadcaster ZDF, more than half of voters say the chancellor is doing a good job.

Popularity is sliding for Lindner’s pro-business FDP, who had been most wary of the partnership with the two more left-leaning coalition partners. Having lost the most voter approval both in relative and absolute terms, they are also the coalition party who had the biggest losses in the four state elections that took place in 2022. Doubts could be spurred within the party about its benefits from the arrangement. After his party failed to enter parliament in the election in the large northern state of Lower Saxony, FDP head Lindner suggested the whole traffic light coalition had “lost legitimacy.”

The judgement of SPD co-leader Lars Klingbeil, meanwhile, is less pessimistic. In an interview with tabloid Bild, he said the traffic light coalition’s performance after one year with multiple crises ranging from “Putin’s war, the energy crisis, inflation and the climate” could be rated as “satisfying,” given the circumstances. Klingbeil urged the coalition to engage in less public disputes and stop debating which one has enforced their interests best. The government should instead “go back to the political culture of our coalition negotiations,” the SPD leader argued. “This means: we will work on this together.”