Relief about German coal exit deal fades as focus turns to implementation challenges

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has signalled her government is ready to move on the deal agreed by the coal exit commission last week. “The fact that a commission made up from such different societal groups has found an agreement and created a framework is an important message for us. We will handle this very carefully,” she said after a meeting with German state premiers. The deal showed “a responsibility for society as a whole and we want to live up to it,” said Merkel.

In the days following the coal commission’s agreement to exit coal-fired power generation by 2038 at the latest, politicians from Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and government coalition partner the Social Democrats (SPD) have showed support to swiftly implement the compromise. However, a first parliamentary debate on the deal made clear that tough debates on the details can be expected throughout the legislative process over the coming months.

Both Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance as well as her coalition partner, the Social Democrats, have slumped in polls and last year’s regional votes. Elections in autumn in eastern German states – including lignite mining states – loom large. Concerns that voters may perceive the deal from the coal commission as a burden had made both parties nervous as the right-wing populists are polling strongly in East Germany. European Parliament elections at the end of May present a first litmus test.

Coal state premiers want to act quickly regarding the support for their mining regions and announced they wanted to agree with the federal government on key infrastructure projects in a programme of measures by the end of April. Merkel confirmed that she planned to get the respective law off the ground by May.

A meeting between the chancellor, state premiers and cabinet members has shown that everyone “has a common idea of what we want to achieve”, said Saxony’s government leader Michael Kretschmer in an interview with public broadcaster ZDF. The commitments by the federal government to support mining regions are “very extensive and concrete”, he added. They had to be laid down in a contract between the national government and coal states which would give security beyond the current legislative period.

Germany’s task force in charge of proposing how the country can stop burning coal to protect the climate had reached a compromise on how to approach this challenging task for the world’s largest user of lignite and Europe’s economic power house, and when to complete it. The commission recommends 2038 as the final exit date, with an option to end it by 2035. In a first step, the closure of nearly one third of the coal-fired power plants by 2022 requires fast decisions and compensation talks with operators.

Parliamentarians expect to have last word

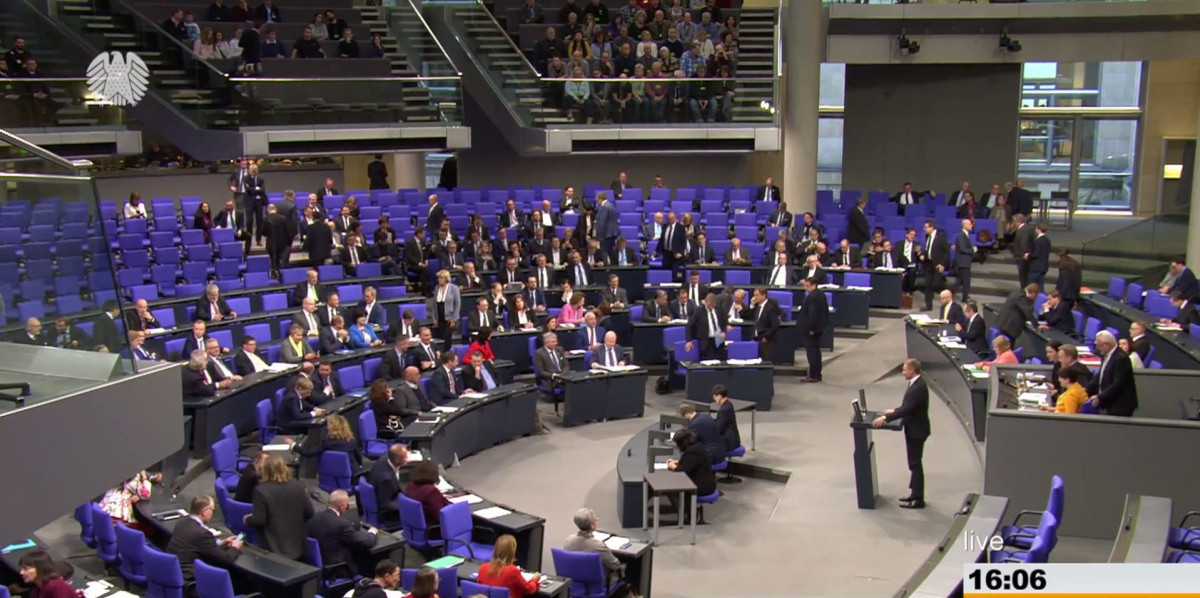

Parliamentarians from across the political spectrum, meanwhile, made it clear they expected to have the last word on all coal exit law-making. Most praised the commission for agreeing on a compromise.

The Bundestag is where “democratically legitimised decisions” on the phase out have to be made, said Christian Lindner, head of the business-friendly Free Democratic Party (FDP), which is part of the opposition in parliament. He called for debates in the plenary and public expert hearings in committee on topics such as supply security, costs for taxpayers and electricity prices.

Members of Germany’s grand coalition majority gave mixed reviews of the coal exit deal. While Social Democrats praised the compromise, some conservatives from CDU and CSU criticised individual chapters, especially the energy and climate policy sections.

“The topic supply security is not at all resolved for me, as is the question of price development over the coming years,” said Andreas Lämmel (CDU), a representative from mining state Saxony. Compensating increasing power prices with tax money, as proposed by the commission, is “completely unacceptable”, said Lämmel, who added that the debate about the costs of the proposed coal exit path “have only just begun”.

CSU member Andreas Lenz said the compromise “supplied answers in a reliable framework” on how Germany can reach its 2030 climate targets by reducing coal use. He added that the “non-binding” proposals should be “taken as cornerstones for the parliamentary debate”.

Bernd Westphal, economy and energy spokesperson of the SPD, warned of re-opening the hard-fought compromise. “It would really be a grave mistake.”

“The government must now deliver” and guarantee a swift implementation by deciding which coal plant goes offline at what moment, said the Greens’ deputy group leader Oliver Krischer. The commission’s proposal had to be understood as “the beginning of the coal phase-out, and not only as handing out presents throughout the country”.

The Left Party’s Caren Lay said a coal exit by 2038 comes too late. She welcomed the commission’s recommendations for mining region support, but criticised compensation payments for power plant operators or rebates for the industry.

Financing remains thorny issue

Overall, the question of how to finance Germany’s switch away from coal remains a thorny issue. In an interview with German business daily Handelsblatt, finance minister Olaf Scholz said that coal region support would mainly be financed from existing budgets. “We have earmarked big funds for investments; for example, in the budgets of the transport ministry, economy ministry, science ministry and construction ministry,” Scholz said.

Chancellor Merkel said it was too early to tell whether the money would come from existing budgets. The government’s mid-term budget plans cover a time period until 2023. “We’re talking about 2038. Nobody knows what the mid-term planning will be in the future,” Merkel said.

Climate NGOs say proposed exit path violates Paris Agreement targets

The debate about the proposed final exit date 2038 were refuelled when climate activist members of Germany’s coal exit commission published the text of the dissenting vote they had added to the general support of last week’s deal.

“Neither the planned final exit date 2038 nor the vague path until 2030 are sufficient for an adequate contribution to climate protection from the energy sector,” read a declaration by the commission members Martin Kaiser (Greenpeace), Kai Niebert (umbrella NGO DNR), Hubert Weiger (Friends of the Earth Germany, BUND) and Antje Grothus (Climate-Alliance Germany). But the members said they supported the compromise in general “in order to break Germany’s climate policy standstill of the past years” and because it implies a “clear entry into the phase-out through 2022” and recommends the preservation of the embattled Hambach Forest.

Coal mining state premiers said that, for them, the deal was a complete package and 2038 should remain as the final phase-out date. “The proposal must be implemented as tabled. Re-opening one provision would endanger the hard-fought compromise,” Saxony-Anhalt state premier Reiner Haseloff told news agency Reuters.

Meanwhile, coal protests continued throughout Germany. Student climate protesters, organised by the global student climate activist initiative "Fridays for Future", met in several cities across the country on Friday.