German government stands ready to move on coal exit proposal

Germany’s government has signalled a swift process to assess the coal exit commission’s proposal and start the law-making process as support and criticism for Saturday’s early-morning deal, which includes an end to coal-fired power generation, became more obvious.

The government will “closely and constructively review” the agreement and “take a few days” before conclusively commenting on the proposals, economy and energy minister Peter Altmaier told public broadcaster ZDF. “We discuss this with the state premiers, but also with the four commission heads over the coming days, and then present a plan with the necessary laws,” he said.

Germany will need two major laws to implement the phase-out plan: one on support for mining regions, the other on the timetable for coal power plant shutdowns. The government is “ready for a very quick start regarding the financing”, said Altmaier in a separate interview with ARD.

Germany’s climate protection package

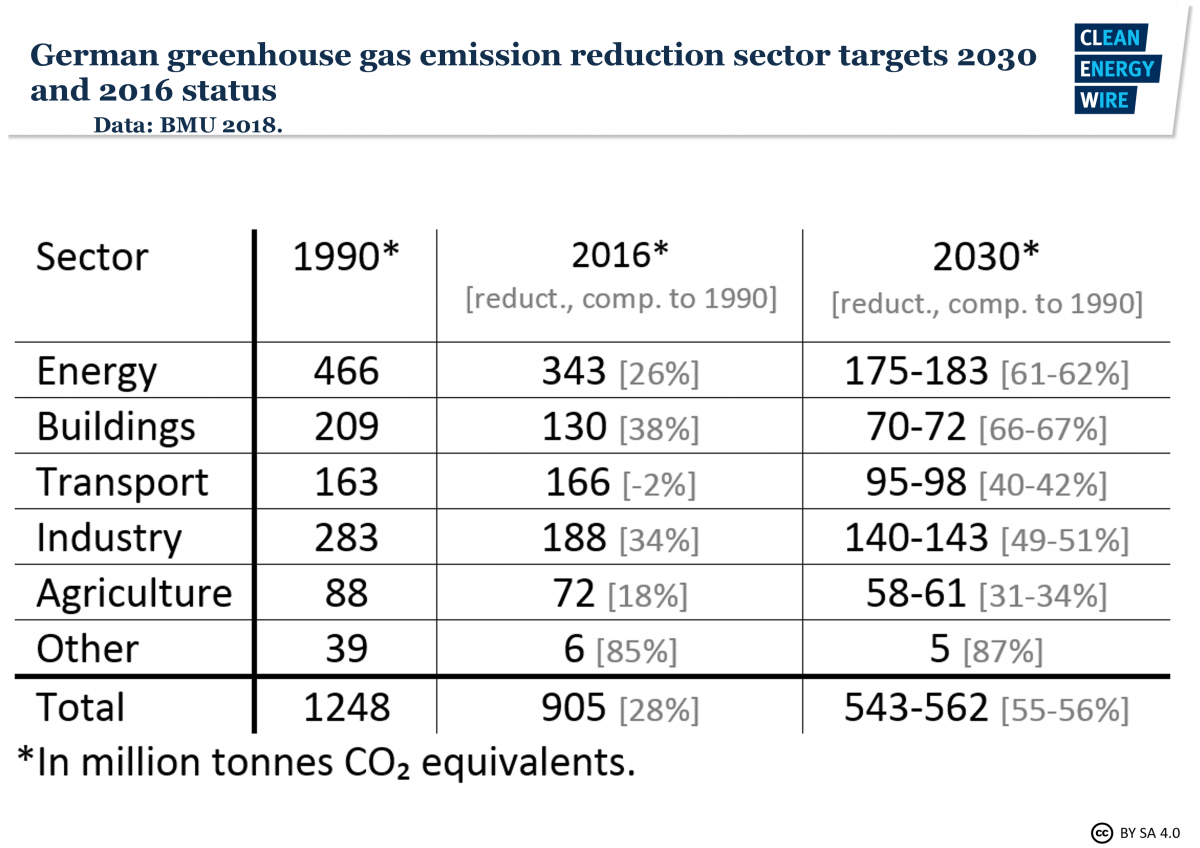

The coal exit plan forms part of the government’s Climate Action Law package, which relevant ministries currently work on and the grand coalition has promised to finalise by the end of 2019. One element of the package is a programme of measures to reach Germany’s 2030 climate targets in each economic sector, including energy supply.

Coal commission co-head Ronald Pofalla, former chief of Merkel’s chancellery, said the government would prepare the legal framework for the measures to support structural change by the end of April. “And then the German Bundestag [federal parliament] has to be convinced, and in the end the Bundesrat [council of federal state governments] has to agree. So it’s a very complex and unstable process,” said Pofalla. He added that the three German parliament members, who attended the coal commission meetings without voting rights, throughout the process had signalled if things were discussed which would have been “difficult to implement” in the Bundestag later.

The legal framework for the coal phase-out path and the compensation talks are expected to take longer. The government will also get a set of recommendations from a mobility commission, which is due by the end of March. However, first leaked suggestions have created a significant stir and transport minister Andreas Scheuer has rejected ideas such as a general speed limit on highways or higher fuel taxes outright.

No cakewalk ahead

Environment minister Svenja Schulze said the implementation of the commission’s proposals “will surely not be a cakewalk”. First, economy minister Altmaier has to examine the phase-out path proposal, then the federal parliament will “decide the concrete individual steps,” she told Deutschlandfunk.

Over the weekend, Germany’s task force in charge of proposing how the country can stop burning coal to protect the climate had reached a compromise on how to approach this challenging task for the world’s largest user of lignite and Europe’s economic power house, and when to complete it. The commission recommends 2038 as the final exit date, with an option to end it by 2035.

In what many environmental NGOs see as a “quick” first step, Germany should switch off 12.5 gigawatts (GW) of capacity by 2022. By 2030, coal-fired power generation should fall to a maximum of 9 GW in lignite and 8 GW hard coal, well below half of 2017’s capacity. The deal would allow Germany to “certainly reach” its 2030 climate target for the energy sector if it is implemented by the government, said commission co-head Barbara Praetorius.

The commission recommends settling questions related to compensation for operators of lignite plants as well as for employees in “mutual agreements.” The task force did not put a number on financial support for mining regions, but German states can expect 40 billion euros over twenty years from the federal budget.

While many countries have already set out proposals for a coal exit, “none of those plans are of the scale laid out in Germany, an industrial giant that currently relies on coal for almost a third of its energy needs,” writes Melissa Eddy in an article for the New York Times.

The task force proposal is not binding, but the government is widely expected to follow its recommendations because of the multi-stakeholder make-up. Still, the commission’s compromise is subject to the regular legislative process and thus parliamentary approval.

Speed not right, too expensive

Overall, the highly anticipated phase-out proposal was welcomed by most NGOs, researchers, and business associations. However, in a dissenting vote regarding the final exit date, environmental NGOs showed their dissatisfaction with the proposed phase-out speed. “The end-date of 2038 is inacceptable,” said Martin Kaiser, co-managing director of Greenpeace Germany and commission member. His and other organisations especially criticise the vagueness of post-2022 plans and would have liked to see clear plant shutdown provisions for every year until 2030.

The international non-profit climate science and policy institute Climate Analytics said that with this plan, Germany would be the only EU country to announce a coal phase out later than 2030, “setting dangerous precedent”.

Political analyst Arne Jungjohann called the proposals the “result of the big politics machinery”, “much too expensive and much too slow”. However, once enacted it would help build acceptance, planning security and future perspectives for the mining regions.

Business leaders, who had warned that an “overly-hasty” exit from coal could inflate power prices, also welcomed the plan. However, Germany’s largest electricity producer RWE said it will have to make significant job cuts. “I expect a significant reduction already until 2023 which will go far beyond what is planned so far and can be done through normal fluctuations,” the company’s CEO Rolf Martin Schmitz told Rheinische Post. Schmitz said he expects the lignite plant shutdowns by 2022 to largely take place in North Rhine-Westphalia – where RWE’s mines are located – consistent with what some coal commission members have indicated as well.

Schmitz also said the company was open to talk about keeping the embattled Hambach Forest, which has become a symbol for climate activists as RWE wanted to cut it down for an extension of its open-cast lignite mine. The commission had said preserving the forest would be “desirable”.

Meanwhile, analysts say the coal exit deal could supply RWE with a boost in the eyes of investors, as the company is set to receive compensation for plant shutdowns and “job guarantees that the nuclear industry had to fight for in court,” reported Bloomberg. RWE’s shares had gone up last week, when a leaked draft of the coal commission’s final report already proposed compensation payments for early closure.

Support for mining states

Lignite mining state Brandenburg’s premier Dietmar Woidke said the deal was a “good result for [the mining region] Lusatia, for climate protection, energy security and acceptable power prices.” Now it was up to the federal government and the parliament to implement the proposals “as fast as possible.”

Chancellor Merkel has invited Germany’s lignite mining state premiers this week for a second round of coal exit talks, according to media reports. “We will set the timetable for a package of measures, key points of which will be ready by 30 April,” said Michael Kretschmer, state premier of Saxony.

The economic prospects for coal mining regions as well as for coal workers figure prominently in the coal commission’s final report, with almost 40 pages devoted exclusively to measures aimed at cushioning the disruptive effects of a coal exit on regional economies as well as on the industrial value chains of the country as a whole. Federal environment minister Schulze said the government must closely examine how the financial support for the mining regions is used and make a plan to ensure that it will “result in something that avoids CO₂.”