Preview2018 - Next German government faces urgent coal choice

Government formation

September’s elections delivered a blow to the incumbent grand coalition of Germany's two biggest parties. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD) both suffered heavy losses at the ballot box and the ensuing difficulties in government formation are unprecedented in the country.

After the Jamaica talks between the conservatives, the pro-business FDP, and the environmentalist Green Party collapsed in late November, the country is headed for another grand coalition – although for now the SPD remains reluctant to enter into a constellation that it says was voted out in September. It therefore mulls either tolerating a conservative minority government, experimenting with a non-binding form of cooperation with the conservatives, or even agreeing to hold new elections.

In any case, the current government gridlock is likely to persist for another few months, and a new government will probably not be formed before spring. While this uncertain situation falls short of constituting a political crisis in a country with strong federal states and robust constitutional procedures that serve as guidelines during such a stalemate, it casts a shadow over all of Germany’s major policy endeavours, as most decisions with long-term implications will lay idle before a new government enters office.

“The most important issue will be who is going to form Germany’s new government and what its energy policy is going to look like,” says Tina Löffelsend of the environmental organisation Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND). She argues that it depends on the next government’s ambitions whether the country will stagnate or make progress on climate and energy policy matters, such as phasing out coal-fired power production or lifting the cap on expanding renewable energy sources.

In the run-up to September’s elections, the Clean Energy Wire asked German energy and climate stakeholders about their hopes for the next government. Their answers, ranging from “a fundamental reform of the Renewable Energy Act” to “a long-term framework for the country’s energy efficiency policy” or an “ambitious CO₂ pricing with a national floor price” hint at the scope of challenges any new administration will be facing.

COP24, digitalisation, state elections and everything else...

Apart from several key policy areas discussed below, 2018 will be filled with a multitude of other major and minor developments and events that also will shape the course of Germany’s Energiewende. This includes the growing importance of digitalisation and technologies such as blockchain for the future course of a smart and decentralised energy system; the UN climate conference COP24 in Poland; state elections in two of Germany’s economic powerhouse regions, Hesse and Bavaria; the end of hard coal mining in Germany; the debate over the controversial natural gas pipeline Nord Stream 2; the ongoing phase-out of nuclear power; and the search for a final nuclear waste repository.

2020 climate target

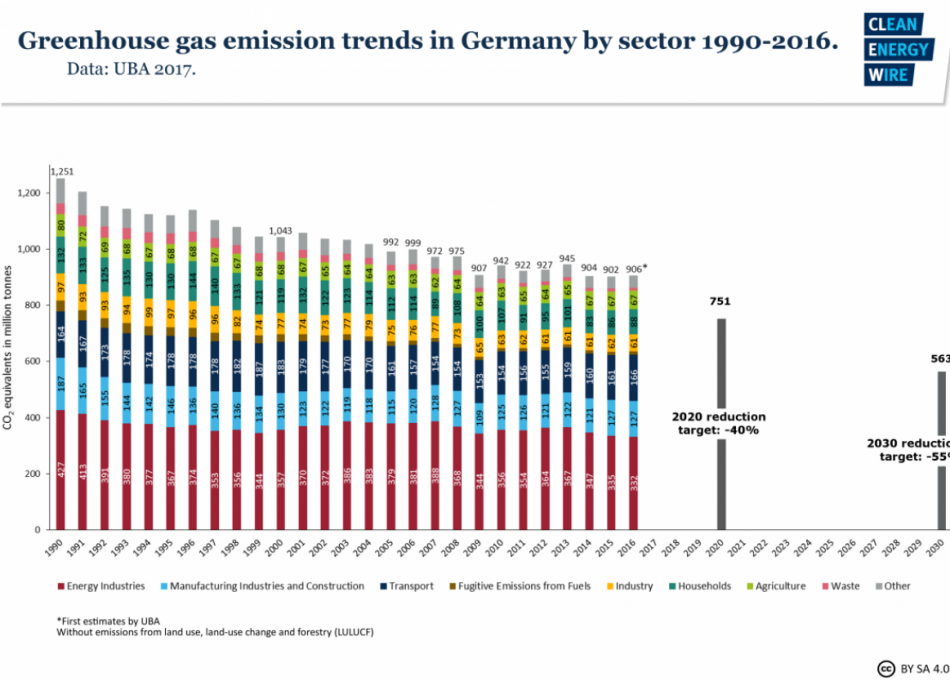

The fact that Germany is headed for missing its self-imposed 2020 emissions reduction target adds further urgency to resolving the governmental standoff, Löffelsend says. “What counts in the end is that Germany achieves this target,” she says. “Because otherwise all of its subsequent targets could no longer be met.”

In contrast, Sebastian Bolay from the German Association of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) says a hasty coal exit would push up power prices and might endanger supply security, thus undermining German industry’s competitiveness. “To reach the targets set for 2030 and beyond, it is much more urgent for us to cut emissions in the transport and heating sectors,” Bolay argues.

Germany has pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emission by 40 percent by 2020 compared to 1990 levels. This happened in conjunction with the EU’s contribution to reaching the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal to largely decarbonise the world’s economy by the middle of the century. But, according to Germany’s environment ministry (BMUB), emissions reduction will rather end up below 33 percent if no additional measures are taken.

If the country fails to fulfil its own climate ambitions, this would cost its political credibility and economy dearly, energy economist Claudia Kemfert says. “The longer climate protection is postponed, the higher the economic costs and disadvantages for the whole economy will be,” Kemfert argues, adding that initiating a coal exit soon was the only way to avert a climate policy disgrace.

Michael Schäfer of the environmental organisation WWF says that phasing out coal is crucial for reaching the 2020 goal, but adds that an overall “emergency programme for our climate policy” is needed to make meaningful progress. He says other measures, for example tax credits on retrofits of polluting cars, energy efficiency regulations for buildings, and a transition towards electric mobility, also have to be introduced quickly to stay on track for the next target year and the following goal in 2030.

However, other climate policy observers, such as economist Andreas Löschel, who heads the advisory board authoring the German government’s energy transition monitoring report, suggest that more calmness with respect to 2020 is advisable. “We wouldn’t really need to be right on target for the 2020 goal, if there were signals that we’re on the right path for the long-term goals,” he says.

Coal exit

Löschel argues that the debate over how many gigawatts (GW) of coal capacity can be taken off the grid focused too much on the short run. In the failed Jamaica talks, the conservatives and the FDP proposed to retire up to 5 GW, while the Green Party called for 8-10 GW. A compromise between the parties envisaged the decommissioning of 7 GW by 2020, the equivalent of Germany’s 15 most carbon-intensive coal plants.

The talks’ collapse ultimately scrapped this agreement, but in a surprise move, the SPD, which traditionally has close links with the coal industry, has recently announced that reaching the climate targets would have to go “hand in hand with an end to coal-fired power generation.” SPD head Martin Schulz insisted that this cannot be achieved “from one day to the next,” and protecting coal workers’ economic interests had to be paramount for a just transition. The future of coal-fired power production is now also likely to figure prominently in potential coalition talks between the Social Democrats and the conservatives. Also, the coal exit commission proposed in the Climate Action Plan 2050 might start its work in 2018, environment minister Barbara Hendricks said.

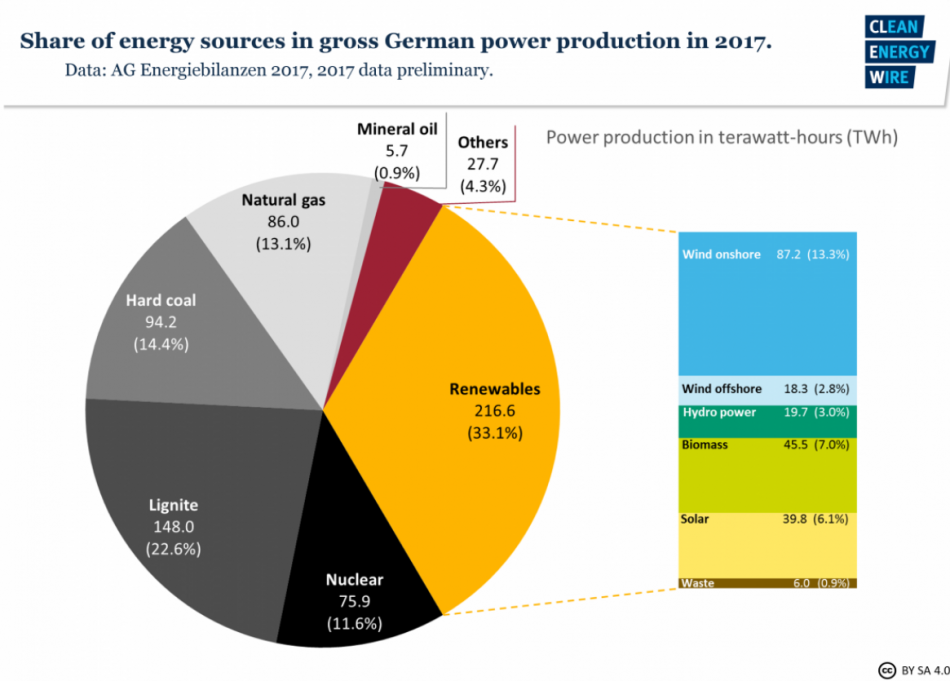

The share of coal in Germany’s power generation already fell from over 40 percent in 2016 to 37 percent in 2017, and this trend is almost certain to continue over the next years, the head of Germany’s largest utility association BDEW, Stefan Kapferer, argues. He says a market-driven coal exit in Germany has long begun, irrespective of political decisions. “The reduction of coal-fired power production is in full swing,” he says. The BDEW estimates that Germany’s installed coal capacity could fall from the current 46-plus GW to about 20 GW by 2030, which would help the country meet its climate targets without compromising on supply security.

However, the recent drop in coal’s share has yet to bring about a reduction in emissions. According to forecasts by the energy market group AG Energiebilanzen, energy-related emissions stagnated in 2017. But Kapferer says the growing share of renewables in Germany’s power production ensures that the country’s power sector is well on its way to meet its sectoral contribution to the 2020 goal. The main culprit for lacking overall progress was the transport sector, which “so far hasn’t made adequate contributions” to reducing CO2 emissions.

Transport

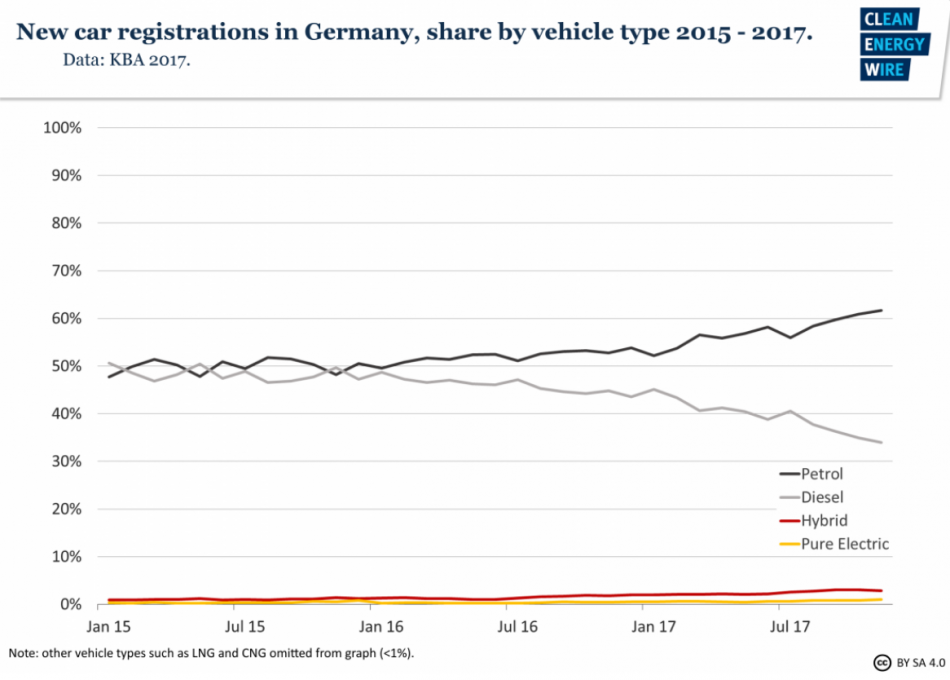

Emissions in Germany’s transport sector have barely decreased, if at all, since 1990 as higher traffic volumes set off efficiency gains for individual vehicles. Moreover, in year three after the ongoing dieselgate scandal broke in September 2015, the share of diesel cars among new registrations is falling, but sales of diesel fuel have risen to record levels in Germany. At the same time, a lack of charging infrastructure and high prices continue to keep sales of electric vehicles at marginal levels, far below the trajectory needed to meet the official government goal of having one million e-cars and plug-in hybrid vehicles on the road by 2020.

Energy economist Kemfert says the government could intervene in 2018 by abolishing the favourable taxation of diesel cars, and at the same time introducing a quota for e-cars, ramping up investment in infrastructure, and promoting alternatives to individual motorised transport. “A sustainable transformation of the transport sector is urgently needed,” she says.

Matthias Müller, CEO of Germany’s largest carmaker VW, has recently stunned his company’s competitors by proposing an end to diesel tax breaks to facilitate the shift to e-cars. However, the transport ministry (BMVI) rejected the idea, arguing this would equal an “expropriation of millions of diesel car owners.”

But diesel car owners already face a more specific obstacle in early 2018. On 22 February, the Federal Administrative Court will deliver a verdict in a case that could ban diesel cars without modern emissions control systems from entering inner cities. The government announced it would invest around one billion euros into an ad hoc programme that includes a set of measures to avoid the ban.

An e-car quota has also been proposed by the government’s Advisory Council on the Environment (SRU), according to which at least 25 percent of new cars and light trucks should be pure electric by 2025. But Germany’s carmakers seek to avoid such an imposition by announcing ambitious plans to get electric car sales off the ground in 2018.

Renewables expansion

In contrast to the plans for e-mobility, the roll-out of renewable energy sources in Germany is running ahead of the government’s schedule. According to preliminary figures published by the BDEW, the country has already surpassed its 2020 goal of 35 percent renewables share in gross power consumption. BDEW head Kapferer says that wind turbines, solar PV panels, and other renewable sources “might well take the lead next year” and become Germany’s most important power source ahead of coal in 2018.

Yet, Tina Löffelsend of the BUND worries that the current expansion rate of renewable sources may still fall short of satisfying the needs of an economy which is set to increasingly rely on electricity as its main form of energy. She says auctions for renewables and the cap on expansion volumes hinder Germany’s sector coupling, the emerging electrification of transport, heating, and industry processes.

“Sector coupling is an aim that all parties subscribe to, even if they are not the most fervent defenders of the climate,” she argues. An appropriate conclusion in this case would be to double auctioned volumes for wind and solar power. The auction mechanism itself would also have to be amended, as it currently produces “disastrous” results for wind power companies by accepting projects that may never be implemented due to lacking construction licenses. The wind power industry has warned that despite robust expansion prospects in 2018, an unchanged auction system might lead to a cliff in 2019.

Also, utility lobbyist Kapferer says that “a rupture” in expansion remains a possibility if the auction mechanism is not amended, adding that the government must add further auctions if the problem of lacking licenses persists. However, the BDEW head says that expanding Germany’s power grid is “an absolute priority” as it is essential for delivering additional renewable power from its source regions to industrial centres.