Merkel prepares departure in shock move at key time for climate policy

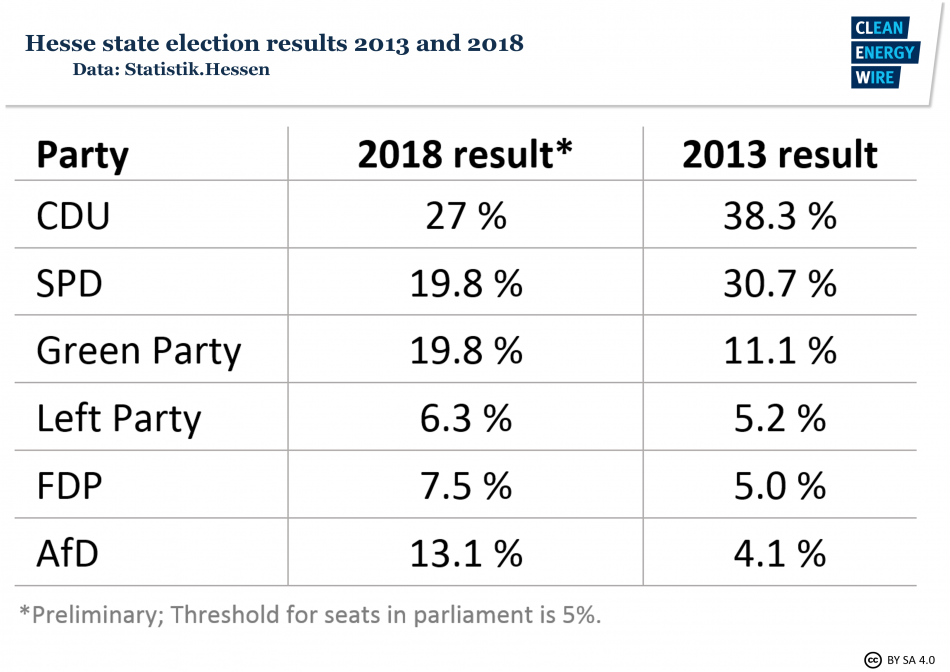

The parties that form Germany’s national government coalition took a severe hit in Sunday’s Hesse state elections, sending shockwaves through the country’s political system. Two weeks after a disastrous result for Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative alliance CDU/CSU and the Social Democrats (SPD) in Bavaria, voters abandoned these traditionally mainstream parties in Hesse, with more than ten percentage-point losses each compared to the 2013 election. Instead, Hessians flocked to the Green Party and the right-wing nationalist AfD, with each party adding about nine percentage points to their voter share.

The heavy losses prompted Merkel to announce she will not run for the position of chairwoman of her Christian Democratic Union party again and intensified a debate within the SPD over whether the party can survive politically if it remains in the so-called Grand Coalition with the conservatives at the federal level. Amid talk of a fizzling coalition and possible snap elections, it has become increasingly unclear if or how the government can still implement difficult and complex energy and climate policies, such as the management of Germany’s coal exit or the lingering diesel emissions crisis.

Internal quarrels and a poor track record on important policy decisions have plagued the coalition since it began to govern in March. The government’s internal weakness comes at a time of crucial decisions for the future of Germany’s role as a progressive energy transition country. The so-called coal commission has been tasked to manage the phase-out of coal-fired power generation in the country and is due to come up with an end date by the COP24 in Poland in December.

Chancellor Merkel's foreseeable departure and the uncertain stability of the government coalition are unlikely to stabilise the German bargaining strength at the summit that brings together dozens of countries with widely diverging negotiation goals. And the uncertainty might also spill over to the coal commission itself, where individual interest groups could try to run out the clock as the government's continuity becomes more questionable.

The government also has promised to introduce a climate protection law in 2019 in order to guarantee that Germany meets its 2030 emissions reduction targets in line with the Paris Agreement. After already postponing the 2020 climate target, Germany is under pressure to find a lasting solution for the emissions from cars, as the diesel scandal continues to cause negative headlines and impacts on German citizens through looming diesel driving bans in major cities.

Coming under fire for the rocky start and election losses, Merkel said her decision to leave the CDU leadership to a successor after 18 years could help the government finally focus on its work again. Merkel said the “bitter” election result in Hesse was “a clear signal that things cannot go on as they are,” adding that the government work recently “did not met my own quality standards.” Merkel said she would not seek re-election as CDU chairwoman at the party conference on 7 December and that she intended to step down from politics after the current legislative period, which ends in 2021. However, she added that she plans to continue her work as chancellor until then.

“It’s time to open a new chapter,” Merkel said, adding that her party now had the opportunity to prepare itself for the time after she was gone. Asked whether she feared becoming a ‘lame duck’ in office after announcing her retirement, the chancellor answered that it was quite possible to conduct successful policy even with the end of her chancellorship in sight and that the goals formulated in the Conservatives’ and SPD’s coalition agreement would guide her approach. “I want this government to work successfully – it was difficult enough to form it,” Merkel said.

Merkel's decision could help end deadlock in energy and climate policy

As soon as Merkel made her decision public, possible candidates for the future CDU leadership emerged. Besides current CDU secretary general Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, a close inner-party ally of Merkel, other conservative figures like former parliamentary group leader Friedrich Merz or current health minister Jens Spahn have said they intend to run for the position. Another possible contender is the moderate Armin Laschet, current state premier of Germany’s western coal state North Rhine-Westphalia. Although not a formal prerequisite, leaders of the CDU have traditionally been likely candidates for becoming German chancellor too.

After the coalition party's drubbing in Bavaria, some observers had already wondered if the current coalition could still muster the strength to drive policies such as the ones planned on climate and energy forward. But Christoph Bals of NGO Germanwatch said Merkel’s move might well turn out to be conducive to progress in Germany’s climate and energy policies. “I expect that this will speed things up,” Bals told the Clean Energy Wire. The success of the Green Party in elections in Bavaria and Hesse shows how important the climate crisis and the Energiewende, Germany’s energy transition, are for the country’s voters, he said. “There’s a lot of tailwind out there for daring policies,” Bals said, adding that many difficult debates, such as over a CO2 price in Germany, had been put on hold until after the state elections. “I expect the economy ministry and the environment ministry to become active now.”

The SPD’s worst-ever result in its former stronghold Hesse has intensified internal calls for leaving the grand coalition at the federal level in order to consolidate the party as an opposition force. Kevin Kühnert, head of the SPD youth organisation Jusos and a fierce critic of his party’s alliance with the Conservatives, said the SPD had to brace for snap elections. “It’s obvious that the government parties are losing their control over what is happening,” Kühnert told public broadcaster Phoenix, adding that no-one could say how long the coalition would last and the SPD should examine whether the alliance is still viable.

SPD leader Andrea Nahles said the government’s situation was “unacceptable” at present but leaving the coalition was not on the table for now. However, Nahles said her party would thoroughly examine progress in key policy areas, for example on the climate protection act, and decide whether it will remain in the coalition by the government’s “half-time” in late 2019 or early 2020.

Greens continue to soar, become country's second biggest party in polls

In stark contrast, the Green Party celebrated another regional election success after its strong showing in Bavaria. Almost on par with the SPD, the Greens turned out as Hesse’s second strongest party, gaining nearly nine percentage points since the previous vote. Although the state party’s popular top candidate Tarek al-Wazir had reasons to hope he might become Germany's second Green state premier, his party’s gains mean he can continue its current state coalition with the CDU, in spite of the latter’s heavy losses.

Al-Wazir said his party was “this election’s winner,” adding that the result was a clear mandate to continue its work on a sustainable transition in the energy, transport and agriculture sectors and to endorse an open and liberal society. With a view to the bickering within and among the conservatives and the SPD at the federal level, al-Wazir said his party’s task was to “take care of concrete issues” instead.

Green Party leader Robert Habeck said his party was right to pursue “objectiveness and expertise”. “Germany’s politics have become more populist,” Habeck told supporters after the elections in Hesse. The Greens’ decision to take the opposite approach and instead seek to convince through constructive ideas had been the right decision in Bavaria and Hesse, he said. “We’ve given a clear signal that elections cannot only be won by currying favour from the right,” Habeck said. Clear “pro-European prudence and an anti-populist stance” had proven to be election winners, he said.

The state election results were mirrored in a nationwide poll published on Sunday, which showed support for Merkel’s conservatives has fallen to its lowest point in post-war Germany. Only 24 percent currently back the CDU/CSU alliance, the survey commissioned by newspaper Bild am Sonntag found. Respondents also reduced the support for the SPD to merely 15 percent, meaning that the coalition of the two parties that used to dominate the country’s political landscape uncontested for decades no longer has a majority.

Meanwhile, the Green Party also continued its national ascent in the poll to reach 20 percent, making it Germany’s second biggest party, while the right-wing nationalist AfD was backed by 16 percent of respondents. The pro-business FDP and the Left Party both reached 10 percent.

While prominent Green figures like Daniel Cohn-Bendit, a former Member of the European Parliament, said the idea of a Green German chancellor “is no longer absurd,” the party is still far from securing the place as Germany’s strongest left-centre camp. In the 2017 federal elections, the Greens received 8.9 percent of the votes – and celebrated the result as a formidable success.

But for Christoph Bals of NGO Germanwatch, the environmentalist party’s string of election wins is more than just a temporary reaction to the weaknesses of the Conservatives and the SPD . “The discourse around the world has shifted,” Bals said. The CDU/CSU and the SPD have avoided clear-cut answers to pressing questions on climate and economic inequality, and thus lost voters, he said. “The Greens have said much more clearly where they see solutions for these challenges.”