How a Hessian county outpaces Germany's energy transition

To find hidden champions of Germany's energy transition, it's worth looking beyond the well-known cities like Berlin or Munich. Years of grassroots activism, business-savvy local farmers, and committed administrations have made the county of Marburg-Biedenkopf a best practice model of the Energiewende.

The county of some 241,000 inhabitants, situated roughly in the middle of Germany, boasts ten villages that aim for 100-percent renewables by 2040, getting all their heat and power from biomass fired in combined heat and power (CHP) plants; rural electric car-sharing clubs; and annual, crowd-sourced and financed awards for citizen-driven sustainable consumption and renewables. With the picturesque medieval university town Marburg as their administrative centre, the county's villages have banded together to engage in common goals such as the Energiewende.

Marburg has a history of green activism. Members of its university community and local citizens got involved in West Germany’s environmental and anti-nuclear energy movement in the 1970s and 80s that laid a cornerstone for progressive thinking about energy and climate policies. And engaging for the environment still plays an important role in the central Hessian region.

Nearly a third of the county’s schools now meet the exacting “passive house” standards for energy efficiency. The high standard of these public buildings is only one of many examples in the region where citizens and strongly pro-Energiewende officials have teamed up to adopt challenging targets and take the initiative to access state and federal funding.

More ambitious than Berlin

In the mid-1990s, the city of Marburg and the local Stadtwerke gave homeowners grants to improve their energy efficiency. Soon after, the city began retrofitting schools, sports facilities and other public buildings.

In the 2000s, local farmers became part of the German bioenergy boom following the introduction of the Renewable Energy Act (EEG). The federal law guaranteed above-market rates for renewable power fed on to the grid, and farmers found they could make a good income generating power from fuel crops or agricultural waste. Marburg homeowners, meanwhile, began investing in rooftop solar arrays.

Thomas Madry, one of the county’s climate protection advisers, credits these homeowners and farmers as the country’s early Energiewende pioneers. “It was very much bottom-up initiative at first,” he told Clean Energy Wire.

The first external funding came from the county’s federal state of Hesse, which agreed to reimburse 90 percent of a 50 million euro investment for insulating schools over five years. In 2008, Marburg-Biedenkopf became one of the first counties in Germany to take part in the 100 percent Renewable Energy Region programme – a brainchild of the Federal Environment Ministry and the Federal Environmental Agency (UBA) – which sought to identify, advise and network localities interested in going all-renewable.

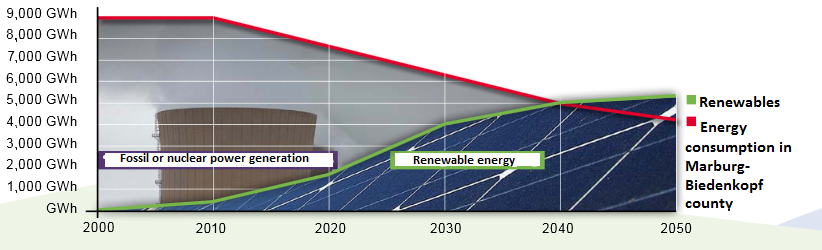

The programme provided no funding but Marburg-Biedenkopf pledged to obtain all of its power and heat from renewable, regional sources by 2040, thus making its goals significantly more ambitious than those of other counties, states, or the federal government. Berlin aims to source at least 80 percent of the power consumed in Germany from renewables by 2050 [See the CLEW factsheet Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions and climate targets].

In 2011, the county set out its strategy to reach these goals with its Integrated Climate Protection Concept. In the concept’s preface, county administrator Robert Fischbach underscores that in addition to CO₂ reduction, Marburg-Biedenkopf intended to tap into funding to generate its own energy, increasing value added to the county. There were strong financial incentives behind the transition, not just idealism.

The county extended its targets in 2012 with its Master Plan 100% Climate Protection, which pledges to reduce greenhouse gasses by 90 to 95 percent by 2050 and cut the county’s energy consumption by half. The four-year Master Plan, which started in 2014, funded two “master plan managers” who work in and for the county. (The National Climate Initiative funds two further experts in the county.)

"They need us and we need them"

In addition to power and heat, the plan includes strategies for decarbonising transportation, forestry, agriculture, lifestyles, and the commercial and industrial sectors. This is being achieved with federal funds, which, under the Master Plan 100% Climate Protection, cover most of the project costs in poorer municipalities, and 65 percent in all others.

Madry says the county’s close cooperation with the Hesse legislature in Wiesbaden has also played a key role in implementing the transition. Hesse’s own climate action plan is, unlike federal plans, aimed at municipalities and counties, and includes ample funding for implementation, says Madry.

“We had members on the coordination teams,” he says. “We gave the state lots of feedback, and were able to access funding for electromobility. They need us to hit the targets and we need them for financial support and expertise. So we’re working together very closely.”