Cities and municipalities spearhead local transport revolution

The German map is dotted with dozens of de facto laboratories testing cutting-edge technology and innovative designs for sustainable urban transport. They have names such as Bremen and Augsburg, Berlin and Iserlohn. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, the projects underway in these towns and cities – and many others, too – could provide crucial aspects of a much bigger low-carbon transportation picture, one that is now gradually coming into focus in Germany.

Katrin Dziekan, of the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA), says a new age of mobility and transportation policy is now on the horizon. Germany’s Climate Action Plan 2050, agreed last year, underscores that transport will be key if the country is to meet its ambitious climate goals for 2030 and beyond. CO₂ emissions from Germany’s transport sector must fall 40 to 42 percent by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. Dziekan says this “means a really quite dramatic reduction”. Dziekan points out that there been no reduction at all over the last decade. “The new frameworks mean we have to act now or we’ll never reach our goals,” she says, referring also to the Paris Agreement, which Germany signed in October 2016.

German cities, towns, and villages, as well as counties and municipalities, are implementing a wide range of innovations in their transportation systems. These include experimental pilot projects funded by institutions ranging from municipal utilities (Stadtwerke) to the EU. Most are financed, at least in part, by Germany’s federal ministries or the Länder.

No single city will serve as a blueprint for others. Different localities are trying out bits and pieces of a future intelligent, low-carbon transport system, elements and combinations of which could be right for other towns and cities. Their object is “urban transport energy efficiency”, which the International Energy Agency (IEA) defines as “the maximisation of travel activity with minimal energy consumption through combinations of land-use planning, transport modal share, energy intensity and fuel type”.

Anne Klein-Hitpass, urban mobility expert at Berlin-based think tank Agora Verkehrswende*, says cities and localities are crucial to a genuine “Verkehrswende”, or transportation transition. She says every German city and town is now in the process of a transformation - and that’s only in part driven by climate protection. “Germany’s cities are all asking themselves, how can we become more liveable, more attractive to families and younger people?” she says.

“Creative urban planning and different kinds of low-carbon mobility are essential parts of this thinking. This isn’t just a question of technical efficiency but of human behaviour and urban planning. It’s about organising mobility,” Klein-Hitpass adds, underscoring the role digitalization will play in how people and goods move through the low-carbon cities of the future.

In the jargon of the field, the trend is towards “multimodal transport”, which means the use of different modes of transportation – bicycle, walking, electric vehicles, car sharing and public transport, among others – to get around a city in a way that is friendly to the climate, but also to fellow city-dwellers who value clearer air, less noise, quicker passage, and more space (for example, for parks rather than car parks). One strategy to find the right mix of mobility options is called “avoid-shift-improve”. Planners must find ways to “avoid” motorised travel as far as possible through city planning and travel demand management. And there must be policies to “shift” movement from private, motorised travel to more energy efficient modes. Lastly, “improve” policies cut energy consumption and emissions through, for example, more efficient fuels and vehicles.

“Our primary policy path in mobility is finding ways to link public transportation, bicycle and walking, and car sharing,” says Carsten Hansen, of the German Association of Towns and Municipalities (DStGB). “We want to reduce the number of cars and create space for our citizens,” he says, noting that while electric and other “green” vehicles have a role to play, they are just one piece of the puzzle. Hansen says that, on the municipal level, a lot can be done with relatively small sums of money through traffic codes and zoning laws. Traffic or motor vehicle codes are laws, ordinances and rules that regulate the interaction of motor vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians on public properties. Zoning laws or ordinances regulate the use of spatial areas for residential or commercial purposes, as well as lot size, placement, bulk and the height of structures.

“We can do a lot,” he says. “But there’s always going to be a political fight over it if, for example, you hurt car owners. These policies aren’t always popular.”

Michael Cramer, a German Green Party Member of the European Parliament (MEP), is even more explicit that the current debate is far too centred on replacing Germany’s current fleet of motorised vehicles with new, low-carbon models. “They still make noise, use energy and take up space,” he says. “And the charging stations are terribly expensive. It’s much more economical to find new ways to move people and goods without cars or trucks.”

Cramer points out that almost everyone agrees that bicycles must be more strongly incorporated into transportation policy. “But our policies don’t reflect all the rhetoric,” he argues. In EU cities, he says, cargo bikes could replace trucks for half of all freight transport. “Imagine that half of the trucks in our cities just disappear!”

Still, “improved” forms of motorised transportation will be a critical part of Germany’s cities of the future – and some are already testing it.

Germany has long been famous for manufacturing luxury vehicles and is finally getting into gear on sustainable mobility, after years of lagging behind trailblazers such as Norway, Denmark, and California.“ In Germany, the conundrum is still how to get e-cars on the road without sufficient numbers of charging stations,” says Benjamin Dannemann of the Renewable Energies Agency (AEE). “And likewise how to justify the expensive charging stations with so few e-cars out there.”

Yet UBA's Dziekan says a spate of recent studies has attested to the feasibility of electric mobility. Until recently, the German government refused to prioritise any one solution for low-carbon cars - e-mobility, biofuels, and hydrogen-powered vehicles. That’s different now, says Dziekan. “The new studies all show that the cheapest solution for society as a whole is electro-mobility,” she says, noting that air travel and shipping will rely on power-to-gas and power-to-liquid.

German pilot projects are beginning to flesh out a low-carbon transportation sector. While the less successful are dropped, some have distinguished themselves as models:

-

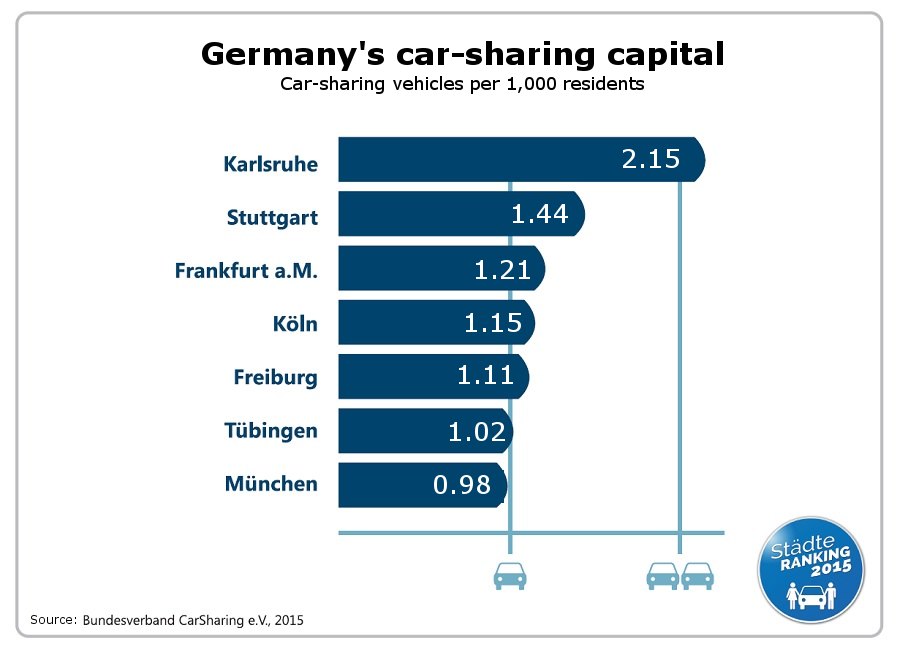

Public mobility stations in the port city of Bremen (pop. 557,000) are multifunctional sites on public streets that include low-emission vehicles for car sharing, public transport stops and taxi stands. Financed by the Bremen Stadtwerke, nearly 80 car sharing stations offer more than 270 cars to over 12,000 clients as of April 2016. Bremen estimates it has relieved the city of 4,000 private cars. (Karlsruhe, pop. 308,000, boasts the most shared cars per 1,000 citizens, at 2.15.)

-

When it comes to pedelecs, or electric bicycles, the old medieval city of Aachen (pop. 245,885) near the Dutch border is paving the way. Through the EU-funded CIVITAS DYN@MO programme, it offers a citywide pedelec-sharing-system and pedelec delivery service

-

The historical Bavarian market city of Augsburg (pop. 286,000) has all of its public buses running on bio-natural gas – thanks to Mercedes-Benz and the Augsburg public utility – and aims to have the city’s entire public transportation network CO₂-neutral in 2017

-

The small cities of Freiburg (226,393), Heidelberg (156,267), and Münster (310,039) are considered Germany’s cycling capitals. Freiburg and Heidelberg both belong to the state of Baden-Württemberg, which has its own particularly ambitious mobility strategy. Still, the college town of Münster leads the country with 38 percent of its local transportation needs covered by bicycle. Berlin and Frankfurt, however, outpace all three in terms of walking as proportion of short-distance travel.

-

The lesser known town of Iserlohn (93,537) in the region of Sauerland, south of Dortmund, boasts its own best practice project: a SmartCable that electric vehicles owners receive with a contract offered by the local public utility. The cable enables them to charge their e-cars with regional, renewable power and pay for it automatically through the cable, which removes time-consuming on-the-spot payment.

Berlin is unique in that it has a laboratory separate from the city itself, namely the EUREF Campus, partner of Berlin’s Technical University, where electric cars, buses, cargo loaders, scooters and pedelecs are networked through a high-tech micro smart grid. The EUREF Campus, which the UN recognised for “Best Practice of Global Urban Renewal” in 2013, has innovations of interest to Germany’s bigger cities. The campus itself, using a CO₂-neutral energy supply, has already hit Germany’s 2050 targets (as specified in the 2010 Energy Concept) with projects that range from smart metering to a testing platform for e-mobility with the largest recharging station in Germany. Its e-scooter sharing programme, with 150 scooters, is also considered a trailblazer.

“What’s completely original,” says Weert Canzler of EUREF Campus, “is that here we combine mobility, the smart grid and heating in one location, something our cities and towns can’t do yet on such scales.” This triad, in different constellations, is what Germany’s urban centres will eventually adopt in one form or another, tailored to their specific needs, he says.

Much of the testing that happens on campus would be complicated and even dangerous in a real city. Olli, for example, is a 3D-printed driverless electric mini-bus that makes its rounds of the EUREF Campus every seven minutes during working hours. Making about as much noise a vacuum cleaner, Olli is the product of the Arizona startup Local Motors. It is currently learning to identify street hazards such as cyclists and pedestrians, and recognise street markings and routes.

But while automated buses such as Olli are already in Helsinki, Amsterdam and Washington, DC, they probably will not be on the roads in Germany anytime soon.

“In terms of technology alone, driverless zero-emissions buses like Olli could probably be deployed in Germany in just a few years,” says Canzler. “The problem is the legal regime. We need completely new laws to get driverless e-vehicles on public roads, and there’s opposition to this in Germany. This is the obstacle, not the technology.”

In terms of sustainable mobility, the ball is now in the hands of Germany’s politicians, says Dziekan of the UBA. “We need better frameworks at the federal level in order to bring these practices to the whole country. The current laws still favour fossil fuels and private cars.”

The German parliament in May approved a law on automated driving, but a human driver will continue to have to be able to take the wheel if need be.