Germany sees largest emissions drop since 2009 recession

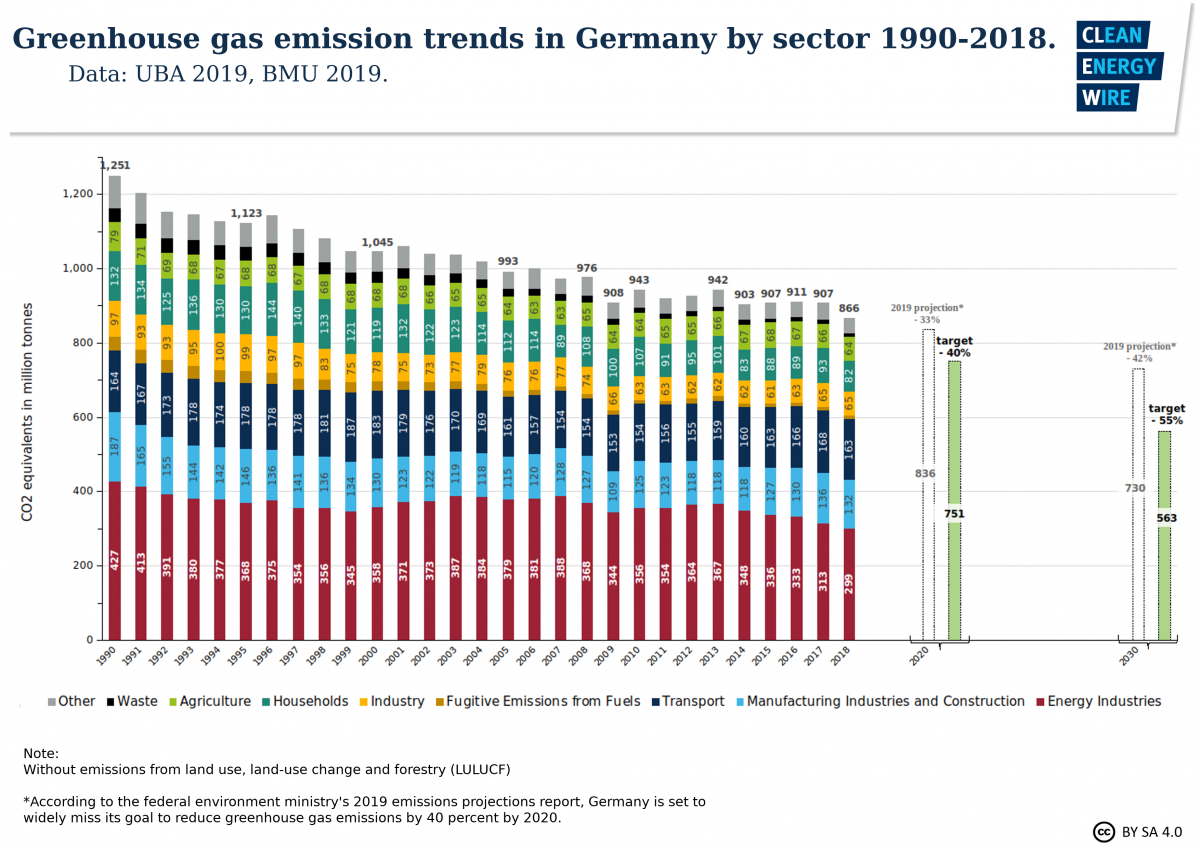

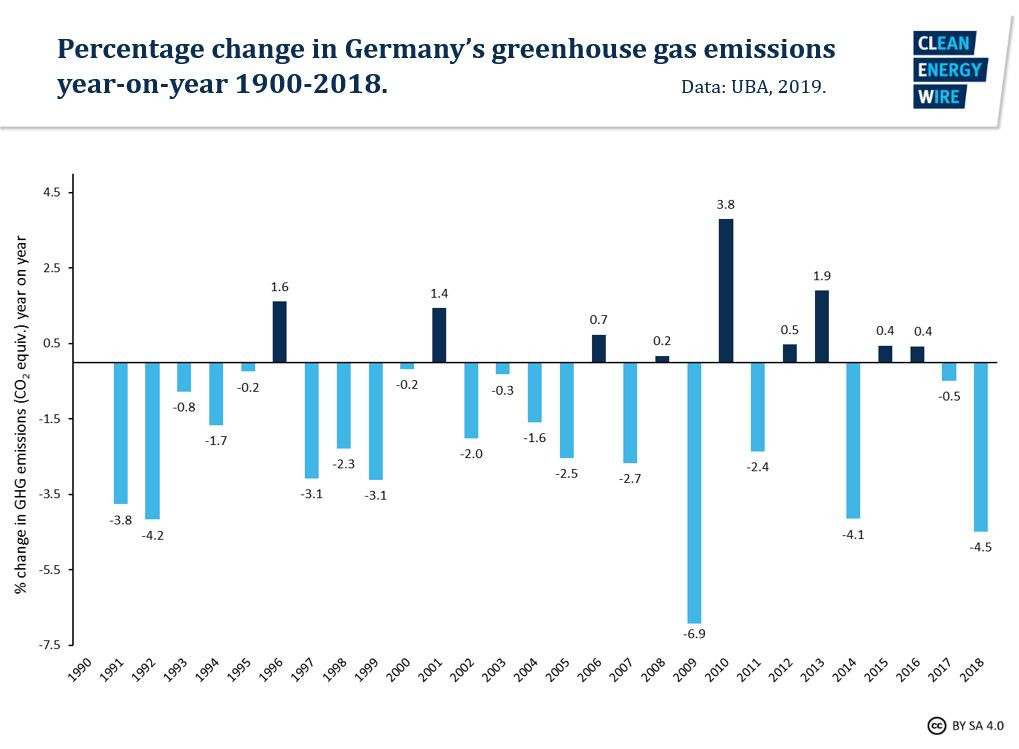

Due to a drop in fossil fuel use and high temperatures, Germany’s emissions of greenhouse gases dropped 4.5 percent to 865.6 million tonnes last year, according to estimates by Germany’s Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

“2018 was a special year for climate policy,” environment minister Svenja Schulze said at a press conference. Climate change had become “clearly palpable” during last year’s heat waves and drought, but the data showed that climate action does make a difference, Schulze said, pointing to policies like the expansion of renewable energy, the closure of some coal power plants, and the reform of the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

“Still, we have to do a lot more in the coming years,” Schulze said. She added the figures should add momentum to government efforts to step up the fight against climate change with a much-anticipated Climate Action Law this year.

After initially published figures on 2 April showed a 4.2 percent emission reduction in 2018, the UBA corrected its calculations two days later, saying it had miscalculated emissions in the agriculture sector which had fallen by 4.1 percent leading to an overall larger decrease in the country's greenhouse gases.

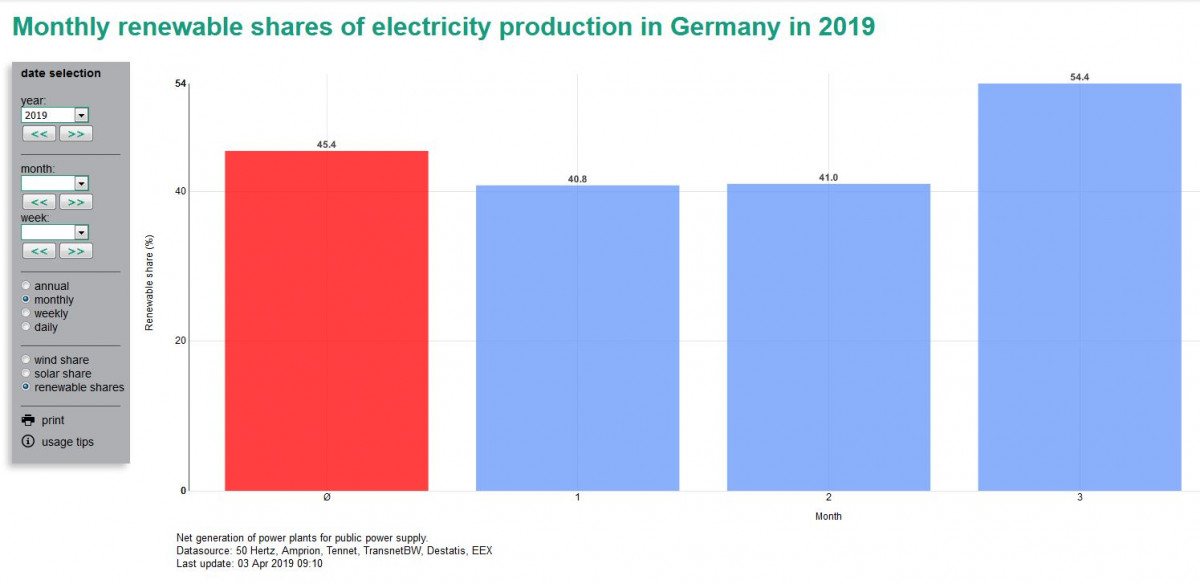

German emissions have largely stagnated for the past ten years. Though the country has achieved a remarkable increase in renewable power generation as part of its landmark energy transition (Energiewende), its track record on cutting climate-damaging greenhouse gas emissions is mixed. One major reason is continued coal-fired power production. But the country is now eyeing a coal phase-out by 2038 at the very latest, and gross renewable electricity generation almost caught up with combined lignite (soft or brown coal) and hard coal power production last year.

Looking just at net public power produced for public supply - excluding the amount of power the generating facilities (auxiliary services) use themselves to operate, or the power produced and consumed by German industry, without being fed into the public grid – renewables fare even better and have already overtaken coal.

In March, wind alone produced over a third over Germany’s net electricity, and in the first three months of 2019, renewables supplied about 45 percent of power for public supply, according to research institute Fraunhofer ISE's project Energy Charts.

To ensure progress on emissions reduction, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has introduced a "climate cabinet", which is set to meet for the first time next week. Merkel has warned that “tough decisions” will have to be made soon to reduce emissions and reach future climate targets.

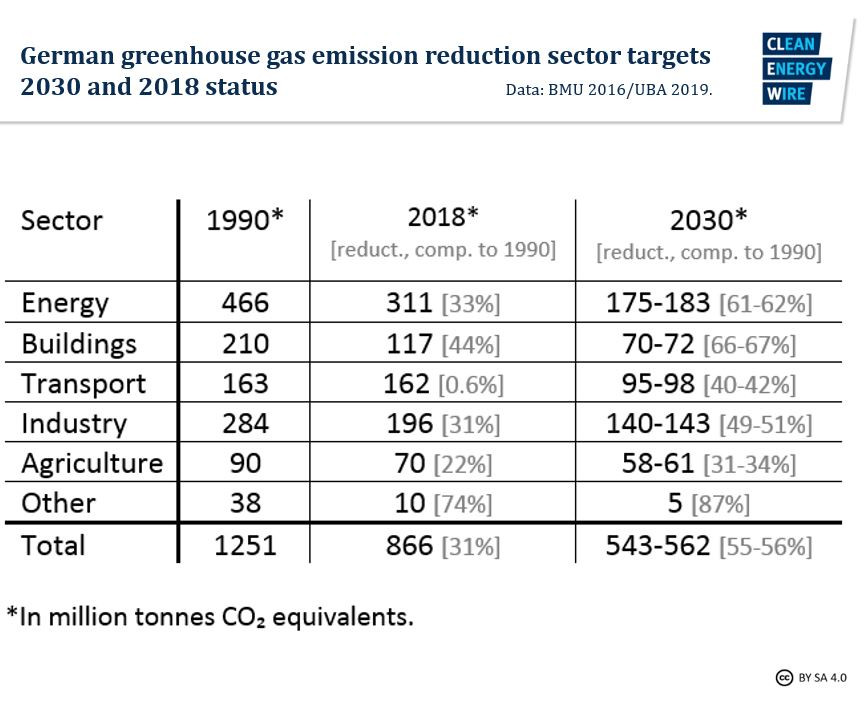

Merkel’s governing coalition has conceded that Germany will not meet its 2020 goal of cutting emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels. According to UBA calculations, emissions are now 30.8 percent below the 1990 benchmark, leaving too wide a gap to close by the end of next year. The government is now focused on its 2030 target of a cutting emissions by at least 55 percent (see graph), and the coalition plans to introduce a Climate Action Law this year to ensure they are reached.

“Today’s data provides us with the necessary tailwind to take action and create clarity and commitment in a [climate action] law,” Schulze said. Schulze is also a vocal proponent of introducing a carbon price in Germany, an idea that has been met with resistance from some of her cabinet colleagues, but is now increasingly being considered as a possible instrument to reach the targets.

“In the long run, we cannot finance the whole energy transition via power prices,” said Schulze, referring to the renewables surcharge that has financed Germany’s green power expansion to date. High power prices can lower the incentive to use electric cars, heat pumps or other Energiewende technologies that rely on electricity, she warned. “We will have to look at the whole taxes and levies system, and introduce a fairer price on CO₂,” Schulze said.

Energy sector and households responsible for majority of reduction

More than a third of the 2018 emissions drop came from the energy sector, where power production from renewables increased and coal plants were shut down or moved into standby. Higher prices for emissions allowances resulting from recent reforms of the European Emissions Trading System (ETS) were one factor leading to less hard coal power generation, the environment agency said. In addition, low water levels in rivers as a result of the drought in summer 2018 led to lower transport capacities, and thus higher prices for hard coal and heating oil.

“In a way, climate change threatens its own causes here – the supply of fossil fuels,” said Schulze.

Warm weather and higher fuel prices also significantly pushed down emissions from households. The sector contributed about 40 percent of the total reduction in 2018.

Transport emissions also fell slightly, as Germans used less petrol and diesel. The reason could be higher fuel prices, “but we are still puzzling a bit over this,” said Schulze.

Agricultural emissions decreased by 4.1 percent due to reduced numbers of cattle and pigs as well as less use of mineral fertiliser – and a smaller harvest due to the dry summer lowered emissions further, UBA writes in its corrected press release.

UBA said the data are a “detailed estimate” and preliminary. According to the agency’s emissions expert Michael Strogies, the moorland fire caused by the German army in autumn 2018 is not yet included in the calculations, but data showed that it could have released about a quarter of a million tonnes CO₂ equivalents. UBA will publish final 2018 data in January 2020.

Warm winter cannot substitute successful climate policy - NGO

Environmental NGOs criticised that government policy had little to do with the emissions drop. It has done nothing to contribute to 2018’s “meagre climate success”, said Greenpeace expert Karsten Smid. “A warm winter cannot substitute successful climate policy. Germans simply used their heating less.” The country could be able to reach its future targets if the government quickly implemented both the coal exit and a decarbonisation of the transport sector, he said.

Stefan Kapferer, head of the energy industry association BDEW, also called for more action in the transport sector. “We need significantly more speed, and must gear up regarding alternative drive technologies,” he said, calling for increased expansion of Germany’s e-car charging infrastructure.

Lukas Köhler, member of the business-friendly Free Democratic Party (FDP), sees European emissions trading as a major factor for last year’s reductions. “While the federal government outsources climate action to commissions and working groups, EU emissions trade creates facts,” Köhler said. Rising allowance prices had made hard coal and lignite less profitable. The FDP calls for including transport and buildings in emissions trading.

EU energy sector and industry emissions also fell 4.2 percent in 2018

Europe-wide energy sector and industry emissions – covered by the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) – also fell by 4.2 percent in 2018, according to preliminary data, reported Montel. The decrease was due to a significant drop in power generation and heating emissions, while CO₂ from industrial manufacturers was only slightly lower year-on-year. Rapid renewables development and higher allowance prices had pushed coal out of the market, writes Montel.