Germany heads for "spectacular" 2020 climate target miss - study

“The next government immediately has to step up its efforts to at least get the country somewhere near its target,” Agora Energiewende* head Patrick Graichen said in a statement. “Just 30 instead of 40 percent less CO2 is not just a bit off target - it’s a spectacular miss of the 2020 goal.”

Germany has made climate protection one of its priorities in its Energiewende, the country's dual shift from fossil fuel and nuclear power to a renewables-based energy system. Germany also pushed hard in July to convince the G20 group of leading industrialsied and emerging economies to step up efforts to meet the pledge of the Paris Climate Agreement, keeping all countries but the United States aboard. The next round of international climate negotiations - the COP23 - will also take place in Germany in November.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel - whose international engagement has earned her the nickname climate chancellor - is on course to win the federal election on 24 September. She will most likely have to enter another coalition, which will determine the country's future climate and energy policy, but energy and climate policy views of potential coalition partners vary widely.

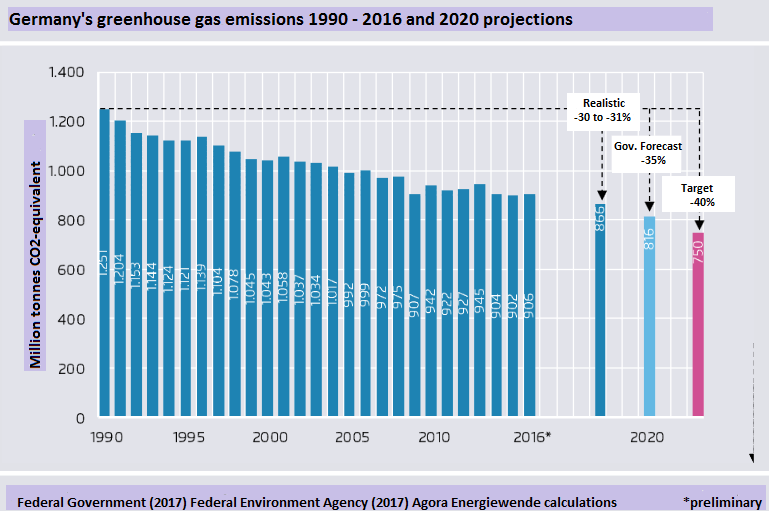

Every German government since 2007 has committed to reducing the country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2020 compared to 1990 levels. In 2016, emissions were 28 percent lower than 1990. Merkel confirmed in July that ambitions remained unchanged, although the government’s latest emissions forecast already projected a likely reduction of just about 35 percent.

But even this lower figure was “based on outdated assumptions,” Agora Energiewende said. A more realistic “business-as-usual scenario” without any additional climate protection measures being taken put CO2 emissions reduction somewhere between 30 and 31 percent, the group argued. A bigger population, higher economic growth and low fuel prices were probably causing emissions in the target year to stand about 50 million tonnes above current projections, and roughly 115 million tonnes above the actual reduction target of 750 million tonnes CO2 equivalent per year.

"Trump would be glad to rub this in our faces"

The energy transition researchers propose an ad-hoc climate protection programme to be set up by the next government that has to take effect as early as the first half of 2018 in order to still produce results by 2020. “Otherwise Germany’s climate policy credibility will be gone completely,” Graichen warns. US President Donald Trump, a prominent sceptic of international climate protection efforts, “would be glad to rub this in our faces at the next G7 summit”, he says. At the last G20 meeting in Hamburg, Chancellor Merkel earned praise by international climate protection advocates for closing the ranks of the group's 19 other members vis-à-vis the current US administration and obtaining a sustained commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement.

But Germany's vanguard reputation becomes increasingly uncertain, given the country's climate protection achievements beyond the diplomatic stage: annual emissions reduction has gradually decreased over recent years, the Agora study explains. [See the CLEW factsheet on Germay's emissions and climate targets] CO2 output fell by an average of 21 million tonnes per year between 1990 and 2000, but the figure came down to just 6 million tonnes between 2010 and 2016. To reach the 2020 goal, emissions would have to shrink by 39 million tonnes each year – “about as much as the entire transport sector emits”, the study says.

Faced with diminishing success of its reduction efforts, Germany introduced a “Climate Action Programme 2020”in 2014 to counter the widening “climate gap”. But the additional measures agreed on for the electricity sector, the transport sector, and energy efficiency failed to bear satisfying results.

The environment ministry (BMUB) conceded in late 2016 that the programme was likely to be less effective than expected. However, it said that emissions in the target year would probably stand somewhere “on the lower boundary” of a reduction between 37 and 40.4 percent.

Combustion engine and coal phase-out as a remedy?

Preliminary calculations published in March by Germany’s Federal Environment Agency (UBA) gave even less reasons for optimism: while emissions in the power sector were falling, very cold weather and increased emissions in the transport sector caused the country’s greenhouse gas output in 2016 to be slightly higher than in the previous year, climbing from 902 million to 906 million tonnes.

Rainer Baake, Germany’s energy state secretary in the economy ministry (BMWi), this week singled out the transport sector as the greatest obstacle for the country to reach its climate targets. Focussing on the 2030 reduction target of 55 percent compared to 1990 levels, Baake urged the government to consider banning new cars with combustion engines by 2030. “What is the alternative?” he asked an audience in Munich.

The proposal had already been made by the Green party, of which state secretary Baake is a member, but so far failed to garner widespread support in the political arena. While many Germans continue to regard climate protection one of the most urgent issues in domestic and international policy, few seem ready to make it a key factor for their voting decision.

Oxfam Germany’s climate expert Jan Kowalzig calls Agora Energiewende’s findings a “shameful record of the government’s climate policy failure”. Kowalzig argues the government was putting the brakes on renewables expansion instead of initiating a necessary phase-out of coal-fired power production. “This is not just about a few percentage points,” he says.

If Germany’s next government was “even only half-interested” in abiding by the Paris Climate Agreement, an ad-hoc climate protection programme had to be accompanied by a coal exit. “The dirtiest plants have to go off the grid quickly and Germany needs to get rid of coal within 15 to 20 years,” Kowalzig argues.

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende is a project funded by Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.