German Greens confident pro-climate government coalition possible

The Greens are determined to make coalition talks a success, even though talks with Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU and the FDP looked challenging, Oliver Krischer, vice chairman of the Greens’ parliamentary group, told the Clean Energy Wire.

“Every one of the parties has committed itself to the aims of the Paris Climate Agreement. That’s a good starting point,” said Krischer, who also served as his party’s climate and energy spokesman.

First exploratory talks on forming a joint government are set to start next week and aspects of the country’s future climate and energy policy are some of the biggest stumbling blocks.

The process of weaning the world’s fourth largest economy off nuclear and fossil energy – the Energiewende – already been going on for decades and will continue under the next government, regardless of which parties take power. However, the make-up of the next government coalition could define the speed and shape of Germany’s energy transition, making the Greens an important player in the upcoming exploratory talks on forming a government coalition.

According to a recent report by think tank Agora Energiewende*, Germany is set to miss its 2020 target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent, compared to 1990, unless the next government immediately steps up its efforts.

Common ground

The Greens’ Krischer pointed to common ground with the pro-business FDP - which he called “the toughest negotiating partner” - that could provide opportunities to advance Germany’s shift to a low carbon future.

“We look at climate protection as something that can foster innovation and strengthen competitiveness, and the parties’ different strengths could turn out to be helpful in this respect,” Krischer said with a view to the FDP campaign focus on innovation.

The economic liberals also called for introducing a CO2 price as a market-based measure to curb carbon emissions, which could serve as another line of compromise between the two parties, according to Krischer.

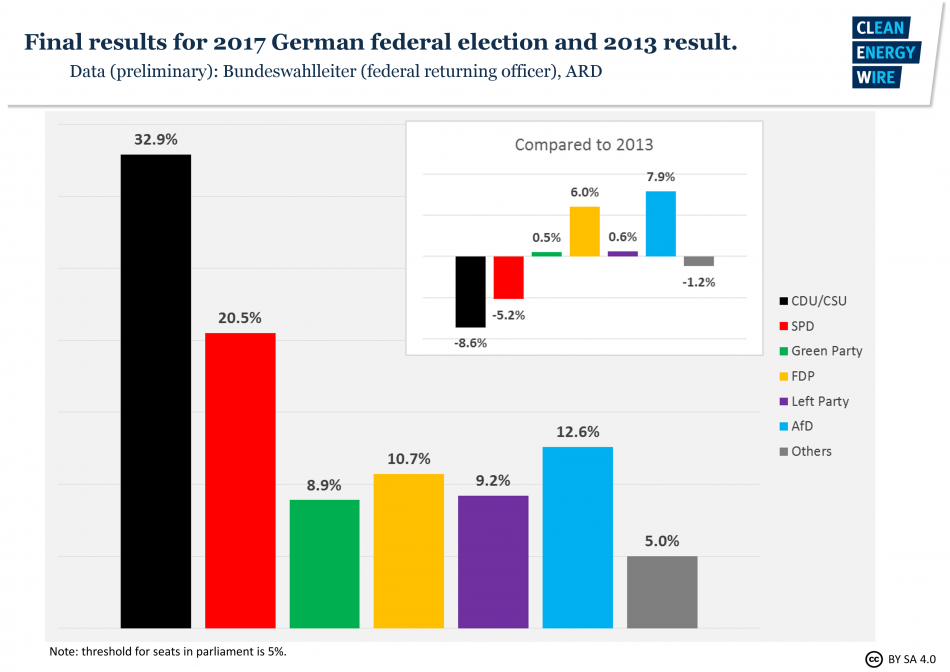

Following September’s general elections, the Green Party could enter the federal government for the first time since 2005, as the smallest partner in a so-called Jamaica coalition, which is dubbed this way since the involved parties’ colours black (CDU/CSU), yellow (FDP), and green mirror the Caribbean country’s flag. The Green Party’s first government participation at the federal level dates back to 1998, in a coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD).

This so-called “Red-Green” government initiated several important climate and energy policies that continue to shape German policy to the present day, such as phasing out nuclear power, and funding renewable energy expansion via the Renewable Energy Act (EEG), emulated in many countries around the world.

A Jamaica coalition is seen as the only viable option after September’s election. Germany’s second largest party, the Social Democrats (SPD), governed together with the conservatives in a so-called grand coalition since 2013. Due to the SPD’s heavy losses in voter support, party leader Martin Schulz on the election night announced the Social Democrats were going to drop out of government and join the opposition. Merkel ruled out to cooperate either with the left-wing Left Party or the right-wing AfD and other constellations fall short of reaching a majority. A Jamaica coalition would have a stable majority and according to recent polls also enjoys backing by a majority of the population.

Difficult partners

In a ‘Jamaica coalition’ the Green Party would find itself at a greater ideological distance from its potential partners than with the SPD as a governmnet partner. “Nobody in the Green Party is particularly excited about a possible Jamaica coalition and other constellations would have been easier for sure,” concedes Oliver Krischer.

In climate and energy policy, the Greens are most likely to clash with the economic liberal FDP, which insists on strengthening market-based policies and heavily criticised the Renewable Energy Act, a cornerstone of Germany’s energy transition stipulating that consumers pay for the renewable roll-out via a surcharge on their power bills.

FDP head Christian Lindner recently reiterated his party’s demand for a “reasonable energy policy” to cut the Energiewende’s costs. On climate policy, Lindner said Germany ought to abolish its “unrealistic” national CO2 reduction targets, and align them instead to the European standards.

The Bavarian branch of the conservatives that share power with Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU at the federal level, the CSU, would also be a difficult partner for the Greens. CSU transport minister Alexander Dobrindt, who would have preferred a coalition with the FDP but without the Greens, recently mocked the environmentalist party as being “the tofu that has fallen into our meat soup.” The Greens have heavily criticised Dobrindt for being too subservient to German carmakers in the ‘dieselgate’ emissions fraud scandal.

“It’s clear that we are not going to support a policy like that of Alexander Dobrindt,” Krischer says. His party wanted to prevent looming driving bans in inner cities as much as anyone, but the carmakers well-being must no longer be placed above people’s health, he argues. “The times of voluntary self-control by the carmakers are over, we need clear rules and authorities that enforce them.”

State-level precedent

A Jamaica coalition would be Germany’s first three-camp government on a national level, but the novel colour combination has already been established at regional state level, in Germany’s northernmost state Schleswig-Holstein.

Green politician Ingrid Nestle, who was directly involved in forging the regional government in June, concedes that the political conditions there are different from those at the federal level, as both the CDU’s and the FDP’s regional branches in the wind power state were much more dedicated to the energy transition than their parties as a whole.

“What was important in Schleswig-Holstein is that all parties were looking for a compromise that supports everyone else’s agenda as much as possible,” the energy economist told the Clean Energy Wire.

The state’s coalition partners did not enter talks with a tit-for-tat approach where a party would have to give up half of its demands to see the other half fulfilled. “It’s possible to fulfil, say, 70 percent of everyone’s wishes. It just depends on the angle you apply to a topic. This often allows everyone to put their mark on a coalition agreement without anyone else losing out.”

According to Nestle, Chancellor Merkel could be an ally of Green climate protection plans. Merkel not only cultivated her image of the “climate chancellor” in the past, but shortly before the election promised that her government would “find ways” to still reach Germany’s 2020 emissions reduction targets.

Coal exit forthcoming?

“The 2020 goals – and actually all the other goals that follow - can only be achieved if a coal exit is initiated now,” Krischer argues. The prominent Green demand of immediately shutting down the country’s 20 dirtiest coal plants, and gradually phasing out coal-fired power production by 2030, therefore had a great chance of becoming a reality if Merkel made good on her promise, he says. A corresponding expansion of renewable energy capacities in that case would become inevitable, he adds.

But Krischer also pointed out that CDU and FDP backed the continued use of coal power for decades to come in their coalition agreement in the coal-mining state of North Rhine-Westphalia earlier this year.

Green politician Ingrid Nestle says that a coal exit is the only way to still reach the 2020 targets and laments that Merkel often showed the right attitude and found the right words on climate “but backs out of important decisions to let others take over.”

“No coalition without climate protection progress”

Krischer concedes that compromises had to be found in all policy areas, but stresses that the Greens will be particularly adamant in climate and energy policy, which also had been the party’s electoral campaign focus and was emphasised in a ’Ten-point plan for Green governance’ published as a supplement to the party’s manifesto. “There will be no coalition agreement without substantial progress in climate protection,” Krischer insists.

“We would be out of our minds if we don’t make climate our chief concern in negotiations,” said Nestle.

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende is a project funded by Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.