Conservative election victory set to narrow climate policy focus in Germany

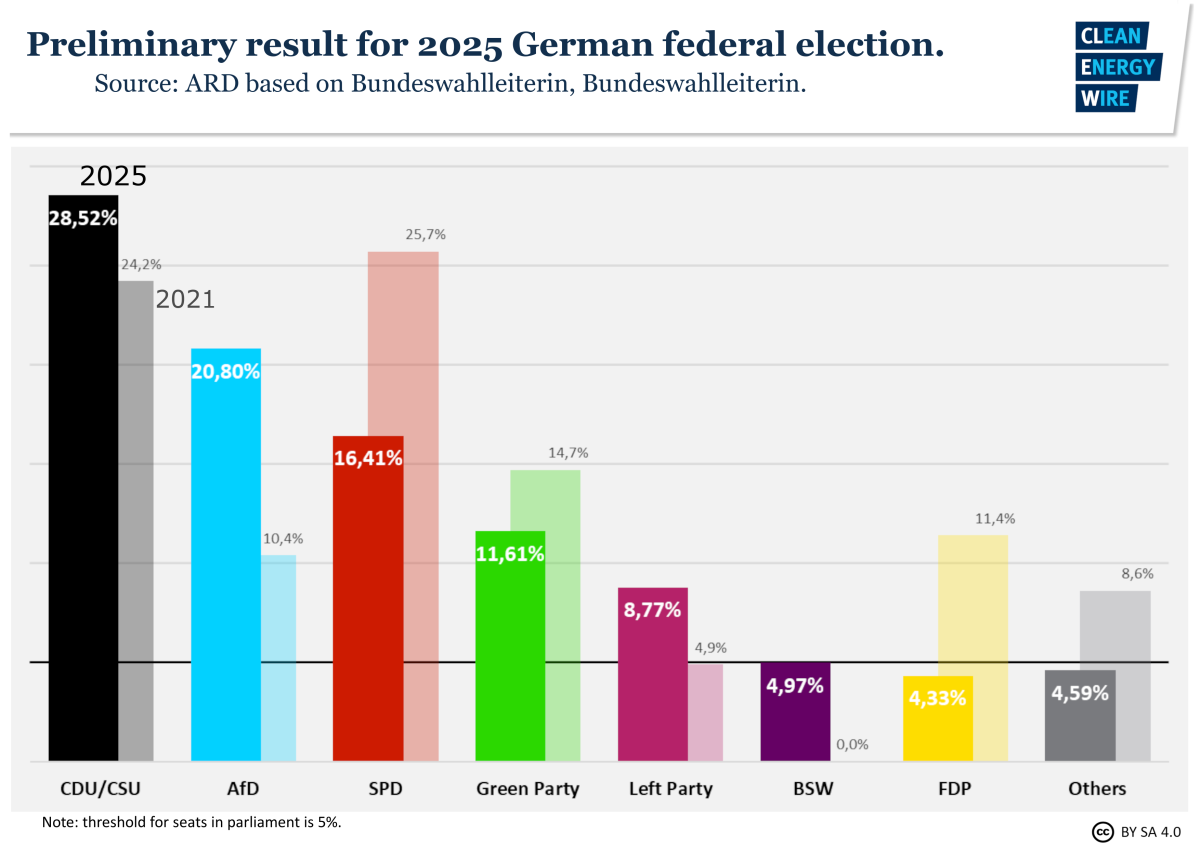

The conservative alliance of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU) under chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz has won the German snap elections and will become the largest party in parliament by a wide margin. However, with first projections by public broadcaster ARD putting the alliance at 28.5 percent, the result remained below average polling figures for the party in recent months, and means Merz will need to form a coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD), and possibly also with the Greens.

The result could mean unprecedented uncertainty regarding the range of possible coalition options, depending on how many parties fail to clear a five percent threshold required to enter parliament – a question that could take a few days to answer due to results being on a knife edge. With up to seven parties in the Bundestag, Germany might face long exploratory talks and subsequent coalition negotiations before a government consisting of either two or three parties can be formed. Previous government formation periods have taken between one month and half a year before a new leadership could be sworn in.

Climate and energy policies in Germany are unlikely to see a substantial shift in key areas under the most likely coalition scenarios. The parties set to form a new government stand by the country’s 2045 climate neutrality target and want to continue the fast expansion of renewable energy sources, as well as decarbonisation in heating, transport and industry. However, the next coalition government’s composition still could have a palpable effect on the speed and ambition with which further energy transition and decarbonisation measures are implemented, and how Germany positions itself in EU climate policy.

Regarding energy and climate policy, conservative chancellor candidate Merz will have to walk a fine line between restart and continuity if he leads the next coalition. The incoming government faces a wide range of urgent challenges in many sectors and reconciling effective climate action with economic stability and affordability for citizens will play an even greater role than it used to.

Major climate and energy policy crunch points in upcoming coalition negotiations

The CDU/CSU alliance has signalled its willingness to enter into coalition talks with both the SPD and the Green Party. These three parties agree on several climate and energy policy issues, including the introduction of a climate bonus, the reduction of grid fees and the buildout of renewables – although they differ in their approaches and ambitions for implementing them.

While there is common ground on many issues, the parties would likely have to find compromises on the following points in particular:

- Oil and gas boiler phase-out: In its election manifesto, the CDU/CSU alliance says it supports low-emission heating solutions independent of technology, and pledges to abolish the contentious "heating law," the outgoing government's legislation that aimed to gradually phase out fossil fuel boilers. However, given that this was an incredibly complex and protracted process, and that the law was passed by a government that included the SPD and the Greens, the parties are unlikely to agree to do away with it. In their respective election manifestos, they instead called for expanding district heating and focusing on municipal heat planning.

- Government borrowing for future investments: The Greens and the SPD both called for a reform to the debt brake – Germany's constitutionally enshrined limit on new government borrowing – to enable future investments. While the CDU/CSU does not rule out a reform, it would like to stick to the debt brake and set strong incentives for private investors.

- Nuclear energy: The CDU says it would like to explore whether Germany's nuclear plants that were last phased out could run again at reasonable technical and financial cost. At the same time, the party is betting on research on nuclear fusion and small modular reactors. The Green Party clearly rejects a return to nuclear energy, as does the SPD.

- Supply chain sustainability: Under the idea of reducing burdens, the CDU called for the abolishment of Germany's supply chain law, which regulates corporate sustainability for respecting human rights in supply chains, and to put a stop to Europe's Taxonomy and Corporate Sustainability Reporting. The SPD, on the other hand, stands by sustainability reporting and the Greens say they would transpose the European rules into national law in an unbureaucratic manner. However, both parties failed to do so during their legislature.

- Earlier coal phase-out: The CDU/CSU would stick to the country’s official coal phase out date of 2038, and party leader Friedrich Merz has ruled out shutting down coal power plants until security of electricity supply is guaranteed (which the Federal Network Agency BNetzA would also ensure). The SPD does not mention this point in its election manifesto, but the Green Party remains committed to not firing coal power plants from 2030 onwards.

- End to combustion engines: The CDU wants to reverse the EU’s 2035 combustion engine phase-out, but the SPD and the Greens oppose this. The Greens have said that phase-out is a precondition for joining coalition - ‘Fossil-fuelled vehicles must be phased out of new registrations after 2035, otherwise [...] the climate protection targets cannot be met,’ Habeck told TV broadcasters RTL/ntv. ”And, of course, we won't go into a government where we can't meet the climate protection targets.”

Amongst other things, it must reconcile industrial decarbonisation and competitiveness, enable a climate-friendly transformation in the heating sector while keeping costs affordable, initiate a serious transport transition against the backdrop of a struggling car industry and tight public finances, and also ramp up investments in climate adaptation and other measures to complement emissions reduction amid the increasing incidence of extreme weather events in Germany and Europe. As election winners, the conservatives are set to approach the Social Democrats (SPD) and possibly also the Green Party for first talks to explore coalition options.

EU partners and businesses call for rapid clarity

The EU and many other partner countries are eagerly awaiting the formation of a new government capable of taking and shaping national and European decisions. At a time when the bloc is facing unprecedented geopolitical challenges as well as continued difficulties with getting economic growth on track again, the collapse of Scholz’s coalition government in November 2024, the very day Donald Trump was re-elected as US president, put a halt to many national policymaking procedures. With its most influential member state entering campaigning mode, the EU was also hamstrung in the past months – and likely will remain so to a certain extent until a new coalition government has been sworn in. Conservative leader Merz said that his aim was to “create a government that is capable of acting as quickly as possible,” adding he hoped to achieve this by late April.

He warned that “the world out there is not waiting for us, nor is it waiting for lengthy coalition talks and negotiations.” However, many of Merz’s decisions as the Conservative’s top candidate during the campaign have been very controversial in the centre-left parties SPD and Greens, which the CDU will likely have to rely on to form a stable coalition government. His momentous step to allow a vote on stricter migration control in parliament together with the far-right AfD, as well as repeated attacks on his possible coalition partners, are unlikely to make talks easy and frictionless.

But German business, researchers and civil society called for a speedy conclusion of coalition negotiations. “In view of the numerous pressing tasks for the continuation of the energy transition and securing a climate-neutral business location, exploratory talks and coalition negotiations must deliver results quickly - also against the backdrop of new European and geopolitical challenges,” said Simone Peter, head of renewable energy federation BEE.

Marc Weissgerber, think tank E3G’s head of Berlin office, also urged a rapid government formation, adding that the target of climate neutrality by 2045 must be “a clear guideline for the new government” irrespective of which parties will be forming it. Internationally, the next government would have to particularly strengthen the EU’s Clean Industrial Deal and strive for a leading role at the next UN climate conference in Brazil to present a sound response to the new US government under Trump, he added.

Climate and energy policy played a major role in break-up of the outgoing coalition government, as the three parties failed to agree on a solution for reconciling investment needs with the country’s debt brake. Many decisions key for reaching binding 2030 climate targets have since remained in limbo, as the collapse left a raft of unfinished policy business. Putting the country on track for its numerous emissions cutting and energy transition ambitions until the end of the decade will be the task of the next government.

Climate change not a major election campaign topic

While the climate crisis was a top issue for many voters in the previous election, it played a much smaller role this time. A survey by public broadcaster ARD showed that the issues driving how Germans vote were domestic security (18% of respondents) and social security (18%), followed by migration (15%) and economic growth (15%). Environment and climate ranked fifth at 13 percent, down from 22 percent at the previous election in 2021.

The SPD under current chancellor Olaf Scholz turned out to be the election’s biggest loser by dropping to 16.4 percent of the vote, its weakest results since WWII. The Green Party, led by current economy minister Robert Habeck, at 12 percent also performed below its expectations. The pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) under leader Christian Lindner, dropped from 11.5 percent in 2021 to 4.6 percent, meaning it will not enter parliament.

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) celebrated a major success at the election: Despite domestic intelligence services monitoring the AfD for suspected extremism, it doubled its 2021 result of 10.3 percent to 20.5 percent. The party’s result is in line with developments in neighbouring countries. Far-right – and often populist – parties enjoy growing support across Europe, and challenge ambitious climate policy. However, as all other leading parties in Germany have ruled out forming a coalition with the anti-migration and climate change-denialist party, it stands very little chance of shaping the next government.

The Left Party also marked a major election success by achieving 8.6 percent of the vote – well above their 2021 result of 4.9 percent. The nationalist-left Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) also performed below its expectations and received 4.9 percent of the vote, which would also mean it will not enter parliament unless figures change once all votes have been counted.

The federal parliament’s opening session has to take place at the latest 30 days after the election, so by 24 March. The German president will ask the outgoing government to continue to carry out official duties until a new administration is sworn in.