'Carrots and sticks' needed to heat homes cleanly — energy analyst

***Please note: This interview is part of a dossier on heating decarbonisation, which also includes the analysis Europe struggles to heat homes without cooking the planet, as well as the factsheets What are the best technologies to heat homes cleanly? , the Q&A - Heating with hydrogen: Clean alternative or pipe dream? and the Q&A – Germany debates phaseout of fossil fuel heating systems***

Clean Energy Wire: What are the best technologies to heat buildings cleanly?

Duncan Gibb: There's no silver bullet technology. When it comes to single-family homes — whether they're new buildings or existing buildings that need some minor renovation — air-to-air and air-to-water heat pumps are a pretty key choice. They have big efficiency advantages. If the pricing policy and financial policies are done right, they can also be very good on cost. They integrate really well with the rest of the energy system, and provide a source of flexibility for the power grid.

Then there's other types of technologies that'll be key too: district heat in urban areas; hot water production with solar thermal; geothermal direct heat feeding into a district heat network or ground source heat pumps in single-family homes. The biggest source of renewable heat right now in Europe is still biomass, so I expect that there will be a role for biomass. I don't think that hydrogen in heating will be used at all.

What can policymakers do to speed up the shift to clean heating?

Policymakers can help provide clarity to the market. This is why I've been supportive in general of the attempts to ban the installation of new gas boilers. Because if you make sure there's enough support provided to the lowest-income households, that it's communicated in a clear fashion and people see what's coming and how to engage with it — that provides a really clear signal to the industry what direction the heating sector is heading in.

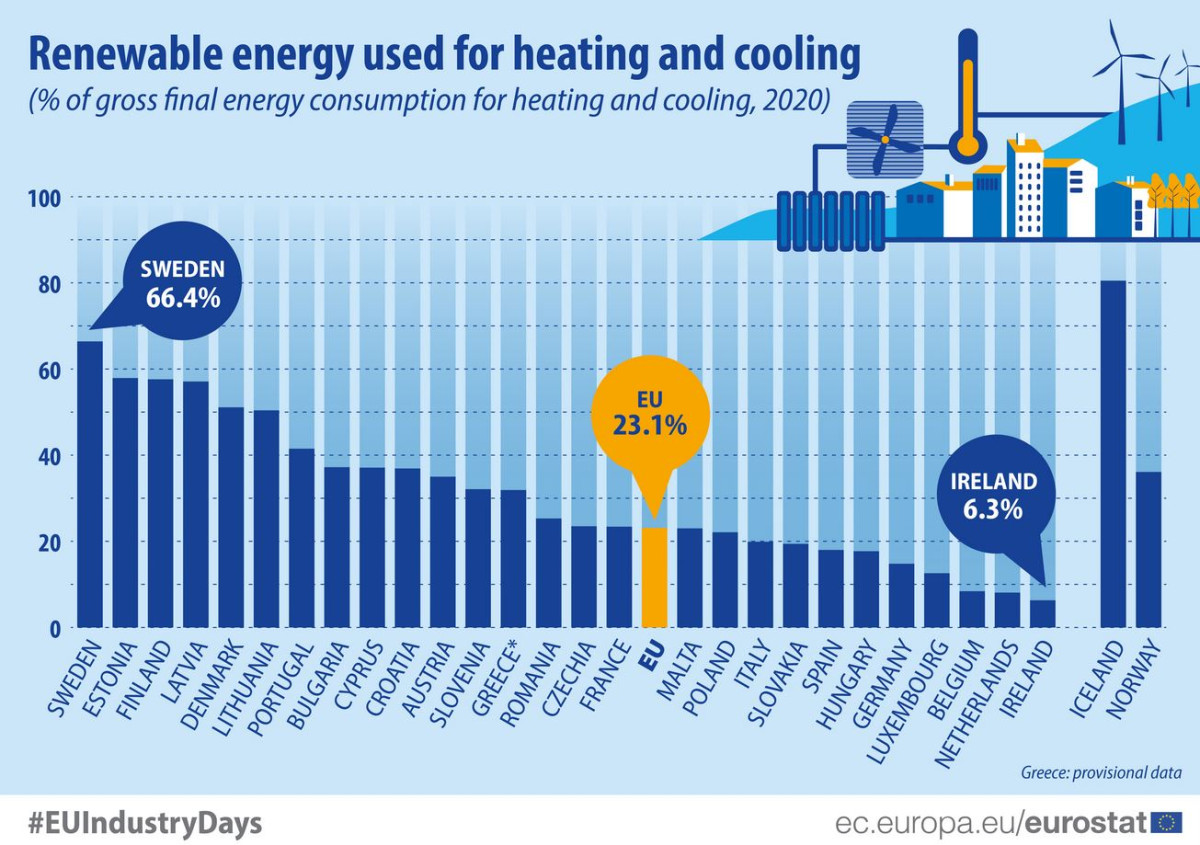

When we look at countries that have successfully really revamped their heating sector and seen big surges in heat pumps, like the Nordic countries, they've been very strong on communication and working with their communities so they understand what's happening. Sweden, for example, spent half its program budget in the 1990s on communications — setting up different stakeholder forums, making sure people were put in touch with installers. Finland made similar efforts and they reaped the benefits because people were less scared of the technology.

Does society need both carrots and sticks when it comes to getting people off fossil heating and onto low-carbon systems?

We definitely do. The effect of providing generous subsidies in certain markets may not be fully effective in completely transforming the market. So in Germany and France, we've seen very generous subsidies in the past years, but the boiler market remains strong. You essentially have a growing heating market. A bigger share is being gradually taken up by alternatives like heat pumps, or solar thermal heating systems, or other clean heating technologies. But it isn't happening at the speed that's necessary. So to me, that's where the stick part comes in.

And you really need both. Because if you only have the stick and you don't have the carrot, then that's when people who don't have the means to make such purchases suffer.

The International Energy Agency said in its net zero emissions scenario not to install any fossil boilers after 2025. Few countries are doing that.

That's the thing about these restrictions: they need courage and vision on behalf of the policymakers. It's more enticing to just make efforts to provide subsidies, because that subsidy is something that most people can get behind. With restrictions, people start to feel like the state is coming into their home. They start to get afraid about the impact on their lifestyle.

I don't think the negative impacts of burning gas in homes is very visceral for a lot of people. They don't see the nitrous oxide emissions, they don't see day-to-day the cumulative greenhouse gas effects, even when there's a massive heat wave ripping through Europe. So I think it takes a lot of courage to do it.

Is there a risk of boilers becoming a culture war issue?

There's a risk with these restrictions on whatever you typically use. We've seen this in the transportation sector, where people have opposed bans on selling internal combustion engine vehicles for the same reasons. It reminds me a little bit of the debate on assault rifles in the US, where you acknowledge this thing is damaging to society but there's a belief that we have a right to choose how I heat my home and the type of vehicle that I drive.

So far, it's been pretty challenging to make the case that there are alternatives. That what you want is a safe and affordable form of transportation. That what you want is your home to be at a nice temperature throughout the year. But there's a lot of industry forces at play as well. And they prey on these fears, they blow them out of proportion. They introduce a lot of misinformation into the mix.

Aside from the misinformation, is there not a valid argument on the cost? The more people swap to heat pumps, the more the people stuck on gas boilers have to pay, because there's fewer people paying the costs for grid infrastructure.

That's a big problem. If you get a lot of single-family homes off gas, the proportion of gas that's being consumed by low-income households rises. There are grid fees that they're going to pay. There's a risk of stranded assets that they might be the ones responsible for if the network fees go up.

And that's why we talk a lot about making sure subsidy schemes are tailored towards low-income households. So not necessarily providing a flat subsidy rate across the board, but having tiered subsidies. France does this quite well, they provide significantly more money for those lowest income households. Germany's been introducing this too. Poland also does this.

Can insulation shield them from some of this?

The ones who benefit the most from their energy costs coming down with greater insulation of their homes — replacing windows, improving radiators — are low-income households. Having targets of renovation for specific branches of income in society could make sense. It tends to be the lowest-income people who live in the worst houses as well as the most leaky buildings. They also tend to underheat.

Insulation is really big too because it also improves the performance of heat pumps. What level of insulation is necessary? It turns out to be not that much. But anytime you can bring down the energy needs of a building, especially for a poor family, it's going to be really important.

What about rich households? If somebody lives in more efficient housing, do they end up consuming more energy in other parts of their lives?

This is called the rebound effect. It has been shown that it does exist. The difference is perhaps in comfort levels. If you happen to be sacrificing comfort level because your home is leaky, then there's a chance with insulation your energy consumption may stay the same because your comfort is improving. But if you already have a high comfort level in your house, then your energy consumption should definitely go down once you insulate.

What lessons can countries in Europe that are lagging behind learn from the success stories?

One thing is that heat pumps work in cold weather. That's a big lesson from the Nordic countries. You hear a lot in Western European countries — from the UK to Germany to France — that once it gets below 5°C, you need to turn on the gas boiler. Or that you need your home to be passive-house standard because if it gets too cold the heat pump can't keep up. And it's just not true. The data we looked at doesn't agree with that and the anecdotal experiences we know of also don't back it up. The fact that you see such a wide breadth and penetration in the Nordic countries, the coldest countries, is evidence of that.

In terms of the other countries that are making quick pace on ramping up their heat pump markets, talking about these tiered subsidies is important. So the Polish market has been generous in subsidies, but they also have a strong regulatory policy to phase out the use of coal for heating. Again, that's the stick that's needed to say, 'we have to stop doing this'.

The other thing that really improves the economic attractiveness of heat pumps is improving the ratio between electricity and gas prices. So making sure that your electricity is not weighed down by taxes and levies that make it super expensive to pay for renewables. Gas is often quite undertaxed. So this requires a delicate touch because you don't want to just make gas more expensive, which would hurt low-income households, but you can rebalance by shifting some of the levees from electricity to gas — which has been done in the Netherlands — or taking levies off the electricity price, like in Germany.

It sounds like the challenge is not really technological, but more just finding ways to transition fairly.

Yes — but there's an industrial challenge too. Demand is exploding for heat pumps across Europe but the supply isn't there yet. And we're seeing prices rise. Some of it is post-covid related, where there's components and parts for manufacturing heat pumps that are not being delivered on time and this cost is being passed along to the installers then to the consumers.

There's a big opportunity for Europe to not repeat the same mistakes that it made with the photovoltaic sector — and allow all that production to take place in Asia — but to make it home grown and manufacture the heat pumps here. Right now, we're seeing pretty serious market bottlenecks, where a lot of people are feeling the push for heat pumps but the prices are still really high because the industry has not caught up yet. They need to train more installers. They need to manufacture more heat pumps. Just throwing subsidy money at the problem is not really solving it.