Who sets the targets? Expert Q&A on European energy and climate policy

Q&A European climate and energy policy: Expert answers

- Who sets European climate targets? - Oliver Geden, SWP

- Every country for itself – Is energy a matter of national policy in the EU? - Nouicer/ Kehoe/ Hancher, FSR

- What really works – which are the key EU policy instruments to drive the energy transition? - Sebastian Oberthür, VUB

- Can Germany decide by itself to build a major new gas pipeline to a third country – such as Nord Stream 2? - Marco Giuli, EPC

- Europe’s power grid – flowing freely across national borders? - Christophe Gence-Creux, ACER

- Can a consumer in Italy buy electricity from a supplier in Denmark? - 1) Maria Schubotz, EPEX Spot / 2) Andreas Jahn, RAP

- What is the EU’s energy and climate policy relationship with other European countries? - Andreas Graf, Agora Energiewende

- What does Brexit mean for European climate and energy policy? - Brendan Moore, University of East Anglia

1. Who sets European climate targets?

Oliver Geden, Senior Fellow at German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), Lead Author for Working Group III & Member of Core Writing Team for Synthesis Report IPCC

"There are different types of climate targets in Europe. The most significant one is the economy-wide GHG emissions reduction target set by the European Union, e.g. 20 percent by 2020 (base year 1990), 40 percent by 2030 (currently 40% compared to 1990, originally set in 2014, to be renegotiated by December 2020) or net zero emissions by 2050 (set in 2019). The 2030 target also forms the core of the EU’s joint Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the UNFCCC.

Traditionally, economy-wide climate targets have been decided by consensus in the European Council, consisting of the now 27 Heads of State and Government. This process makes targets politically but not legally, binding. While the newly introduced ‘EU Climate Law’ will enshrine the EU’s overall ambition, the regulatory focus is on three main legislative pillars, the Emissions Trading Directive (ETS), the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) and the Regulation on Land-use, Land-use change and Forestry (LULUCF). These pillars have their own sub-targets. Once the overarching target is set, the European Commission makes proposals on how to split up the EU’s overall ambition among ETS, ESR and LULUCF. Afterwards, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU (consisting of the 27 environment ministers in this case) renegotiate the detailed rules for ETS, ESR and LULUCF as equal co-legislators, based on (qualified) majority voting.

There are only limited flexibilities between ETS, ESR, and LULUCF. The ETS (covering mainly the power sector and heavy industry) does not include national sub-targets anymore, only a European-wide cap. The ESR (covering mainly transport, buildings and agriculture) is still based on national sub-targets, which are differing widely, with much more stringent targets for wealthier member states. The actual target numbers for ETS and ESR are often confusing since they use 2005 as a base year, not 1990. LULUCF currently works with national ‘no debit’ targets, meant to secure that there will not be more emissions than removals from land-use – but these targets aren’t based on actual emissions/removals, but compared to a set of reference levels for different land-use categories."

2. Every country for itself – Is energy a matter of national policy in the EU?

Athir Nouicer (research associate), Anne-Marie Kehoe (project associate), Leigh Hancher (part-time professor, director of the FSR Energy Union Law Area) at the Florence School of Regulation (FSR), European University Institute

"What could have been a dream only a few decades ago is increasingly becoming a reality; energy markets in Europe are becoming more and more integrated and interdependent physically, economically, and from a regulatory perspective. From a political point of view, the integration followed three main stages, with increasing levels of detail: European treaties, EU legislative energy packages, and detailed market rules that have been developed in the process of creating a harmonised and interconnected energy system in Europe.

From the founding Treaty of Rome in 1957 to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) in 2009, European treaties have sought to create and advance a common market and eliminate trade barriers between Member States. In energy, the legislative packages have focused on establishing and refining common rules for the internal market. Since 2015, the EU has been cultivating an Energy Union, which seeks to build energy security and solidarity, a fully integrated internal market, support research and competitiveness, and accelerate energy efficiency and climate action toward the goal of carbon neutral EU economy by 2050. The core purpose of this is to provide EU consumers with secure, sustainable, competitive, and affordable energy. Inevitably, with increasing integration, we are met with the debate as to the sovereignty of Member States in the face of these EU-wide manoeuvres and the equity of the legal obligations being imposed on Member States by the EU. Where should the line be drawn? Given the urgency of the climate crisis and its transboundary nature, it has become increasingly evident that energy can no longer be considered exclusively a national issue.

EU states determine their own energy mix, but it can no longer be considered exclusively a national issue. Find out more

The legal basis for EU measures is provided for in Art. 194 TFEU. Art. 194(2) enshrines the right of Member States to determine their own energy mix, limiting the EU’s powers. These rights are especially relevant with the prospect of carbon neutrality in sight and the (non-)binding renewable energy targets at national level currently in place for 2030. To what extent should the demands of the energy transition be left in the hands of Member States? And what happens when Member States fail to match the EU’s ambition? It is worth keeping in mind that, while the obligations of Member States toward the 2030 targets are non-binding at national level, several other paths are opening up which could offer alternative ways of enforcing action. Among these, is the principle of solidarity, provided in Art 194 TFEU, which has recently been given legal significance. If used, this notion could potentially infringe upon the freedoms of Member States if their actions are deemed contrary to the wider good of the Union members. Another potential route is the different legal basis for environmental legislation (Arts 191-193 TFEU), which offers a path toward pan-European action, as recently seen with the EU Climate Law proposal. Additionally, separate from EU intervention, private enforcement of energy and climate action is increasingly gaining traction in the EU. But is this the best way forward?

Perhaps we should reformulate what is being asked. Could the Member States sufficiently achieve the necessary integration and policy objectives by themselves? Technically, no one knows, but the Commission impact assessment on market design accompanying the proposals of the EU Clean Energy Package states several reasons justifying the necessity of EU action. For instance, on security of supply and cross-border issues, the Member States do not look beyond their territories when developing plans to safeguard against an electricity crisis. Uncoordinated approaches at the Member State level would lead to the adoption of suboptimal measures and exacerbate the impacts of a crisis. This entails serious risks for the security of supply. In the framework of the interconnected electricity system, the risk of a blackout is not limited to national boundaries. The Italian blackout of 28 September 2003 that also affected some parts of Switzerland shows how limited the regulator’s powers were to coordinate international relations. Cooperation allows Member States to pool resources, play into their strengths and bridge the gaps in their energy system in a harmonised and cost-efficient manner. Furthermore, in terms of energy and climate action toward climate neutrality, what would happen in the face of inaction on the part of a Member State without a common policy and legislative framework? How could a ‘just’ transition be reached if Member States are left to their own devices – and fail to contribute?

A compromise between EU intervention and preserving the autonomy of Member States

The Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action, which is part of the Clean Energy for all Europeans Package, is the first attempt to introduce an integrated governance mechanism for the Energy Union. The governance mechanism needed to ensure an adequate response from Member States toward reaching the targets and, indirectly, create a degree of accountability amid growing anti-EU sentiment. While the non-binding nature of the targets at national level does leave energy and climate action vulnerable to the winds of national politics, the approach of the regulation offers an interesting counterpoint to the standard form of governance. The regulation, which is a compromise between EU intervention and preserving the autonomy of Member States, opens a new path in the governance of EU energy and climate. In taking a more interactive, dialogue-based approach to governance, it has shifted the focus away from a more punitive view of EU governance toward positive enforcement. In a rapidly and continually evolving sector in which the priority is now firmly on decarbonisation and a complete overhaul of our energy system, this bottom-up approach to governance recognises that a true transformation of the system requires all hands on deck."

3. What really works – which are the key EU policy instruments to drive the energy transition?

Sebastian Oberthür, Research Professor Environment & Sustainable Development, Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, and University of Eastern Finland

"The EU has adopted a growing set of policy instruments to drive the energy transition – a process that is ongoing. The whole policy set-up is currently under review in the framework of the European Green Deal launched by the European Commission in 2019 to make the EU fully sustainable and climate-neutral by 2050.

Six legislative instruments can be considered key. First, the Union-wide Emissions Trading System (ETS) limits and reduces the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of large industrial installations and power stations across the EU. Second, an Effort-Sharing Regulation defines obligations for each member state to reduce GHG emissions in the other, non-ETS sectors (transport, buildings, agriculture). Third, the Renewable Energy Directive aims to increase the share of renewable sources of energy in total EU energy consumption to 32 percent by 2030 (up from a 2020 target of 20%). Fourth, the Energy Efficiency Directive pursues an improvement of energy efficiency of 32.5 percent by 2030 (also up from 20% for 2020). Fifth, a regulation added in 2018 seeks to ensure that land and forests are managed in order to maximise their contribution to climate protection. Sixth and finally, a new Governance Regulation adds a process of planning, reporting and review to ensure that each member state establishes, regularly updates, and implements national climate and energy policies and measures in line with the EU-wide objectives.

Together, the ETS and the effort sharing ensure that the EU reduces its GHG emissions by at least 40 percent by 2030 (compared to 1990). The other instruments ensure that EU member states pursue crucial policy and structural changes required to (over-)achieve these emission reductions and advance the energy transition also beyond 2030.

Various further policy instruments pursue similar change in more specific areas, such as the energy performance of buildings, the CO₂ emissions of cars, the energy consumption of specific products (such as fridges and vacuum cleaners) and the electricity market.

A proposal for a new Climate Law currently in the legislative process aims to make the 2050 climate-neutrality objective binding and to increase the GHG emission reduction target for 2030 to at least 55 percent. A suite of further proposals for strengthening the existing key instruments accordingly are expected for June 2021."

4. Can Germany decide by itself to build a major new gas pipeline to a third country – such as Nord Stream 2?

Marco Giuli, Associate Policy Analyst at the European Policy Centre, and PhD researcher at Institute of European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

"Germany – like all other EU member states – can decide unilaterally to build new gas pipelines to third countries, including Nord Stream 2. According to the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, states remain sovereign as per the choice of their energy mix and energy connections with third countries. While this principle is undisputed, the legal quarrel around Nord Stream 2 has focussed on the extent to which the EU regulatory regime applies to the pipeline. The operational regime foreseen for Nord Stream 2 by its owners and promoters is not compatible with the EU law that requires a separation between ownership and operations and access to third parties.

While EU law clearly applies within the EU territory, most offshore pipelines which bring gas into Europe have not been made subject to EU rules. Under the stated intention to clarify the legal regime for Nord Stream 2 operations, the EU in 2019 extended the coverage of its legislation to pipelines to third countries. Such an extension would apply to the EU territorial waters, but not to the exclusive economic zones, where the largest portion of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline runs.

As a result, uncertainty continues regarding what regime will finally regulate the pipeline’s operations."

5. Europe’s power grid – flowing freely across national borders?

Christophe Gence-Creux, Head of Electricity at European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER)

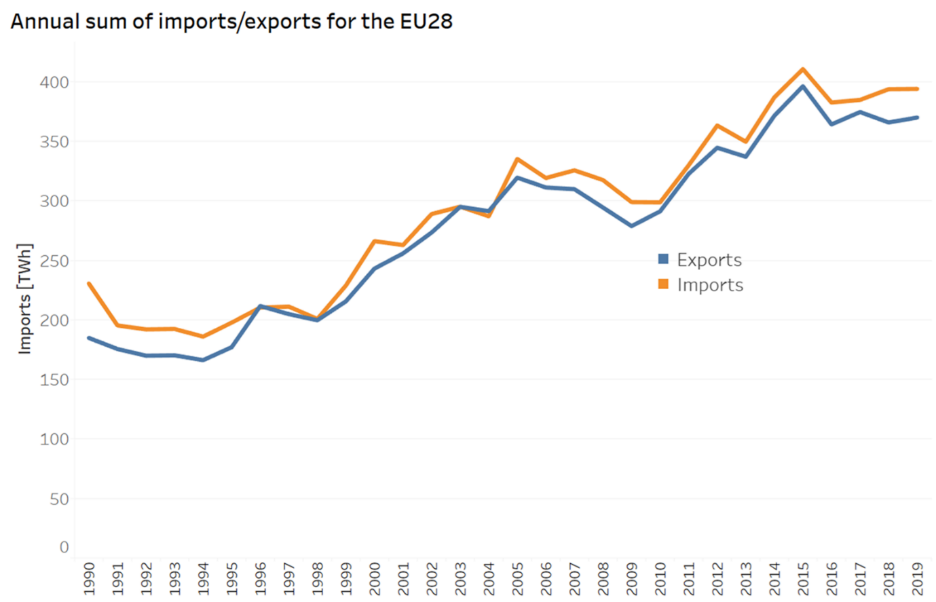

"The steady increase of cross-border exchange in Europe over the past 30 years (see figure below) shows that the European electricity sector is more and more integrated. This is the result of a collective and unprecedented effort to develop and implement harmonised binding rules at EU level (the Network Code Implementation Process), which contributed to establishing a more competitive, sustainable and secure internal electricity market. Full integration of EU national markets could deliver savings of up to 40 billion euros per year by 2030 to consumers.(1)

A lot of progress has been made but a great deal remains to be done. With the Clean Energy for all Europeans Package, the European co-legislators strived to tackle the problem of discrimination between internal versus cross-border trade (see the Agency’s Recommendation on the subject for more details), one of the most significant barriers for the integration and the efficient functioning of the internal electricity market.

The establishment of an ambitious binding target of 70 percent (at the moment it is close to 30%) on the level of cross-border capacities to be made available to the market at the latest by the end of 2025 represents a very significant step for most of the Alternating Current (AC) borders in Europe.(2) If implemented, it could trigger an important paradigm shift to move towards a more efficient market design and governance framework.

1 According to a study commissioned by the European Commission, the integration of electricity national markets, once completed, could deliver benefits in the range of 12.5 billion to 40bn euros per year by 2030 to EU energy consumers.

2 The average level of transmission capacity currently made available is estimated on average to be close to 30 percent (see the Electricity Wholesale Chapter of the 2019 Market Monitoring Report)."

Press contact: David Merino, Communications Officer, David.MERINO@acer.europa.eu, Tel: +386 8 2053 417

6. Can a consumer in Italy buy electricity from a supplier in Denmark?

The reply to this question is split in two: Maria Schubotz (EPEX Spot) focusses on the wholesale market, while Andreas Jahn (RAP) takes a closer look at end or retail customers.

1) Maria Schubotz, Senior External Communications Officer at EPEX Spot, part of EEX Group

"For the wholesale consumer, the answer is yes.

On the electricity wholesale market a consumer in Italy can buy electricity from a supplier in Denmark. This is possible thanks to a mechanism called Market Coupling. Market Coupling is a result of the close cooperation between Transmission System Operators and Power Exchanges. Market participants anonymously submit orders to buy or sell electricity with their Power Exchange. The Power Exchange will then calculate the market price based on offer and demand. All electricity traded on the short-term markets is delivered physically. During the price calculation, Power Exchanges take into account the available transmission capacity at the European borders, which was communicated to them by TSOs.

At the moment of price calculation, Market Coupling determines the electricity flows at the borders in a way that maximises social welfare and that is most efficient – meaning flows will go from a lower priced area to a higher priced area. Therefore, electricity flows can lead from Denmark to Italy, or from Spain to Finland, and so on. The market participants involved in the transaction, however, will not know where the electricity comes from, as the markets are anonymous. The Internal Energy Market is one of the biggest achievements of the European Union. As of today, European Market Coupling covers 27 countries, with more to follow.

The European short-term power market is anonymous, provides fair access and includes all electricity generation modes, from nuclear power to solar generation. As buy and sell orders are processed anonymously, it is not possible to trace the amount of renewable energies traded at the market. Developments show, however, a rising success of trading products that are tailored to the needs of renewable generation. This proves that an increasing amount of renewables is integrated into the system thanks to the efficiency of European short-term power markets. To trace renewable generation, market participants additionally have the possibility to use Guarantees of Origin.

Press contact: press@epexspot.com

The European Power Exchange EPEX SPOT SE and its affiliates operate physical short-term electricity markets in Central Western Europe, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. As part of EEX Group, a group of companies serving international commodity markets, EPEX SPOT is committed to the creation of a pan-European power market."

2) Andreas Jahn, senior associate at the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP)

“Can end consumers in Italy buy electricity from Denmark? Yes, if a supplier offers it on the Italian market.

The European electricity market is organised such a way that the supplier must come to the customer. An Italian customer is permitted to purchase from a Danish supplier. However, the Danish supplier must comply with the Italian conditions, such as concluding a grid usage contract with the local grid operator, paying the local fees and taxes, and taking into account the Italian consumer protection standards. It’s this last point in particular that benefits consumers, who can receive the contract offer in their own language and compare it with their local standards.

The supplier buys the electricity on the local energy trading exchange, meaning that the electricity is generated where it is consumed. This is in part because of the decentralised way European power lines are used [market coupling - see reply by EPEX Spot]. This process rules out economically inefficient procurement and payment of interconnection and transmission capacities by individual market participants. Physically, the electricity does not follow the path of the trading contracts; it is delivered to the consumer from the nearest source of generation.

If the buyer cares about the environmental quality and geographical origin of the electricity, in our example from a Danish wind turbine, the electricity can be supplied throughout Europe via the separately traded green electricity characteristics (guarantees of origin). The wind turbine operator essentially provides a document that she produced a certain amount of kilowatt hours and sold these to the supplier in Italy. The supplier may sell this power and advertise it as Danish wind power, even though the actual electricity consumed is generated from an unknown source locally. The guarantees of origin principle applies in the EU, but also in neighbouring or associated countries, such as Switzerland and Norway.”

7. What is the EU’s energy and climate policy relationship with other European countries?

Andreas Graf, Project Manager EU Energy Policy at think tank Agora Energiewende

"According to the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has a number of exclusive competences that are relevant for relations with third countries, including on setting customs duties and trade policy, as well as on establishing competition rules for the internal market. Where the EU has exclusive competences, the Commission can negotiate and the Council can conclude international agreements with third countries. Where it has shared responsibility with member states, international agreements must also be ratified by member states. The demarcation between these two cases is often not clear, meaning the representation of the European Union can differ depending on the topic. Negotiations are also conducted by a negotiator or negotiating team nominated by the Council (e.g. Michel Barnier for Brexit), not necessarily by the Commission.

Representation role of different actors in the EU external sphere

|

Representation |

Exclusive competence |

Shared competence |

Common Foreign and Security Policy |

|

Commission |

X |

X (For EU competences) |

|

|

High Representative |

|

|

X |

|

European Council |

|

|

X |

|

EU Council |

|

X (For MS competences) |

|

Source: Based on Szapiro, M. (2013): The European Commission: A Practical Guide.

In this context, the EU member states have established a special relationship with some non-EU countries in Europe. This most clearly applies to the European Economic Area (EEA), which is an international agreement that links the EU member states and three European Free Trade Association (EFTA) states (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway), giving them access to the EU single market.

The UK currently also benefits from this relationship during the transition period for its exit from the European Union ending 31 December 2020. Members of the EEA adopt most EU legislation concerning the single market with the exception of fisheries and agriculture. For example, the EEA countries are also members of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). The EU also has special bilateral relationship with Switzerland and San Marino. Since 1 January 2020 the EU ETS is also linked with the Emissions Trading System of Switzerland.

Last but not least, the EU is in accession negotiations with several countries (Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey) concerning potential membership in an enlarged EU. Any country that joins must implement EU legislation that applies to all member states. For example, before becoming an EU Member State in 2013, Croatia was included in the EU ETS."

8. What does Brexit mean for European climate and energy policy?

Brendan Moore is a senior research associate at the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations (CAST) and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in the School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia

"Brexit will have important but uncertain impacts on European climate and energy policy at three levels: EU policy, international climate negotiations, and UK domestic policy. First, when the UK left the EU at the end of January 2020, it immediately lost its representation in the EU institutions just as the Union had begun to embark on policy changes under the European Green Deal. The UK's absence will be more strongly felt in the Council of Ministers – where the government was a relatively united and effective advocate for stronger greenhouse gas reduction targets but an opponent of mandatory renewables targets. In the Parliament, the UK delegation was fragmented in relation to climate policy because of the widely diverging positions of parties such as UKIP, Labour, and the Conservatives, diminishing the impact of their departure. Overall, EU climate policy is complex and evolving, and UK policy positions differed by topic, meaning that the full impact is difficult to predict.

Second, EU-UK cooperation in international climate negotiations is evolving and uncertain. Both parties have pledged continued ambition in this area, but there are concerns about the EU losing the UK's diplomatic capacity and resources, and on how much the UK will lose influence outside of the bloc.

Third and finally, Brexit will impact UK domestic climate policy outside of the EU's environmental law and enforcement mechanisms. The UK must replace these governance arrangements while implementing the policies needed to implement its ambitious climate goals and negotiating with the EU on level playing field commitments in any free trade agreement.

In conclusion, both the EU, UK and international approaches to climate governance are complex, multi-level and interact with each other. Brexit will have an impact on all of these levels, but their very complexity means that there is significant uncertainty about what this means for avoiding dangerous climate change."