CLEW Guide – Snap elections add new uncertainties to Germany's 2030 climate targets

With its “CLEW Guide” series, the Clean Energy Wire newsroom and contributors from across Europe are providing journalists with a bird's-eye view of the climate-friendly transition from key countries and the bloc as a whole. You can also sign up to the weekly newsletter here to receive our "Dispatch from..." – weekly updates from Germany, France, Italy, Croatia, Poland and the EU on the need-to-know about the continent’s move to climate neutrality.

***Please note: We will do a thorough update of this factsheet once Germany's next government has been sworn in in early May. To keep up with the latest, find all our election coverage here or follow this tracker.***

Content:

Key background

- As Europe’s largest economy, Germany is a key energy hub in the heart of the continent.

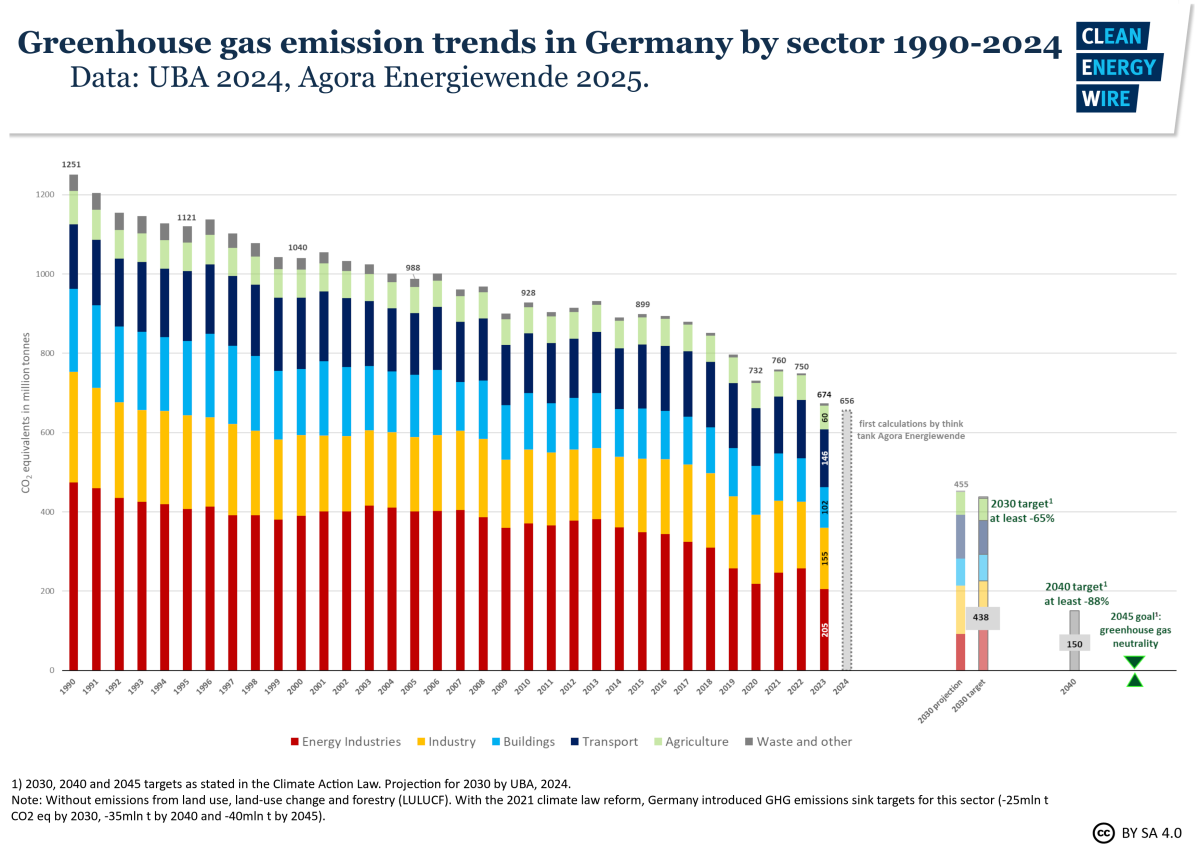

- Greenhouse gas emissions have decreased 48 percent since 1990 and Germany aims for climate neutrality by 2045.

- Germany’s trademark “Energiewende” – the country’s transition to climate neutral and nuclear-free energy supply – has broad public backing.

- Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s three-party coalition of SPD, Greens and FDP fell apart over budget controversies, which also included disagreements over the right way forward for the country’s energy transition. German voters head to the polls on 23 February 2025 for a snap election, against the backdrop of a flagging economy, the war in Ukraine, and the second Trump presidency in the U.S. The break-up leaves the country with a host of unfinished policy proposals that risk grinding to a halt until a new government is sworn in. [CLEW is continuously tracking the most recent developments on the road to snap elections in this overview]

- According to recent polls, the leader of the opposition Conservative CDU/CSU alliance, Friedrich Merz, has the best chances to succeed the unpopular Scholz as chancellor. Merz’s Conservatives have often sharply criticised the government’s energy and climate policies in recent years, suggesting that certain priorities are set to change under a new government. However, the fundamentals of the country’s landmark energy transition are highly unlikely to change, as they enjoy cross-party support.

- Huge gains by populist parties that oppose the government's fundamental climate and energy positions in three state elections in eastern Germany over the summer cast a shadow over the progress of the country’s energy transition, and the upcoming snap elections. Parties are bracing themselves for a difficult election campaign as far-right and pro-Russia populist politicians stand to benefit from the increasingly politicised climate debates. [Find more background in this factsheet on East Germany and the energy transition and our deep dive into the impact of the rise of populists in power].

- While still intact, the coalition presented a comprehensive Climate Action Programme in 2023 to put the country on track towards reaching its climate targets. However, months-long disputes on key climate policies – such as the phase-out of new oil and gas heaters – have held up progress.

- Projections by the country's Federal Environment Agency (UBA) showed that the country is on track towards achieving its 2030 climate targets for the first time, not least thanks to the resolute expansion of renewable energy sources.

- Germany continues to struggle with high emissions, especially in the transport and buildings sectors. Moreover, demand for electric cars is sluggish, with carmaker Volkswagen preparing layoffs at production sites as sales of EVs slump. The current government target of putting 15 million electric cars on the road by 2030 increasingly looks difficult to reach, and observers are expecting the country to miss it by up to five years. Car manufacturers are also slowing down or scaling back plans to switch their production towards EVs.

Major transition stories

- Government without a budget – Germany’s coalition collapsed over budget controversies almost exactly one year after a constitutional court ruling on Germany's so-called debt brake that declared tens of billions of euros earmarked for climate and transition projects as unlawfully booked. Provisional spending takes effect until a new government is sworn in and decides a budget, which might take as long as mid-2025. This spells months of uncertainty for Germany’s industry, and many other climate and energy plans.

- Economic woes – Germany’s political upheaval is playing out against the backdrop of growing concern about the economy as a whole, fuelled by an ongoing decline of manufacturing activity, a weakening labour market, and mounting worries about the future of the country’s carmakers in particular. VW, the country’s largest private employer, aims to cut 35,000 jobs by 2030.

- Country on track to reaching national 2030 climate target – Germany is largely on track to reaching its national target to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 65 percent by 2030, according to projections by the country's Federal Environment Agency (UBA). However, the projections overestimated the amount of emissions which would be cut in the coming years, said the Council of Experts on Climate Change, which blamed the misjudgement on climate budget cuts and outdated assumptions about gas and CO2 allowance prices. Germany also still looks set to also fail its EU goal for sectors such as transport, buildings and agriculture.

- Climate foreign policy – Germany is seen as a credible leader in international climate talks despite shortcomings at home, and has hosted the annual Petersberg Climate Dialogue for more than a decade. The government published a climate foreign policy strategy set to ensure all government ministries speak with one voice to international partners to foster a socially just and economically successful move to climate neutrality worldwide. The strategy accompanies the security policy strategy and a China strategy, both published in 2023.

- Just transition – What started out with a debate about supporting coal workers in mining regions and state subsidies for so-called “structural change” is increasingly turning into a cross-societal debate about leaving no one behind in the transition to climate neutrality. Installing a heat pump, buying an electric car or dealing with higher fuel costs due to CO2 pricing affects everyone, but low-income households will need more support to manage the changes. A just transition will become a big issue not only in Germany, but across Europe, when the new EU emissions trading system for transport and buildings starts in 2027. The "climate bonus," which the government promised in its coalition agreement and which would return some of the revenue from Germany's carbon pricing to low-income citizens, will not be delivered in this legislative period.

- Sustainable finance – In contrast to its reputation as an energy transition pioneer, Germany has been a latecomer in tapping into the potential of compelling banks, insurance companies, fund managers and other financial actors to curtail CO2-intensive projects and fund cleaner alternatives. The German government coalition under chancellor Scholz has vowed to quickly expand the country's role in the transition to green and sustainable investment practices and fully integrate the financial sector in its climate policies.

- Adaptation – The latest climate change monitoring report urged Germany to step up its efforts to adapt to the already unavoidable effects of climate change. The country faces a multitude of negative impacts, including prolonged droughts, severe water loss, floods, and increasing temperatures. The government has passed a law making it legally binding to draw up climate risk assessments and implement adaptation measures. It presented the accompanying Climate Adaptation Strategy which, for the first time, contains measurable targets and measures to increase preparedness. In addition, the government presented a water strategy and a natural climate action strategy.

- Carbon removal – Another key project on hold is the government’s long-term strategy for negative emissions, which was meant to introduce a 2060 target for net-negative greenhouse gas emissions and intermediate targets for technical carbon sinks. The strategy, of which the government released a first outline, was meant to look at different methods to capture, remove, store and use carbon dioxide and consider economic incentives to help ramp up the corresponding industrial infrastructure.

- Supply security – The crucial Power Plant Security Act will not be adopted before the election. The law is supposed to prepare auctions for Germany’s planned fleet of hydrogen-ready gas plants, which will be needed to stabilise the energy system amid its transition to 100 percent renewable energy sources. Germany’s electricity system remains one of the most reliable in the world amid the expansion of wind and solar, despite the nuclear exit and the fallout from the energy crisis in 2023.

- Climate protests – Following the large success of youth protests led by the Fridays for Future movement since 2018, which helped convince large parts of society that ambitious action is needed, more drastic forms of protests such as activists gluing themselves to streets or throwing paint at art works and landmarks such as the Brandenburg Gate provoked mainly negative reactions. Faced with dwindling numbers of participants, Fridays for Future has begun teaming up with other interest groups in society and launched a protest for better public transport funding together with labour union Verdi, which represents workers in the sector. The “Last Generation” (Letzte Generation) group has said it is dropping its name and will change its tactics by focusing on social issues related to climate change.

- Raw materials and recycling – The energy crisis fuelled by Russia’s war against Ukraine has pushed the dependence on imports of key raw materials high on the subjects for debate in Germany and Europe. The government presented a draft circular economy strategy, and has adopted its China strategy. The EU also presented a Raw Materials Act to ensure the union has access to critical materials needed for energy transition technologies.

- 'Franco-German engine' – The European Union faces a multitude of parallel challenges that share the question of how and where it sources its energy in the future. From the increasing urgency to act on emissions reduction over security risks raised by Russia's war on Ukraine to economic stability in a world of rapid industrial change, the two core EU members France and Germany must come clean on the bloc's energy strategy to make it fit for the tasks ahead, but headlines have been dominated by division over the role of nuclear plants, renewables and combustion engines. The election of Donald Trump as U.S. president could help boost cooperation.

- Skills shortage – Major roadblocks on the path to climate neutrality include a lack of skilled workers to implement renewable energy expansion plans and energy efficiency projects, as well as grid expansion. The government has reformed immigration laws with the aim of filling tens of thousands of vacant energy transition jobs.

Sector overview

Energy

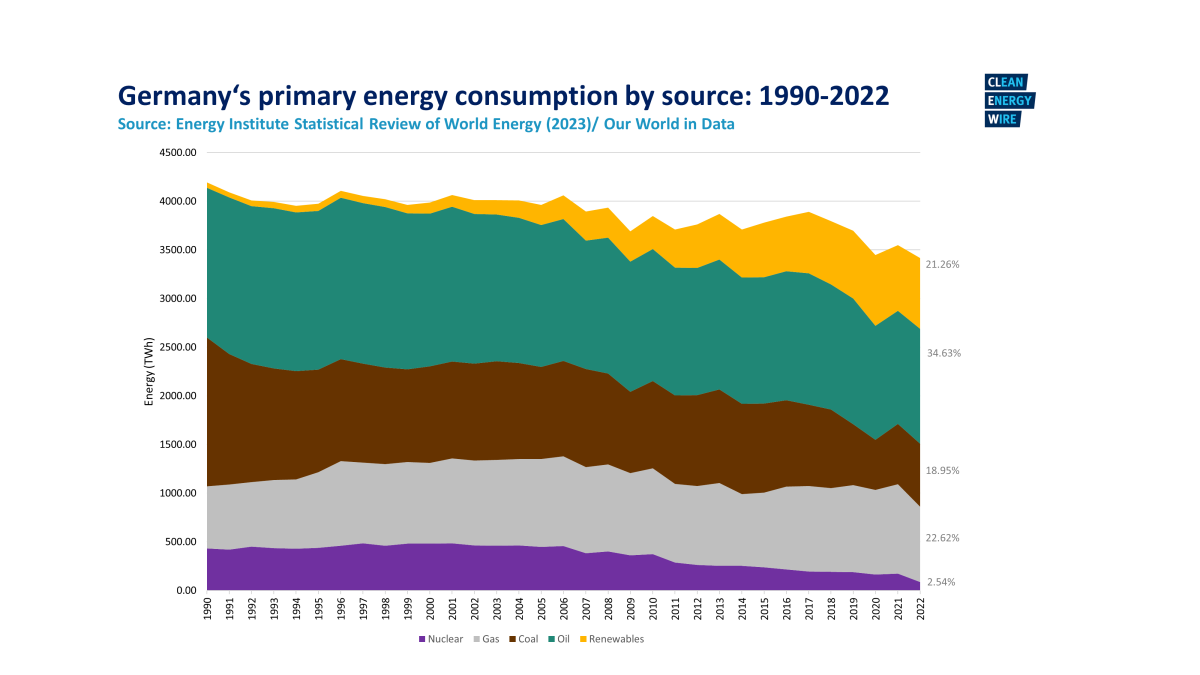

- The sector is responsible for roughly 30 percent of total GHG emissions.

- The last nuclear power plants were shut down in April 2023, completing a decades-long phase-out process. The government wants to pull forward the coal exit “ideally” to 2030 (from 2038), and there are no phase-out targets for oil and gas.

- Citizens’ wind and solar projects helped ignite a shift to renewables that raised the share in the power mix of wind turbines, solar panels and other renewable technologies from 4 percent in 1990 to 55 percent in 2024 (2030 target: 80 percent).

- Germany plans a massive expansion of renewables over the coming decade, but also to build additional (hydrogen-ready) gas power plants as a supplement to intermittent wind and solar electricity. Industry leaders have warned that government tenders for these plants must come soon to enable an early coal phase-out by 2030, but a decision was postponed until the next government takes office in 2025. While wind power expansion is picking up, it is still off the 2030 target path. The solar sector is more clearly on an upward trend.

- However, oil, gas and coal are still very important energy sources, for example in transport and heating: the share of renewables in total energy consumption reached 20 percent in 2024.

- The energy crisis fuelled by Russia’s war on Ukraine forced a huge shift in energy supply and potentially helped speed up the energy transition, but led to a domestic LNG buildout.

Industry

- The sector is responsible for 23 percent of total GHG emissions; most industry emissions are covered under the EU ETS.

- Germany is set on transforming its world-renowned industry (e.g. steel, chemicals, cement) to make it fit for a climate-neutral world and to host the industrial production of the future. The government agreed on a package of measures worth billions of euros in 2024 alone to boost the international competitiveness of its prized heavy industry.

- However, things are set to change. Researchers say it is unrealistic to carry out all energy-intensive production steps for green raw materials in Germany in the future, mainly because renewable electricity generation will be much cheaper elsewhere. The country should focus on further processing in the steel and chemical industries and in the downstream sectors of the economy.

- Industry support measures include a “pioneering” scheme to assist industry in transitioning away from fossil fuels through auctions. The so-called “climate contracts”could inject dozens of billions of euros in subsidies into helping to make the production of steel, cement, chemicals and other materials climate neutral.

- After a long period of resistance, companies are fully taking on the challenge and see business opportunities in the global race to net-zero industry.

- Green hydrogen is seen as key to decarbonising industrial processes. Germany aims to become a global technology leader and has laid down plans in its national hydrogen strategy. The government has also published a hydrogen import strategy, as the country will largely have to import the green fuel from abroad due to unfavourable local conditions for renewable electricity production.

Buildings

- Buildings are responsible for 15 percent of total GHG emissions, mostly through heating and cooling with fossil fuels (only direct emissions; excludes emissions from electricity use, district heating, industrial buildings).

- 2024: 56 percent of German homes heated with gas, 17 percent with oil, 16 percent with district heating.

- The buildings sector has failed to meet its annual emission reduction targets since 2020.

- The government’s goals include no more fossil fuel heating systems by 2045 at the latest; the step-by-step de facto ban on new fossil heating systems; and 500,000 newly installed heat pumps per year from 2024. Sales of low-carbon heat pumps grew considerably in 2023, but collapsed in 2024, widely missing the target. This was due in large parts to uncertainty caused by the controversial debate around a law phase out fossil fuel heating.

- Germany is faced with a stagnation of the rate of energy-efficient refurbishment of the existing building stock, although the pace has picked up. Final energy demand of residential buildings has risen in recent years. Confronted with a crisis in the construction sector and a housing shortage, the government decided to suspend the tightening of new building efficiency rules initially planned for 2025.

- The government has introduced a subsidy programme worth billions of euros for the installation of climate-friendly heating systems.

- The government introduced a law to oblige communities to come up with municipal heat planning. It aims to fund the expansion and decarbonisation of district heating (still mostly gas and coal-fuelled).

Mobility

- The sector is responsible for nearly 22 percent of total GHG emissions.

- Transport has been dubbed the “problem child” of the transition, as emissions are falling much slower than in other sectors. Transport has also repeatedly failed its annual climate target, and the government failed to deliver proposals to get it back on track.

- Car-country Germany has many policies that support the use of passenger cars, including no general motorway speed limit, and still often tries to accommodate the needs of the country's car makers, which have invested in expensive, high-end combustion engine models like ever bigger SUVs.

- Germany is aiming to have 15 million electric vehicles and 1 million public charging points on the road by 2030, but is set to miss the EV target. The number of EVs registered in the country stood at 1.4 million in early 2024.

- Tarnished by the dieselgate scandal, iconic carmakers VW, BMW and Daimler struggle in the global race to green auto transport with heavy competition, for example from the U.S. and China.

- Rail development is slow, with few signs of improvement. Rail operator Deutsche Bahn has become the target of strong criticism as long-delayed investments in infrastructure are causing severe disruptions in long-distance travel. Germany introduced a flat-rate ticket for regional and local travel, which has had a positive impact on passenger numbers. Mobility experts say there are too few attractive public transport services in rural areas for a serious shift away from the car.

- Freight produces one-third of transport emissions in the trade hub in Europe’s heart. Volumes are growing, but greening the sector remains a sideshow.

- Low water levels in the Rhine river — Germany’s most important shipping route for raw materials — as a result of climate change threaten to severely disrupt supply chains reliant on water transport.

Agriculture

- The sector is responsible for 8 percent of total GHG emissions (mainly methane from livestock farming, nitrous oxide as result of nitrogen fertilisation; excluding LULUCF).

- Emissions have fallen by a quarter since 1990, in large parts in years after the German reunification, when livestock numbers were reduced. They accounted for about 9 percent of total emissions in 2023.

- Like everywhere in the world, the reduction of emissions in farming also depends on shifts in food consumption, often part of polarising debates when they require changes to personal lifestyles and traditional eating habits.

- Annual meat consumption in Germany is in decline, and many people consider the impact their dietary choices have on the environment and climate.

- Policymakers are in close talks with farmers to balance their needs with the need to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change. However, protests against decarbonisation measures by the farming industry dominated headlines in early 2024 - even though climate policy was widely regarded as a trigger rather than an underlying cause for the farmers' dissatisfaction.

Land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF)

- Taken together, forests, peatland, meadows and other land in Germany are net carbon sinks in some years, and a net greenhouse gas emission source in other years (-2 million tonnes CO2 equivalent in 2022).

- Climate law target: -25 mln tonnes by 2030, -35 mln t by 2040, -40 mln t by 2045.

- A 2024 report from the agriculture ministry said forests across Germany have become a net source of carbon dioxide for the first time since records began. The environment agency (UBA) says the emissions trend is “increasingly dramatic,” as recent years have shown decreasing net carbon storage in forests and high emissions from organic soils of farmland and grassland.

- The government introduced measures for natural climate action, and a moorland strategy.

Find an interviewee

Find an interviewee from Germany in the CLEW expert database. The list includes researchers, politicians, government agencies, NGOs and businesses with expertise in various areas of the transition to climate neutrality from across Europe.

Get in touch

As a Berlin-based energy and climate news service, we at CLEW have an almost ten-year track record of supporting high-quality journalism on Germany’s energy transition and Europe’s move to climate neutrality. For support on your next story, get in touch with our team of journalists.

Tips and tricks

- CLEW’s Easy Guide to Germany’s transition with background information and links to key energy and climate data.