IPCEI: Germany and France bet on joint EU platform for sustainable industry

*** Please note: this factsheet is part of a CLEW cross-border cooperation, exploring the Franco-German approaches to climate and energy and how these affect the vision of the EU’s energy future. You can find the full dossier here.***

Achieving a sustainable transformation of the European economy is a vast and urgent project that can exceed the capacity of individual companies and entire countries. The Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) scheme is an European Union (EU) subsidy programme that aims to bridge the aims-capacity gap by fostering cross-border innovation and marketability of strategically relevant technologies in resource-intensive areas. The IPCEI framework in its current form was launched in 2014 under the aegis of the EU Commission’s internal market and industry department. It does not involve support disbursements by the EU but rather sets clear rules for providing state aid when several member states work together.

The Strategic Forum for IPCEI, an expert group bringing together representatives of member states, industry and the research community, created in 2018, is meant to provide a “common vision” for creating key industrial value chains in the EU. In its first report, the forum identified six priority areas for where member states should come together towards:

- Connected, clean and autonomous vehicles

- Hydrogen technologies and systems

- Smart health (digitally aided)

- Industrial ‘Internet of Things’

- Low-CO2 emissions industry

- Cybersecurity

Climate action and its impacts on economic and social stability is thus among the core priorities the EU intends to address with improved coordination under the IPCEI scheme. The forum concluded that the scheme can help to “fill funding gaps” and overcome “market failures” in the budding low-carbon industry. To this end, it aims to combine public and private funding and other resources from countries across the bloc. The scheme will therefore provide support, through target subsidies, to technologies that several member states deem require a certain level of progress and maturation. A definition provided by the German economy ministry says that, to be accepted, any IPCEI must meet the following criteria:

- Makes a contribution to the EU’s strategic goals

- Is conducted by at least four member states in collaboration

- Includes co-financing by involved companies

- Is expected to generate positive spill-over effects across the EU

- Sets out ambitious goals regarding research and development

All of these must notably aim to contribute to “economic growth, jobs, the green and digital transition and competitiveness for the Union’s industry and economy.” In a response to a parliamentary inquiry, the German government stressed that all state-funded projects come with conditions regarding job creation and preservation, sustainability and environmental protection, protection of intellectual property and other aspects. IPCEIs also feature a so-called ‘clawback’ mechanism, which stipulates that grantees are obliged to pay back support funds if projects become profitable faster than expected, which could amount to the entire grant being repaid.

Russia’s war and green subsidy race reassert IPCEIs’ importance

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing European energy crisis of 2022 greatly underscored the strategic aims outlined in the scheme. IPCEIs took centre stage in the RePowerEU programme, intended to wean the bloc off of Russian fossil fuels, counter rising energy prices and supply chain disruptions.

State funding for IPCEIs is partly raised through EU’s Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF). This extended emergency measures taken after Russia’s invasion until 2025, to accelerate the rollout of renewable energy and energy storage, and promote decarbonisation of industrial production processes. The scheme is also instrumental in the EU’s Green Industrial Plan, the bloc’s response to efforts in other parts of the world to fast-track the development of more sustainable industries with state aid, such as China’s turbocharged renewables expansion or the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

While Franco-German initiatives are widely considered essential for developing a viable EU-wide strategy, they attracted criticism for lacking a joint vision in the key fields of energy policy and industrial transformation. This has led to difficulties in agreeing on funding mechanisms for transition technologies and national support programmes, such as Germany’s national 200 billion-euro support package in the energy crisis, running in parallel to joint EU efforts and cementing differences in national spending power.

U.S. think tank Atlantic Council commented in early 2023 that IPCEIs can provide a possible remedy “by relaxing state aid rules, adding tax credits, and simplifying procedures for investments especially on breakthrough innovation and infrastructure.”

France and Germany dominate EU subsidy regime

As the EU’s two most populous states and biggest contributors to the bloc’s economic output, core members Germany and France historically have played a leading role in setting European standards for state aid and industrial development. Due to their large weight in the EU economy, they also are the greatest benefactors of subsidy schemes. Thanks to larger administrative resources, their access to aid programmes even outnumbers their contribution to the European budget: since the outbreak of the Ukraine war, France and Germany accounted for more than 75 percent of the EU-approved state aid programmes, while contributing just about 40 percent to the 2021 budget and under 40 percent to its industrial output.

In 2022, EU think tank Bruegel criticised the IPCEIs’ design, arguing that it “is not up to the task of disciplining state aid.” Instead, it argued the subsidy vehicle could lead to “uncoordinated national approaches” and could “create risks for fair competition in the EU” by fostering a race for support money by individual state governments. The delineation of IPCEI criteria is too loose and its procedures too opaque, the think tank argued. This could risk further boosting already strong industrial states with more resources, as they could model the scheme on particular national needs, rather than promoting EU-wide development. “The loose definitions, which can be redefined by the European Commission, could lead to a further watering down of state-aid disciplines in the name of strategic autonomy,” it concluded.

However, the two countries’ economic entanglement and cooperation runs deep, beyond the reach of state subsidies and EU projects. In 2022, Germany remained France's leading trading partner by a long way (although its share was shrinking), its fifth-largest investor and the largest in terms of individual projects. France, on the other hand, was Germany's fourth-largest trading partner and the sixth-largest investor in German stocks.

The large volume of investments between the neighbours span across the economy, with significant shares of vehicles (cars, aviation), other machinery, chemicals, consumer goods, food production and information technology. According to government-sponsored German investment agency GTAI (Germany Trade and Invest), 5,700 French companies were established in Germany in 2021, and French firms were among the top five foreign employers in Germany, creating over 400,000 jobs. Conversely, about 2,500 German companies created some 320,000 jobs in France as of 2020, GTAI said.

IPCEIs as planned launchpad for European Green Deal targets

IPCEIs are particularly relevant for technologies in industries that are key to achieving the sustainability targets outlined in the European Green Deal. France and Germany have been among the most active states in deploying the scheme as a vehicle for Europe’s transformation. At the end of 2022, French economy minister Bruno Le Maire, and his German counterpart Robert Habeck released a joint statement calling for “a renewed impetus in European industrial policy”. Pointing to the “challenging context”, they insisted on building the EU’s strategic sovereignty in energy and industrial policy and announced the launch of new Franco-German cooperation projects in the hydrogen and battery sectors. These are needed to boost the development of energy storage at the European level, as the continent expands its reliance on renewable energy.

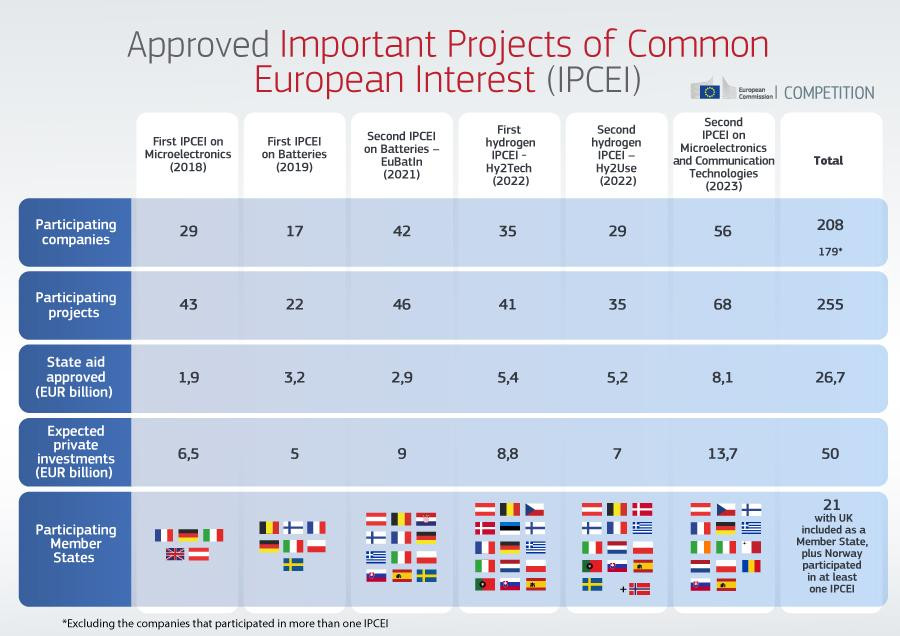

As of early 2023, several research and development projects as well as first industrial deployment projects for the joint production of batteries and hydrogen have received approval by the EU Commission. The 27-billion-euros of state funding for six approved IPCEIs are hoped to unlock a wave of additional private investments that would raise the tally up to some 80 billion euros.

Battery value chains for Europe

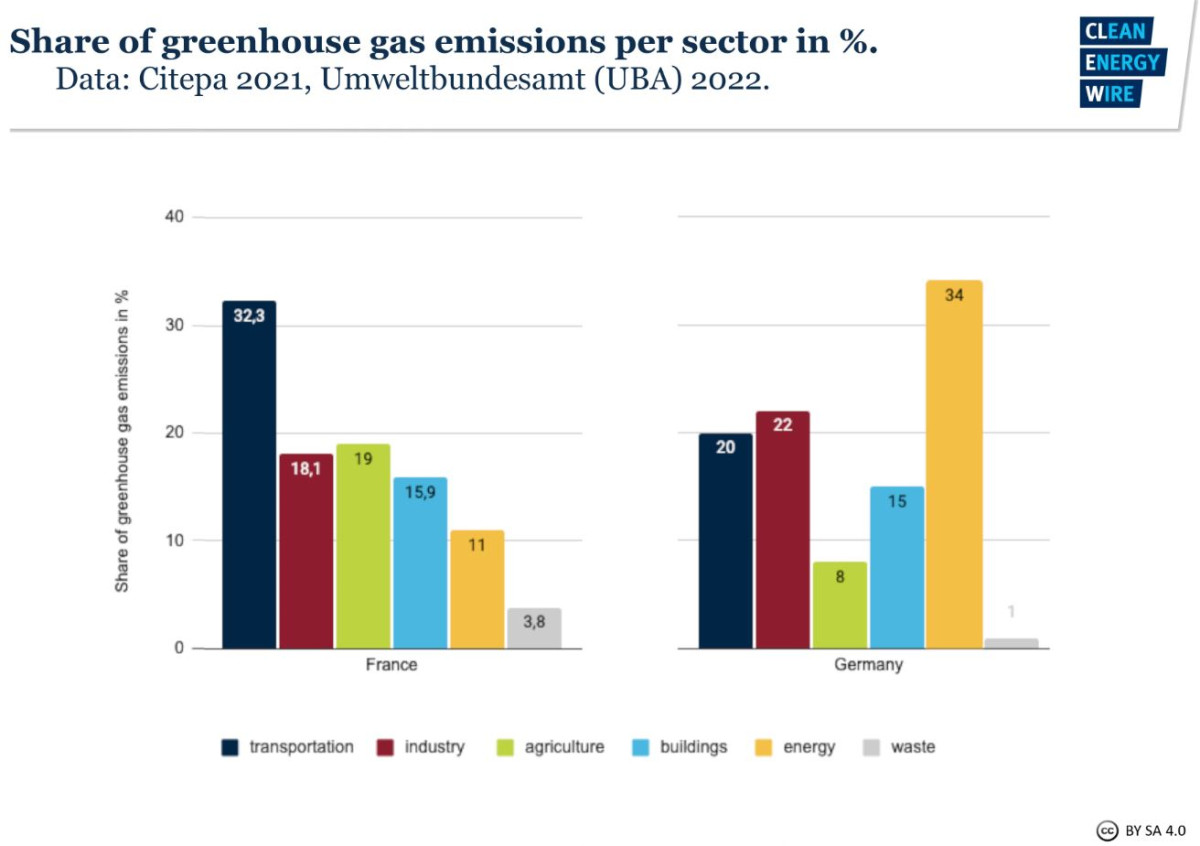

“Clean mobility” is key to the energy transition and climate targets in the EU. Transport still makes up a quarter of the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the sector remains one of the few where emissions still lingered above 1990 levels as of 2019 in the EU. In Germany, transport accounted for 20 percent of total emissions in 2022, and in France this was higher at around 30 percent. By 2050, the EU intends to reduce transport-related greenhouse gas emissions by 60 percent compared to 1990 levels, especially through the phase-out of fossil fuel powered vehicles. Batteries for electric cars are a key component needed to ensure this shift and a core part of value creation in the automotive industry of the future.

France and Germany will to join forces in the field of electric batteries for vehicles and beyond, according to announcements dating as far back as 2014. “The emergence of a French and European industrial offering in the battery sector is one of the government's priorities,” the French economy ministry reaffirmed in 2022. In 2021, Germany’s economy ministry asserted that cooperation between the two countries “has the potential to create a new battery champion in Europe.”

At the EU level

The bi-lateral Franco-German ambition is part of a broader scheme of EU initiatives. The European Battery Alliance (EBA) was launched in 2017 and notably aims to build a sustainable value chain in Europe to cover the entire battery production process. The alliance is part of a larger attempt at breaking the region’s dependence on non-EU, particularly Asian, supplier countries.

The European Strategic Action Plan on batteries, published in 2018, aims to prepare the European car industry for the 2030 shift to low and zero-emission vehicles. The action plan has six priority areas, which include securing access to raw materials, supporting domestic and sustainable battery cell manufacturing, research and innovation, and training a highly-skilled workforce.

“There is much to be done in the coming years to achieve the necessary level of technological expertise in the EU, to secure the supply of raw materials from third countries and EU sources and to ensure that batteries can be recycled safely and cleanly. Investing in staff is the joint responsibility of the government and the business community”, noted the European Economic and Social Committee in a first progress report on the implementation of this Plan in 2019.

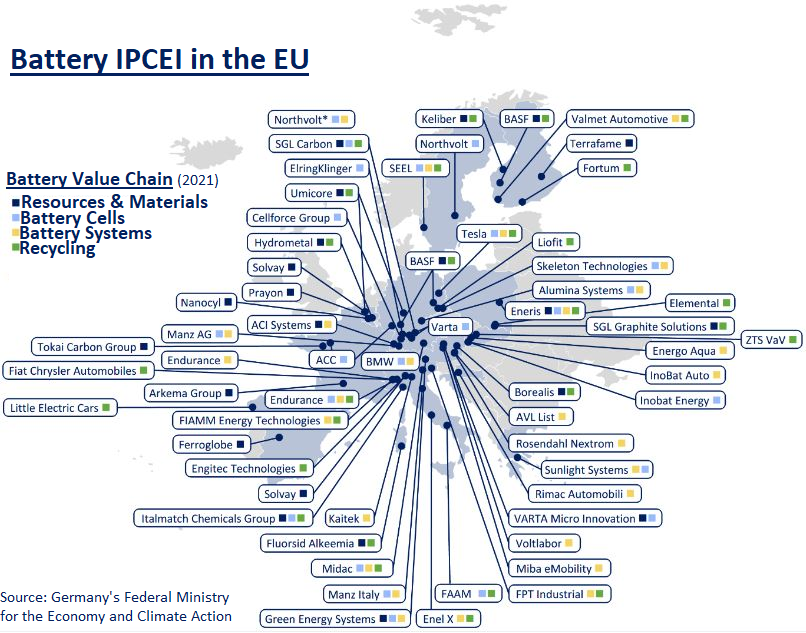

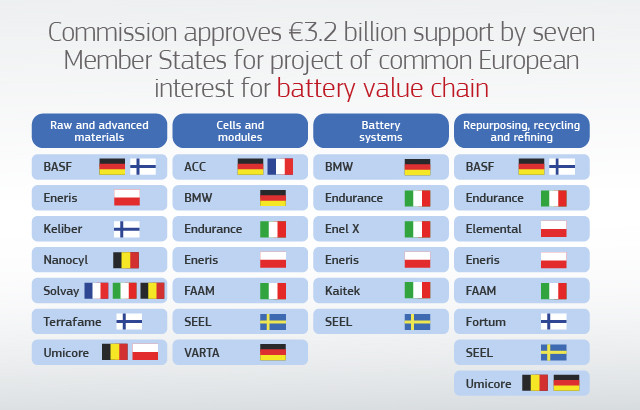

The first IPCEI battery project was launched in 2019, with completion planned for 2031. It involves 17 companies from seven countries (France, Germany, Belgium, Finland, Italy, Poland and Sweden) and mostly industrial actors, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The project also involves over 70 external partners, including public research organisations from across Europe. Member states were to provide up to 3.2 billion euros in funding in the following years to unlock an additional 5 billion euros in private investments.

The ‘pioneer’ battery IPCEI has focused on research and development along the entire value chain: “from mining and processing the raw materials, production of advanced chemical materials, the design of battery cells and modules and their integration into smart systems, to the recycling and repurposing of used batteries,” the EU Commission said. Innovation efforts will also specifically be aimed at improving environmental sustainability to reduce the carbon footprint from waste generation during the production as well as during the dismantling, recycling and refining stages, the Commission specified.

A second and complementary battery IPCEI covering the entire battery value chain, named “European Battery Innovation”, was approved in 2021 and is scheduled for completion by 2028. It also aims to support research and innovation, involving 42 entities from twelve countries, including France and Germany (as well as Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Greece, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden). Member states are due to provide up to 2.9 billion euros in funding over the next few years, which are expected to leverage a further 9 billion euros in private investments.

As of May 2023, the two IPCEIs in battery production alone are supposed to create some 6,000 jobs in Germany, according to a government response to a parliamentary inquiry. The IPCEIs are divided into 14 individual projects carried out together with France, Italy, Belgium, Poland, Austria, Spain, Sweden and others and have a combined maximum state support of nearly 1.5 billion solely from Germany.

In France, IPCEIs focussing on batteries are part of an wider 8-billion-euro national plan of investment into pan-European projects. These projects also include semiconductors, hydrogen and the healthcare sector, as announced in 2021 by French economy and finance minister Bruno Le Maire. “They will enable us – the French and Europeans – to compete technologically with the best standards in the world, those of China and the USA,” he said.

France announced it would earmark 1.5 billion euros for its Douvrin electric battery plant project of the Automotive Cells Company (ACC) to prepare for the European Union's possible 2035 de facto ban on internal combustion engines, which has not yet been adopted, not least due to German opposition.

The first French ‘gigafactory’ for e-car batteries was inaugurated in northern France in May 2023. By 2030, it aims to produce 500,000 batteries for electric cars per year, creating some 2,000 jobs. By May 2023, the French government had already invested some 845 million euros in this 7 billion-euro project which, with additional funding from Germany, brought the bilateral state support to a total of 1.3 billion euros. French economy minister Le Maire said the factory’s opening marked “the first time that France and Europe create a new industry since the time of Airbus,” the European aircraft manufacturer that is regarded as Europe’s prime example of successful industry cooperation.

Launching a European hydrogen network

The creation of a European (and global) industry network for the production and retail of hydrogen is considered another key area for maintaining technological leadership in the energy transition. In early 2023, France and Germany announced a joint ‘roadmap’ to accelerate their cooperation in this strategic sector for industry decarbonisation. “We are both leaders in this area which is instrumental to decarbonise our industries”, Bruno Le Maire and Robert Habeck said in their joint statement on European industrial policy in November 2022.

Both countries already produce the synthetic gas obtained via electrolysis using electricity and splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen. In both France and Germany, this is to a large extent done with the fossil fuel natural gas as the power source, resulting in so-called ‘grey hydrogen’. As of 2022, France produced some 900,000 tonnes annually, which accounted for about 3 percent of the country’s emissions.

The EU initially planned on developing ‘green hydrogen' only, which is produced using renewable energy to split water molecules. Germany produced some 5 percent of its hydrogen with renewables in 2020. However, by obtaining exemptions for nuclear-derived ‘pink hydrogen’ for certain industry applications in mid-2023, France successfully insisted on guarantees for using its nuclear fleet in European decarbonisation plans.

At the EU level

The European Hydrogen Strategy, adopted in 2020, focuses on five main levers: investment support, supporting production and demand, creating a hydrogen market and infrastructure, research and international cooperation. It calls for the deployment of at least 40 GW of electrolysis capacity from renewable energy by 2030 and the installation of at least 6 GW of renewable hydrogen electrolysers (to produce up to 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen), in order to decarbonise different sectors that are otherwise difficult to wean off fossil fuels. Some 10 million additional tonnes of hydrogen shall be imported to the EU by 2030.

A Clean Hydrogen Partnership was also established in November 2021. It counts 18 member states from the EU and beyond (UK, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland) to support research and innovation in the hydrogen ecosystem.

In the context of Europe’s large-scale shift away from Russian fossil fuel imports, hydrogen is considered a key substitute for natural gas. Therefore, the EU bolstered its strategy through the REPowerEU plan of May 2022, increasing the focus on renewable hydrogen with an ‘accelerator’ to facilitate the phase-out of Russian imports. Jointly developing the scale-up of hydrogen infrastructure and supporting hydrogen investments are also identified as key areas to support hydrogen uptake in the EU.

The creation of a European Hydrogen Bank (a financing instrument managed internally by the EU Commission) was announced by Ursula Von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, in 2022. A pilot auction is to be launched in autumn 2023 and an informal group of representatives from the energy ministries, the Hydrogen Energy Network, was created, scheduled to meet every year.

As part of the Fit for 55 Adjustment Package (to reduce EU emissions by 55 percent by 2030 compared to 1990 levels), the EU Commission has cut taxes on hydrogen (Energy Tax Directive), set a target of 50 percent hydrogen in industry and of 2.6 percent in transport (Renewable Energy Directive), regulation of the hydrogen market (Gas Package), and set infrastructure targets for hydrogen or electricity (ReFuelAviation Initiative, FuelUEMaritime Initiative, regulation on alternative fuel recharging infrastructures).

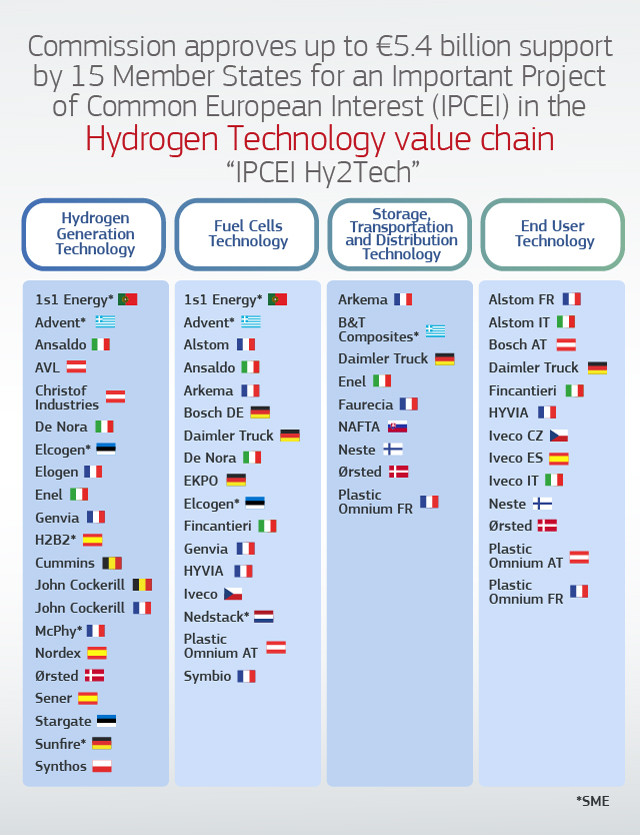

IPCEIs again have a role to play in this shift, supporting investment and innovation. A first project, the IPCEI Hy2Tech, launched in 2022, is intended to develop innovative decarbonisation technologies for the industrial and the mobility sectors. It involves 35 companies and 41 projects from 15 Member States, including France and Germany (along with Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Spain). Member states are to provide up to 5.4 billion euros in public funding, which are expected to unlock additional 8.8 billion euros in private investments.

A second supplementary project, IPCEI Hy2Use, was created in the same year and notified by thirteen states, including France but not Germany (instead alongside Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden). They are to provide up to 5.2 billion euros in public funding and expect to unlock an additional 7 billion euros in private investments. It includes 29 companies and start-ups, participating in 35 projects and focuses mainly on the construction of hydrogen-related infrastructure and the integration of hydrogen into the industrial sector. France has announced its ambition to become a leader in the production of hydrogen, partly since it already operates the largest fleet of electrolysers in the world: about six percent of global capacity.

The 2018 hydrogen deployment plan for the French energy transition, listed three markets: the desulfurization of petroleum fuels (60%), ammonia synthesis mainly for fertilizers (25%) and chemicals (10%). It was then 94 percent derived from fossil fuels in France (gas, coal, hydrocarbons).

Since then, Paris also launched a National strategy for the development of low-carbon hydrogen, in 2020. “France has an advantage here in the form of nuclear energy, which has been approved as a source of renewable energy,” government business agency Business France said. It added that further development of this sector could therefore ensure the creation of up to 150,000 jobs.

In late 2021, the French economy minister Bruno Le Maire stated that France would invest 3 billion euros in 15 joint-European hydrogen projects that will benefit French companies. These companies include chemicals group Arkema, carmaker Renault, automotive suppliers Faurecia, Plastic Omnium, hydrogen production and storage equipment manufacturer Mcphy and industrial gases group Air Liquide.

At the beginning of 2022, France announced it set aside an exceptionally high sum of 1.5 billion euros for IPCEI action on hydrogen to support research on electrolysers and their market ramp-up, produce carbon-free hydrogen, and deploy these solutions in industry, as well as involve ‘gigafactory’ projects for new-generation electrolysers, and for the industrialisation of other technological building blocks (fuel cells, tanks, materials, etc.). By November 2022, 2.1 billion euros had been invested in the first 10 IPCEI hydrogen projects, and 3 billion euros had been earmarked to support all or part of the next 22 pre-selected projects in sectors such as cement, glass and fertilizers. In addition, 4 billion euros were to be mobilised to support the production of hydrogen by electrolysis, so that economically sustainable low-carbon hydrogen can be produced in France.

Germany also plans to greatly boost its hydrogen production and transport capacity, releasing its own National Hydrogen Strategy in 2020 and updating it in 2023. By 2021, the Economy and Climate Action Ministry (BMWK) stated that the federal government, together with states, had set aside 11 billion euros for 62 pre-selected IPCEI projects on green hydrogen. In spring 2023, the government listed seven ongoing IPCEIs (Hy2Tech / Hy2Use / Hy2Infra / Hy2Move / KUEBLL / AGVO) divided into 47 individual projects, all for hydrogen production and distribution with German participation. The eligible support costs of the projects, that involve 45 companies, amount to some 17.5 billion euros, which the government hopes will help create more than 14,000 jobs in the budding industry.