Opportunities and opposition – East Germany's oscillating energy transition

Contents

2) Are there still ‘East Germans’?

3) East Germany only makes up a small fraction of the country

4) Major factors setting the “two Germanys” apart today

5) East-West divide permeates energy and climate policy

6) A lingering political divide

7) An energy system shaped by the Cold War

8) What role have climate and the environment played since 1990?

9) Are Eastern German states energy transition frontrunners?

The making of East Germany

After Germany’s defeat in World War II, the country was split by the victorious Allies into a Western zone – occupied by the U.S., the UK, and France – and an Eastern zone, occupied by the Soviet Union. The western zone turned into the Federal Republic of Germany (GFR), which was integrated into the Western capitalist system, whereas the eastern zone turned into the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which became part of the communist bloc. While geographically in the East, Bavaria was also made part of the GFR.

After peaceful civil society revolutions across the communist bloc in 1989, Germany was reunified in 1990 under the GFR’s system, and the united country’s capital was moved from Bonn to Berlin in 1999. Today, 'eastern Germany' commonly refers to the five larger states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. They are also sometimes referred to as the “Neue Bundesländer” (new states), in contrast to the “Alte Bundesländer” (old states) in the West.

Special case: Berlin

Berlin is in the eastern half of modern Germany. It became the capital of Imperial Germany in 1871, but in 1945 the city was split among the Allies and ended up with West Berlin as an enclave in the GDR and East Berlin as the GDR’s capital. Owing to its legacy as a divided city in the Cold War, Berlin today has several unique demographic traits that make the unified country’s capital difficult to integrate into metric comparisons.

High net-migration since the early 2000s, and the large city’s divided history with strong links to the West let Berlin as a whole deviate markedly from the rest of the former GDR. Home to roughly 3.7 million people in 2022, the capital is therefore often excluded or treated separately in statistical analyses for eastern Germany.

Are there still ‘East Germans’?

A 2023 analysis by the German Institute for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM) found that the number of people in the country with an East German identity was between 16 and 26 percent. The analysis examined the entire German population of 83 million people and responses depended on the definition of the term, which could, for example, include one’s place of residence, place of birth or upbringing, or one’s family history. Sociologist Sabrina Zajak, who led research on the report, said “it’s not easy to answer” who exactly counts as East German – even though this question has great implications for quantifying and evaluating debates around fairness in the country, for example when it comes to filling more executive positions with East Germans.

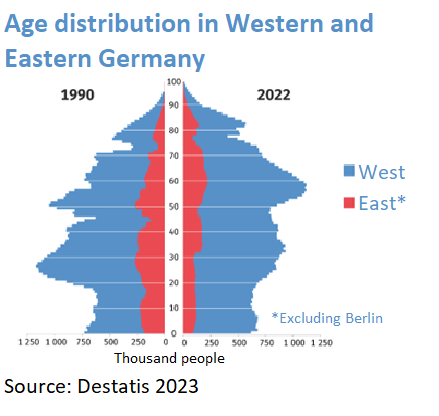

East Germany only makes up a small fraction of the country

While the territory of the former GDR makes up about a third of today’s Federal Republic in total area, the share of the country’s population living there is a lot smaller. Before reunification in 1990, West Germany’s population, excluding West Berlin, was four times larger than East Germany’s. In the time since the Berlin Wall fell, the population in the West has grown ten percent to 68 million in 2022, while in the East it dropped 15 percent to about 12.6 million as a result of internal migration and a lower birth rate, shows data compiled by Germany’s statistical office Destatis.

Western states today outnumber eastern states five-to-one in terms of inhabitants. In 2021, the Federal Institute for Population Research (BiB) found that the number of people living within the territory of East Germany had fallen to the same level as in 1910. The most populous western state, North Rhine-Westphalia, had in 2022 a significantly larger population (18 million) and therefore more voters than all eastern German states combined. However, voters from eastern states have better political representation in Germany’s federal system through the Council of States (Bundesrat), where the eastern states have 19 seats, while North Rhine-Westphalia has six.

Major factors setting the “two Germanys” apart today

Despite being reunited for more than three decades, several socio-economic factors continue to uphold a sense of separation between the two former halves of Germany, even if many people do not consider themselves East German or West German, and laws, conventions, infrastructure and other aspects of everyday life for the average citizen exist for Germany as a whole.

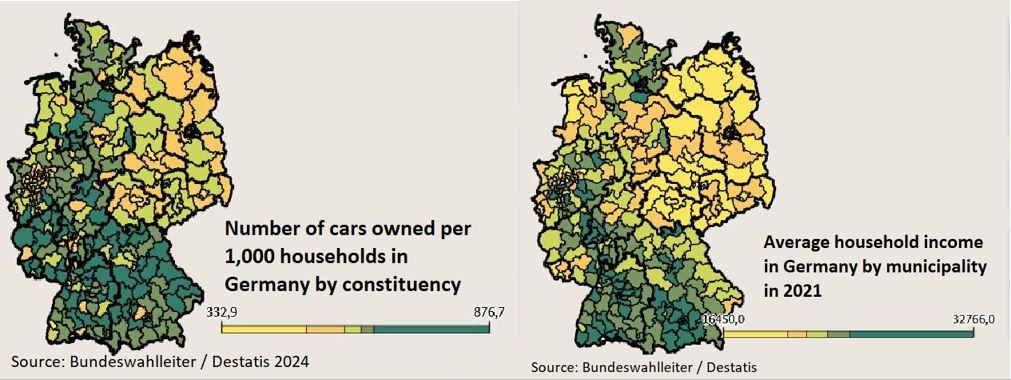

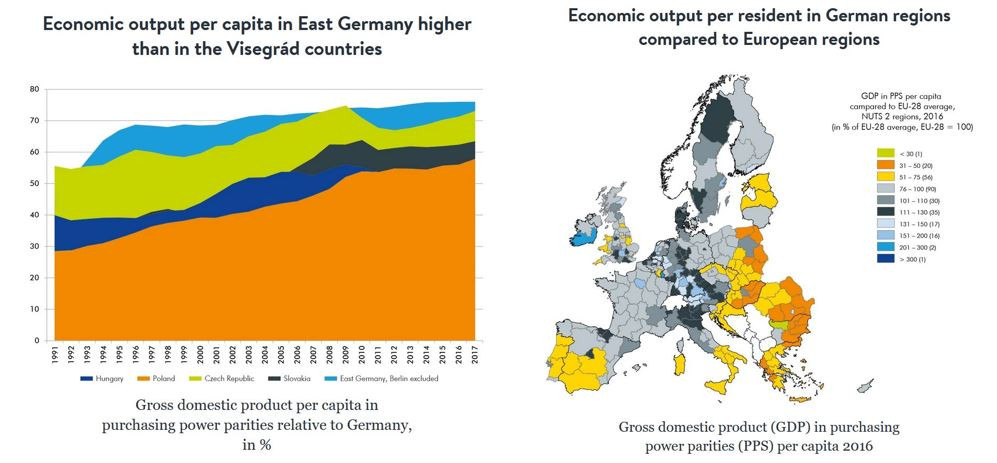

Germany invested an estimated two trillion euros in its eastern states, leading to a significant yet incomplete levelling-up of living conditions. However, nearly 35 years after the country’s reunification, the former border is still visible in statistics. With the exception of Berlin, almost all companies listed on Germany’s stock market are located in western states. In 2023, full-time employees in old East Germany earned 817 euros less per month than their compatriots in the West: the average wage in the West was 4,586 euros, compared to 3,769 euros in the East. However, they still surpassed their fellow formerly communist Polish neighbours by more than 2,100 euros per month.

Eastern Germany on average has a more rural and less formally educated population than western Germany. At the same time, the region is older and has a higher youth unemployment than western states. The migration of many highly skilled and motivated people to western Germany after the collapse of the Soviet Union further affected the sociological composition of the East, exacerbating structural problems such as a lack of doctors or crumbling infrastructure. However, many of these problems also exist in less affluent and rural parts of western Germany. Aside from Berlin, immigration between 1990 and 2022 was seven times higher to western states than eastern states. The share of non-nationals residing in West Germany (16%) is therefore much higher than in East Germany (7%).

The 'brain drain' of skilled workers migrating to the West in the 1990s and the lack of skilled immigration in the past decades have contributed to the fact that the East has trailed the West in terms of productivity, research institute IW Halle found in an analysis on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of reunification in 2019. "In addition, there is the permanent subsidisation of unproductive structures and a lack of entrepreneurship, which can be explained by the lack of capital reserves and the experience of the disruptive change of the political and economic system," the researchers found.

Further factors found to be keeping down developments in the East were mistakes made under the "Treuhand" privatisation scheme and the levelling of the East competitiveness due to the revaluation of its currency by adopting the Deutsche Mark. All of this meant that an initial momentum of convergence came to an end around the year 2000, the IW Halle said. However, it added that "in the 1990s, far more industrial jobs were lost in western Germany than in the eastern part of the country."

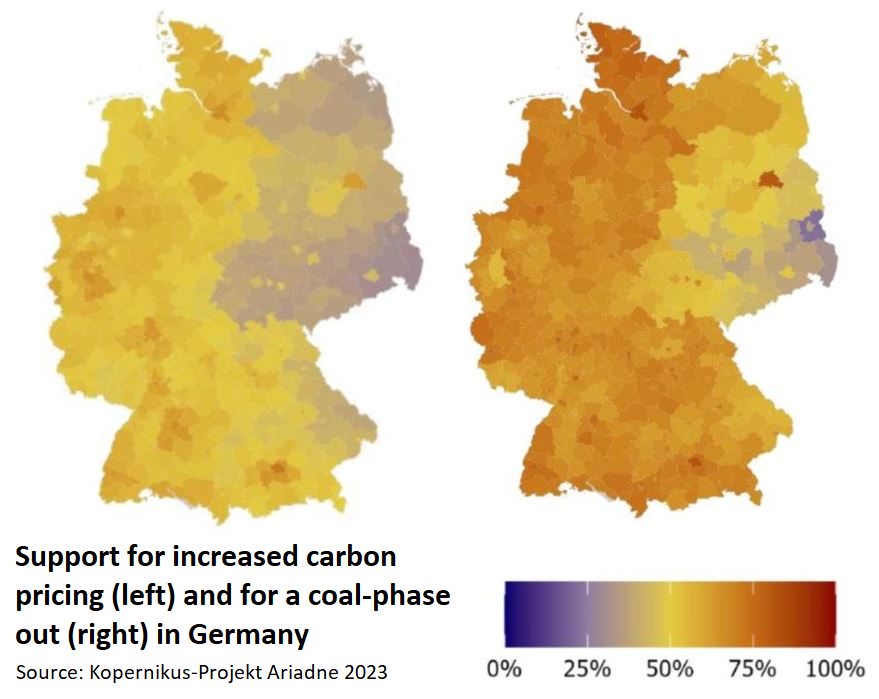

East-West divide permeates energy and climate policy

A study on regional attitudes towards climate policies in Germany found that, in general, measures enjoy more support in densely populated regions and cities. The study examined the years between 2017 and 2021 and was carried out by the Ariadne research project. It showed that East Germans tend to be on average more sceptical when it comes to concrete steps for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon pricing, the phase-out of combustion engines or a levy on the climate impact of buildings. A perceived injustice regarding the distribution of costs and benefits and a generally higher distrust in public institutions were found to be factors further reducing the readiness to act, both of which are more widespread in the East.

The support for measures sometimes showed staggering geographical differences across Germany, with attitudes towards the country’s planned coal phase-out varying by as much as 60 percentage points. Eastern coal mining regions showed the lowest acceptance and, contrary to the rest of the country, support for the move away from coal even was found to be in decline in some eastern regions. Researchers from Ariadne said it was difficult to say why this difference exists, but added that their initial findings suggest a more difficult overall economic environment and lower wage levels, as well as the rapid pace of earlier cuts to the region’s coal industry pose additional hurdles there. Oppressed public debate about and reporting of environmental challenges in the GDR might further explain a more widespread readiness to ignore climate-related dangers, they added.

Especially energy costs continue to occupy voters’ minds in the East. After a recent analysis by price comparison website Verivox found that households in eastern states pay much higher electricity prices when adjusting for purchasing power, a survey by energy company Octopus backed the conclusion that this is fuelling a feeling of disadvantage and unfair cost distribution there. Four out five people in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg said the power prices they must pay are too high

However, the study also showed that attitudes can change if political intervention is used to make measures more palatable, for example by letting the locals participate financially in renewable power production in their region. In the northeastern states of Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, where changes to the support scheme ensured that wind park operators must share their revenues with the municipalities that host the turbines, support for onshore wind power installations is growing.

The study found that 54 percent of people in the West say they are ready to pay higher prices to stop global warming, whereas the figure was only 39 percent in the East, with support being lower in both urban and rural areas than in comparable regions in the West.

The repercussions of Russia’s war on Ukraine and the ensuing economic and energy trading sanctions often hit regions in Eastern Germany more directly than in the West, for example at the Schwedt oil refinery in Brandenburg. The facility near Berlin had processed Russian oil imports since GDR times until sanctions put an end to this in early 2023. After rerouting supply chains, the refinery now works with oil from other countries but still has a lower output than before Russian supplies stopped.

However, a survey by climate interest group Initiative Klimaneutrales Deutschland in mid-2024 found that more than two thirds of respondents in eastern state Saxony are generally in favour of the switch to renewables. Only 18 percent did not agree.

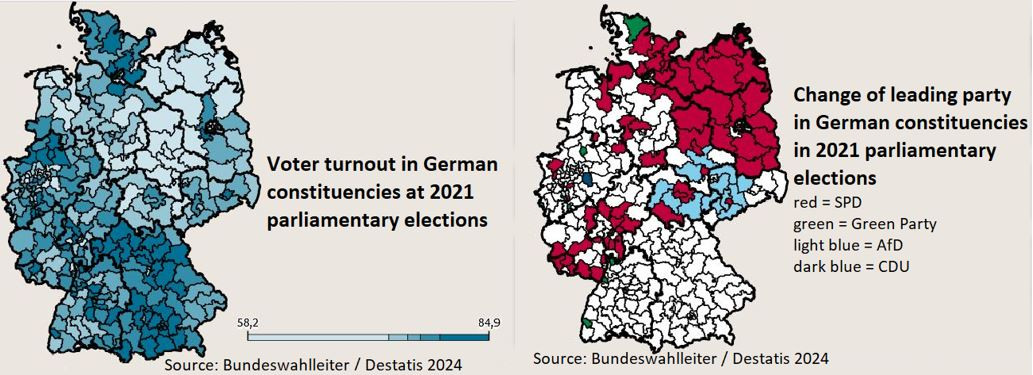

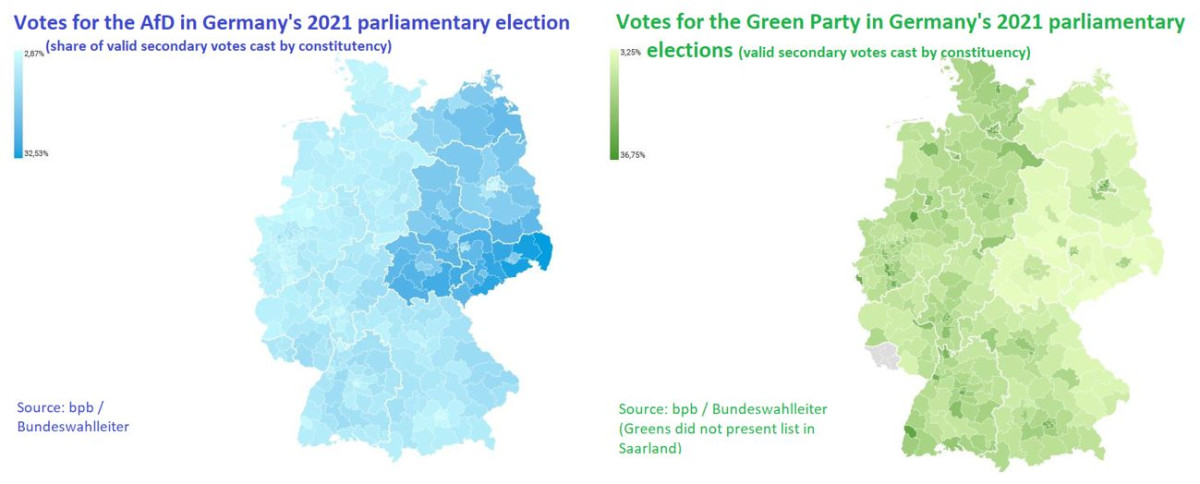

A lingering political divide

Differences also persist with respect to political preferences in both parts of Germany: The ro-business Free Democrats (FDP) and the Green Party have failed to gain a solid foothold in large parts of eastern Germany, and also the Social Democrats (SPD) have struggled in Thuringia and Saxony. While the SPD faced a direct leftwing competior in the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), the successor of the GDR’s Socialist Unity Party (SED) that later turned into the Left Party, the Greens and the FDP have traditionally found it difficult to find support in rural and working-class environments.

The three parties that formed the coalition government in 2021 under SPD-chancellor Olaf Scholz suffered losses in the East at the 2024 EU elections – the first nationwide vote after the coalition entered government. Instead, the region voted in significant numbers for the far-right populist Alternative for Germany (AfD), the new nationalist-left populist Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), and the conservative centre-right opposition party Christian Democrats (CDU).

While support for the Green Party tends to fall in rural communities in the West, too, in the East this was compounded by a parallel increase in popularity of the AfD in the countryside, found voting data analysis of the 2021 national elections by the Thünen-Institute. With an average share of nearly 20 percent of votes, the AfD was twice as popular in eastern regions than in western ones. Supporters of both populist parties that have become major political actors in the East also shared the lowest willingness by far to support climate action policies, showed a study by the University of Erfurt which examined attitudes of all voters in Germany.

“Populists promise people a return to a seemingly simpler past that never actually existed,” said the federal government's state minister for Eastern Germany, Carsten Schneider (SPD), to Clean Energy Wire. He warned that the populists' positions pose a great threat to prosperity of energy transition “pioneer” Eastern Germany - a conclusion shared by chancellor Scholz, who at the ceremony for the start of construction of a semiconductor chip production plant in eastern Germany said that nationalism and resentment endanger investments in key future technologies. A survey by economic research institute IW found that many companies in the East share this view: Sixty percent of responding companies said they are worried what a success of the party will mean for EU cohesion and the common currency, the euro. Only 13 percent of companies in the East said they expect the AfD to bring economic benefits for them and 29 percent said they agree with at least some of the far-right party’s positions – compared to 22 percent in the West. Given the relatively stronger showing of the AfD in polls, the poor results for the populists in the content-based survey had been “a surprise,” the IW said.

Where does this imbalance between support for the extremist party in polls and more moderate views on concrete policies come from? According to psychologist and sociologist Elmar Brähler, the number of people with far-right views has not changed substantially since he first carried out an analysis of political attitudes in the region in 2002. However, “for a long time, these people have voted for parties other than the AfD” and still gave their vote to the SPD, the CDU or the Left Party, he said in an interview with the magazine Vorwärts. But political affiliation to certain parties is not as strongly rooted in eastern Germany as it is in the western states, which for example means people are less inclined to stick to the party that their parents voted for, Brähler said.

According to a 2017 report presented by the former government envoy for Eastern Germany, Iris Gleicke (SPD), this trait was developed as a result of the oppression of civil society in the GDR. Nearly 35 years later, this continues to weaken the strength of other parties to organise themselves at the local level.

The idea of a successful uprising by ordinary citizens against the ruling elite reverberates in the AfD’s campaigning in the region, calling back to the way East Germans brought down the GDR regime through protests. The AfD routinely seeks to paint a picture of a sinister Western capitalist and internationally connected elite in the capital of Berlin, and other urban centres, that forces its policy concepts on ‘normal’ people, noted the head of Germany's Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb) in 2017.

Poverty is often not the factor determining whether people vote for the far-right, Brähler said. Research has shown that most AfD voters are materially well-off, which would put approaches such as increased social security transfers to quell right-wing tendencies into question. “There’s no direct connection,” he said, adding that a feeling of relative disadvantage compared to western regions played a much greater role than absolute incomes. “That’s a point that cannot be overestimated when it comes to analysing dissatisfaction in East Germany.”

Research on citizen attitudes across Germany backs his point: people in eastern states generally said they are content with their lives in a large government-commissioned survey on equal living conditions published in 2024, but at the same time many answered they have it relatively worse than other parts of the country. An analysis by research institute ifo Dresden found that voters of the AfD and the BSW often are motivated by a feeling of disadvantage and fears of rapid economic and social changes. “However, the support cannot be traced back to an objectively worse economic situation,” the researchers said after reviewing voter motivations at the European elections. “Populist parties find support in regions with a high share of older voters and where people have little confidence in the future,” said the ifo Dresden’s deputy head, Joachim Ragnitz. A subjective feeling of discontent had a much greater impact than measurable economic factors, he added.

An energy system shaped by the Cold War

In line with the managed economy in the East, energy supply was centrally organised by ‘state combines’, a conglomerate of cooperating industrial entities led by the state, while the West relied on several locally organised supplier companies like RWE, which remains the country’s largest supplier to this day.

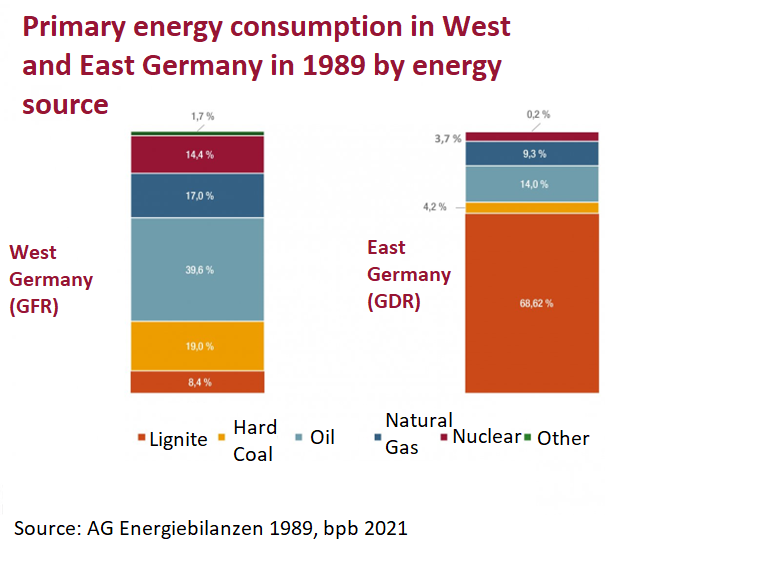

West Germany increased the use of its domestic hard coal and lignite reserves after the Second World War and soon also gained access to shipped oil imports like the rest of western Europe, but the GDR lacked secure access to imported energy during the Cold War between the capitalist and communist blocs. Despite projects such as the Druzhba (Friendship) Pipeline in the 1960s, imports from energy-rich ally the Soviet Union were unreliable and never covered much more than a fifth of the country’s primary energy demand.

The communist state therefore relied even more heavily on its domestic lignite reserves. The GDR, and later unified Germany, became the largest lignite producer in the world, and lignite is still being mined in the Lusatia region today. Through their oil imports, the western GFR attained a much more diversified energy supply than the GDR which had to rely on dirty and inefficient lignite.

Both German countries started using nuclear power in the early 1960s, but the expensive technology was developed much more extensively in the West. Contrary to West Germany, however, the GDR never saw a civil society movement protesting nuclear energy, unlike the West where fears around the perils of nuclear technologies helped birth the Green Party. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster stopped the further development of nuclear power stations in both countries.

What role have climate and the environment played since 1990?

Reunification in 1990 had an enormous impact on the East’s energy system, while the West’s infrastructure was initially only moderately affected. The introduction of market principles and the privatisation of state combines overturned an existing system that relied heavily on subsidised prices and low environmental standards to save costs. Many coal-fired power plants in the East had to be modernised, rebuilt or shuttered to comply with new federal standards, which led to a “first coal exit” in the country in the 1990s, as the Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb) put it.

Germany’s environment minister, Steffi Lemke of the Green Party who hails from the GDR, said in a 2023 interview with newspaper Die Zeit that “the massive environmental destruction of course played a part” in why East Germans revolted against their country’s government. Thanks to large investments from Germany and the EU that helped to clean-up eastern states, environmental protection gradually declined as a major topic in public debates in the East, not least because a cleaner environment accompanied a decline in economic output and available jobs in many regions.

While this happened in western Germany, too, the situation in the East was aggravated by the fact that East Germans on average have lower savings and levels of property ownership than those in the West. As such, East Germans are more vulnerable to economic disruptions such as the 2008/2009 financial crisis, which also laid the groundwork for the AfD’s founding in Western Germany.

The erasure of inefficient GDR energy and industry facilities allowed the newly unified country to almost immediately achieve a massive 30 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in a very short time. This allowed unified Germany to enter into international climate reduction efforts with a massive drop in CO2 output following the reference year 1990.

The closure of industry and energy facilities contributed to the loss of nearly three quarters of industry jobs in the former GDR. Those jobs had formed the "engine" of the communist economy, resulting in grave social and economic ramifications in the East when they disappeared. Energy companies from West Germany bought up the entire stock of energy production capacity in the East.

On the 30th anniversary of Germany’s reunification, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) lauded the achievements made by the East in the intervening decades. "We can be proud of what the new federal states have achieved in environmental protection since 1990," said Dirk Messner, head of the UBA, at the time. Marking one of the first joint environmental projects in the unified country, the “German Green Belt” turned a stretch of the former inner-German border of 1,400 kilometres into natural reserves. Messner stressed that the eastern states had been particularly successful in addressing water and air pollution. “And yet there is much to be done,” Messner added, pointing to the energy transition, mobility transition, more sustainable cities, sustainable agriculture, and circular economy as the greatest environmental tasks for the region “after the transition to a market economy and democracy.”

According to NGO NABU, the most pressing environmental tasks in East Germany today are scarce water resources in Germany’s driest region (which also play a key role in carmaker Tesla’s continuing legal woes in Brandenburg and have led to plans to install a desalination plant at the Baltic Sea to supply Berlin with freshwater); the legacy of GDR agriculture industry, where collectivisation formed the largest contiguous farming areas in the country that accelerated soil degradation and had a lasting impact on biodiversity; and the future of the massive former coal mining areas, where rewilding will be a multi-generational task.

Stats on the the energy transition in East Germany

About one third of Germany’s renewable power output came from East Germany in recent years, even though the region is home to only about 15 percent of the population. With plenty of rural areas and idle former industrial areas, such as vast opencast coal mines, there is a lot of potential for further expanding the region’s clean energy credentials. Amongst other things, this is demonstrated by plans for the East German states to collaborate together on green hydrogen production.

Data for 2022/2023; Source: Bund-Länder-Portal für Demografie, Agentur für Erneuerbare Energien (AEE)

Berlin*:

Population: 3.7 million

Renewables share gross power production: 6.1% (2022)

Installed renewable power (RP) capacity: 290 MW (2023)

Brandenburg:

Population: 2.5 million

Renewables share gross power production: 42.7% (2022)

Installed RP capacity: 14,977 MW (2023)

Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania:

Population: 1.6 million

Renewables share gross power production: 77.8% (2021)

Installed RP capacity: 7,879 MW (2023)

Saxony:

Population: 4.0 million

Renewables share gross power production: 15.2% (2021)

Installed RP capacity: 4,830 MW (2023)

Saxony-Anhalt:

Population: 2.1 million

Renewables share gross power production: 56.6% (2021)

Installed RP capacity: 9,910 MW (2023)

Thuringia:

Population: 2.1 million

Renewables share gross power production: 61.8% (2020)

Installed RP capacity: 4,538 MW (2023)

*The city state Berlin often is excluded from statistics referring to East Germany. For details, see above.

Are Eastern German states energy transition frontrunners?

At the time of reunification, renewable power sources beyond hydropower were almost inexistent in both parts of the country, but – due to the anti-nuclear and environmental movement – they saw faster initial development in the West. Driven by international agreements to tackle greenhouse gas emissions in the 1990s, federal laws to phase-in renewables and phase-out nuclear power and the liberalisation of the European energy market in the early 2000s, the energy transition quickly developed into a nationwide project. Some eastern states, especially Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, became hotspots for the expansion of onshore wind, large-scale solar PV and bioenergy generation.

Today, the country’s renewable power capacity divide is between the North and South, rather than East and West, as wind power is more abundant in the country’s flat and coastal northern half. It’s not only geographical features delaying the expansion of wind energy in the East (for example, Saxony) and West (for example, Bavaria), but also political choices. As more and more renewable power installations were built across Germany after reunification, financial benefits for the East remained modest compared to the West. Areas available for installing wind turbines and solar panels were often not owned by local residents in the East, and, to a large extent, earnings went to investors and companies hailing from the West. Likewise, citizen energy cooperatives are more widespread in the West - although many installations there are also owned by investors who do not reside in the region.

State-backed efforts to build an industry for solar panel production in East Germany led to the emergence of technology clusters in the 2000s, which for a while covered four fifths of national supply. The eastern German states of Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt in particular emerged as centres for Germany’s budding solar industry, with environment minister Lemke calling it at the time “the great political promise for the East” with respect to energy transition benefits.

Many companies in the region banked on the success of a promising and highly subsidised industry and subsequently saw their hopes dashed as China soon dominated in the manufacturing of solar panels. China sold its cheaper panels to Germany and that allowed energy operators to receive even higher profits while choking off one of East Germany’s most promising industry endeavours. Lemke argued that this “second broken promise within one decade” explained “why a term like 'transition' is seen as a threat rather than a promise” by many voters there.

With Germany’s decision to end coal-fired power production no later than 2038, East Germany has to focus on the inevitable - and perhaps even fast-tracked - end to its domestic lignite infrastructure in a region where other high-paying and secure industry jobs are few and far between. Nearly 8,000 people in Lusatia were still directly employed in the region’s brown coal business in 2023.

While efforts like Lusatia’s ‘Net Zero Valley’ bid showcase the region’s ambition to transition away from fossil fuels to new low-carbon industries, concrete projects have yet to take off at scale. The German government’s coal phase-out includes subsidies of 40 billion euros available for affected regions across the country. The aim is to spur new investments and build out local infrastructure, with 25 billion euros having been earmarked for eastern mining regions.

A pipeline running south from the Baltic Sea – initially intended to receive natural gas from Russia through the now idle Nord Stream 2 pipeline – could soon transport hydrogen instead. Operator Deutsche Regas plans to open a major electrolyser in the region and also open a facility to turn shipped ammonia into hydrogen by 2026. In early 2024, the eastern states' government launched an initiative to coordinate their efforts and make the East “the nucleus of a sustainable German hydrogen economy.”