Future ambition of Germany's energy transition faces test in upcoming election in eastern states

In a summer marked by a series of major elections across Europe, Germany gears up for another ballot in September, when half of the country’s eastern states vote for a new government. The impact of state elections in Germany on the national political landscape at times tends to be somewhat inflated in media reports. But the upcoming elections in three of the country’s formerly communist eastern states this time in fact carry enormous potential for disruption. Outcomes in each state could impact the existing national consensus on progressive climate and energy policies and the concrete implementation of measures at the local level. “Majorities for the further shaping of the energy transition are by no means a given,” found an analysis by research institute RLI of the party manifestos in the three states, adding that “setbacks cannot be ruled out.”

After French voters handed their own far-right populist force in parliament a surprise defeat in the snatch elections following on the European elections in June, the EU’s political centre of gravity faces another test, as eastern Germany decides how much influence they are ready to grant populist candidates from left and right. The votes thate are taking place almost exactly one year before the country’s next general elections in September 2025 come at a time when the government of chancellor Olaf Scholz struggles with low popularity regarding the administration’s domestic performance and a challenging international environment, where military conflicts and economic woes make a decisive turnaround regarding his government's popularity difficult for the chancellor.

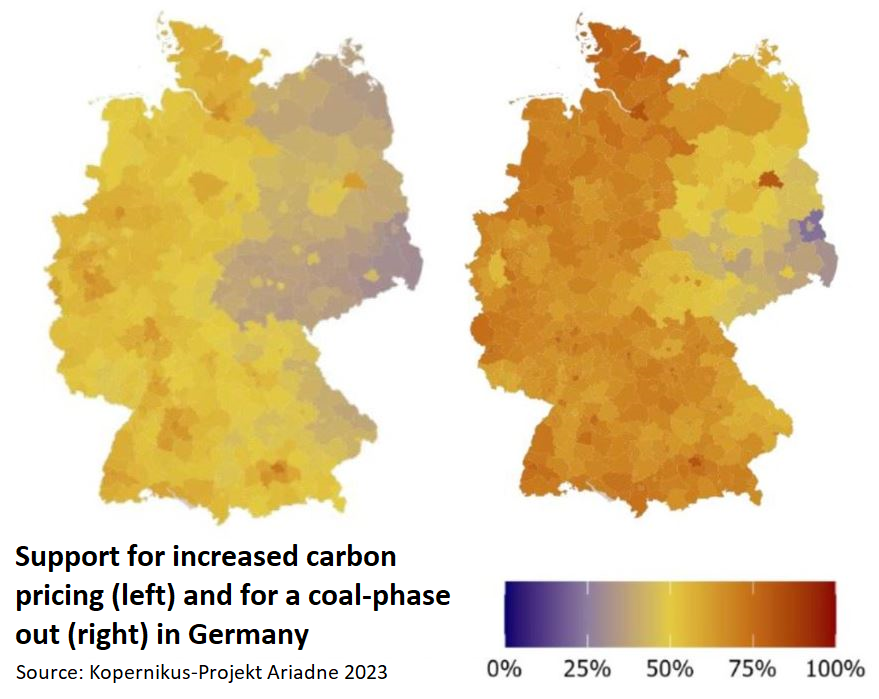

The three parties of the coalition government – Scholz’s Social Democrats (SPD), the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) and the Green Party – received together only 13 and 14 percent of the vote in state polls for Thuringia and Saxony just weeks ahead of the ballot on 1 September. At the same time, 49 percent of respondents in Thuringia and 45 percent in Saxony said they will either vote for the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) or the new nationalist-left Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance, named after former Left Party member Sahra Wagenknecht, who founded the party in early 2024. In Brandenburg, where the election takes place on 22 September, the parties of the coalition government stand stronger at 29 percent. But they still trail behind the populist parties, who together were supported by 41 percent of voters in polls.

Populists from left and right challenge energy transition, want Russian gas

While hailing from two different ends of the political spectrum, the AfD and the BSW share strikingly similar positions in a wide range of policy areas, notably regarding their rejection of immigration, opposition to the government's climate action and energy transition policy, and their often apologetic approach towards Russia’s regime under Vladimir Putin. Both parties have called for completely resuming energy trading with Russia and rejected supporting Ukraine in its defence against the Russian invasion. The AfD’s regional associations in Thuringia and Saxony have been classified as “proven right-wing extremist” by the domestic intelligence agency Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), while other regional associations and the party’s federal wing remain on a watchlist. The AfD currently polls as the strongest party in every eastern German state except Berlin.

The BSW, on the other hand, is built on networks related to the former German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) state party Socialist Unity Party (SED). The party’s leader, Wagenknecht, has repeatedly mourned the communist regime’s demise in 1989 and trivialised SED atrocities, such as the murdering of GDR citizens attempting to flee to the West. A group of leading figures from the former civil rights movement against the SED regime warned citizens a month before the state elections that Wagenknecht’s BSW relies on “lying and disinformation – well-known practices from the GDR.” The BSW has seen the fastest growth in support of any party in eastern Germany in recent months.

“Populists promise people a return to a seemingly simpler past that never actually existed,” said the state minister for Eastern Germany, Carsten Schneider (SPD), to Clean Energy Wire. “This is true for energy policy but also for moral concepts and values,” Schneider argued. He pointed at the AfD’s view of the role of women in society “akin to that in West Germany in the 1950s” or its “strategy of national isolation” in economic terms, in which domestic coal reserves are given a much higher priority than freely trading electricity across the European Union. “This approach could massively threaten Germany’s prosperity,” the government envoy said with a view to the upcoming state elections.

The AfD’s success was kept somewhat in check at the European elections in June 2024, after the party’s top candidate, Maximilian Krah, damaged his candidacy by playing down the role of the SS, the Nazi elite unit, during the Third Reich and the Second World War. Ties in his team to the governments of Russia and China also impacted his candidacy. The general rightward shift is by no means a trait that is exclusive to eastern Germany, as demonstrated by the success of right-wing populist parties in other parts of Europe like France or Italy. However, the European election highlighted a continued split between the former GDR states and their western counterparts, in which voting patterns for the eastern states deviated towards populist parties and away from the government coalition and, to a lesser degree, also the conservative opposition party Christian Democrats (CDU). Compared to the European election, the three state elections are therefore a ‘home game’ for the extreme-right AfD and the nationalist-left BSW, which already garnered some support in its first-ever election in June. Massive gains for both parties seem all but certain in September.

For government envoy Schneider, these regional variances are partly the result of persisting socio-economic differences, with voters in eastern states on average being poorer, living more rural and engaging less in civil society organisations. Nonetheless, East Germans, after a difficult period in the 1990s, have on average seen a massive increase in personal wealth, individual freedom and options to participate in politics in the 35 years since reunification. When compared to West Germans the contrast is clear as East Germans earned on average about 800 euros less per month in 2023. However, the government’s first Equal Living Conditions Report, released in July 2024, found that most people in the eastern states are generally content with their living conditions – but many also answered they believe they have it worse than people in other regions. At the same time, economic research institute ifo found that eastern states have become a driver of growth for Germany as a whole and are set to clearly outpace the national average growth rate next year thanks to a surge in purchasing power.

According to Schneider, this successful development in East Germany also owes to the region’s “pioneer” status in deploying renewable energy – eastern states supply about 30 percent of the country’s renewable power while hosting only 15 percent of the population. Chancellor Olaf Scholz has described the region’s renewable energy infrastructure as “a self-made asset” that helps the region to attract investments from companies around the world, including Tesla, Intel and CATL. Schneider says it is East Germany’s best bet to “safeguard reliable energy prices for households and companies and increase competitiveness in the medium to long run.”

Eastern state leaders, who hail from the CDU, the SPD and the Left Party, appear to have the same view. Alarmed by the strong showing of the populist parties at the EU elections, the state premiers warned already in June that the state elections will be about “safeguarding what we accomplished” in energy and climate policy and that a successful transition would be a key instrument for keeping voters in the East away from supporting extremist forces. Earlier in the year, the states launched an initiative to coordinate their efforts and make the East “the nucleus of a sustainable German hydrogen economy.”

Coal exit schedule will not be undermined - plant operator

Ahead of the EU elections, nearly half of all companies in Germany publicly positioned themselves against the AfD, fearing that the far-right party would damage the country’s reputation as a business location, increase difficulties to attract international talent and deliver lasting damage to its political culture, found economic research institute IW earlier this year. In the eastern states, many companies, especially the more locally rooted small- and medium-sized ones, are wary about taking an explicit stance against the AfD. However, a survey by public broadcaster ARD among 200 companies in Saxony and Thuringia – of which only 30 provided an answer – found that more than two thirds fear the impact of the AfD’s success on their own business and on the local economy; the AfD has repeatedly accused ARD of towing the government’s line and wants to cut the network's state funding. One in five respondents to the survey said they expected job losses should the far-right gain power, three quarters fear an exodus of skilled workers in a region that already suffers from labour shortages and 90 percent a loss in reputation for the label ‘Made in Germany.’ The AfD refuted these concerns to ARD, arguing high taxes, bureaucracy and “the policies of the ‘old parties’ make our country unattractive.”

Yet, a more recent IW survey of about 900 companies in the East led to similar results: Behind closed doors, many business owners there said they also fear a strong AfD in their states. Sixty percent of respondents said they are worried what a success of the party will mean for EU cohesion and the common currency, the euro. Only 13 percent of companies in the East said they expect the AfD to bring economic benefits for them and 29 percent said they agree with at least some of the far-right party’s positions – compared to 22 percent in the West. Given the relatively stronger showing of the AfD in polls, the poor results for the populists in the content-based survey had been “a surprise,” the IW said.

Energy company LEAG – the biggest employer in the vast coal region Lusatia, which straddles parts of both Brandenburg and Saxony – shares concerns about the populists. “This worries me greatly,” said LEAG CEO Thorsten Kramer in an interview with manager magazin. Kramer said that “radically damning” the AfD would not be of help when people are heavily influenced by concrete fears about inflation and economic stability. However, the prospect of an AfD that gains a say in policy making, even at the local or municipal level, would compel the company to defend its support “of democratic values and an open society,” the manager said. He added that the company’s plans to end its coal power activities in 2038 would by no means be affected even if the AfD gains power. “The path to renewables can no longer be blocked,” Kramer argued, adding that the company’s transformation, illustrated by its participation in Lusatia’s bid for becoming the EU’s first ‘Net Zero Valley,’ is an economic necessity. “Most people in the region have understood this by now.”

The AfD and the BSW have different plans: the party manifesto analysis by research institute RLI concluded that both parties scored markedly worse than all other major parties with respect to key indicators for effective emission reductions and climate friendly economic transformation policies. Energy policy and climate measures were identified as influencing voter decisions in all three states, with issues such as Germany’s coal phase-out, the expansion of renewable power installations, the transition in the heating and transport sectors and the costs of carbon pricing all playing an important role for many people in the region.

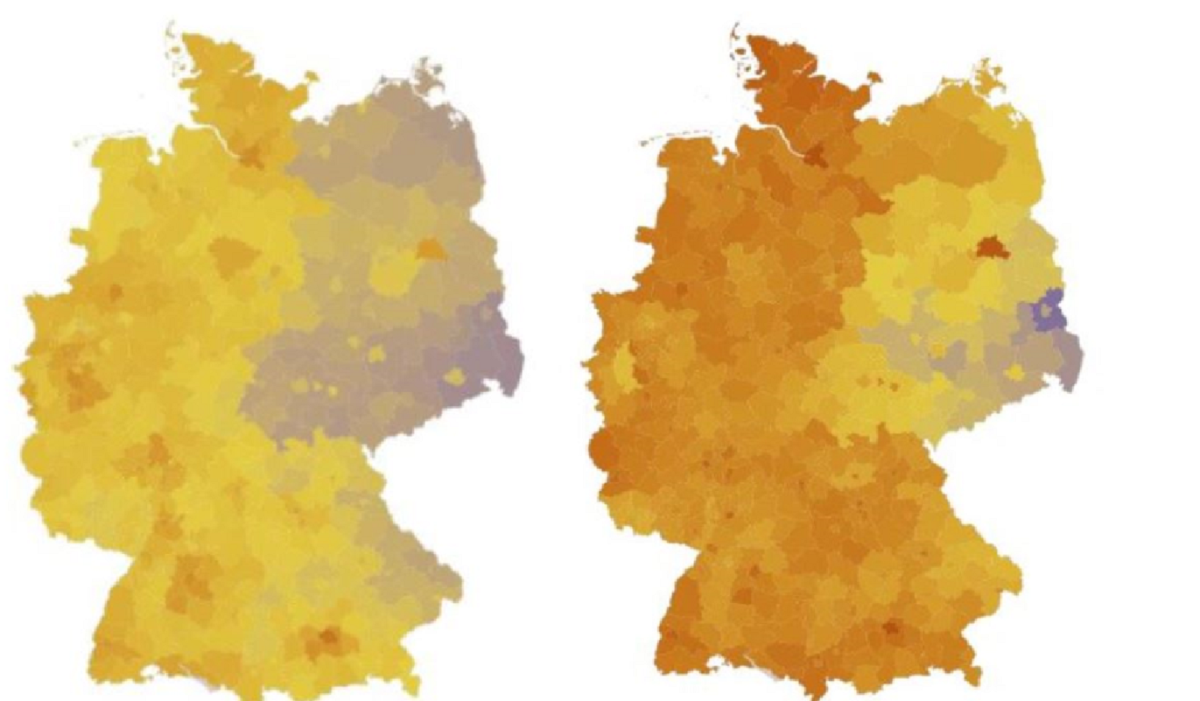

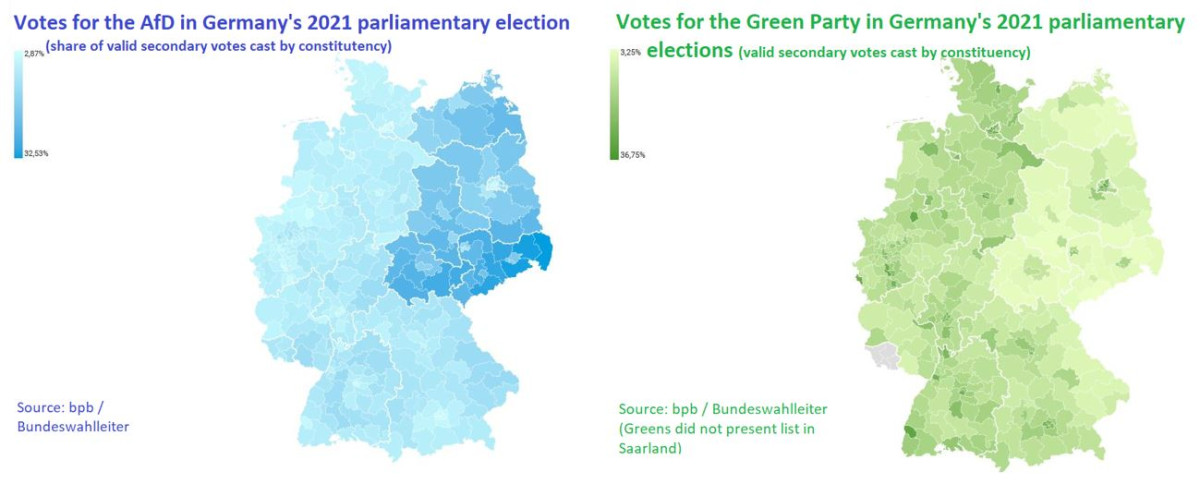

A study on regional attitudes towards climate policies in Germany carried out by the government-backed Ariadne research project for the years between 2017 and 2021 found that, in general, many measures enjoy more support in more densely populated regions and cities. It also showed that East Germans on average tend to be more sceptic when it comes to concrete and often costly steps for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon pricing, the phase-out of combustion engines or a levy on the climate impact of buildings. A perceived injustice regarding the distribution of costs and benefits as well as a generally higher distrust in public institutions were found to be factors further reducing individual readiness to act, both of which are more widespread in the East.

How can this rejection of a promising economic future based on low-carbon technologies by people in eastern Germany be explained? For political scientist Manès Weisskircher, who researches the nexus between the political far-right and the rejection of climate action at the TU Dresden, the strong support for both revisionist parties is due to the GDR’s legacy and the neoliberal transformation of the region after reunification. The researcher added that individual economic stability is regarded as more precarious in the East, there are fewer experiences with immigration and political and social elites are often perceived as originating from the West. Disappointed by unmet promises of prosperity in the 1990s, many people distrust that the promised benefits of transitioning the energy system will arrive this time, he argued. “All of this is fertile ground for new political actors that challenge the established parties.”

An analysis by research institute ifo Dresden found that voters of the AfD and the BSW often are motivated by a feeling of disadvantage and fears of rapid economic and social changes. “However, the support cannot be traced back to an objectively worse economic situation,” the researchers said after reviewing voter motivations at the European elections. “Populist parties find support in regions with a high share of older voters and where people have little confidence in the future,” meaning that a subjective feeling of discontent had a much greater impact than measurable economic factors, the ifo said.

Weisskircher added, however, that “a majority of people in eastern Germany are in favour of expanding renewables,” pointing out that “the devil is in the detail.” Rejection often comes with reasons at the local level. While the AfD is clearly exploiting existing grievances to undermine the energy transition, specifically regarding wind power in rural parts of the East, the BSW’s position is still being developed and appears to be more nuanced, Weisskircher said. While the BSW’s Wagenknecht has ruled out a coalition with the AfD – and the Green Party – in the eastern states, “the BSW could become an acceptable coalition partner for both the CDU and the SPD at the state level – not at the federal level,” the researcher said.

This is already weakening the AfD’s position, as forming a state government without them would be possible even if they become the strongest force in the regional parliament. Centrist parties will thus be able to pursue their policy of rejecting any close cooperation with the AfD, he argued. However, the political scientist added that the AfD can still throw sand in the gears of climate policy from the opposition ranks: “Climate policy measures are usually very complex, laden with internal contradictions and sometimes are not prepared in an optimal manner by government actors. This opens a strategic opportunity for the AfD to engage in fundamental opposition and make parts of the public more sceptical towards important and urgent political measures.”

Too cheerful picture of the energy transition in the East risks irritating voters - NGO

Environmental protection in the eastern states has in general already become more challenging due to the AfD’s influence, said Daniel Rieger, head of climate and environmental protection at environmental NGO NABU. “Dealing with newly elected AfD representatives at the local level looks set to become a massive challenge for our work,” Rieger told Clean Energy Wire. NABU’s local groups, of which membership numbers and outreach in the East today are much lower than in the western states, rely on the willingness of mayors and regional authorities to implement environmental protection projects. “And it is only a matter of time until some of these people will be AfD members. Given the general incompatibility of our positions with those of the AfD, this could become very difficult,” Rieger said.

The challenge will then be to find appropriate ways for nature protection without normalising a right-wing extremist party or losing precious time in our fight against a range of environmental challenges in the eastern states, the conservationist said. For NABU, the main concerns are water resources in Germany’s driest region (which also play a key role in carmaker Tesla’s continuing legal woes in Brandenburg), the legacy of GDR agriculture industry and its lasting impact on biodiversity as and the future of the massive former coal mining areas, where rewilding will be a multi-generational task. Instead of addressing these regional problems, “the AfD has sought to cover the area of environmental policy under the term ‘homeland protection’ to suggest that the conservation of ecosystems is part of their programme,” Rieger said.

To this end, the far-right party has even sought to exploit NABU’s good reputation by using the NGO’s logo and taking some of its positions out of context in its own campaigns – regarding onshore wind power, for example – to lend legitimacy to its criticism of the energy transition and climate action. “We have taken legal steps against these efforts and must be wary of AfD supporters that try to infiltrate our regional NABU associations,” he added. Rieger cautioned that policymakers painting an overly cheerful picture of the energy transition in the East risk irritating voters: “The buildout of renewable energy sources has surely worked well in East Germany if you only look at the numbers. But this has come at a price,” he argued.

Not only were environmental standards often overruled, many locals believe that the fast installation of large solar and wind farms has happened without their consultation and in a way that hasn’t benefited them. “Many people feel that profits go to anonymous investors, often hailing from the West, while they are left with the installations in their neighbourhoods,” said Rieger. At the same time, the lack of grid capacity means a lot of the energy produced in East Germany cannot be transported. People living in the area face higher grid fees due to the required grid management costs when balancing supply and demand. “All of this puts a question mark behind the energy transition’s success in East Germany,” added Rieger.

Especially energy costs continue to occupy voters’ minds in the East. After a recent analysis by price comparison website Verivox found that households in eastern states pay much higher electricity prices when adjusting for purchasing power, a survey by energy company Octopus backed the conclusion that this is fuelling a feeling of disadvantage and unfair cost distribution there. Four out five people in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg said the power prices they must pay are too high – and two thirds said that energy costs would influence their voting decision. In Thuringia, about half of respondents said they would curb climate action measures to achieve lower prices. “The East is boiling when it comes to high costs for power and heating,” said Octopus Germany CEO Bastian Gierull. He warned that people could perceive emissions reduction as “a luxury” if no way is found to bring down energy prices for citizens in the East – where much more renewable power installations are installed per capita.