German Greens refuse to reveal red lines in coalition talks

Clean Energy Wire: Which climate and energy policy steps will be given the highest priority if the Green Party enters government?

Lisa Badum: Rapid steps to save CO2 emissions as quickly as possible. There are many measures that will require negotiations, but speed is of the essence. We also need steps that constitute an important signal of where we're headed – for example ending construction of the contested motorway in central Berlin. We also want to create new environmental protection areas such as national parks – this is another highly visible measure, and it's not even much contested. There are also many steps that can be taken quickly to improve defences against floods with new incentives from the federal government, such as creating retention areas and so-called sponge cities that can absorb much more water.

Where do you expect the biggest hurdles on Germany's path to climate neutrality?

It's not a secret that the path to climate neutrality will be much harder for certain sectors than for others. Obviously, it's much easier to exchange coal power plants with renewables than making all our buildings climate-neutral. This is partly because the preconditions vary greatly – rural areas vs cities, existing heating infrastructures, and so on. Moreover, landlords decide for themselves when a renovation makes sense. This cannot be dictated by the state, and we don't even want to. But at least it would be a start to stop subsidising gas boilers, end the installation of oil heating systems, and reform financial support that is granted on the basis of efficiency standards dating back to the last century, for example. Another area that doesn't receive nearly enough attention is agriculture. But lowering emissions here will require a reform of European agricultural policy, which won't happen overnight. Transport is also a tricky sector. Everybody wants to be mobile, has their preferences in day-to-day life, and the issue becomes very emotional. Most people find it really hard to re-imagine mobility in a totally new way.

What's your opinion on climate activists standing in local elections in competition with the Greens?

Highlighting the issue of climate protection will benefit everyone involved in this issue, and society as a whole. We need drive and ambition. On the other hand, voters will have to take into account that they might prevent a progressive coalition if a few percent of the votes go elsewhere. In the recent state elections in Baden-Württemberg, for example, other coalitions would have been possible if fewer votes would have gone to extremely small parties. This is our message to the voters – but of course, they have to decide for themselves.

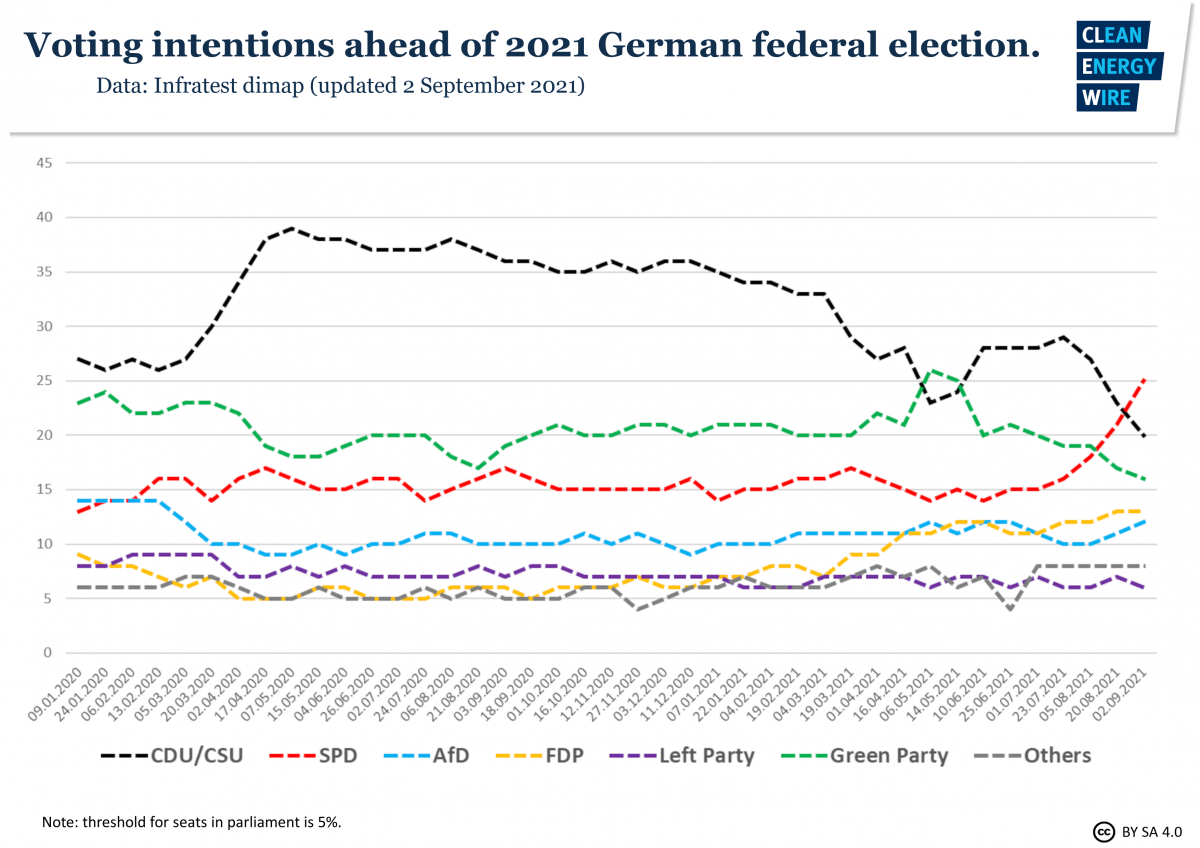

Current polls suggest that the elections on 26 September will be followed by lengthy coalition talks. Where do you expect the biggest stumbling blocks?

It's always extremely difficult to forecast negotiations. Obviously, the fewer votes we get, the harder the negotiations will become for us. This is why we urge everyone who wants social and ecological policies to vote for us instead of casting their vote for someone else for strategic considerations. During my time in parliament I have acutely felt the consequences of a single election day that fixes majorities for four years. Over the last four years, we were the smallest parliamentary group, which had significant effects on what we could achieve. Every additional vote is an additional lever.

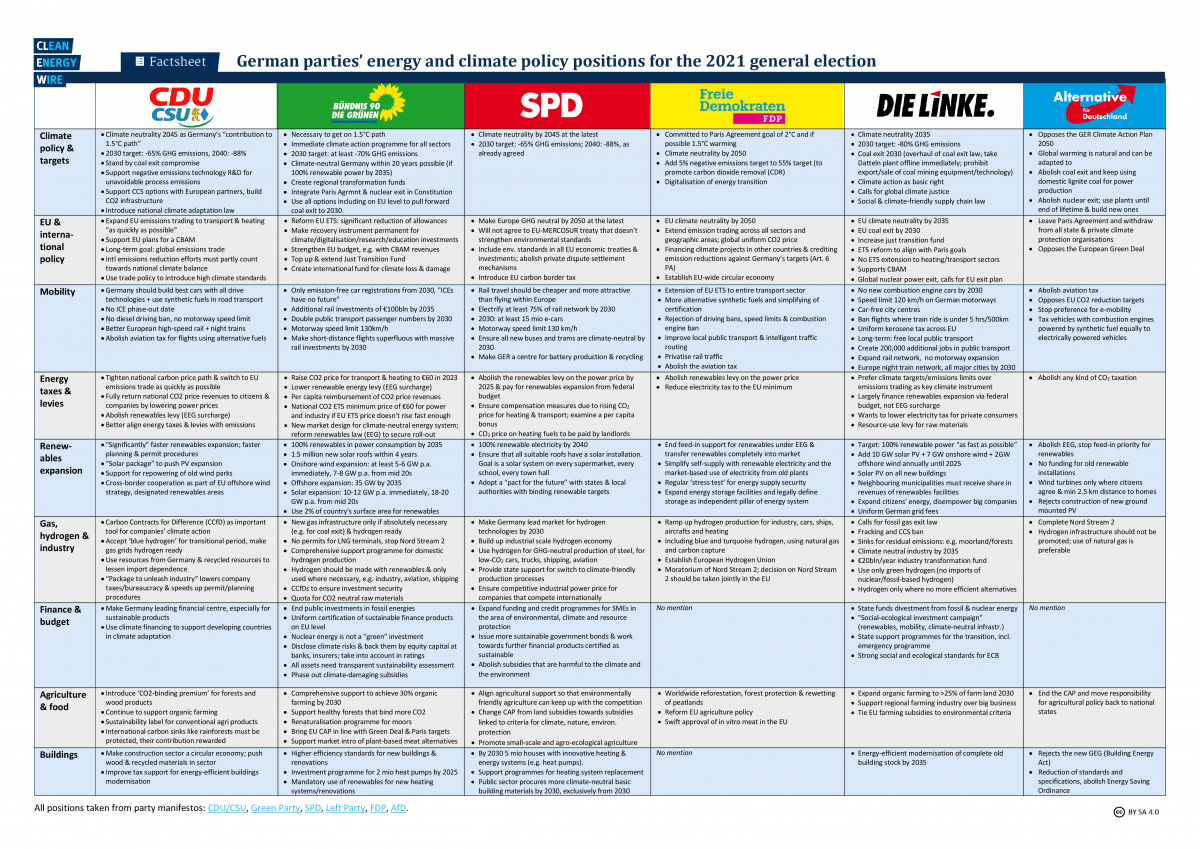

There are considerable differences between the party programmes, but we can also find similarities. For example, everyone believes that hydrogen will be a crucial step for emission reductions. Starting from there, we can also talk about how we get to green hydrogen, where to use it, and how much renewable power will be required to make sufficient amounts to get anywhere near a real hydrogen economy. I believe we can find compromises with other parties on these issues. But to highlight a crucial difference to other parties: It's simply a lie to suggest to voters that everything can stay the same and nothing has to change for consumers or industry on the way to 100 percent climate neutrality. We very much hope that other parties will eventually understand that it won't work like that.

Are there certain policy positions that you would describe as a red line in coalition negotiations?

I can't define red lines in this interview, as it would be strategically unwise to reveal negotiation tactics beforehand. But everyone can calculate that there are different ways to achieve the climate targets, and there are certain sectors where we can cut a lot of emissions in a short period of time. If someone has other ideas where those cuts can come from, we're open to discuss that, but we haven't found any alternative proposals in the other parties' programmes. This suggests there are certain measures that will have to be taken, such as an earlier coal exit.

Emissions trading reform will make Germany's 2038 coal exit date obsolete

Speaking of the coal exit, do you think the market alone will ensure an earlier exit via higher CO2 emission prices, or do you plan to change the coal exit law?

The market will only exert real pressure if we reform emissions trading to reduce the amount of allowances to make them more expensive, and it can only work if we roll out the necessary amount of renewable power. The European Commission has tabled a proposal for emissions trading reform, which could have been even more ambitious, but it implies a Europe-wide coal exit by 2030. We believe that the emissions trading reform will make Germany's 2038 coal exit date obsolete.

Are you concerned that a faster coal exit could endanger the plans for a just transition?

The term "just transition" is often bandied about in this context but I believe "just transition" also means keeping in mind people elsewhere in this world who experience drastic environmental change that is totally beyond their control, for example on the Fiji islands. This is also a form of structural change and we have to show solidarity. There is an overlap in the interests of those affected and people in Germany, including coalminers, who want to make sure their grandchildren have a future. The German coal exit is extremely well financed, with generous support for the regions and the employees.

Do you think we will need a similar support programme for the transition in the car industry?

I wish we had the same amount of money left to cushion the transformation of the car industry, but keeping the dimensions in mind – 1.5 million employees will be affected, compared to 10,000 in the coal industry – we simply can't afford it. At least there is a vital difference in that the industry will remain in place because we don't want to exit car production, we just want to transform it. This makes it more complicated, and this is why we call for transformation funds and councils to support the shift. I'm from a car supplier region myself, and I see that job cuts are often blamed on climate policies, when in fact digitalisation is the real culprit, or multi-national companies transferring production to cheaper locations.

Germany's climate policies, such as the coal exit and financial support for renewables and electric cars, have a reputation for being very expensive. Do you think we must make it more cost-efficient?

First of all, I believe that climate damage will become very expensive indeed if we don't do enough to fight climate change. Also, many expenses clearly do not deserve the label "climate protection investments" – for example, the compensation payments to coal power plant operators. Real climate policy investments will eventually pay for themselves and create jobs. We need to shift public expenses into the right direction, and summon up the courage to invest in the future.

Do you think the parties – including the Greens – are honest about the true costs of climate protection? Many policymakers appear to suggest that consumers and companies will be barely affected.

The devastating floods in Germany have shown the consequences of neglecting investment in flood defences, and what happens if we don't take the climate crisis seriously. At some point, every voter must ask themselves: 'Do we want to stumble from one crisis to the next? Or shall we start serious prevention? And which party has the best concepts for this approach?'

Many people still have to overcome an internal dilemma – they want change and are in favour of action against the climate crisis, but at the same time they don't want to be personally affected – I think we all know this feeling. They must understand that the way to overcome this dilemma is to change the laws so they give a financial incentive for climate-friendly and ethical behaviour. For example, if you decide to eat a steak, you should be able to be confident that it has been produced sustainably and doesn't violate animal welfare, instead of castigating yourself constantly. We are trying to propagate this philosophy – to hand over responsibility to where it belongs. But this requires people's trust – and their votes.

Many experts believe Germany will need carbon capture and storage (CCS) to decarbonise industry, and countries such as Denmark and Norway are pushing ahead with projects, while the technology is de facto illegal here. What's your position on this topic, which is not even mentioned in the Greens' election manifesto?

The German states where CCS could be possible have all decided that they don't want it because citizens are against it. I think we have to accept that the will simply isn't there. But more importantly, from an economic perspective, it's not relevant and doesn't make sense. There are no companies here who apply it because the technology is extremely expensive. I don't think a discussion about whether we can store CO2 in Denmark or Norway will help us at present. We have to put the focus on cutting emissions now and discussions about CCS are a distraction. They also involve the danger of people saying, "Well, we're not in a hurry to cut emissions because we can just store CO2 below the North Sea later." It's a chimera – a solution that doesn't exist today. So let's focus on the technologies that are available.