Coal and conservatism: How Polish activists push for more climate action

When the Polish government introduced a near-total abortion ban in October 2020, a wave of protests swept the country. Among the 100,000 people who took to the streets in the capital of Warsaw were members of the climate movement. “We were supposed to go hand in hand with the Women’s Strike and our logos were to be placed next to each other,” Piotr Starzewski from the Polish branch of the Youth Strike for Climate tells Clean Energy Wire. “It was an extremely controversial moment within the movement.” After some internal discussion, the activists decided not to join the protests under the banner of the climate strike – instead, whoever wanted to go did so independently. “We did not want to join the openly anti-government protest as we wish to maintain diplomatic relations,” Starzewski explains.

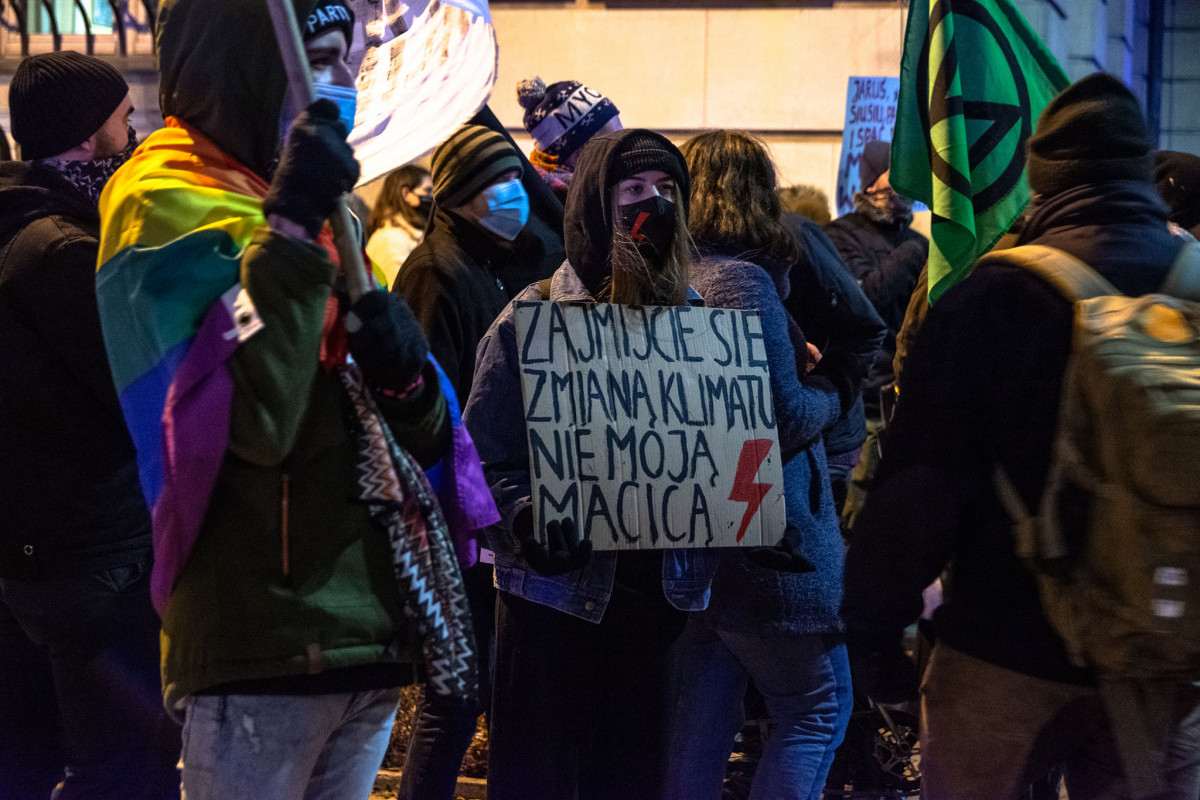

Other climate action groups such as the Polish branch of Extinction Rebellion and the local organisation Camp for Climate participated openly in the protests, their logo-emblazoned flags waving next to those of feminist and LGBTQ activist groups.

These activists’ participation in the women’s protest did not help the climate agenda, says Mateusz Piotrowski, a member of the Polish branch of the Global Catholic Climate Movement. “Among conservatives, there is certainly a fear that the climate issue may be accompanied by a different ideological agenda. This hinders our efforts,” he argues. “In Poland, people are and will be conservative. Without them, we cannot save the climate, so you have to have them on board.”

A giggle of history

The participation in the protest by Polish climate activists shows the challenge facing the movement right now. It is struggling to connect the progressive ideas of the international climate movement with the conservative values of Polish society. “We have already dealt with this problem once before,” says Przemysław Sadura, a sociologist from the University of Warsaw and the curator of the Krytyka Polityczna Institute, who has led research on the energy transition in Poland and on changes in the climate attitudes of Poles throughout the pandemic.

In the late 1980s Poland’s ecological movement had the biggest public support in its history and made some significant achievements, such as stopping the construction of a nuclear power plant in Żarnowiec, Sadura explains. However, the movement collapsed after a dispute over whether to vote in favour of banning abortion. “Feminists turned off, and for the pro-lifers, support for legalising abortion was an insurmountable limit,” he says. “Thus, the most promising political initiative of the 1990s split and fell apart. It would be a giggle of history if we got stuck in such discussions again.”

The movement didn’t manage to establish a political party aftewards, and since then the subjects of climate and ecology have been introduced to the Polish political debate from the outside: by the European Union, international parties and organisations such as Greenpeace and the European Green Party. These narratives were not always adapted to Polish society and its values. This is the main reason why they haven’t receive bigger support. Today, the debate on climate in Poland is still entangled in the conflict between political right and left.

Coal and conservatism

When it comes to climate policy, the ruling right-wing nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS) seems set to maintain Poland’s dependency on coal – or at least for the foreseeable future. The country still produces around 70 percent of its electricity from this highly climate-damaging fossil fuel and subsidises it heavily – PLN 8bn (€1.75bn) of public funding is set to go to fossil fuels in 2021. Poland has not committed to the goal of climate neutrality by 2050, unlike all other EU member states, and the government only foresees the closure of the last coal mine by 2049, symbolically adjusted to the European date. A recent document outlining Poland’s energy strategy until 2040 has been described as “disappointingly unambitious” by German energy think tank Ember. Even among political opponents of the ruling party PiS, from far right to the political left, no party has a plan for a coal phase-out before 2035.

Despite the government’s reluctance to reduce emissions, many Polish people are of the opinion that climate change should be treated as a priority. A recent poll from research centre PEW shows that 53 percent of Poles considered climate change “a very serious problem” in 2020, compared to 19 percent in 2015 and 31 in 2010. Two-thirds of respondents in 2020 also claimed that the government does too little to combat climate change. This change of opinion is reflected in a political shift around the climate issue. “There is a difference between the 2015 and 2019 elections: climate and environmental issues have started to appear in the election programs,” says Sadura. He adds that the increased focus on climate issues does not, however, represent a true prioritisation of the issue: “There is now a belief in the election staff that you need to have something to say about it, but mainly to ‘check it off’.”

The Greta-effect?

Though it is hard to pinpoint what exactly has prompted this change of opinion, the rising Polish climate movement seems to have had at least some part of it. Inspired by Swedish schoolgirl Greta Thunberg, who started a global movement of striking for the climate in 2018, a local branch of youth climate activists arose in Poland. In March 2019, under the name Młodzieżowy Strajk Klimatyczny (MSK), or Youth Climate Strike, thousands of pupils and university students across the country took to the streets to demand climate justice for their generation, climate education at schools and a political response to the climate crisis based on science. Poland also has its own branch of the British direct action group Extinction Rebellion (XR), which was established in February 2019, around six months after the UK movement was founded.

Around 90 per cent of Poles are catholic and the country has a local division of the Global Catholic Climate Movement. It was established in early 2018, just before the United Nations Conference of Parties on climate change (COP24) in the Polish city of Katowice. Instead of protesting on the streets, the Catholic movement, which operates as an organisation rather than a grassroots movement, focuses on climate education and ecological transformation, such as climate-friendly building refurbishment, in around 11,000 parishes across the country.

“The climate crisis must be seen beyond divisions. The point is that no matter who you are, this issue will affect you anyway – this is an important perspective, especially in Poland today.”

Arguably the most radical Polish climate group, both in terms of its demands and methods of using nonviolent civil disobedience, is a movement of Polish origin. Obóz dla Klimatu (The Camp for the Climate) is a group that evolved from the Camp for the Forest, which was established during a protest against logging in the Białowieża Forest between 2016 and 2018. “We have the feeling that we are unique compared to the other climate movements, because we are pushing the boundaries of radicalism,” one of the activists, who prefers to stay anonymous because they feel threatened and invigilated by the police, told Clean Energy Wire. In 2019, the group conducted its first mass civil disobedience action in the area of the Tomisławice lignite mine. “We also fight for the rights of LGBTQ people, we raise topics related to feminism, we talk openly about anti-capitalism, being anti-state and anti-police,” the activist explained.

The anti-capitalist attitude of this group is another rarity in the climate movement. While international climate activists are more open to criticising capitalism, the Polish movement refuses to call for huge economic changes. “I find it difficult to support the anti-capitalist slogan,” says Starzewski from MSK. The Polish activists speak about sustainability, standing against consumerism or greed, but not the system itself. Critical reflection on the capitalist system and its relationship to the climate crisis, while not that controversial in Western Europe, remains rather marginal in Poland.

Political influence

“In 2018, we were still in a state of deep denialism of climate problems in Poland,” says activist Patryk Kowalczyk from XR Poland. “When I started at XR, the minister of energy said that CO2 in the atmosphere is good because trees grow faster, and the government was planning to build a new coal-fired power plant Ostrołęka C.”

“Activist movements have played a large role in bringing climate to the mainstream of public debate,” says Maciej Józefowicz, spokesperson for the Polish Greens. “Thanks to the activities of the Youth Climate Strike and Extinction Rebellion, Poles were able to learn that the climate crisis is not only a challenge that worries scientists, but the most important problem for young people around the world.” Bartek Wejman from the new catholic and conservative party Poland 2050, which demands climate neutrality by 2050, agrees that it was activists and scientists who brought the topic of the climate crisis into public discourse in Poland. “Social pressure is an indispensable element of politics,” he adds.

However, the effectiveness of the climate movement in Poland is not just down to the ‘Greta Thunberg effect’, says Sadura. He underlines the influence of European and global political discussion about climate change in the last few years, such as the talk around implementation of the Green Deal and the Paris Agreement. At a local level, pollution issues had already come to the foreground in Poland shortly before Greta came into the picture. “Anti-smog movements caught the topic of ecology and climate in a way that was important to people. They showed that air quality in Poland is badly neglected compared to Europe and other OECD countries,” Sadura tells Clean Energy Wire. “Paradoxically, Polish smog movements have done more for the cause than Extinction Rebellion or the Climate Camp, because the average person equates the climate and the environment, and they have shown that ecological problems concern the quality of our life, health – and us directly.”

Focus on environmental issues, rather than climate change, has been a strategy for the Catholic organisation as well. Whereas on a global level the group operates under the name “Catholic Climate Movement”, the Polish branch decided to call themselves the “Catholic Movement for the Environment.” According to operation manager Magdalena Kadziak and programme advisor Mateusz Piotrowski, the word “climate” could, in their opinion, bring a negative association of the cultural revolution some climate activists call for. This, they say, would repeal the conservative part of society that the movement wants to reach.

Climate for all, not just the political left

While climate activists in other European countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany openly call for broad progressive change – including women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, anti-racism and anti-capitalism – Polish activists are more hesitant. While most of them admit that their worldview is progressive, they do not want to be associated with the political left.

“In our country, treating ecology as leftist does not help the cause, in my opinion. Because it is not a ‘leftist whim’, but a threat to life,” says Kowalczyk. "We are committed to attracting conservative people [to our organisation], but with the current polarisation, it is difficult to achieve".

Starzewski from the Youth Climate Strike adds: “The climate crisis must be seen beyond divisions. The point is that no matter who you are, this issue will affect you anyway – this is an important perspective, especially in Poland today.”

“If you ask voters, including right-wing voters, they are very concerned about environmental and climate issues. Issues such as combating smog or heat are the concerns for the common good, it mustn’t be politicised,” says Piotrowski. “Right-wing or left-wing ideologisation does not serve the purpose of acting on these issues."

But some activists fear the climate issue may be appropriated by the political right. “As the political leaders started discussing the climate, an opportunity to talk about it as an existential issue was immediately wasted and it got mixed up with nationalist rhetoric,” says the anonymous Camp for Climate activist. “Suddenly, we are talking about Polish national parks and Polish families being at risk from the climate crisis.” For the climate camp movement, it is not a national issue but a global one, they add: “Our motives cannot be narrowed down to national categories.”

Sadura argues that the fact the subject is no longer owned by the political left, but has become more universal, is a good thing. He makes the comparison to the German energy transition, which has enjoyed broad public support. “The Energiewende in Germany was not a programme won and implemented thanks to the most radical parts of the Green Party, not at all,” he says. “To a large extent, it was a grassroots movement based on prosumer cooperatives from local communities. In Germany too, much could not be done without conservative communities.” The fact that climate issues have moved to the political centre in Poland is, in the end, good news for climate action, he concludes.