New cable between Germany and UK advances Europe’s integrated power system

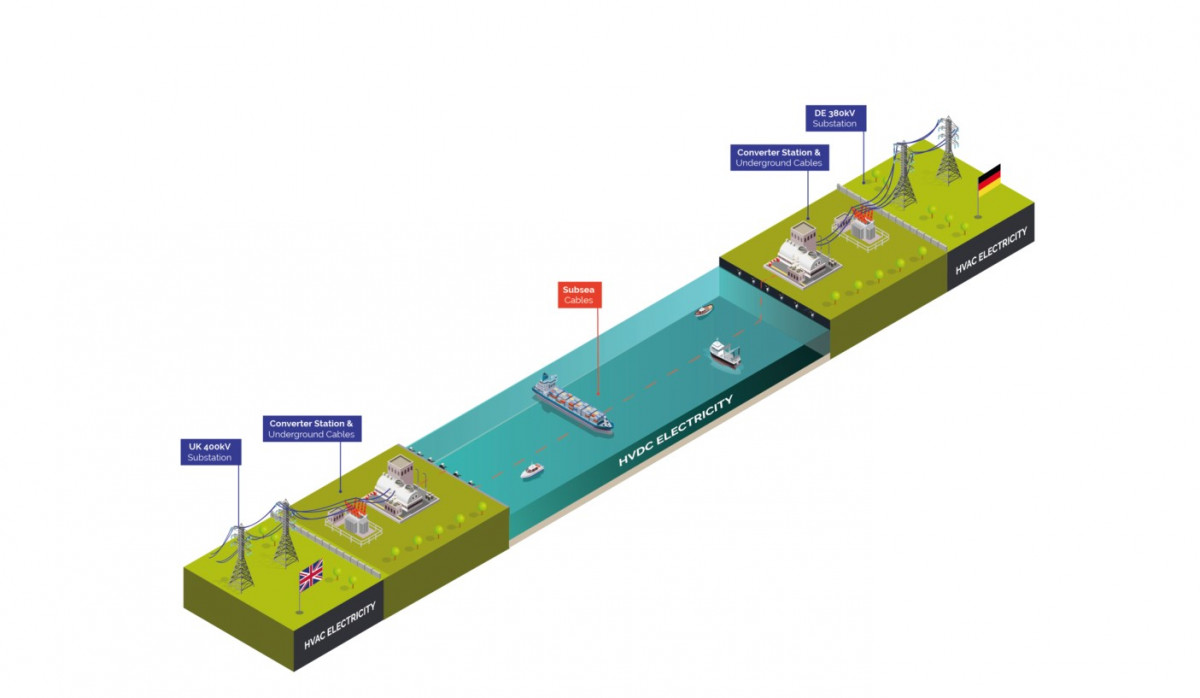

By the mid 2020s, Germany and the UK could be connected by the first ever direct power cable link between the two countries. The direct current subsea cable, connecting the Isle of Grain in the UK with Wilhelmshaven in Germany is one of the first privately financed interconnectors in Europe – but also has the backing of the two governments, both of which are stressing the need for power system integration as shares of fluctuating renewable power sources are increasing. Meeting the UK prime minister Boris Johnson in July 2021, German chancellor Angela Merkel signalled her support for the interconnector, saying it would help both economies to decarbonise more rapidly.

Construction of the “NeuConnect” interconnector could begin next year, offering 1.4 GW of capacity for electricity to flow between the two markets for the first time. The line will provide an effective outlet for surplus wind energy from northern Germany, helping to reduce bottlenecks resulting from weaknesses in Germany’s North-South domestic grid. From the UK perspective, the new interconnector will provide a valuable source of cheap green energy coming from northern German wind parks. “It will allow our energy grids to share excess power – making sure renewable energy is not wasted,” Merkel said in her statement in July.

For the UK government, the cable forms part of a longer-term ambition to become a net exporter of electricity by the 2040s, rather than a net importer as is currently the case. At the moment the UK has just 6 interconnections (2 with Ireland, 2 with France, 1 with the Netherlands and 1 with Belgium) with 6 further projects under construction or confirmed. Germany has 54 and 8 in advanced planning. The UK’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy is forecasting a rise from 5.7 GW interconnector capacity (the current level) to 18.9 GW capacity by 2040. Wind production capacity is projected to rise by more than 20 GW over the same period, creating surplus energy for the UK to export.

The construction of cross-border interconnectors is an important element of Europe’s decarbonisation strategy. The UK and Germany have both made it easier for private investment to enter the interconnector market. “Now the project financed model of delivery has been set, we are likely to see more interconnectors developed this way in the future,” a spokesperson for NeuConnect said. As both the UK and the EU are pursuing climate neutrality goals in the middle of the century, the process of integrating Europe’s energy grid has widespread support and promises by facilitating the transition to renewables and lowering energy costs for consumers, proponents argue. Getting there, however, brings with it political as well as technical challenges and not all governments and citizens are enthralled by the idea that they will have to rely on power generated in other countries and that new power lines need to be build.

Germany and UK amend laws to allow for privately funded interconnectors

Almost all of the existing interconnectors in Europe have been developed by transmission system operators (TSOs) such as TenneT in Germany and National Grid in the UK. NeuConnect, however, is a ‘new entrant’ into the energy market. It is one of the first project-financed interconnectors in Europe, meaning that the three major investors - Meridiam, Allianz Capital Partners and Kansai Electric Power – have put money in upfront and will recoup their investment from future revenues. This business model has been made possible by changes to both German and UK law and regulatory frameworks. Up til now, the development of project financed interconnectors has been challenging because the regulatory frameworks across Europe typically favour TSOs.

Project financed interconnectors like NeuConnect are still eligible to apply for public funding via the ‘Connecting Europe Facility’ grant, if they have Project of Common Interest (PCI) status. The German-UK interconnector has been awarded PCI status and will receive grant funding for project-specific aspects on the EU side. Post-Brexit, this funding is not available on the UK side.

New interconnectors to help Europe to achieve more grid and renewables integration

The UK’s National Grid is keen to encourage more project-financed interconnectors and has 4 (including NeuConnect) under development. The UK National Grid considers that private investment is in the interests of UK consumers, promoting competition in the interconnector market, reducing costs and speeding up construction of new links.

Ed Vaughan, energy strategist at Carbon Tracker, told Clean Energy Wire “we’re likely to see a bigger role for structured project finance for interconnectors in the near future”. On the other hand, a spokesperson from the EU Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) cautions that many European regulators may be less enthusiastic than the UK about opening up the interconnector market to private investment because of the risk and regulatory challenges this may bring. Germany’s energy regulator The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA) told Clean Energy Wire that “proposed interconnnector projects are only approvable if there is a need for them and clear benefits from an energy economy perspective. Business models of project promotors are not considered in the BNetzA’s analyses.”

Whatever the financing and regulation arrangements may be, there is widespread agreement that interconnection is essential to enabling efficient renewable electricity markets. As European countries are pursuing net-zero emission targets, many will rely heavily on fluctuating power sources from wind and solar installations. Only cross-border interconnectors will offer the necessary flexibility. When energy generation is low in one country, interconnectors make it possible to import power immediately from other countries where there is a surplus. This not only makes the whole electricity market more flexible but also leads to cheaper prices for consumers, argues the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E). “The benefits for Europeans of a fit-for-purpose network with the right investments in the right places – in terms of electricity prices, continued access to electricity and completion of climate objectives - far outweigh the necessary efforts which will need to be mobilised in the next decades for its construction,” they said.

ENTSO-E estimates that, across Europe, a further 93 GW increase in cross-border grid capacity will be needed over the next two decades to support and enable the transition to renewables. Back in 2014 the European Council set targets for members states to build interconnection capacity equal to at least 10 percent of their installed electricity production by 2020, rising to 15 percent by 2023. As of last year, however, only 17 of 28 member countries were on track to meet their interconnector targets.

Further integration seen as beneficial for all – but “energy sovereignty” ideal is hard to shake

In order to achieve these ambitions for grid expansion, there is an urgent need to find solutions to the technical and market-related problems that have emerged as a result of increasing cross-border grid integration, in particular flexibility products to help manage volatility.

There are political challenges to integration too. Highlighting the importance of interconnectors, chancellor Merkel and her Norwegian counterpart Erna Solberg were both present to officially launch the first Norwegian-German subsea power cable “NordLink” in 2021. After a construction time of 5 years, excess German wind power can now be transferred into the Norwegian grid or their pumped hydropower facilities and the other way around.

Nevertheless, Professor Indra Overland of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs is frustrated that many of his fellow Norwegians view energy integration with suspicion and would rather keep surplus energy inside Norway. “Some in Norway are promoting energy sovereignty and market protectionism to help bolster nationalist, anti-EU sentiment,” he told Clean Energy Wire.

“Some in Norway are promoting energy sovereignty and market protectionism to help bolster nationalist, anti-EU sentiment."

Professor Overland stresses that further integration of the energy grid is beneficial at all levels, supporting decarbonisation, low cost energy and international cooperation: The fundamental difference between the old world order of oil and gas and the new order of renewables, he said, is that every country has the capacity to generate renewable energy. "As a result, we will no longer see the same dependence on resource rich countries as there has been historically." Instead the new landscape "will likely involve more symmetrical relationships between different prosumer (producer-consumer) countries". "Where there is competition and potential for winners and losers it’s in the development of technology and manufacturing, not in possession of resources," he said.

Charles Moore, European research lead at UK climate and energy think tank Ember, cites the example of Czechia in making the point that some countries are very reluctant to allow themselves to become net importers when they’ve historically been net exporters. “Czechia is well interconnected with its neighbours,” he told Clean Energy Wire. “The country is trying to find a route out of coal but the coal commission has argued that if the lignite plants are brought offline too abruptly, Czechia will instantly become a net importer and this is politically unpalatable, regardless of any benefits for consumers.”

"Sometimes states are limiting capacity because they want to protect their own markets; other times, they are protecting their domestic grid infrastructure which may need to be strengthened to enable increased use of cross-border interconnectors."

A spokesperson from the EU Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) says that they are seeing a frequent pattern of countries in Europe deliberately limiting capacity on interconnectors. As of last year, the EU has mandated that all member states must open at least 70 percent of their interconnector capacity but ACER reports that most countries are not yet complying. “Sometimes states are limiting capacity because they want to protect their own markets; other times, they are protecting their domestic grid infrastructure which may need to be strengthened to enable increased use of cross-border interconnectors,” they told Clean Energy Wire.

Opposition from communities faced with new infrastructure “in their backyard”

Aside from the geopolitics of integration, there is also the inevitable opposition that comes from communities affected by big infrastructure projects; laying electricity cables, even if they’re underground or under water, can be highly disruptive to people and nature and there have been multiple examples of local resistance to cable construction, including protests against the Suedlink power transmission line in Germany and against the power line from the Hardanger Fjord in Norway.

In the UK, there hasn’t so far been strong opposition to interconnectors. Those that have been built have all connected to existing coastal power infrastructure and impinged little on communities. More opposition may emerge as interconnectors are built on land, along with more onshore wind turbines. One factor that may slow the development of interconnectors in the UK is Brexit. Leaving the European Union means that the UK and European energy markets are no longer integrated. The trade and cooperation agreement that was signed by the UK government and the European Commission in December 2020 lays out a plan for loose volume coupling between the EU and UK energy markets. According to ACER, however, there is slim hope of this new system being implemented by April 2022 when it’s due and this risk may make attracting more projects like NeuConnect more difficult for the UK.

. The ENTSO-E Transmission System Map shows interconnectors between European countries on [entsoe.eu](https://www.entsoe.eu/data/map/) .](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/entsoe-inteconnector-grid-map.jpg?itok=5ut6M-Z7)