Clean batteries key hurdle in carmakers' race to go green

Ambitious climate targets force carmakers to look beyond replacing sales of combustion engine vehicles with electric models. In the race towards truly sustainable mobility, they have started to take aim at cars that are emission-free over their entire lifecycle – from production to disposal.

The first milestone on the road to entirely green cars is lowering the emissions of battery production. The carmakers have begun to tackle this problem by making production much more efficient in so-called gigafactories, many of which will run on renewable power. They are also taking the first steps toward cleaning up other key car components.

"The carmakers are taking emissions reduction and other sustainability issues over an electric vehicle's entire lifetime very seriously – it's definitely more than greenwashing," says industry expert Wolfgang Bernhart, senior partner at consultancy Roland Berger, who has advised carmakers in Germany on this subject.

Bernhart says the companies are keenly aware that neglecting the environmental concerns in the shift to EVs – both in their own production and at their suppliers – would seriously dent their credibility.

"The battery is clearly the current focus of these efforts, because it is the most emission-intensive part of an EV. But the carmakers are also starting to clean up other parts of their supply chains," Bernhart told Clean Energy Wire.

If the carmakers follow through on their promises, EVs could eventually become entirely climate-neutral, says Hans Eric Melin, founder and managing director of London-based consultancy Circular Energy Storage. Pursuing this vision could also turn the automotive industry into a catalyst for emission-cutting efforts in other sectors of the economy, from plastics to steel.

"This transition offers a unique chance to make huge progress on emissions reduction at every stage of vehicles' lifetime – from production to recycling," says Melin.

Heavy burden

EV batteries offer the opportunity to take a huge step towards truly sustainable future mobility, but they currently carry a sizeable environmental burden. Their energy-intensive production means that EVs have caused more emissions than combustion engine models when they leave the factory gate, starting their life with a heavy "emissions backpack." They only become greener than fossil fuel-powered models once they have been on the road for many thousands of kilometres – the exact distance depends on several factors, such as the amount of renewable electricity used to charge them –, partly undermining their claim to be environmentally friendly.

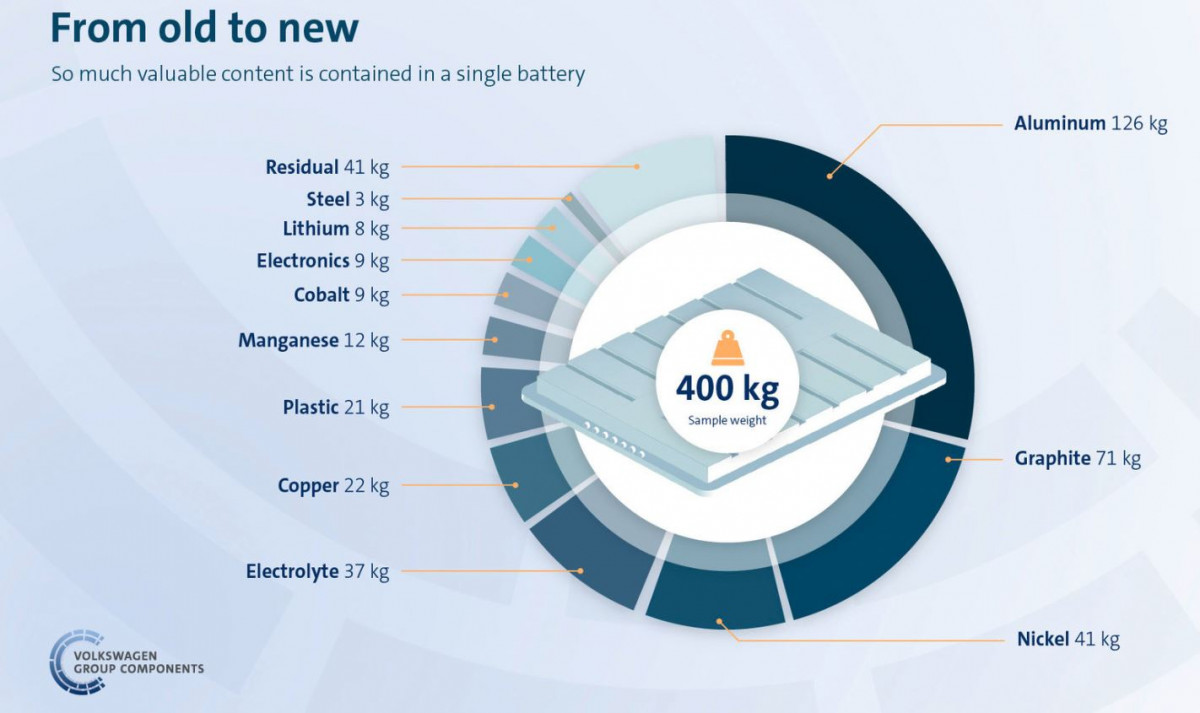

An additional burden on batteries' sustainability is the resources needed to make them. The necessary mining often goes hand in hand with heavy environmental damages. For example, lithium mining is blamed for speeding up desertification around the salt lakes of South America's "lithium triangle." The mining of cobalt, another key ingredient in today's batteries, in the Democratic Republic of Congo is infamous for its inhumane labour conditions, causing huge social costs.

Lighten the load

But this is about to change for the better, as recent industry advances in making batteries more sustainable are set to continue.

"There's already been tremendous progress in making batteries more environmentally friendly," says Lucien Mathieu at green mobility NGO Transport & Environment (T&E), who was lead author of a report on sustainable batteries. "Over the past two or three years, the carbon content has already dropped by a factor of two to three, and we're expecting further progress over the coming years."

The next generation of batteries will already be much greener than the last, thanks to ever larger factories that make production less carbon-intensive. "Producing many more batteries in each plant automatically results in a much higher efficiency," explains Melin. "For example, heat is a very important factor in some stages of battery production, and larger plants use it more efficiently."

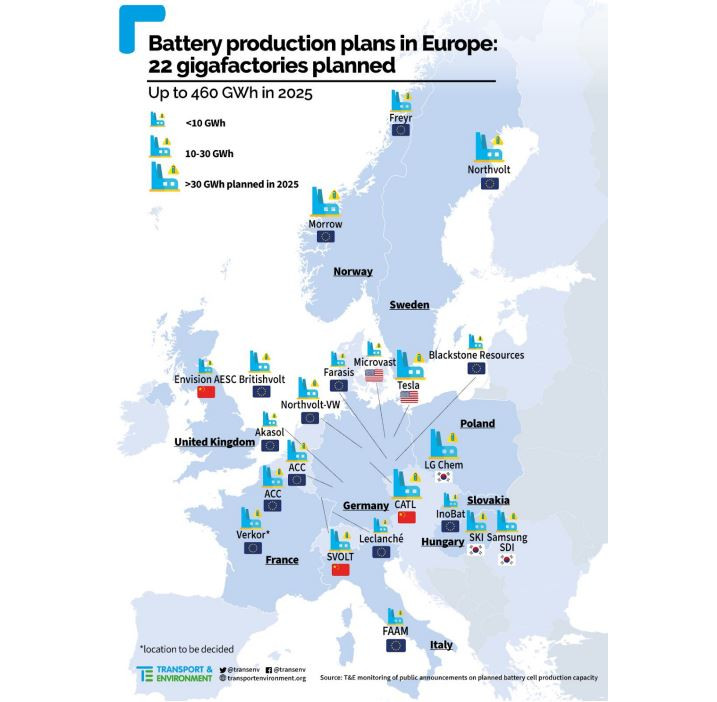

Europe became the fastest growing and largest EV market last year and has ambitious plans to massively scale up battery production. There are 22 large battery factories planned in the next decade in the EU, with total production capacity going from 460 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in 2025, which is enough for around eight million battery electric cars, to 730 GWh in 2030, according to T&E.

Europe wants "only the greenest" batteries

Pending EU regulation to calculate and assess the carbon content of batteries will give the market another push towards sustainability. The European Commission, the bloc's executive, said it wants to ensure that "only the greenest, best performing and safest batteries make it onto the EU market."

"The idea is to either exclude the most carbon-intensive batteries from the EU market or to introduce a transparent labelling system similar to that used for household appliances," explains Mathieu. "With the right policies, we're on track to making Europe a champion of sustainable batteries. Europe probably can't make cheaper batteries than China, but it can make them more sustainable."

New generations of batteries will also require fewer raw materials and less mining. "With battery technology evolving, less raw material will be needed to produce each kWh of an EV battery," according to the T&E report. "From 2020 to 2030, the average amount of lithium required for one kWh of EV battery drops by half, the amount of cobalt drops by more than three-quarters."

Europe is also looking at producing lithium domestically in a more environmentally friendly way instead of relying on imports. Germany's carmakers are in early-stage talks to buy "the world's first fully certified CO2-neutral lithium" from a geothermal project in the Rhine Valley.

New battery technologies resulting in a higher energy density, and production innovations sidestepping energy-intensive steps, could bring down emissions further.

"Real competitive advantage"

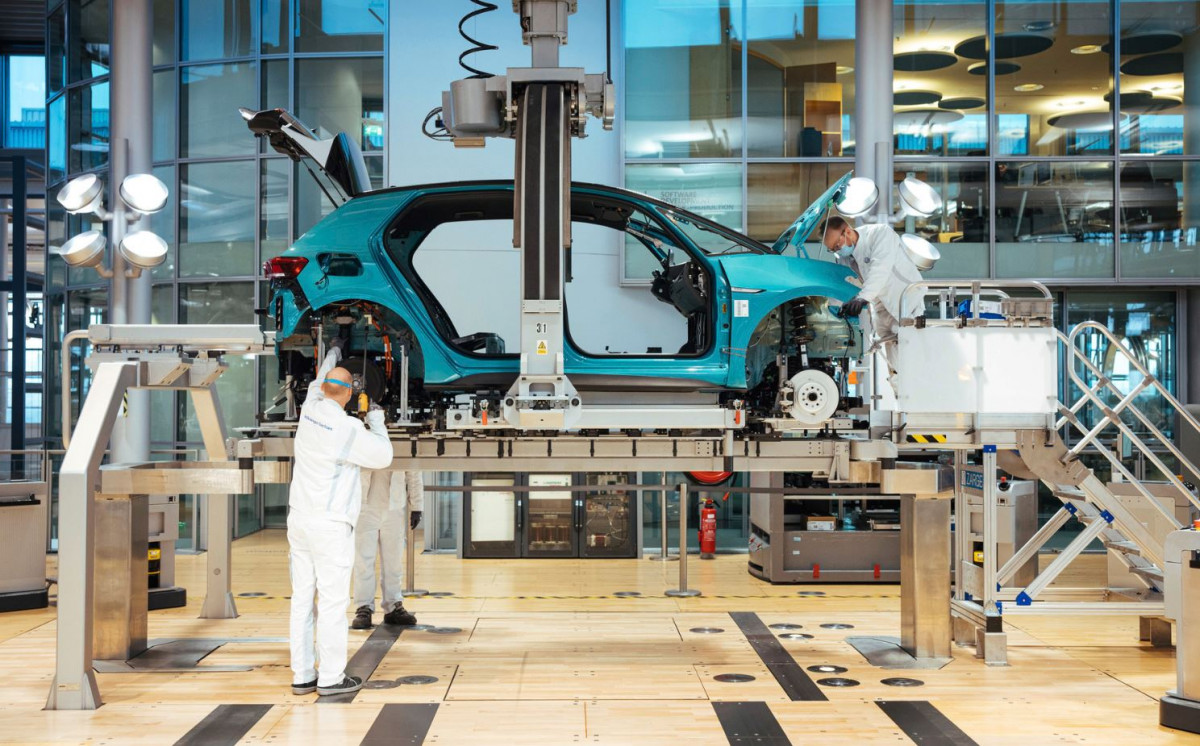

Carmakers are starting to consider cleaner batteries and climate-friendly production a competitive advantage. Europe's largest car group Volkswagen advertises its ID.3 electric model with the use of renewable power during battery cell production and car assembly. It says the entire car reaches buyers CO2-neutral, but it compensates remaining emissions. The company plans six new battery cell factories in Europe with a total capacity of 240 GWh by 2030, some of which will run on renewable power exclusively. The Volkswagen brand says climate protection is not only an end in itself, but also a "real competitive advantage."

“In the future, employees, customers and investors will give preference to those companies which place their social and environmental responsibility at the heart of their business,” according to Volkswagen brand CEO Ralf Brandstätter. “Sustainability will thus become a crucial factor in corporate success.”

Domestic rival BMW also says its mission is to ensure the “greenest electric vehicle comes from the BMW Group.” The company stresses it already sources only green power for its manufacturing locations worldwide, and agreed with suppliers that they will only use renewable green power for producing future battery cells. In its efforts to "achieve the greatest possible transparency in its battery supply chain," BMW has also said it only uses cobalt from sustainable mining.

Other car companies are making similar moves. EV pioneer Tesla plans to build the world's largest battery factory near the German capital Berlin, and was partly drawn to the area by its strong renewable power production. The Californian company has also said it wants to use innovative technology to clean up dirty battery production steps, and also cut cobalt use, in a drive to lower costs.

"Overall, the companies are making good progress in greening vehicle production," says industry consultant Bernhart. He adds that many steps to improve sustainability align with their business interest. "Improving efficiency is very attractive, because it also lowers costs."

But Bernhart also warns that the process will take time. "We can't expect miracles within one or two years."

Climate activists say the carmakers are still not doing nearly enough to fully embrace the transition to sustainable mobility. For example, they point to the German car association's (VDA) determined lobbying against stricter EU fleet emission limits. The VDA also protested against the new government plan to make Germany climate neutral by 2045. The industry often insists it still needs to earn money with highly profitable combustion engine models to finance the shift to EVs.

"From a pure profitability standpoint, every additional day they can sell combustion engine vehicles is a good day," says Melin.

Greening batteries' afterlife

Another key step in greening EVs is improved re-use and recycling. Many EV batteries are already given a second lease on life in stationary storage applications that connect large numbers of batteries.

Partly thanks to these second life applications, the number of EV batteries at the end of their lifetime remains relatively low to date. Carmaker Volkswagen, which opened its first battery recycling plant in Germany, told Clean Energy Wire its current treatment of old batteries is largely limited to "internal sources" like old prototype models. Returns by customers do not play a major role yet, but this is expected to change significantly over the next decade.

In 2030, the volume of old EV batteries could add up to 1.7 million tonnes in the EU, according to consultancy Roland Berger. These could potentially cover up to 30 percent of current demand for valuable materials like cobalt or nickel.

"Recycling of battery materials is crucial to reduce the pressure on primary demand for virgin materials and ultimately limit the impacts raw material extraction can have on the environment and on communities," according to T&E.

Next in line: Green plastics and steel

But sustainable batteries are only part of an increasingly serious industry drive to become truly green. The carmakers have started to exert pressure on other supplying industries, indicating the automotive sector could trigger a climate-friendly shift in other parts of the economy because of its size, and people's willingness to spend heavily on cars.

BASF, the world's largest chemicals producer by sales, said earlier this year it faced growing pressure from carmakers to cut emissions. Chief executive Martin Brudermüller told Reuters clients demanding climate-friendly products had been key to push his company towards pledging 2050 climate neutrality.

"I'm receiving letter after letter from our customers, saying by this or that deadline we need your products to be CO2-neutral," Brudermüller said. "Market pressure is building and investor pressure along with that." He added being able to offer CO2-free plastics and chemicals gave his company a competitive edge if consumers and society at large are prepared to pay a premium.

The chemical industry aims to become climate-neutral by replacing fossil fuels with renewable electricity as an energy source for production, and also by using it to make climate-neutral raw materials.

The carmakers' search for clean car components is also beginning to be felt in the steel industry, one of the largest emitters. The automotive industry is widely seen as the most important initial client for emission-free steel because the extra cost would only increase a car's price by a small fraction.

British-Dutch Tata Steel Europe has said it plans to start to make green steel by 2027, and produce enough to make 1.3 million cars per year. German rival Salzgitter, an industry frontrunner in using green hydrogen for production, also says demand from the car industry will be key to finance the shift to climate-neutral production.

Premium carmaker BMW has gone further still. The Munich-based company invested earlier this year in an innovative method for CO2-free steel production, billed as part of its aim to significantly reduce CO2 emissions across the supplier network.

"We systematically identify the raw materials and components in our supplier network with the highest CO2 emissions from production. Steel is one of them," said BMW management board member Andreas Wendt.