Court ruling forces govt to rethink climate policy to stay within CO2 budget – law professor

Prof. Dr. Dr. Felix Ekardt, is a lawyer, philosopher and sociologist who is the founder and director of the Sustainability and Climate Policy Research Centre in Leipzig and Berlin. He is also professor of Public Law and Philosophy of Law at the University of Rostock. He represented the 2018 constitutional complaint by an alliance of Solar Energy Support Association (SFV), Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) and many individual plaintiffs which they filed “because of Germany's completely inadequate climate policy, which violates the fundamental rights to life, health, subsistence and property”, and was among the four cases decided by the Federal Constitutional Court on 29 April 2021.

Clean Energy Wire: Could the ruling affect other pending and future climate change lawsuits, e.g. if climate change victims sue greenhouse gas emitters?

Felix Ekardt: There is not necessarily a connection with other such climate change-related legal cases, because they are about compensation and it is questionable whether one can really assign a single liable party to a single injured party in a global event like climate change. In principle, however, the ruling does of course have an impact on lawsuits concerning individual projects, for example, when it comes to the approval of further opencast lignite mines. The chances of a lignite company getting approval for an open pit mine in Germany have dropped drastically since the ruling.

Which of the complainants’ arguments or concerns did the Federal Constitutional Court NOT follow in this week’s ruling?

The Federal Constitutional Court has made it clear that the legislators must not allow the entire remaining greenhouse gas budget to be used up in the next few years, but has not given a definite date by which zero emissions must be achieved.

What do you think of criticism of the CO2 budget approach you just mentioned, which the court used in its reasoning, as well as of the belief that the next generation will be burdened more than today’s? Some people argue that climate protection will become cheaper and easier.

This has been the position of the U.S. government since the time of President George W. Bush. It is not that simple. Above all, the effects of climate change are enormously expensive in economic terms and have a devastating social distribution effect. It is true, and the Federal Constitutional Court acknowledged this too, that it is not possible to give an exact emissions budget because of the uncertainties in current knowledge on the matter. But such exact knowledge was not necessary for the ruling.

But it was still important that the court chose the budget approach?

The German government has always concealed the fact that German climate protection efforts can never be in line with the German emissions budget, no matter how the budget is calculated. Regardless of this, we did not choose an explicit budget approach in our 2018 lawsuit by the Solar Energy Support Association (SFV), Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) and individual plaintiffs, which got the whole thing rolling. We did not calculate an exact budget. In this respect, we are in line with what the Federal Constitutional Court is doing. There is a rough orientation framework of what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicates as a budget. However, we even pointed out in our complaint that the IPCC’s budget indication is still too large.

Info-Box Greenhouse gas emission budget

The Federal Constitutional Court used the notion that all nations, including Germany can only emit a certain amount of greenhouse gases by 2050 (CO2 budget) if the temperature rise is to be limited. “One generation should not be allowed to consume large parts of the CO2 budget under a comparatively mild reduction burden, if at the same time a radical reduction burden is left to future generations,” the court said.

The judges quote the carbon budget calculated by the scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). According to the Special Report (table 2.2) the atmosphere can absorb, calculated from end-2017, no more than 420 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 if we are to stay below the 1.5°C global warming threshold.

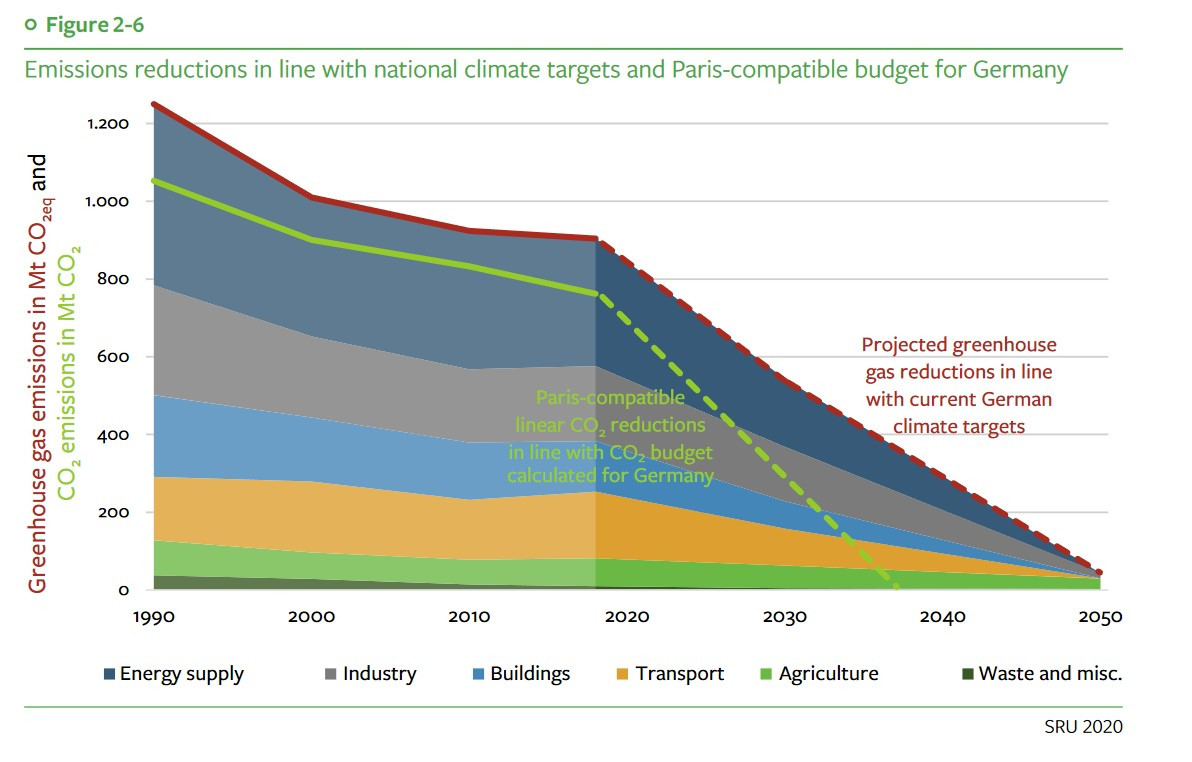

The constitutional court also refers to Germany’s national CO2 budget which has been calculated by the German Advisory Council on the Environment (SRU), a panel of university professors whose mandate it is to independently advise the German federal government on environmental policy issues. Under the assumptions of the SRU, Germany has a Paris-compatible residual budget of 6.7 Gt CO2 from 2020 to 2050 (when it wants to have become greenhouse gas neutral). If the emissions level remains constant (2019 level), the German CO2 budget as calculated would be used up in 2029; assuming linear reductions, in 2038, the SRU said in 2020.

The constitutional court said: “Due to the uncertainties and assumptions involved in the approach [of a CO2 budget], the calculated size of the budget cannot, at this point, serve as an exact numerical benchmark for constitutional review. Some decision-making leeway is retained by the legislator. However, the legislator is not entirely free when it comes to using this leeway. If there is scientific uncertainty regarding causal relationships of environmental relevance, Art. 20a GG imposes a special duty of care on the legislator. This entails an obligation to even take account of mere indications pointing to the possibility of serious or irreversible impairments, as long as these indications are sufficiently reliable.”

The use of the CO2 budget idea has been criticised due to its uncertainties and assumptions. The SRU budget calculations have been attacked for not differentiating precisely enough between CO2 neutrality and greenhouse gas neutrality.

The German environment ministry has so far not adopted the budget approach of the SRU but sticks to emission reduction targets relative to a reference year (mostly 1990) and the overall target of climate (greenhouse gas) neutrality by 2050 which it derives from its obligations under the Paris Agreement.

What specific changes does the government now need to make to the Climate Action Law?

Formally, the government must define the emission reduction targets for the period after 2030 more precisely. In fact, however, it will have to scrutinise the entire present climate policy and not just the Climate Action Law because otherwise our entire budget will be used up in the next few years.

And what measures must be at the top of the agenda for the next government?

The key challenge is to finally stop acting from a purely German perspective. Germany must throw its full weight into the balance at the EU level and not put the brakes on the bloc’s climate policy as it has done in the past. We don't need a better German CO2 price, but rather at the EU level, where Germany must push the EU Commission under President Ursula von der Leyen. We need zero emissions by 2035 or earlier, zero fossil fuels by then in all sectors, including agriculture and cement. This will be the crucial question for the new German government, whether it wants to play the right role at the European level.

What does the ruling mean in international comparison? Are similar decisions to be expected in other countries?

The ruling has no direct impact on other countries, but it will certainly be received with interest because of the reputation of the Federal Constitutional Court and because it is the most far-reaching ruling in the world to date.

And there can definitely be similar rulings abroad. Just as the Federal Constitutional Court ruling was partly based on a comparable Dutch ruling. However, the German ruling is more far-reaching. The whole legal approach – and these rulings – are in line with the fact that the EU is already ratcheting up its climate policy of its own accord, independent of fundamental rights lawsuits. And the German task would be, as I said, not to put the brakes on, but to demand even more ambition.

Are there proceedings similar to the one just decided by the German constitutional court before European courts, such as the European Court of Justice or the European Court of Human Rights?

The Court of Justice of the European Union recently rejected a similar complaint. The European Court of Human Rights, on the other hand, has relevant lawsuits pending. And it may also be that the complainants in our first climate lawsuit, just decided by the German constitutional court, will continue on to the European Court of Human Rights. Because, although we think the ruling is great, it doesn't actually go far enough for us in terms of climate protection.

What additional decision would you like to see from the European Court of Human Rights?

A clearer definition of when zero emissions must be achieved.