Vote in German carmaker state foreshadows national election amid pandemic uncertainty

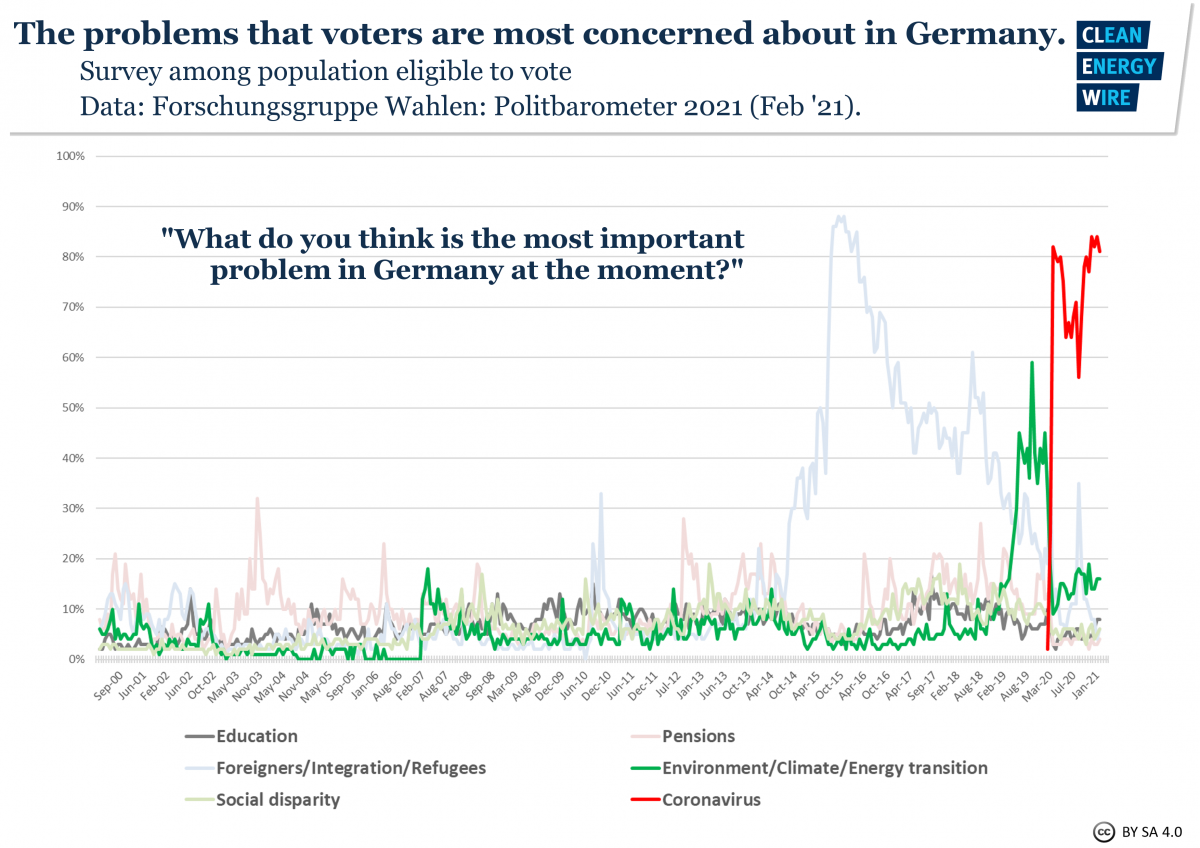

Almost exactly six months ahead of Germany's federal elections in September, a regional election at the other end of the country could have a decisive impact on the course of national campaigns and turn into an early indicator how voters evaluate the parties' concepts to balance climate action with economic prosperity. The vote in the south-western state of Baden-Württemberg on 14 March foreshadows a contest between the conservative Christian Democrats (CDU) and the Green Party that is widely expected to also dominate the general elections half a year later. Together with a parallel ballot in the smaller neighbouring state of Rhineland-Palatinate, it kicks off what has been dubbed a "super election year" for Germany that will see votes in six out of its 16 federal states and, despite the looming omnipresence of the coronavirus pandemic, is dominated by climate action as a key concern for voters and who they will support in September.

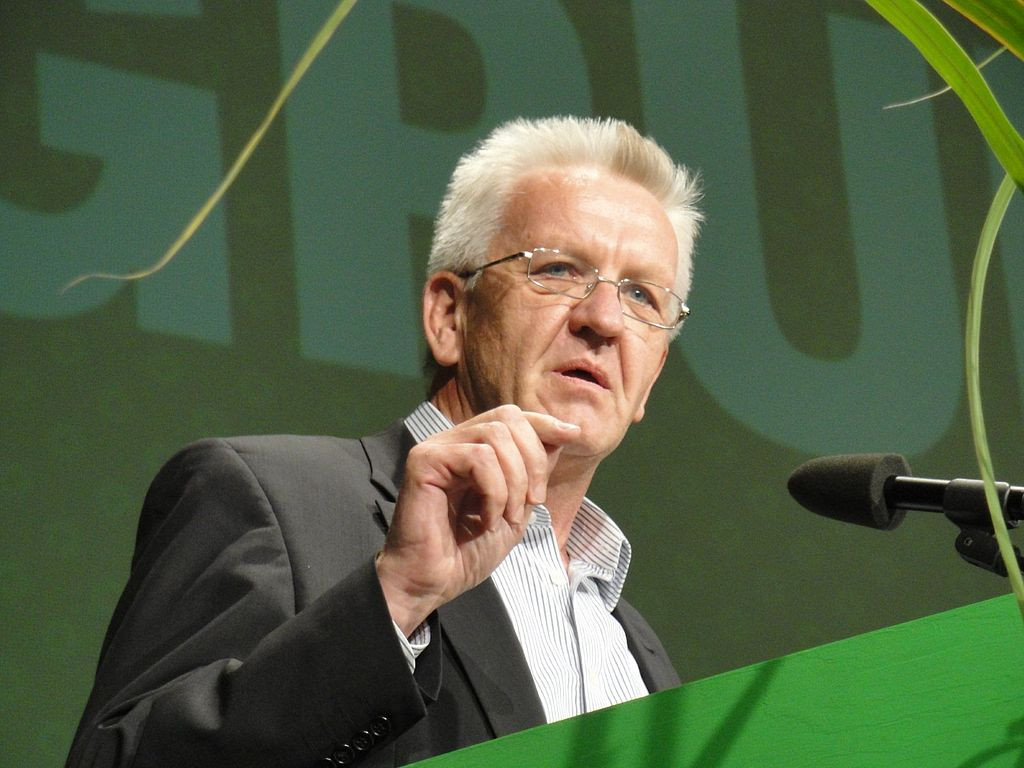

A fundamental difference between Baden-Württemberg and the national elections, however, is that the Greens already lead the government in the economic powerhouse state that is home to many of the country's most successful companies, especially in the automotive industry. In 2011, Green state premier Winfried Kretschmann ended the reign of the CDU that lasted uninterrupted for nearly 60 years in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan, which had happened just two weeks earlier. After winning another state election in 2016, the 72-year-old Kretschmann remains the only Green politician who climbed to the highest office in a state, which many attribute to his ability to also pander to the conservative parts of the electorate despite hailing from a progressive environmentalist party.

At the national level, on the other hand, the Green Party can only hope they will be able to seize the momentum of steadily growing concerns in Germany about global warming and snatch the Chancellery away from the CDU. As the conservatives' unwaveringly popular Chancellor Angela Merkel has decided to step down after nearly 16 years at the helm of the EU's most populous and economically powerful country, the odds for that to happen appear greater than at any other time during the party's history.

The vote for the highest office in Baden-Württemberg thus takes place under reverse circumstances compared to the national contest, with the CDU hoping to eject the Greens from the government in the state capital Stuttgart. But its core issues regarding climate and energy reveal a lot of what also defines national debates and the state's election result might even decide who will ultimately take over the federal government in Berlin. "If Kretschmann wins a third term, this is a mandate for more climate action. It will set the tone for the federal campaign," political analyst Arne Jungjohann from Stuttgart told Clean Energy Wire. In Baden-Württemberg, Kretschmann currently presides over a so-called green-black coalition, derived from the parties’ respective colours, with the CDU as a junior partner. His main rival is Susanne Eisenmann, who serves as education minister for the conservatives in Kretschmann's cabinet.

Conservatives' candidate pick for Chancellor may hinge on Green success

While the CDU briefly managed to overtake the Greens in state polls during the summer of 2020, at a time when the Merkel government's perceived strength in managing the coronavirus pandemic catapulted the conservatives nationwide, Eisenmann's fate has since turned, pulling her party well behind the Greens again in surveys. As of February, the Greens had led the field comfortably, polling at 34 percent, whereas the CDU trailed them as second strongest party at 27 percent. "All signs point toward the re-election," analyst Jungjohann, who is a Green Party member, said. The Greens might even increase their edge, choose to terminate the current coalition and seek a partnership with the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD) or possibly also a tripartite coalition that ropes in the pro-business FDP. These poll at 11 and 9 percent, respectively, meaning the arithmetic could allow a change of government – and might also sketch a possible model for how the conservatives could be removed at the federal level after Merkel has left the stage.

But the result in Baden-Württemberg could also have a decisive impact on the conservative camp's inner workings. Since Armin Laschet, premier of the coal-mining state of North Rhine-Westphalia, won an internal CDU party leadership contest in January, the centrist politician has been tipped as the conservatives' most likely candidate for chancellor. But a clear victory of the Greens in the south-west might help tip the balance in favour of Bavaria's state premier Markus Söder, who leads the CDU's smaller Bavarian sister party CSU and has consistently polled much stronger nationwide as the conservatives' most popular politician after Merkel. The CDU/CSU alliance will decide on their candidate after the two state elections in March.

Söder's chances are also strengthened by his performance in the coronavirus crisis, during which his cautious and restrictive management in Bavaria has generally been received much better than Laschet's more laisser-faire approach in North Rhine-Westphalia. Generally, however, the conservative's performance during the pandemic has come to be seen more and more critically. While voters initially praised the CDU/CSU's response, a series of mishaps spanning a botched vaccination strategy and wavering on school closures has worsened the conservative's image. And the conservatives' worries signifcantly deepened just one week ahead of the vote, as it was revealed that at least two MPs from both the CDU and CSU had used their political influence to enrich themselves with mask procurement deals in spring 2020.

Both politicians, with one hailing from Baden-Wurttemberg and the other one from Bavaria, were swiftly removed from their parliamentary groups as they faced immense pressure from an outraged party leadership to step down altogether, but the damage to the CDU's prospects at the state elections had arguably already been done. While this could lead fewer votes for the conservatives, as potential voters abstain from voting or cast their vote for the Greens, the FDP or the SPD, some observers are fearing that this could ultimately also benefit the far-right populist part AfD, who has rejected most coronavirus response policies since the early days of the pandemic.

A coalition with the Greens is seen as the most likely option for the conservatives to remain in power at the national level and is also a favourite with voters. A candidate who credibly supports such a partnership could therefore be seen the wiser choice by many in the conservative camp too. And whereas Laschet has only recently stated that between his party and the Greens "there is no common project, no common idea that we stand for," Söder has repeatedly courted them, arguing that "many people in the country feel it is the right option." If the Greens again achieve a clear victory in Baden-Württemberg and the CDU performs poorly there and also in Rhineland-Palatinate -- which is seen as one of the remaining strongholds of the SPD thanks to its popular state premier Malu Dreyer -- doubts about Laschet’s appeal may arise handing his Bavarian competitor an advantage with conservatives.

Saving combustion engine no longer priority for Baden-Wurttemberg's party leaders

Back in Baden-Württemberg, the two top candidates -- Eisenmann and Kretschmann – demonstrated in a TV debate ahead of the election that both parties have little wiggle room to deviate from a general trend towards embracing a scale-up of cleaner technologies. For the home state of icons of the combustion engine age like Daimler, Porsche or Bosch, the shift to electric mobility possibly poses a greater danger than to any other German region. Some fear that the prosperous Stuttgart region may face structural economic decline if the major players adapt too late to the technological shifts that reshuffle the playing field globally.

In the debate, both candidates were bound by duty to highlight the carmakers’ key position in Baden-Württemberg. While Kretschmann praised them as "one of the backbones of our economy," Eisenmann said she wanted "the best cars to be developed and produced here still tomorrow and the day after that." But none of the two questioned that great disruption lies ahead and electric mobility will be the new game in town. And although the CDU candidate threw combustion engines a lifeline by saying that "hydrogen, battery, synthetic fuels or even biogas" could also offer environmentally-friendly ways to move a car, none of them outrightly insisted any longer that diesel or petrol-driven cars have a bright future ahead of them. For Kretschmann, this marked a clear shift from earlier times.

As the most successful Green politician in the country in the past ten years, Kretschmann has gained a reputation as a state premier with an appeal far beyond the Greens' base but which was partly built on concessions in the form of industry-friendly or at least supportive policies, not least in the car sector. Some have considered this the recipe for a long-lasting grip on the levers of power of his party, which carefully developed its relationship with business over the past years and unlocked support potential among centrist voters. But for some climate activists, the strategy has been equated with the Greens abandoning their environmentalist identity in favour of securing their hold on power. This has led to the launch of the "Klimaliste" (Climate List), a collection of voter groups that run on a staunchly pro-climate platform and could scoop up important votes from the Greens. "The Greens in Baden-Württemberg have lost a lot of credibility. They are not a Green party anymore. They are just the CDU with some green paint on them, in my opinion," Alexander Grevel, one of the list's founders, told Clean Energy Wire.

While the Klimaliste is unlikely to gain the five percent of votes necessary for the party to make it into the regional parliament, it puts pressure on the Greens and may cost precious votes in the race for the top spot. The 32-year-old Grevel said the Klimaliste in the state currently counts some 440 members, with about two-thirds with a background in climate protest groups like Fridays for Future or Extinction Rebellion. For example, they take issue with the fact that Baden-Württemberg has a relatively poor renewable power expansion record despite having been run by the Greens for ten years. While Kretschmann has dismissed criticism from the Climate List as "impatience of the youth," for Grevel and his fellow activists the Green Party's success means they have become "part of the establishment they wanted to fight in the beginning."