Start-up Next Kraftwerke's renewable virtual power plant stabilises grid

Company profile

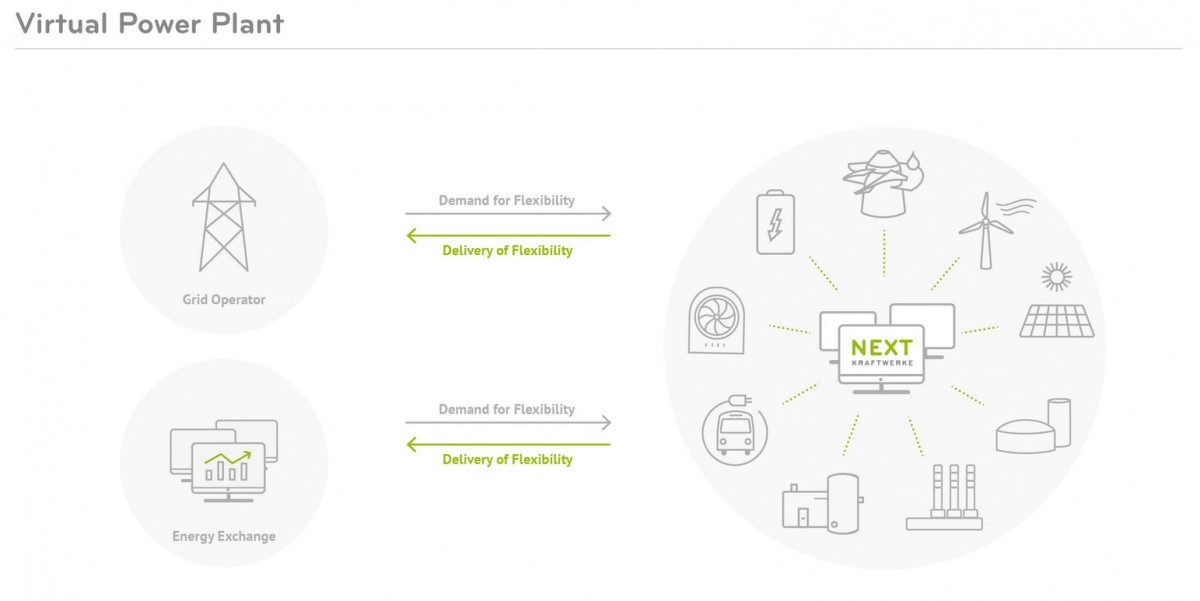

- Next Kraftwerke calls itself a “digital utility” and “a power plant operator without any power plants.” It has digitally bundled more than 7,500 renewable power units with a capacity totalling almost 7,000 megawatts into one of Europe’s largest virtual power plants (VPP) that balances renewable power sources with commercial and industrial consumers in Germany and neighbouring countries. The company is also a power trader.

- Cologne-based Next Kraftwerke was founded in 2009 and currently employs around 150 staff. It registered sales of 383 million euros in 2017, the lion share in power trading.

- Dutch renewable utility Eneco, which might be taken over by oil major Shell, bought a 34 percent stake in Next Kraftwerke in 2017.

Why Next Kraftwerke matters

- The company’s virtual power plant showcases how an electricity system can be operated with a large share of renewables, thereby saving sizeable amounts of CO2 – it replaces the equivalent of two large coal-fired power stations, and also provides ancillary services to the power grid.

- Next Kraftwerke also illustrates the potential of digitalisation in the shift to a renewable electricity system.

Find CLEW coverage of Next Kraftwerke here.

What Next Kraftwerke says

Clean Energy Wire spoke to the company’s co-founder and CEO Hendrik Sämisch.

Clean Energy Wire: How would you evaluate the current progress of Germany’s energy transition?

Sämisch: I think we need to consider different levels separately – on the one hand, there’s technology and economics, and on the other, there is policy. As far as policy is concerned, there is not much movement in Germany now. There are a lot of discussions on reforming support programmes and about grid extensions, but we are still operating in a market design that does not do justice to the demands of a world powered by renewable energy. There is little dynamism and we must acknowledge that other countries are moving forward more decisively and address the problems more constructively. You get the impression that development has ground to a halt in Germany. That’s bad news for this country as a business location.

In contrast, the technical and economic development of renewables is racing ahead, leaving policy in the dust. We have reached a turning point: large renewable installations are no longer built to save the planet, but because it has become so cheap to build them. We have reached that point in many countries, and we are about to reach it in many others. That is crucial. Increasingly, policy’s role is no longer to trigger deployment, but rather to react to what’s happening in the markets.

Even in Germany, some technologies have reached that point. The first large-scale PV and wind arrays are being built without support payments.

What regulatory change would advance the energy transition the most?

Obviously, a comprehensive solution would be to introduce a fair carbon price. But I suppose that’s not really a concrete policy demand because it’s such a huge subject. Also, we’re active on the market on a much more operational level, therefore I would choose another subject. One issue we’re very critical of – and which is often overlooked – is that grid bottlenecks cause immense costs. That’s because Germany clings to the illusion of a unified pricing area. But, in effect, we’re transferring hundreds of millions of euros from west to east and from north to south in order to keep electricity prices the same. We must find a way to deal with the common situation of strong renewables production in one part of the country and strong power demand in another. Investing a lot of money in switching power plants on and off can’t be the right answer to this problem. We need an integrated European power market, which will also include grid extensions. Temporary regional price differences shouldn’t be a problem. This is a central issue with a lot of market design details attached to it. If you could draw up a power market with a high share of renewables on a blank sheet of paper, it would look very different from what we have today: flexibility would have a price, for example. The market should also see early on that very cheap renewable power is available in many hours of the year, but also that there are shortages at other times. The market needs signals for both so it can incentivise investment - for example in a gas power plant that can become profitable by generating power only for a few hundred hours per year, when electricity is scarce and therefore very expensive.

The technical and economic development of renewables is racing ahead, leaving policy in the dust

Do you believe Germany is still a pioneer in the energy transition?

Germany did manage to make a great leap in the period between 1998 and 2005, when it placed a very large and also risky bet on renewables to bring the costs down, which worked surprisingly well. However, the country didn’t make the second or third step with the same consistency. But at least the energy transition’s burden on households is about to decrease in the years to come. It will be a rewarding task to be minister for economic affairs – we will witness a further expansion of renewable capacity while the renewable levy will fall year after year.

There is still great interest from abroad in finding out what we did in Germany, what went well here, and what didn’t. The experiences the country has gained during its head start are still valuable. But other countries are catching up fast. I’m not an expert, but there is a lot of movement in many countries – just look at China. It’s incredible how they’ve managed to lower costs in PV solar – just imagine what would happen if they do the same for batteries.

We see a rapid renewable energy rollout in lots of other countries where this has become profitable. In many markets, it has become even more obvious that policy can no longer stop the breakthrough of renewables – just think of the US, where federal policy is not exactly climate-friendly at present. Despite this trend on a global scale, the large technology companies are not very active in this field yet. So, there are still lots of opportunities for us.

What do you consider the most important milestones for your company in the future?

We have already expanded our market in Europe – we offer market access for renewables as well as power generation forecasts, and experience a rising demand for solutions to control renewables in order to balance the grid, and to understand what will happen in the power market in the hours to come. The increasing rollout of renewables poses many questions for grid operators in countless countries that need answering: Where does the power come from? Where does it go? What will happen in four hours? – and we’re happy to assist them by saying: ‘We can tell you how much power renewables generate this very second at each grid intersection, we can visualise the process, and we can forecast what will happen in four hours.’ These issues will become increasingly important in every country on earth within the next five years and we want to provide answers by using our technology.

Who do you consider your most important competitors?

That’s difficult to answer because we’re active in several segments of the market. But I can approach it from another direction: the conventional energy industry has not become a real competitor. What we do is not relevant to them – from their point of view, we’re about technology, and about meteorology. That’s why we’re keeping an eye on interesting technological developments. This is still a rather abstract competition, but we will have to face it. We need machine learning and algorithms to improve our weather forecasts, for example. We need to be on the lookout for good ideas. Just from reading the newspapers, I would guess that it wouldn’t take very long for Google Alpha to understand how to deal with huge amounts of weather data, which means competitors could appear in the longer run. But at present, on a more operational level, our competitors are mainly power traders, power companies and technology firms that work in energy – such as Siemens or ABB.

You are already expanding in various European countries. Do you have any plans to enter markets beyond Europe?

Yes, we already have a number of Virtual Power Plant (VPP)-as-a-service projects outside of Europe, where we build up a VPP infrastructure for utilities or other aggregators. We have accumulated quite a bit of experience and technology by operating in Germany, which is a real bonus because this was the first country with a large number of renewable energy installations. This experience gives us an advantage that we would like to carry into the world. Publicly, we have mentioned projects in Japan and South Korea, but we could basically go anywhere. Japan is very interesting because that country has just launched an energy transition policy and is very keen on technological partnerships – there is a very positive atmosphere at the moment. But we also see many opportunities in other Asian countries, as well as in Africa, and North and South America. This also poses major organisational challenges for us, and we’re trying out a lot of new things. From a commercial perspective, these opportunities look very promising.

Do you find it worrying that oil majors appear to look upon your area of expertise as a business opportunity and have started to expand rapidly by swallowing smaller companies? Shell has bought solar battery pioneer Sonnen and might also become owner of green power provider Lichtblick by purchasing Dutch utility Eneco, which is also one of your shareholders.

First, one must ask: Why does Shell do this? I guess various motivations are possible: marketing and greenwashing, or even an attempt to stifle competition. But, to be honest, I don’t think that’s the case here. A major group like Shell doesn’t need to bother. Therefore, I believe the decisive factor is the realisation that it won’t be able to make money with oil and gas in the medium term. Given the incredible profits they make in this business today, why not pour money into the sector that will one day replace it, and is still comparatively cheap? There is probably a sober economic consideration behind these moves, and Shell now appears to march down that path very decisively. It’s true that we had this sort of movement once before – just think of BP’s slogan ‘beyond petroleum’ – but I think this time they are serious about it.

Still, this poses some important questions: will we fill in the old trenches and join forces to find the best solutions? It’s also a fact that these developments change the environment for other emerging renewable companies. I doubt that Shell’s company culture has already evolved as much as their management decisions. The conventional oil and gas world simply works totally differently from the renewable world. I don’t want to play them off against each other, but I’m convinced that a business model based on producing CO2 is not the right one and should disappear sooner rather than later. But to reach that point, why should it not be an option for large emitters to support those with cleaner solutions by investing in them? We will have to see. At present, I’m quite happy to work with a Dutch green energy provider as a minority shareholder. You just notice there is a common spirit – it’s about working with people who want to make the energy transition happen.

But anyway, you can also see it in a positive light: a company that makes billions of euros by producing CO2 uses some of its profits to change its business model. That’s good news for the world. And it’s not only Shell – Total is doing the same. They’re all doing it, except the US oil majors.

What do you consider the most important developments awaiting your sector? Do you expect large-scale storage to have a big impact, for example?

We need storage, and the issue suddenly becomes very pressing with the arrival of electric mobility. That’s one of the key issues at present, and again, we have many sceptics out there who say that it can’t work because of regional grid bottlenecks and so on. Yes, these issues need to be solved, but I’m confident we will manage. It will be exciting, but I’m not afraid that we will run into serious technical problems. There are thousands of new business models out there.

Does electric mobility impact your business directly?

It depends, and I can’t wait to see what will happen in the years to come. Soon, we will reach the point where electric cars can compete with diesel models on price and range – perhaps in five years. One thing is certain: I will definitely not buy any more internal combustion engine cars! And everybody else will soon think the same. For Next Kraftwerke, this means that we will have one more source of flexibility to deal with. Millions of cars will be plugged in overnight and need to be charged, say, 80 percent by the morning. That gives you a lot of storage to play around with. Will this be an option for us? This would imply that we’re entering households directly. Do we want that? Or do we want to find partners that are better at it, and offer services to them in the background? These are strategic questions we must deal with.

But, in this respect, there is a locational disadvantage in Germany, because we don’t really have a large number of electric cars yet. In contrast, there are already a lot of business models in Norway and the Netherlands. We’ve already started a project in the Netherlands in order to understand the possibilities of electric cars with our partner Jedlix, where we offer balancing power. But the situation will radically change in Germany soon. We will also be on the lookout for new alliances – carmakers could enter the power sector, for example.

How would you rate Germany as a startup location?

The country worked pretty well for us. But it’s true that financing remains a constraint compared to some other markets. In general, I never felt that bureaucracy was a problem while launching and nurturing a startup. Also, Germany’s political system is stable, and the infrastructure is good – you can get anywhere you want, and our internet connection is reliable – what else do you need?