Shake-up in Bavaria's election may impact German energy policy

Voters in Bavaria seem poised to deliver a political earthquake at the upcoming state elections that could impact politics in Germany’s capital Berlin as the long-ruling regional conservative CSU faces a historic slump. The latest polls even suggest the possibility of a coalition government with the Green Party in Munich after the vote on 14 October. But whether a coalition in Bavaria will help end the standstill in energy and climate policy of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government is far from certain.

The Christian Social Union (CSU) has ruled Bavaria for more than 60 years and is part of the federal government, together with Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Social Democrats. The usually self-confident party has seen its poll ratings slump over the course of the campaign as the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) on the right and the Green Party on the center-left have been eating into its voter base.

The traditional CSU is still expected to clinch by far the largest voter share in one of Germany’s richest and most populous states and will therefore continue to lead the government. However, the party’s attempts to fend off the right-wing populists have fuelled an internal brawl in the federal government's conservative camp over immigration and paralysed national politics, putting other vital issues – like climate and energy policy – on the back burner.

The disputes over immigration and a host of other topics plague Merkel’s government – which just took power in spring 2018 after six months of coalition talks - and have even threatened its collapse. In an unusual alliance, traditional energy companies, the renewables industry and environmental organisations have lambasted the grand coalition for its avoidance of energy policy issues that are core to both the country’s energy transition and its economy.

Political scientist Gero Neugebauer warns that the Bavarian election may not fix the problem. “The fundamental disputes will not be resolved with the election,” he told the Clean Energy Wire. “All actors have internal problems, the solutions presented so far – for example in the areas of housing, climate policy and diesel emissions, or immigration – are fragile, and doubts about the coalition's ability to govern remain high.”

Conservatives set to lose absolute majority in Bavaria

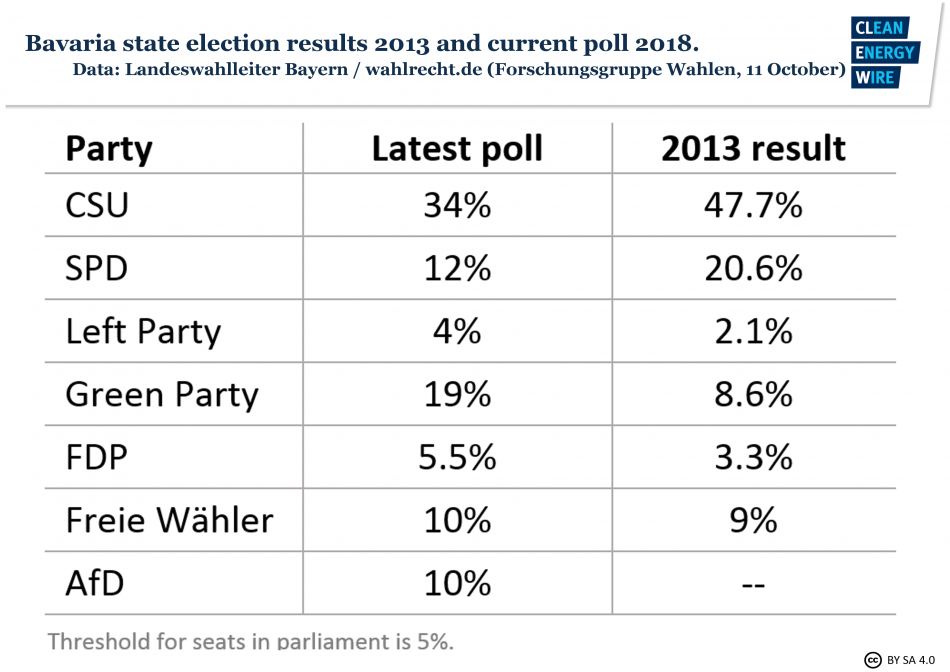

Ten days before the 2018 election, polls point to the CSU losing the absolute majority it gained in 2013, securing only about 33-35 percent of the vote – a devastating prediction for a party whose share is usually more than 50 percent and hasn’t fallen below 43 percent in more than 60 years. A re-shuffle of leadership positions in the party and the national cabinet could thus be in the offing.

According to the polls, the Green Party (19 percent) and the far-right populist AfD (10 percent) would gain the most over previous results. [Find more information in the CLEW factsheet Facts on the German state elections in Bavaria]

In tradition-bound Bavaria, polls show that immigration dominates the topics most important for the electorate, followed by cost of living/rent and education. Environment and climate change on the other hand hardly play a role, despite the fact that they are closely linked to national policies that are vital for some of the key industries in the economic heavyweight state. Only about ten percent of voters label these as some of the most important problems Bavaria faces.

The picture-book state with its rich green alpine landscapes, Walt Disney-inspiring Neuschwanstein Castle, Oktoberfest and champion football club FC Bayern Munich, is one of Germany’s most vibrant innovation hubs. It is home to corporate giants like BMW, which has embraced e-mobility more vigorously than other German carmakers, and to industry behemoth Siemens, but also to start-ups and smaller players like decentralised energy system company Sonnen.

In recent years, policies related to the national energy transition, the Energiewende, have topped the headlines in Bavaria – from shutting down nuclear power plants to building massive new power lines that carry electricity from wind farms in the north to industry in the south.

“Number one green energy state”

On energy and climate, CSU representatives have fought for favourable conditions for Bavarians who commute to work by car, for companies that manufacture these cars, for farmers who want recurring compensation payments for building power transmission lines on their land, for citizens who want the power lines underground, for people with rooftop solar PV panels, and for those who oppose wind turbines too close to their homes. The CSU not only rigorously defends the interests of its conservative – and often rural – Bavarian electorate, it also does so on the federal level. [Also read CLEW’s factsheet for background on the influence of federal states on Germany’s energy transition]

In a recent TV debate by public broadcaster Bayrischer Rundfunk, state premier and CSU frontrunner Markus Söder called Bavaria the “number one green energy state”.

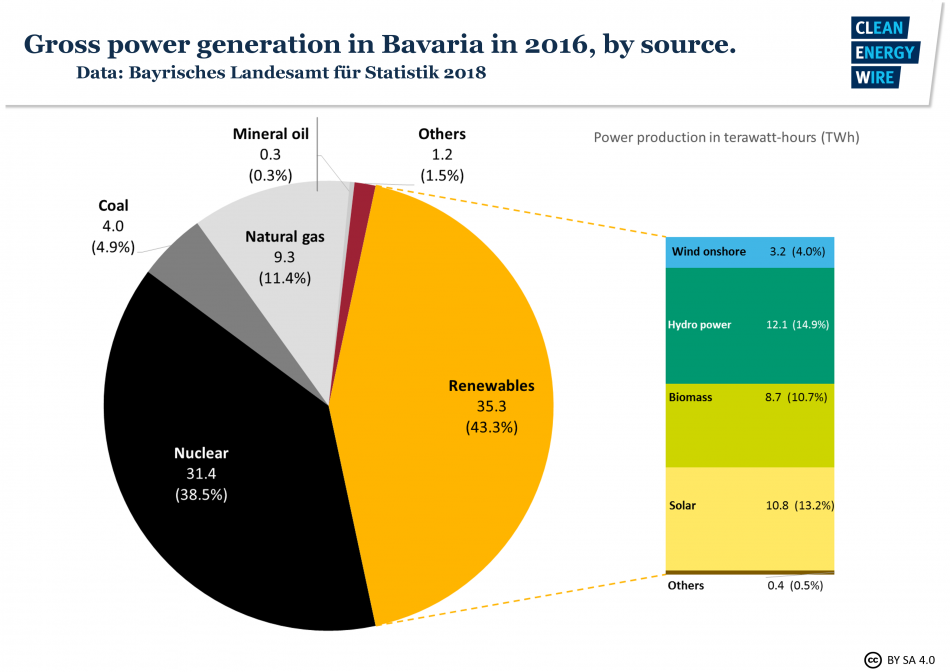

While Bavaria produces very little electricity from coal, it generates a lot of bioenergy and has the highest amount of installed capacity of solar PV, geothermal and hydro power of all federal states. In 2016, 43.3 percent of power generation came from renewables, most of it from hydro, PV and bioenergy.

The state government’s 2015 “Bavarian Energy Programme; secure – affordable – environmentally-friendly” stipulates several energy transition targets for 2025. Primary energy consumption is to be reduced by 10 percent over 2010, and renewable energy should cover 20 percent of primary energy consumption and 70 percent of power generation.

So far, however, Bavaria lacks a sizable number of wind parks to help reach these goals. New installations of onshore turbines have decreased since 2014, which has led to stark criticism by the regional branch of the German Wind Energy Association (BWE).

“Sorry, Bavaria just isn’t a wind power state,” said Söder in the TV debate, and criticised the aesthetic impact of 150-200 metre-high turbines – giant “asparagus” – on the state’s landscape. Wind power opposition in Bavaria resulted in the so-called 10H-rule, which the government introduced in 2014. It stipulates that new installations must maintain a distance from the nearest settlement equalling ten times the turbine’s height.

Bavaria also still produces almost 40 percent of its electricity from nuclear energy. According to the Renewable Energies Agency (AEE), it is “relatively clear that Bavaria will not be able to cover its own power needs after nuclear power plants are switched off [at the end of 2021 and 2022], and will increasingly depend on imports.”

As major German power lines from the windy north down to Bavaria will likely not be finished before 2025, securing power supply in 2022-25 will be a challenge for the next Bavarian government, writes AEE.

“Laptop and lederhosen”

Bavaria likes to portray itself as a modern state rooted in tradition, often summed up in the motto “laptop and lederhosen”. The most recent example is “Bavaria One”, the CSU government’s plans for the state’s own space programme. Premier Söder was mocked on social media for the self-referential ambitious new plan, because his portrait was used as its logo.

Zukunft heißt Technologie. Bayern ist Marktführer: wir investieren in Digitalisierung, Robotik, künstliche Intelligenz, Hyperloop und Raumfahrt und entwickeln sogar Quantencomputer. pic.twitter.com/v3GpSi7YP5

— Markus Söder (@Markus_Soeder) October 2, 2018

The Bavarian innovator Sonnen was recently featured in a New York Times article as a small enterprise that started out supplying batteries, but has the ambition to challenge and even supplant Germany’s giant utilities as “a kind of energy Facebook”.

At the other end of the spectrum, German luxury car giant BMW – headquartered in Munich – is seen as a pioneer in e-mobility and sustainability among German carmakers. And, following in the footsteps of federal states Saarland, Rhineland-Palatinate, North-Rhine Westphalia, and Baden-Württemberg, the Bavarian government recently started to vie for the construction of a Tesla Gigafactory in the state.

After the vote – a possible role for the Greens?

Should the CSU’s lone rule in Bavaria come to an end on 14 October, however, the AfD is not seen as a partner. National and state polls show the Greens on the rise, benefiting from both the surge of the AfD and perceived government chaos.

The prospect of the Greens forming a coalition with the CSU post-election in Bavaria is still quite uncertain, but many in the party are hopeful this could help reshape the state’s energy and climate policy.

Katharina Schulze, one of the two top candidates of the Green Party, has signalled openness: “I didn’t go into politics to die in beauty on the sidelines,” said Schulze recently. The Greens want to “get rid of the wind energy blockade (10H)” and reach 100 percent renewables in power production by 2030.

Looking ahead to after the election, the CSU itself is largely keeping mum on possible coalition scenarios and campaigns for the strongest result possible. Bavarian voters should be wary of the possibility of a “completely unstable government” like in other states, said Söder recently. “I advocate for leaving it the way it is.”

From 2008 – 2013, the Free Democratic Party (FDP)’s were in coalition with the CSU, but this time they are seen taking about 40 percent of the vote together, according to current polls. The FDP is also at risk of not passing the 5-percent threshold to enter parliament, while the Left Party has the chance to make it into the parliament for the first time. The conservative Free Voters’ party head Hubert Aiwanger has signalled his party would be available for a coalition with the CSU. The Free Voters are currently polling at 11 percent.

According to current polls, the only two-party alliance could be forged with the Green Party. Forschungsgruppe Wahlen recently found that 50 percent of voters said a coalition of CSU and Green Party would be “good”, while only 31 percent said this of the CSU governing alone.