Rail cargo emissions in Germany

The experts say:

“Trains are already largely, and could be fully, electrified – maybe by replacing diesel with hydrogen.” - Greg Archer, director clean vehicles, Transport & Environment

To meet the Paris Accord goals, nearly all global aviation activity at short to medium distances (up to 1,000 km) must be replaced with high-speed rail by 2060, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in 2017.

“In the immediate future, rail freight operators should concentrate on intermodal shipments. Because, while overall volumes may have declined, intermodal rail freight has seen significant growth over the last few years.” - Libor Lochman, executive director of Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies (CER)

"I have the impression that [Deutsche Bahn] has a management problem when it comes to freight transport. Management has changed a lot in the last few years and bad relationships with employees have been developing there for years. That’s why the willingness of the workforce to modernise operations is very low.” - Christian Böttger, Berlin University of Applied Sciences

The problem:

Rail freight transport is one of the most sustainable ways of moving cargo around – but the share of rail in the German market’s freight transport sector is stagnant at best, while its operators are chalking up losses. By contrast, the use of less climate-friendly modes of transportation like trucks and airplanes are on the rise.

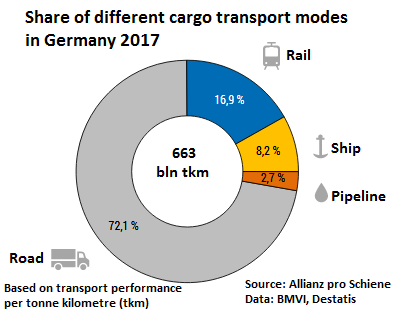

After a spike in growth figures at the beginning of the century, rail’s share of global freight transport has been stuck below 20 percent. In Germany, the figure stood at just under 17 percent in 2017, about the same as ten years earlier, and much below that registered in neighbouring countries Austria and Switzerland, where rail cargo boasts a share of 30 percent and 42 percent, respectively. By contrast, trucks moved nearly three quarters of all commodities in Germany, according to data compiled by the transport ministry (BMVI). In the EU, rail freight as a whole has declined since 2006, with one of the most negative developments happening in Germany.

Railways are the linchpin in intermodality, the connection of different modes of transport for the passage of one piece of cargo, which can increase efficiency and sink emissions. According to Germany’s Federal Environment Agency (UBA), in freight transportation emissions per tonne kilometre (tkm) are about three quarters lower for trains than for trucks in Germany.

Greenhouse gas emissions in rail transport occur either directly through locomotives running on fossil fuels like diesel - a rather small portion of total traffic volumes - or through the emissions that correspond with Germany’s current power mix for electrically-driven trains. Given the terms of the Paris Climate Agreement, these should be close to zero by the middle of this century.

Source: DB Cargo AG.

Railway operators pay taxes on fuel and revenue that most international air and sea transporters don’t pay, giving the latter an unfair advantage. In 2017, state-owned railway service Deutsche Bahn bought 27.5 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity, which equals about five percent of Germany’s total consumption. Despite its high electricity use, the company does not enjoy rebates from Germany’s renewables levy, while the diesel most trucks run on is still taxed lower than other fuels.

A further problem is that railways in Europe are surprisingly heterogeneous when it comes to infrastructure, interoperability, laws, and also language –factors that could all be overcome with sufficient political will.

The railway services themselves, however, bear blame too. Uneven service, bad management, and slowness in going digital are just a few of the factors that weigh on the dynamic development of a sector which, throughout its over 180 years of existence in Germany, has traditionally been heavily controlled by the state.

According to a study conducted by the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research Heidelberg (IFEU), rail freight is not more climate-friendly per se than road haulage. In order to maximise the benefits of trains, they need to be well-connected to the road system for loading containers from and on trucks, have a high utilised capacity ratio, and should be made as long as possible.

The fix:

Like many environmental groups, logistics experts and freight forwarders are convinced that much freight from road, air, and sea needs to be, and will be, shifted to rail and inland shipping. Pro-rail lobby group Allianz pro Schiene says increasing the share of railroad freight is imperative for reaching Germany’s climate goals and for preventing further clogging of the country’s road traffic system. The group says bringing rail’s share to 25 percent of all cargo transport by 2025 is possible if decisive political action is taken.

Advocates of rail freight call for more investment in infrastructure, the abolition of rail taxes, more and better linking of railways, more intermodal connections, a higher share of rail in combined transport, and better service from the railways themselves. Crucially, they call for the harmonisation of European standards, which continue to be a burden on the sector’s breakthrough. The policy priorities of the Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies (CER) for 2014 to 2019 calls for a three-pronged approach to help the railways attract business:

- Harmonise the railway market’s regulation at EU level to encourage investment

- Develop a new intermodal strategy for transport, and pro-actively improve the rail links with port cities and inland waterways

- Draw up a pro-growth agenda for the railway sector, invest above all in high-speed rail, and improve interconnections between single-modal networks and other infrastructure

Rail’s carbon footprint is small and shrinking further as ever more railway companies switch to electricity – and as ever more electricity is renewably generated. Some 90 percent of Germany’s railways are already electric, and since 2018 Deutsche Bahn has heavily publicised its pledge to buy as much green power as it needs to operate its long-distance services. However, this does not mean that the state-owned company’s power mix is “100 percent green.”

Merely 45 percent of Deutsche Bahn’s total power use will be sourced from renewable sources, and this share will not be raised before 2020. The remaining 55 percent come from nuclear, gas, and coal-fired plants, for which the company has long-term supplier contracts, drawing criticism from organisations like the research institute Green Budget Germany (Öko-Institut), which accuses Deutsche Bahn of misleading its customers into believing that all of its trains run on green power all the time. By 2020 the latest, Deutsche Bahn will start using power generated by the new Datteln 4 coal-fired plant.

However, the company has said it plans to halve its specific greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and become entirely carbon-neutral by 2050 – meaning it intends to reduce the emissions per kilometre travelled or transported, not necessarily its total emissions. According to klimareporter.de, Deutsche Bahn head Richard Lutz said that valid total reduction goals are hard to define given the political goal to increase the share of railroad in passenger movement and freight transportation.

Renewable energy sources are scheduled to cover 70 percent of the company’s total power consumption by 2030, and its freight branch, DB Schenker, has pledged to grow without increasing its CO2 emissions in the next decade. Deutsche Bahn has promised to publish regular updates on its carbon footprint to make its climate protection efforts transparent, but a major part of its total freight emissions also stem from transport with trucks, ships, or airplanes, and two-thirds occur outside Germany, making exact emissions accounting difficult.

Germany’s government coalition of the conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD) has promised to push up the share of rail transport in their coalition agreement. Already in 2017, under the previous government, the German transport ministry, together with rail freight companies, announced its “Rail Freight Masterplan,” which outlines concrete measures in different areas to increase the share of rail cargo.

These include the reduction of track access charges, which took effect in July 2018 and are supposed to fall further after years of increases; lower taxes for rail cargo forwarders; the expansion of important rail cargo hubs; facilitating research on new rail power systems; provisions for greater train lengths; the digitalisation of rail traffic management systems; and the hiring and training of additional staff.