Germany's maritime freight emissions

What the experts say:

“Shipping has gone egregiously underregulated for years. We must apply the same standards that we have for automobiles. Ultimately, the technology for going electric isn’t so different.” Daniel Riegler, Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU)

“Diesel fuel will presumably remain the dominant energy source in inland shipping in the long term. Synthetic fuels are therefore indispensable for emission-free inland shipping.” Federation of German Industries (BDI), Climate Paths study

“We’re not going to see real progress in reducing emissions in either air transport or shipping until the tax advantages they have – and which rail doesn’t have – are removed. Currently, the dirtiest fuels are being rewarded.” Michael Cramer, German Green Party politician and Member of the European Parliament

The problem:

About 90 percent of international commodity trade is handled by maritime shipping companies. Consequently, the maritime freight industry of export-champion Germany is big business that boasts globally ranked shipping companies, state-of-the-art ports, and reliable logistics. German shippers owned 6 percent of the global merchant fleet in 2017. The respective figures were 21 percent for container ships, 10 percent for multi-purpose ships, and 3 percent for bulk carriers. Hamburg, Germany's biggest port that is dubbed its "gateway to the world", ranks 17th in the list of the world’s top 50 container ports.

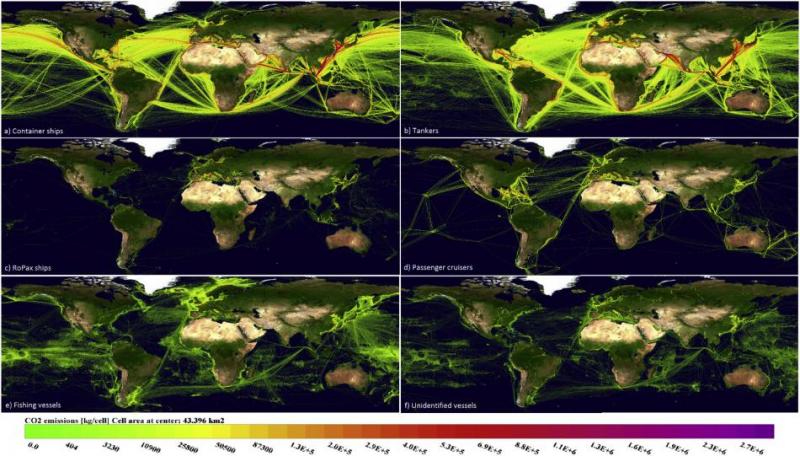

Like that of most other countries, Germnay's merchant fleet mainly runs on CO₂-intensive heavy oil. About three-quarters of global shipping emissions (international, domestic, and fishing combined) are freight-related, according to data provided by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). The remaining CO₂ emissions come from cruise ships, passenger ferries, fishing vessels, service ships, and other non-freight vessels. In the specific area of international shipping, the share of freight-related CO₂ emissions rises to almost 90 percent.

If treated as a country, the global marine transport sector would have ranked 6th in terms of CO2 emissions in 2015, just below Germany, according to the ICCT. In 2012, the year for which the most recent data compiled by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) is available, international shipping was responsible for more than two percent of global emissions.

Ship emissions are expected to increase in absolute terms, and shipping’s share of global CO₂ and GHG emissions is also projected to rise. As international trade soars, so are maritime freight volumes. If the sector remains as unregulated as it is today and if ambition in shipping continues to fall behind efforts in other sectors, international freight and non-freight maritime transport could be responsible for a full 17 percent of total global emissions by 2050, according to a study published by the European Parliament. In addition to its carbon footprint, heavy oil also pollutes the air with extremely high doses of other of potentially harmful substances, such as sulphur oxide and nitrogen oxide (NOx).

Emissions from international water-borne navigation are listed in the emissions inventories sent to the IPCC as memo items, but they are not counted towards a country’s total emissions. Germany listed 8.2 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions in 2016 for international shipping, a little less than 1 percent of its total greenhouse gas emissions reported that year.

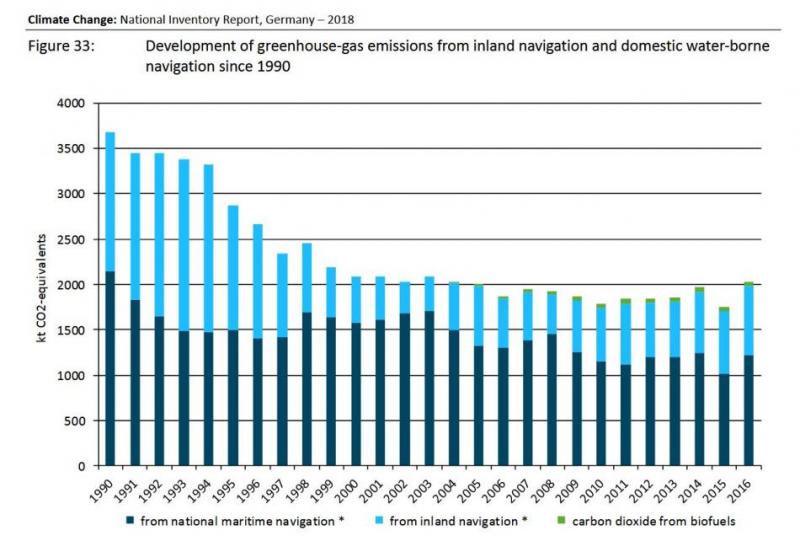

By contrast, emissions from domestic shipping are listed in the national inventories. With a total freight volume of 1.9 million tonnes, domestic water-borne navigation was responsible for 0.22 percent of Germany’s total CO₂ emissions in 2016.

The ICCT argues that shipping fuel consumption and, as a consequence, greenhouse gas emissions are increasing rapidly. The constant increase in vessel size and speed cancells out advances made in efficiency. Of Germany’s 1,500 container ships, over 100 are now classified as “mega-ships,” which are as long as three football fields and can carry the equivalent weight of 15 Eiffel Towers.

German Green Party MEP Michael Cramer argues that “The crux of the problem is that the big ships burn the dirtiest oil of all. In fact, the larger tankers and freighters are just big garbage incineration factories on the seas,” Cramer says, referring to heavy oil, which is a by-product of petroleum distillation.

A 2015 European Parliament report looked the problem straight in the eye. To stay below 2 degrees Celsius, the report said, global emissions of the shipping sector must be 13 percent lower in 2030 than they were in 2005. In 2050, they should be 63 percent lower than in 2005. If the additional non-CO₂ climate change-relevant emissions are taken into consideration, these reduction targets “would need to be even more stringent”, the report concluded.

The fix:

Environmental groups say that an international deal at the United Nations' level is the only way to effectively bring down greenhouse gas emissions and increase energy efficiency in shipping. An important aspect of the problem is the difficulty to assign emissions from international shipping to an individual country, says Bryan Comer, senior researcher at the ICCT. A vessel might be owned by a German shpping company, operated by another based in Denmark, be flagged in Panama, and transport goods from China to the United States. “So who’s responsible for the emissions?”

Germany has been among the countries that have pushed hardest to devise a climate change strategy for long-distance shipping. For years, experts have called for - at the very least - a switch from bunker fuel to diesel, which is cleaner but more expensive.

International shipping emissions are not covered by the Paris Climate Agreement, and plans to include them in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) were also put on hold. Instead, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol assigned responsibility for bringing down maritime greenhouse gas emissions to the IMO.

In April 2018, after years of failed attempts to implement meaningful emissions reduction measures, the IMO announced a climate change strategy to reduce international shipping’s GHG emissions, aiming to eliminate them entirely before the year 2100. The strategy has three key targets:

- increasing energy efficiency for all new ships

- lowering CO₂ emissions (per transport work unit) by at least 40 percent by 2030, and by 70 percent by 2050 (2008 baseline)

- “peaking” emissions from international shipping “as soon as possible,” cutting the annual greenhouse gas output by at least 50 percent by 2050 (2008 baseline), and phasing them out “as soon as possible in this century […] as a point on a pathway of CO₂ emissions reduction consistent with the Paris Agreement's temperature goals”

The strategy also includes a list of potential short, medium, and long-term measures that could be implemented to bring down emissions, such as an alternative implementation programme for low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels and market-based measures.

Several German maritime companies have welcomed the new measures. Hapag-Lloyd, Germany’s largest container shipping company, told the Clean Energy Wire that it regards them as "very positive. We’re pleased that the IMO rules are global, and thus apply to all players in every country. Until now, there’s been just local regulation that penalises some shipping companies but not others. Now there’s a level playing field.”

But Daniel Riegler of NABU is less enthusiastic, saying that “It’s not nearly ambitious enough. It’s a joke to think that these measures will decarbonise the entire sector by 2050, which is what’s needed to hit the Paris targets for transportation.”

Yet, the IMO strategy constitutes real progress and has the potential to accelerate research and development of low-carbon technologies. The strategy notes that technological innovation and the global introduction of alternative fuels and/or energy sources for international shipping will be integral to phasing out GHG emissions in the sector.

Ships often have a lifetime that considerably exceeds 20 years, and thus any new technological breakthrough will take a long time to actually show some effect. Accordingly, retrofitting existing ships for low-emission fuels is key but also difficult and expensive. Short-term measures to bring down emissions include simply letting ships move slower to save on fuel; hull coatings; or installing wind-assisted propulsion systems (e.g. kites) to make use of wind energy.

Researchers say the best bet for the long-term decarbonisation of freight shipping is to combine electric propulsion with synthetic fuels. A study by the Universtiy of Manchester examined a range of alternative fuels already under consideration for shipping. It found that most are compatible with modified internal combustion engines when blended, particularly for larger vessels. This could make existing ships less CO₂-intensive. Currently, the contenders include ammonia, liquefied natural gas (LNG), methanol and ethanol, liquid hydrogen, biodiesel, straight vegetable oil, and bio-LNG.

Experts say that switching to liquefied natural gas is no durable option in terms of lowering CO₂ emissions and could lead to a large number of stranded assets.

A 2017 report published by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) concluded that methanol and ethanol are “good potential alternatives” for reducing both the emissions and the carbon footprint of shipping operations. The obstacle is that they are not currently cost efficient, nor do they reduce both greenhouse gases and other pollutants, such as sulfur and nitrogen oxides.

Digitalisation and improved data use in water-borne freight transport will also play a significant role in reducing energy use by optimising the trade routes and the other related aspects of logistics. Research and development efforts will depend on the regulatory pressure arising from the future measures mentioned in the IMO strategy, but also on incentive and support schemes to be introduced by governments around the world.

At the 2017 UN climate conference (COP23), the German government announced its intention to commit 9.5 million euros to a joint project with the Marshall Islands to examine alternative low-carbon propulsion technologies. “This project is supposed to set an example for other countries in the [Pacific] region when switching to low-emission ocean transport,” said then environment minister Barbara Hendricks.