Power production at sea re-emerges as Energiewende cornerstone

The news from Germany has electrified global energy markets: in the country’s first offshore wind power auction, bidders offered to construct renewable power plants without receiving financial support for the first time ever. The auction, which took place in 2017, put the focus on a promising technology, whose enormous potential for power production companies and researchers is only about to be discovered. A renewable power source that used to be among the costliest when introduced in Germany not even a decade earlier has become one of the cheapest and most reliable forms of energy generation.

“We see an industry that has grown up,” said Uwe Knickrehm of the offshore wind power consortium AGOW at the first presentation of Germany’s offshore wind expansion in 2018. The “milestone” bid showed that harvesting offshore wind can make a substantial contribution towards reaching the emissions reduction goals Germany pledged under the Paris Climate Agreement. Significant advances in turbine development, and the solving of tedious grid connection problems for the power plants at sea, have given the sector a boost that now places it at the heart of the next stage of the Energiewende, the dual plan to phase out fossil and nuclear power generation in mostly landlocked Germany.

Although construction of the two support-free projects awarded in the first auction is only scheduled for 2025, the expected breakthrough in terms of costs has rewarded industry actors and policymakers in Germany and other countries for their years of persistent work in what once was considered an expensive niche technology by unshakeable energy transition enthusiasts.

Germany’s zero-cent bid heralded what appears to be a cascade of cost degression in offshore wind power, with the Netherlands pressing ahead with a full zero-support tender, and France and Denmark making plans to adapt their auction systems accordingly. The fall in support costs, down from 14.5 eurocents per kilowatt hour (ct/kWh) in Germany in 2012 to an average of just 0.44 ct/kWh in the first auction, has helped to establish offshore wind as a solid power supply. Although average support in the second auction bounced back up to 4.66 ct/kWh, partly due to specific constraints in this auction round’s rules, the increase in zero-support bids in Germany confirmed the impression that the technology has matured.

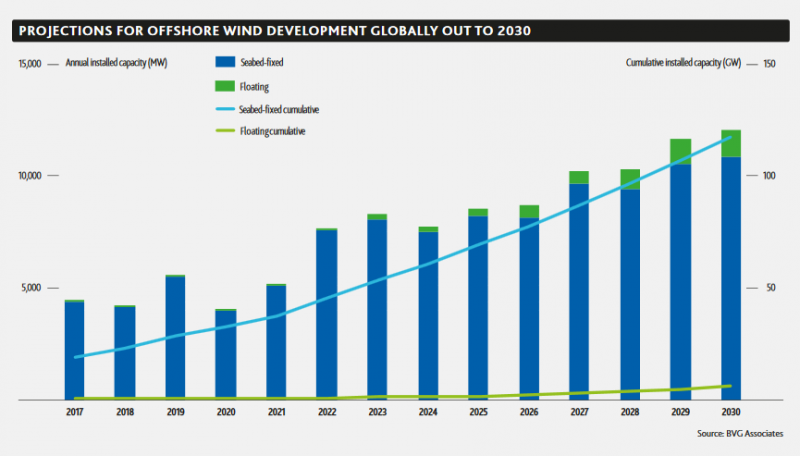

“Offshore is spreading like wildfire across the globe due to Europe’s patient, pioneering efforts to bring the technology to cost-competitiveness,” said Steve Sawyer, secretary general of the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), in the organisation’s annual ‘Global Wind Report 2017’. The GWEC said that prices for offshore projects to be completed in the next five years will be half of what they were in the past five years, and that this trend is likely to continue.

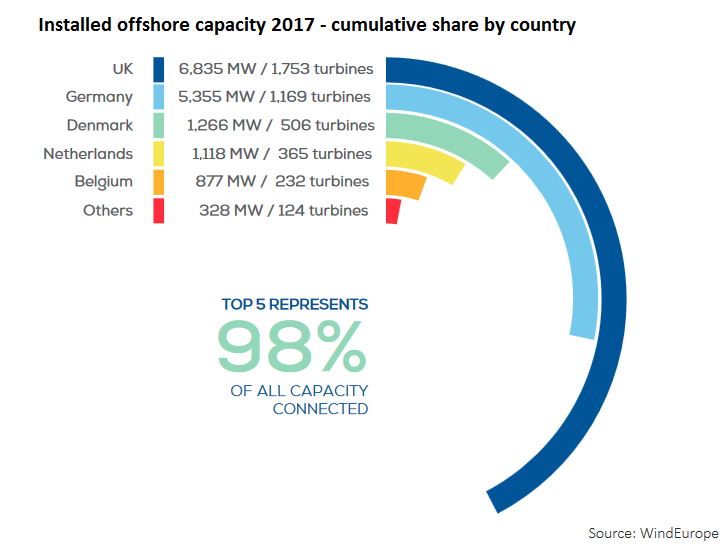

Together with the UK, Germany has led the charge in bringing down costs for offshore wind by adding big amounts of capacity since it started constructions on a large scale in 2009. The two countries combined account for 64 percent of all offshore capacity installed worldwide, and Germany alone for 40 percent of the capacity added in 2017. Altogether, 90 percent of the world’s offshore turbines were located in Europe as of 2018.

Back in 2014, things looked quite different for the country’s offshore wind industry. The fear of overshooting costs in the renewables build-up, coupled with grid connection delays, triggered policymakers to throttle down offshore expansion, and left investors in the dark over the domestic market’s future size. German utilities like RWE or EnBW subsequently announced their intention to put any further offshore power projects on hold.

In less than four years, however, wind power generation, under the difficult conditions at sea, has become a viable and affordable business that can fully compete with other forms of power generation, and also a cornerstone of the utilities’ energy generation portfolio for the future. The centralised and reliable form of power generation that in many ways resembles traditional power production with fossil or nuclear plants also appeals to policymakers. It does not face the same level of public opposition that has beleaguered onshore wind power expansion in recent years and a low output volatility provides better planning security than decentralised renewable power installations on land.

Technology & output - a sea change

Offshore wind power’s ascent to a key element in Germany’s energy transition was no foregone conclusion. While the country looks back on over 25 years of developing and integrating onshore wind power on an industrial scale (Find the CLEW dossier here), offshore wind still is a relatively new form of power generation, with the pilot project Alpha Ventus marking its 10th anniversary in 2019.

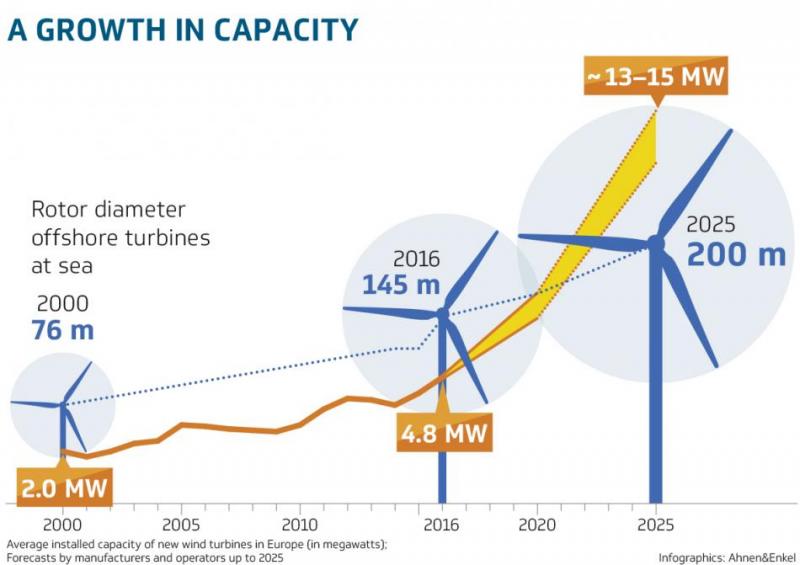

What started out as a testing field with a moderate 60 megawatt (MW) capacity was the prelude to a rapid expansion to 5,380 MW eight years later (find more data in the CLEW factsheet on Germany’s offshore wind power industry). This rapid growth was possible thanks to both the rising number of offshore wind farms and the growing capacity per turbine. The average offshore turbine installed in 2017 had a capacity of nearly 6 MW, almost a quarter more than just one year before.

And turbine development does not seem to be hitting a limit very soon. While the strongest turbines currently spinning in German waters reach about 8 GW capacity, US manufacturer General Electric is set to significantly increase this figure. It works on the world’s tallest offshore wind turbine, called Haliade-X, which will have a tip height of 260 metres, almost as tall as the iconic Eiffel Tower in Paris. Erected at sites with average wind conditions in the German North Sea, the 12 MW turbine will generate enough power to supply 16,000 average households, the company said. Researchers say turbine capacities of up to 18 MW are possible in the foreseeable future.

But even without these massive new models in place yet, the average offshore turbine already produces up to twice as much power as its onshore counterpart. Constant winds at sea ensure they can operate at high capacity for most of the year. Wind power research institute Fraunhofer IWES found that offshore farms feed into the grid even more steadily than previously thought and provide electricity practically all year round.

Although the German parts of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea are rather small, a study conducted by Fraunhofer IWES shows that, in a scenario of optimal output, offshore turbines could generate about one third of all renewable energy produced in the country by 2050. Irrespective of whether this high share will indeed be attained by the middle of the century, “the Energiewende will not be feasible without a significant contribution of offshore wind power,” Fraunhofer IWES concluded.

“Offshore wind farms by now are almost capable of supplying the grid’s base load,” Po-Wen Cheng, professor of wind energy generation at the University of Stuttgart, told the Clean Energy Wire. This means their output is dependable enough to continuously provide the minimum level of electricity needed to balance withdrawal and keep the grid stable. While even modern onshore wind turbines located far from the coast achieve an average 30 percent share of full load hours, the indicator of a power plant’s capacity utilisation, offshore turbines often reach up to 50 percent, Cheng says.

Fraunhofer IWES says that while feed-in prognoses for onshore wind power fail about 60 percent of the time, the respective figure for offshore wind is around 25 percent. The offshore installations’ baseload potential is up to ten times higher than that of the onshore turbines. In early 2018, British technology initiative Offshore Wind Accelerator issued a call for an innovation competition aimed at using offshore turbines for a ‘black start’ of the grid. This means the installations at sea should be able to restart the grid on land in case of a large-scale blackout.

Wind power scholar Cheng says centralised offshore wind farms offer an ideal supplement to the scattered, decentralised renewable power sources ashore. “Large-scale installations operate much steadier and can be used to full capacity more often.” However, he cautions that despite offshore turbines’ vast potential, they alone cannot guarantee a stable power supply for a large economy. “All it takes is a low-pressure area and the turbines will be turned off. The risk has to be spread over a larger area.”

Powerful offshore turbines scattered along Europe’s coastlines could function like a backbone for the cross-continental grid, Cheng says. The constant development of larger and more efficient turbines, leading to lower capital expenditure per MWh produced – or “more bang for the buck,” as some analysts have put it - substantiates the technology’s potential to contribute to the energy transition’s success.

The challenges of connecting offshore turbines to the onshore grid for several years have complicated the technology’s full breakthrough. Generating power at sea means it also has to be converted on the spot to ensure transmission happens as efficiently and frictionless as possible. Offshore wind farms in Germany are located further from the shore than those in most other countries and therefore typically come with their own converter station mounted right next to them, a complex and costly installation.

While a full connection to the land of existing offshore farms has been achieved as of early 2018, Germany still struggles with connecting the wind power-rich north of the country with industrial centres in the south (See the CLEW dossier on The energy transition and Germany’s power grid). Only then can offshore wind unleash its full potential as a grid-stabilizing energy source that provides baseload power.

But researchers and companies already mull bypassing grid connection problems of the future and convert power into gas directly at sea, boosting the technology’s reliability by storing excess energy for later use – an approach that could go on trial in a new test field Germany’s new government, consisting of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD), promised in its coalition treaty.

Policymakers could set sail to the high seas again

Germany’s government parties, which have been in power together since 2013, acknowledged offshore wind’s promising performance by including it in its “special auctions” for renewables, part of a bid to close the gap the country’s imperilled 2020 target of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent from 1990as far as possible. However, the coalition parties make the auctions contingent on whether the grid’s capacity is able to cope with additional expansion, and on having legal certainty over contentious state aid issues.

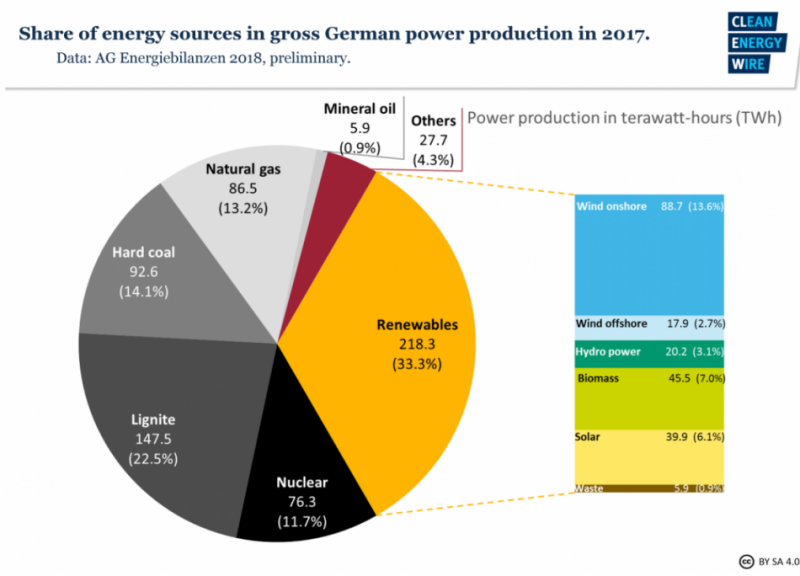

The treaty also promises to ramp up the share of renewables in German electricity consumption from 33 percent in 2017 to 65 percent by 2030, as the country’s nuclear plants are set to go offline completely by 2022, and coal power will have to be phased out gradually to reduce emissions. Meanwhile, efforts in the field of sector coupling, the integration of the transport and heating sectors into the electricity sector (see the CLEW factsheet), are expected to intensify in the decade ahead, and push power consumption up.

“We cannot achieve this without offshore wind power,” Johann Saathoff, the SPD parliamentary group’s energy policy coordinator, said at an industry event in Berlin in April 2018. “If the coalition treaty’s goal of 65 percent renewables is to be achieved, we’ll need a renewable power capacity of 240 GW.” This means offshore wind power expansion should accelerate to 2.5 GW per year, equal to about half of the total capacity in 2018, the Social Democrat, who hails from the northern wind power state of Lower Saxony, said. “Offshore wind power no longer is a prestige project or an expensive hobby – it is now industrial policy.”

At the proposed rate, Germany’s overall offshore capacity would grow well beyond 25 GW by 2030. Government planning , however, still sets more moderate goals. It foresees tripling capacity to 15 GW by 2030, equivalent to the output of about twelve average nuclear power plants. According to lobby organisation Foundation Offshore Wind Energy, this could cover the power demand of 15 million average households.

But Hermann Albers, head of the German Wind Energy Association (BWE) lobby group, said at a presentation of the industry’s expansion figures that the government’s goal is insufficient to meet the challenges ahead. “I don’t think the government will be able to uphold its cap on expansion, both offshore and onshore.” Albers’s assertion is reflected in the so-called Cuxhaven Appeal, issued by the economy ministers of Germany’s coastal states, cities, and the offshore wind industry.

The group calls for ramping up capacity to at least 20 GW by 2030 and 30 GW by 2035. Its signatories also say that increased research and development funding, grid development, and better maintained and expanded ports are needed to help the country boost economic development and reduce emissions. Proponents of a quicker expansion point at the government’s original plans from 2002, which stipulated an expansion to 25 GW by 2030.

But in 2013, the then-environment minister and now economy and energy minister, Peter Altmaier, pulled the brakes on offshore expansion by introducing the so-called “power price brake.” The reform of the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) was aimed at curbing what Altmaier feared could amount to a a trillion in costs of the Energiewende, bringing onto himself accusations of using a unfounded cost estimate (Read CLEW’s Altmaier profile here). The reform entailed reduced expansion goals and a makeover of the support system, resulting in feed-in remuneration of up to 19 ct/kWh. It remained in place until 2017, when it was succeeded by the auction system.

The policy turnaround delivered a blow to many renewable energy companies, and not only to those active in offshore wind power. Several cities and municipalities in Germany’s coastal regions still grappling with the shipbuilding industry’s fading importance invested heavily in the promise that was offshore wind power.

Harbours in cities like Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven or Rostock had been converted to make them suitable for handling the massive turbine elements and foundations, transport and grid capacities were ramped up to meet new standards, and workers were retrained for what was supposed to become a success story of an almost fully integrated industrial production chain in a structurally lagging region. They now feared these investments could get stranded.

But regardless of the calls for ramping up offshore wind expansion over the next decade, the government’s long-term plans foresee a renewables share of 80 percent of power consumption by 2050. Research institute Fraunhofer IWES has estimated that Germany’s installed offshore capacity would have to increase about tenfold over the next three decades to 54 GW to meet this goal. “This means that all currently identified areas in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea have to be used for construction,” it said.

Given that offshore wind farms encounter relatively modest resistance compared to their onshore counterparts, which intensified in recent years as Germany’s transition to renewable power generation comes into full swing, political decisions can be implemented in a far more undisturbed manner at sea. Addressing an industry gathering, Martin Skiba, head of the industry association AGOW, summarised the expected capacity expansion in Germany and its neighbourhood by predicting that “the North Sea will become one of the biggest construction sites of this century.”

But the prospect of extensive offshore growth on this scale has raised concerns among conservationists. They face the balancing act of embracing a promising clean energy source, while at the same time trying to avoid the sea’s “industrialisation,” as the power plants are built in fragile marine habitats largely hidden from public scrutiny (see the CLEW factsheet on environmental concerns about offshore wind power).

Risk & return – From uncertain investment to cost breaker

The drop in the costs of offshore energy generation has fired up the imagination of policymakers and big energy companies, who have come to realise that generating power with massive centralised wind farms at sea comes close to their traditional model of centralised production with huge nuclear, coal, or natural gas plants (see the CLEW dossier on Utilities and the energy transition).

Contrary to onshore wind power in Germany, which to a large extent is in the hands of citizen cooperatives, small companies, and municipalities as big utilities generally were too slow to embrace the trend emerging since the 1990s, offshore wind ownership structures largely mirror the old pattern of big and financially strong investors holding all the means of production. This is due to the high barriers to entry that come with establishing a whole new industry branch from scratch in an environment that requires high-level skills and materials, something that smaller actors can hardly muster.

Alpha Ventus, the pioneer project from 2009, already exemplified the technical challenges and the associated financial risks offshore investors are bound to face. The project was executed jointly by utilities E.ON, Vattenfall, and EWE, which together invested about 250 million euros in twelve turbines, a substation, and the required grid connection. Additionally, the project received state aid of about 30 million euros from Germany’s environment ministry (BMU). Given the considerable technological challenges entailed in installing an offshore wind farm, the ministry argued it would offer crucial insights for rolling out the technology on a large scale in an economically viable and ecologically acceptable way that justify high fixed costs.

The difficulties at sea have led some turbine manufacturers to refrain from going offshore. These where high waves, storms and even ice floes create a challenging environment. The construction of foundations far away from the shore in deep water leads to long shutdown periods in case of disturbance that is made more likely by corrosion in salty air. Enercon, Germany’s leading onshore turbine manufacturer, says that it decided early on to ignore offshore projects for entrepreneurial reasons. “There’s just too much risk. The prospects didn’t justify the additional development efforts that are needed,” company spokesman Felix Rehwald told the Clean Energy Wire.

Efficient operation and maintenance remains a key challenge in offshore wind farms, not least because a standstill of the turbines costs the operators large sums of money. Regular inspections of the installations and their grid connections by boat or helicopter account for about a quarter of the total costs, whereas turbine construction makes up about a third of the total costs, the BWE says. In onshore projects, turbines account for about two-thirds and maintenance for “only a few percentage points” of the total costs, the association adds. The higher risk investors run offshore means that there needs to be a higher profit margin to make offshore projects attractive vis-à-vis onshore wind farms.

Germany’s first large-scale commercial offshore wind project, the 400 MW Bard 1 farm commissioned in 2013, illustrated much more clearly the dangers awaiting investors offshore. The park is located 90 kilometres off the coast in an average water depth of 40 metres. This in itself poses significant physical hurdles. But after initial problems with transmitting the generated power to the land, a fire at the converter station and the ensuing standstill of the farm pushed costs up to nearly three billion euros, equalling generation costs of almost 7.5 million euro per MW of power.

Bard, the overstrained project operator, paid dearly and subsequently went out of business. Ownership was passed on to a consortium owned by Germany’s HypovereinsBank, now part of Italy’s UniCredit. But in spite of the high costs, the project, originally planned to operate for at least 25 years, is still economically feasible, the consortium said in an article in the newspaper Die Welt.

But the costs of offshore wind farms have nonetheless proven to be better calculable than those of other large-scale energy projects. In a study conducted by the Hertie School of Governance calculated the actual costs of nuclear plants on average well over 100 percent higher than initially planned, while the average cost overshooting for both offshore and onshore wind amounted to about 35 percent on average.

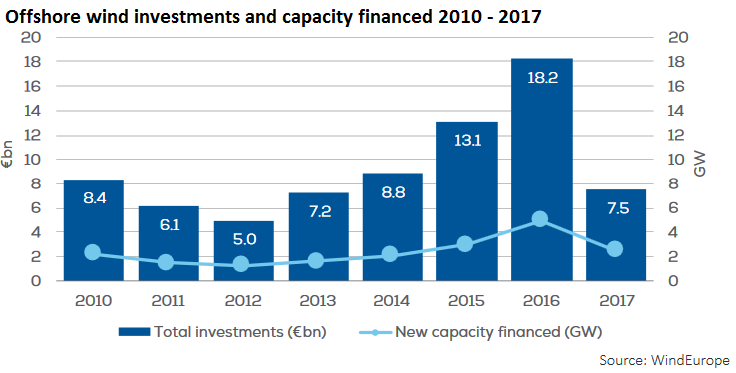

According to a study commissioned by the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, the average investment cost per MW in Germany stood at 4.2 million euro in 2013, and could fall to 3.4 million euro by 2023. The figure could dwindle even faster in the next years, as crucial advances in turbine and construction technology have taken place since then and might halve over the next five years, industry association GWEC said in its 2017 report.

However, despite the downward trend in offshore wind power costs, the sector dominated European spending on renewables in 2017, according to a study published by the Frankfurt School of Finance. With a total investment of nearly 26 billion euros, it accounted for well over 40 percent of total renewables spending.

German utility EnBW, one of the two utilities making a zero-subsidy bid in the first auction, says given the long implementation time of offshore projects, reliable political conditions are the most important condition for any investor. From the first steps in the planning process to finished construction, offshore wind farms take five to ten years to build. “Market players have to be able to prepare for the future,” the company told the Clean Energy Wire.

EnBW says its expectations about future power prices, which apart from technological developments define the support required, to a large extent hinge on policy choices. The company says it is convinced that its parameters for the bid still are completely valid. “And the bidding behaviour of our competitors since then suggests they have similar or even more optimistic expectations,” the company said.

Henrik Poulsen, CEO of the other zero-support bidder, Ørsted from Denmark, seconded this assessment: “We’ve thought this through and we’ve never built a wind farm that burns money,” he told the newspaper Handelsblatt in an interview. He added that all renewable energy projects will eventually have to be operated without support, which could be achieved more easily “if there was a reasonable price for CO2.”

The drop in the cost of offshore wind, but also of onshore wind and solar power, has emboldened Germany’s new economy minister Altmaier to predict the end to the country’s renewables support scheme. “Today we can build renewable energy installations at a fraction of the costs of the past,” Altmaier said at the Berlin Energy Transition Dialogue 2018, arguing the renewables sector will be able to compete with other power sources on its own by about 2022.

But the GWEC cautions that it is far from clear that the zero-support bids herald a wave of similar offshore wind power installations. Zero-support bids so far had been “relatively unique and not necessarily transferable”, it argues, adding that the bidders’ projections of future power prices and technology standards “could prove to be wide off the mark”. If the two companies ultimately decide not to follow through with their bids, the fines they face for abandoning their plans “are relatively small”, the association says.

Gunnar Groebler of the Swedish energy company Vattenfall also says the cost drop has to be taken with a pinch of salt. He cautioned that “aggressive” zero-cent bids were sometimes made merely to secure capacity and without regard to profitability. In a Dutch auction, Vattenfall secured a bid in April 2017 for what is expected to become the world’s first operating zero-support offshore wind park by 2022. “Market price risks, however, remain significant,” Groebler told journalists ahead of an offshore industry conference in Berlin. “The carbon price debate or the speed of Germany’s coal exit are decisive factors here,” the manager said, arguing that this uncertainty warranted to sustain the support regime for the foreseeable future. “If you have very different price development scenarios, some sort of financial security will be needed.”

However, wind power market analyst Heiko Stohlmeyer of the consultancy PwC argues that in spite of the first projects’ favourable surrounding conditions, the zero-support bids nevertheless have left their mark on the market and will inevitably influence the general price developments of future projects. “Apparently, this is the course the market will be taking,” Stohlmeyer told the Clean Energy Wire. But the analyst also warns that the renewed zero-cent bids in the auction point to the market’s competitive pressure rather than to actual drops in cost. “They are a bet that the price level will rise above generation costs once the wind farms start operating.” If this effect does not set in, the project’s implementation is questionable, he said.

It is plausible that a sweeping drop in offshore wind costs is indeed in the offing, Stohlmeyer added. In this case, the expansion goals must be adjusted, he said. “It would be reasonable to think about that. Practically no renewable technology in Germany has a comparable potential for further expansion.” But the analyst cautioned that it was even more important for Germany’s new government to end the regulatory volatility, which he said had been prevalent in recent years. “This would probably benefit the Energiewende as a whole,” Stohlmeyer said.

Industry perspectives – Global harvest

The swaying of Germany’s expansion goals and the changes in its renewables policy with a switch to auctions have unsettled the country’s fledgling offshore wind industry. Nevertheless, employment and revenues have grown in recent years. Today, about 20,000 people work directly in the offshore wind sector. This equals about 40 percent of Europe’s offshore wind workforce, which generated two billion euros in sales in 2017.

The sector’s emergence partly owes to the companies’ high export share of over 70 percent, which makes manufacturers less dependent on developments on their home market. While neighbouring countries, like the UK or the Netherlands, have so far been the primary destinations for German turbine technology, foundation models, or submarine cable components, the focus is now set to shift to the coastal waters off North America and East Asia.

The US has licensed the construction of about 15 GW of capacity, and countries like Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, or Vietnam are about to take, or have already taken, concrete steps to enter the offshore wind market. But as in many other industries, China’s hunger for electricity is set to overshadow the developments worldwide. “China will be the number one growth market in a few years and no other country,” said industry association AGOW’s Martin Skiba. He considers the growing reliance on offshore wind a safe choice, provided that the impetus to establish the technology is not interrupted. “Offshore wind can deliver immense amounts of energy. We just need the right political conditions.” Skiba said it was reasonable to believe that offshore wind power will see “a golden age” in this century. “But the jury is still out on how quickly the roll-out takes place,” he added.

German policymakers must understand that this will not only benefit coastal regions but helps integrating the energy transition into industrial procedures across the whole country, Social Democrat Saathoff says (See the CLEW dossier The energy transition’s effects on the economy).

“Much of the systems engineering is done in southern Germany and in the eastern states. This has to be made known better.” Many of his colleagues still associate offshore wind power with cost overshooting and incalculable investment risks, Saathoff said. This had to be corrected to stabilise the sector for the great leap forward in emissions reduction and renewable power supply the German government has envisaged for the next decade.

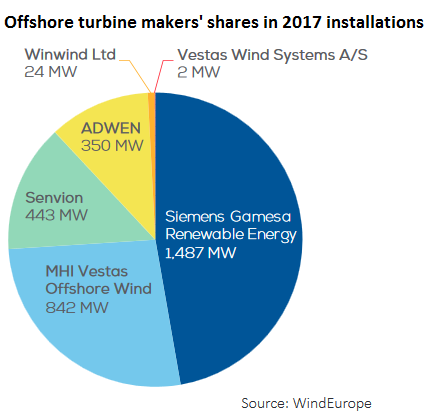

Private companies already jump onto the sector’s global bandwagon. One of the great beneficiaries is Siemens-Gamesa. The merger of Spanish turbine maker Gamesa and the wind power division of Germany’s largest industrial conglomerate, Siemens (see the CLEW factsheet on Siemens’s changing strategy for the Energiewende) has become a major driver of the offshore wind power market. The new entity ranked fourth in total installed capacity in 2017, according to an analysis conducted by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Accelerated offshore expansion is set to bring Siemens-Gamesa further up in the rankings, the analysis suggests.

In early 2018, the company secured a construction contract for what is to become the world’s largest contiguous offshore wind farm named Hornsea in an 870 square kilometre area in the North Sea off the coast of England. The profitability of the company’s offshore business grew significantly in 2017. This was mainly due to higher margins, the conclusion of existing projects, higher capacity utilisation, and higher earnings in the service segment.

For all its flaws, Siemens considers Germany’s Energiewende policies a decisive factor behind its rapid emergence in this growth sector. “As an offshore wind energy pioneer, it’s of course only thanks to the German energy transition and European climate diplomacy that we could become the globe’s most important technology partner for wind energy,” spokesperson Florian Martini told the Clean Energy Wire.

And it is not only German manufacturers who set out to capitalise somewhere else on the experiences gathered in the North Sea and the Baltic. The partly state-owned utility EnBW, one of the first auction’s zero-support bidders, used to be heavily invested in nuclear power and it now stands among the leading offshore wind power operators. It is eyeing investments in the US and in East Asia, and has recently made its first offshore investment outside Europe with three projects in Taiwan.

“Offshore wind expansion will be a central building block of our strategic repositioning,” the company told the Clean Energy Wire. Fierce competition in Europe means that the next growth story will primarily occur elsewhere, EnBW said, adding confidently that its “valuable know-how” will help it establish itself far away from its home turf.

However, greater exposure to the global markets also rings in a new round of challenges for the German offshore sector, the national wind industry organisation BWE has warned. “The market entry of Chinese manufacturers will come,” said BWE head Albers. He argued that companies that only begin to establish themselves in the offshore business could quickly catch up in producing standard components at competitive prices. Germany and other offshore pioneers could only bank on an advantage in technology development that must be preserved, the wind power lobbyist said. A vital home market was an important driver for that, he added. “We need a strategy that focuses on innovation. And it needs to be integrated into a European renewables strategy.”