Set-up and challenges of Germany's power grid

Germany is experiencing a continuous growth in renewable power generation, causing an upheaval in the traditional supply chain for electricity.

In 2020, renewable sources, mostly from biomass plants and volatile sources, such as wind and solar PV, covered over 45 percent of German power consumption.

The grid system, which was built to deliver electricity from large power stations (via the transmission network) to some large (industries) but mostly small consumers (households - via the distribution network) is being upended by hundreds of thousands of small renewables installations (over 1.7 million solar PV installations and over 29,000 onshore wind turbines), which are feeding into the distribution grid at lots of decentralised locations (see graph below).

Source: EPRS 2016.

Keeping the grid stable during times of high influx of variable renewables and organising the interaction between the transmission and distribution grids are among the challenges faced by Germany’s grid operators.

Transmission grid

The total length of Germany’s transmission grid is around 35,000 kilometres. It transmits power with a maximum voltage of 220 kilovolts (kV) or 380 kV. Most of the power lines use alternating current, but the new transmission lines between northern and southern Germany, planned to be completed by 2025, will use the more efficient high-voltage direct current (HVDC) technology.

The transmission grid is used to transport electricity over large distances, taking power from where it is produced to areas of demand, as well as exporting power abroad. Currently, just 0.4 percent of the German transmission grid is laid below ground. In response to public protests against overland powerlines and pylons, new legislation has given priority to underground cables, although this technology is more expensive to install and maintain.

Transmission grid operation

In Germany, the maximum voltage transmission grid is owned by four transmission system operators (TSOs) - TenneT, 50Hertz, Amprion, and TransnetBW -, which are responsible for the operation, maintenance, and development of their respective sections of the grid. It is their job to regulate the power supply, including balancing fluctuating power from renewables with more predictable conventional generation.

Power suppliers must pay the TSOs a “grid fee” for the use of their network, which is ultimately passed on to the consumer. This covers infrastructure costs, invoicing and metering and levies, including for combined heat and power (CHP) plants, and the levy for interruptible loads, which is paid to large power consumers for them to be ready to reduce consumption in times of shortage, with a higher rate being paid should they in fact have to do this. The grid fee also covers the cost of operating the grid and keeping it stable, including voltage and frequency control.

Because TSOs have monopolies in their areas of operation, the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) puts a cap on what they can charge in grid fees.

The four German transmission grid operators

Amprion GmbH

Amprion operates the grid in western Germany from Lower Saxony down to the borders with Switzerland and Austria, across seven German states (11,000 km).

Amprion also coordinates load and frequency between the four German control areas, and is responsible for coordinating exchange programmes both for the German transmission grid as a whole, and for the northern part of the European UCTE (Union for the Coordination of the Transmission of Electricity) interconnected system (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary). Amprion operates the new connection with Belgium (ALEGrO).

RWE, one of Germany’s biggest utilities, holds a minority stake in Amprion.

TenneT TSO GmbH

TenneT operates 40 percent of the German grid running through the centre of the country from north to south, from Schleswig-Holstein though Lower Saxony and Hesse, down to Bavaria in southern Germany (approx. 10,700 km). It is owned by Dutch company TenneT, which is also responsible for managing the transmission grid in the Netherlands. TenneT also operates cross-border interconnectors between Germany and the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Austria, and the Czech Republic. In 2021, it launched a first direct current subsea cable link to Norway (NordLink). TenneT is responsible for connecting offshore wind parks in the North Sea to the German grid.

50Hertz Transmission GmbH

50Hertz operates the transmission grid in northern and eastern Germany (approx. 10,000 km), which is directly connected to the grids in neighbouring Poland, the Czech Republic, and Denmark. 50Hertz coordinates the interaction of all players in the electricity market in the federal states of Berlin, Brandenburg, Hamburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. More than 40 percent of the installed wind energy capacity are located in the network area of 50Hertz. The TSO had a share of 60 percent renewable power in its grid in 2019. It is aiming to run the system with 100 percent renewables by 2032. 50Hertz is also responsible for connecting offshore wind farms in the Baltic Sea to the German grid.

TransnetBW GmbH

TransnetBW operates the transmission grid in Baden-Württemberg (3,200 km). The TransnetBW grid is connected to the French, Austrian, and Swiss networks.

Transmission grid planning

The Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur) provides regulatory oversight to ensure that the grid is available for use by all market players without discrimination, and to keep charges for its use in check. It is also responsible for implementing legislation designed to accelerate the development of the transmission grid.

Grid expansion planning entails a series of steps.

- Every two years, TSOs prepare a scenario framework, which presents the likely future developments in Germany’s power mix and power demand. The time frames for the scenarios drawn up by the four TSOs range from 10 to 20 years. The scenarios are submitted to public consultation, and are signed off by the Federal Network Agency.

- Based on the scenario framework, TSOs then together propose (also every two years) a Network Development Plan (NEP), which lists measures that should be taken to improve and expand the network in order to keep the power system running at an optimum levels. The plan also assesses the potential environmental impacts. Following a public consultation, It is evaluated, approved and overseen by the Bundesnetzagentur.

- At least every four years, the confirmed NEP and an environmental sustainability report are passed on by the Federal Network Agency to the government. The German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy uses it in drafting the Federal Requirements Plan (Bundesbedarfsplan). The grid improvement measures and a list of required maximum voltage transmission lines included in the law provide the basis for subsequent planning.

To accelerate grid expansion, a range of new laws have been enacted since 2009, when the Power Grid Expansion Act (EnLAG) came into effect. If an expansion project is limited to one state, it is the responsibility of that state’s authorities to permit the corridors for new cables. If the project crosses state or international borders, the Grid Expansion Acceleration Act (NABEG) stipulates that the federal government, with help of the BNetzA, takes on this task. This planning is subject to several rounds of public consultation.

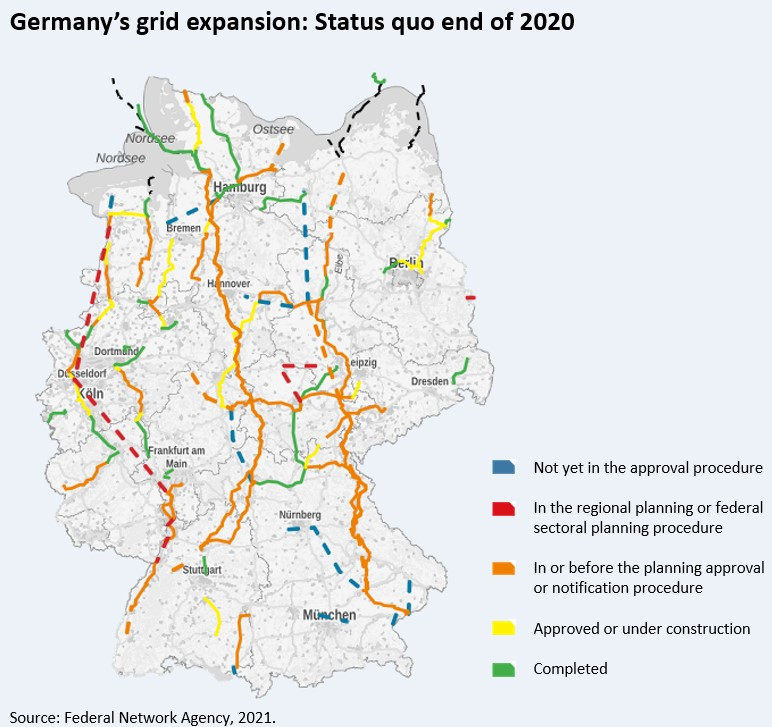

The two pieces of legislation that guide the grid expansion in Germany are the Bundesbedarfsplan Gesetz (2019) and the 2009 Energieleitungsausbau Gesetz (EnLAG). They require the building of 7,783 km of new maximum voltage transmission lines. This includes the construction of four direct current transmission lines connecting the windy north with the industrial west and south of the country. By the end of 2020, 712 km out of the total 7,783 km had not yet started the planning precudure; 1,185 kilometres were in the regional planning or federal sectoral planning procedure; 3,533 kilometres were before or in the planning approval procedure; 734 km had received planning permission and were being built; and around 1,600 kilometres have been completed.

Challenges

Bottlenecks in the transmission grid (See Dossier Grid) and a rise in re-dispatch costs (See Factsheet Re-dispatch costs) are the main challenges for transmission grid operators in Germany. In order to alleviate the problems until the new direct current transfer lines are completed, the federal government has set up a stakeholder process to increase the load factor of the existing grids. These technical solutions include overhead line temperature monitoring, phase-shifters, re-dispatch optimisation, and FACTS (flexible alternating current transmission system) technologies. They are mostly aimed at getting more information about the power lines and improving their controllability through technological updates, thereby enabling them to carry more power.

Distribution grid

The distribution grid brings power directly to consumers and is operated by a large number of regional and municipal operators (around 880). The total length of Germany’s distribution grid is 1,679,000 kilometres. It transmits power at three different voltage levels:

- The high voltage grid (approx. 77,000 km) transmits power at 60 kV to 220 kV and is used for the primary distribution of electricity to transformer substations in population centres or to large, energy-intensive companies in the industrial sector.

- The medium voltage grid (approx. 479,000 km) transmits power at 6 kV to 60 kV to smaller regional substations and larger consumers, such as factories or hospitals.

- The low voltage grid (approx. 1,123,000 km) transmits power at 230 V or 400 V to private households and other smaller private consumers.

Around 80 percent of the power distribution lines run below ground.

Challenges

The distribution grid can suffer from bottlenecks just as much as the transmission grid, but a major grid expansion is not the solution. However, with 95 percent of the renewable power generators connected to the distribution grid, there is a clear need to update the infrastructure to cope with the increasingly bi-directional flow of power. But dealing with prosumers (households - and soon more and more electric vehicles - that not only consume power from the grid but also feed electricity into it from their rooftop solar PV panels) requires the installation of new (smart) technology. This involves investment in smart meters or local distribution substations, more accurate weather forecasting equipment that inform the grid management, and a range of new software – all to make the grid more transparent and controllable from afar. The lower the voltage level, the less information and communication technology has been installed, simply because it wasn’t needed before prosumers entered the market.

In 2015, the federal parliament passed a law on the digtalisation of the Energiewende, which stipulates the installation of smart meters.

The rollout of new technology has been slowed down by delays in technology development and concerns about data security.

There are over 800 distribution grid operators, some of which belong to large conglomerates like E.ON, Innogy, or EnBW, while others are small regional utilities. They all have to aquire the technology and know-how and plan the installation of hundreds of thousands of smart meters.

An example: In April 2018, distribution grid operator HanseWerk in northern Germany announced its intention to install 665,000 smart meters by 2032. The grid operator is also working on an online platform (called ENKO) for trading local flexibility options. This would enable the synchronisation of locally generated renewables with local consumption, thereby freeing up grid capacity.

Reliability

Germany’s power grid ranks among the most reliable in the world despite the rapid expansion of renewables. Its System Average Interruption Duration Index (SAIDI), which measures the average yearly downtime per customer, amounted to 12 minutes in 2019, a slight decrease from almost 14 minutes in 2018, according to the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA). Compared to 128 minutes in the US (2016), 53 minutes in Great Britain, 92 minutes in Greece, 54 minutes in Spain, 41 in Italy, 50 in France and 192 in Poland (2014 data). When looking at the interruptions including exceptional events, the difference gets even bigger with Germany's consumers spending an average 12 minutes withouth power, compared to 92.5 minutes in Great Britain, 122 minutes in Greece, 52 minutes in Spain, 93 in Italy, 51 in France, 205 in Poland (2014 data) and 314 minutes in the US (2016).