Germany may have to buy way out of EU climate goal - ministry paper

Germany will likely miss its binding EU target of cutting emissions from sectors not included in the EU's emission trading system (ETS), and will have to buy emission rights from other countries, according to an internal paper from the German environment ministry, seen by Clean Energy Wire.

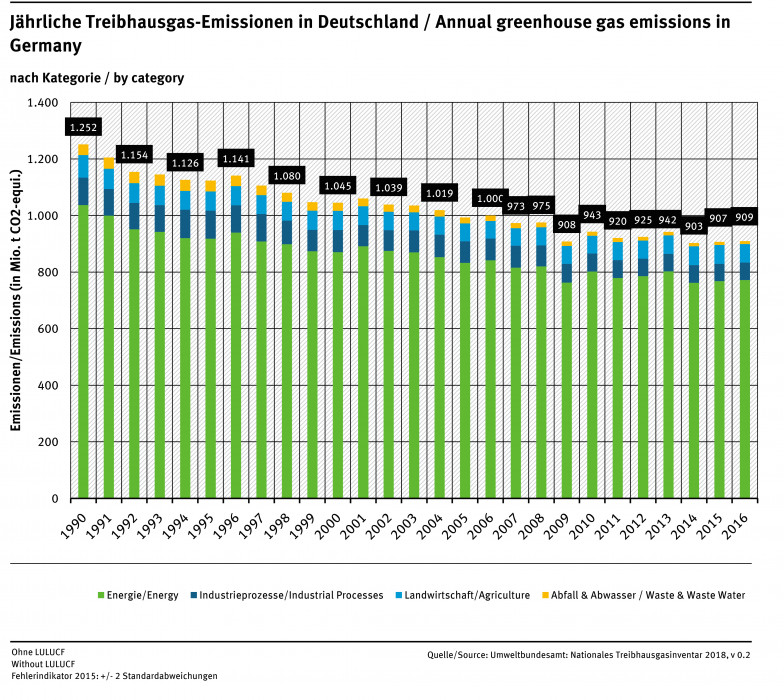

Figures compiled by Germany's Federal Environment Agency (UBA) also confirm that emissions rose in 2016, for the second year in a row. That also casts further doubt on Germany's prospects of achieving its national 2020 climate target. The country's negotiating coalition parties of Chancellor Angela Merkel's conservative CDU/CSU block and the Social Democrats (SPD) recently agreed on a blueprint that could postpone the reduction target of 40 percent compared to 1990 levels into the 2020s.

Reducing carbon emissions is part of Germany's energy transition policy, a dual move to cut greenhouse gas emissions while phasing out nuclear power. The environment ministry warned in October 2017 that under current policies, the reduction would amount to between 31.7 and 32.5 percent by 2020 instead of 40 percent. It currently stands at 27.3 percent, the UBA says.

By contrast, the country has rolled out renewable energy sources faster than projected, and now covers more than 35 percent of its electricity consumption with renewables. However, rising emissions from the transport sector and continued power generation from lignite, Germany’s most polluting energy source, mean emissions are likely to have stagnated again in 2017, according to energy market group AG Energiebilanzen estimates.

Under the EU’s effort sharing decision, Germany must cut emissions from non-ETS areas such as transport or agriculture by 14 percent by 2020 compared to 2005. The overall goal is for the EU to reduce emissions by 10 percent across the union. The German environment ministry paper, first reported by energy and climate newsletter Tagesspiegel Background, says even last year’s projection of a reduction of around 11 percent looks now “optimistic”.

“Germany must do much more to meet its goals, mandated by European law, and its responsibility in climate policy,” the paper says. Countries such as Sweden, France and the Netherlands look set to exceed their emissions reduction targets.

Yet Germany could cover the shortfall for 2016 and 2017 with earlier surpluses, and “borrowing” from future cuts. “For 2019 and 2020, the purchase of additional emission rights from other countries will be necessary,” the ministry said.

At an event held by industry association BDI on 18 January, state secretary for the environment Jochen Flasbarth warned that Germany should expect these expenses. “We will not even meet the EU- 2020 target. We will have to pay for the first time,” Flasbarth said.

Buying its way out of the EU's climate goal is a highly unusual move that only the tiny island nation of Malta has used so far, Tagesspiegel Background reports. According to newspaper taz, Germany could buy allowances from countries that have not used their entire CO2 budget, such as Hungary or Croatia. At current ETS prices of between 5 and 7 euros per tonne, the bill could amount to up to 350 million euros, the taz says.

National 2020 goal also out of reach

Meanwhile, recent figures by environment agency UBA confirm earlier reports that greenhouse gas emissions have been rising in recent years. Total emissions rose for the second year in a row in 2016, the agency says. Germany emitted 909.4 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent in that year, up by 2.6 million tonnes compared to 2015, the UBA says.

Power sector emissions actually fell in 2016, but this was offset by an increase in emissions from transport, which in 2016 were even higher than in the base year of 1990. "We need a new approach in the transport sector,” UBA head Maria Krautzberger said.

Rising emissions not only make Germany's own domestic 2020 goal of reducing emissions by 40 percent increasingly unrealistic, but sustained inaction also puts the country's 2030 goal of cutting CO2 by 55 percent at risk, Krautzberger said. The UBA calls for rapid measures such as throttling coal-fired power generation and a quota for e-cars to counter this trend.

“Germany has become self-indulgent,” WWF climate and energy policy expert Michael Schäfer said. Unlike the national 2020 goal, Germany’s contribution to the EU climate target is legally binding - albeit less ambitious, he adds. “Missing two important 2020 goals at once would amount to a bankruptcy of the grand coalition’s climate policy,” Schäfer argues, referring to the outgoing German government now in talks to extend their leadership for another term.

If a country as rich as Germany “sinks to the bottom of EU climate politics, this gives a fatal signal to all other states,” Schäfer says. The negotiating coalition parties must therefore include in their deliberations an emergency programme centered around a coal exit to meet the 2020 goals, he says.

"Fake climate goals"

In a paper agreed after exploratory talks, Chancellor Merkel's conservative alliance and the SPD have instead softened their commitment to the 2020 goal. While officially maintaining the goal, the parties have said they aim to get as close to it as possible while focusing on steps to achieve the country’s 2030 emissions reduction goal. They are now entering formal talks to renew their grand coalition, which has been in power since 2013.

The wording in the coalition paper sparked sharp criticism from environmentalists at home and abroad. However, CEO of German utility E.ON Johannes Teyssen said the move was fitting and brave, adding that the focus should now be on effective measures to cut emissions. “So far, solutions to this are absent in negotiations,” Teyssen told energy managers at a conference organised by business daily Handelsblatt. He said the European emissions trading system (ETS) was “a failed instrument” that could not do enough to reduce emissions, and that “an effective CO2 price” on a European level, backed by a national carbon tax would be “the most powerful instrument” for climate protection.

Ernst Ulrich von Weizsäcker, co-president of the Club of Rome, struck a similar tone. In a newspaper interview he said German politicians had endorsed a “fake climate goal” that could not have been met. He added that policymakers have now "decided to ramp up and accelerate their efforts."

The parties in coalition talks have proposed that a commission be charged with devising concrete measures, including a timeline for an exit from coal-fired power generation.