Quarrelling German coalition treads lightly on climate as economy dominates EU election agenda

Five years after the previous European election, Germany and the rest of Europe will face a vastly changed political environment when they go to the polls to elect a new European Parliament in June. Since the previous vote in 2019, Europe has gone through a sapping pandemic, seen the return of a major international war on its own territory, and coped with soaring inflation fuelled by skyrocketing energy prices. Olaf Scholz’s tripartite coalition of the Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) took over in late 2021, shortly before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine rocked the continent’s balance of power.

One month before it faces its first nationwide vote in office, Scholz’s “traffic light coalition,” named after the three parties’ colours, continues to pursue a path of constant internal bickering. In a poll released in late April, almost 90 percent of respondents said the mood within the coalition appears to be downbeat. Yet, about three quarters also said they believed that the coalition will not break up before the next federal election, scheduled for late 2025.

This markedly critical view may underplay some of the coalition’s achievements. Overall, the government’s management of the energy crisis can be described as reasonably successful, given the scale of the challenge to replace its most important energy trading partner in a matter of months. No major supply shortages occurred, the country has so far managed to withstand a recession without mass layoffs or bankruptcies, and it starts seeing the first signs of an economic recovery.

Meanwhile, tumbling energy prices have begun putting checks on inflation rather than spurring it. In addition, the coalition could chalk up a record output by harnessing renewable power, and can boast the lowest coal use in more than half a century along with a massive drop in greenhouse gas emissions – even if this has been partly caused by the recession. Last but not least, it also completed the country’s phase-out of nuclear energy, marking the end of decades of debate.

An extreme drought and international climate protests put climate and energy centre stage in Germany and most of Europe in 2019. Also in 2021, Scholz campaigned successfully to inherit his predecessor Angela Merkel's inofficial title as "climate chancellor." But the tone is different this time around - and climate action is not mentioned nearly as much as it used to be in the two previous votes: “Other topics dominate the agenda at this election,” including migration, security policy and economic competitiveness in the global race for transforming industry, said Luise Quaritsch from EU policy think tank Jacques Delors Centre (JDC). However, reconciling climate action with economic growth and avoiding social hardships continue to feature as aims in almost all election programmes, Quaritsch added. While the FDP and the largest opposition party, the conservative CDU/CSU alliance, focused on reduced bureaucracy and developing the EU Green Deal “to be more industry friendly,” the SPD and the Greens rather focused on the transition’s social dimension and boosting state investment, she argued.

The country faces the long-term structural challenge of lasting higher prices for industry that threatens to undermine the success of many of its manufacturing heavyweights. Even if Scholz’s coalition only bears limited responsibility for decades of energy policy leading to the current predicament, how it manages this key period is carefully watched by investors eager for planning security in the energy transition - and is duly exploited by opposition parties wherever possible. In addition, the ‘traffic light’ government continues to feel the crippling effects of the country’s debt brake. A constitutional court ruling at the end of 2023 found that about 60 billion euros earmarked in a Climate and Transformation Fund (CTF) were booked in violation of the limit on new public debt, leading the coalition to hastily find ways to close funding gaps and ensure the continuation of key climate and energy projects.

Far-right AfD benefits from fears of climate action costs - but stumble over self-made scandals

The ruling that is set to reverberate in coming budget debates hit the government at a time when ever more difficult political decisions are needed to counteract climate change and its increasingly obvious effects at the national and the EU level – and when state money will be needed to cushion social impacts resulting from the required measures. Fierce debates over the costs of Germany’s planned heating sector decarbonisation, the phase-out date for combustion engine cars, or ending certain fossil fuel subsidies that resulted in Europe-wide protests by the farming industry are but a few examples of the hurdles towards the goals of climate neutrality by 2045 (and five years later in the EU). A large coalition of nearly 80 civil society groups warned EU leaders in April that a trend towards consolidating budgets in Europe runs counter to what is needed in order to tackle the “unequal distributional effects of climate action” and close ranks in society.

The ascent of far-right and populist parties in Europe, which has been particularly strong for the Alternative for Germany (AfD), in the wake of Europe’s consecutive crises in the past years is fuelled in part by these uncertainties regarding the social impact of climate and energy policy. Many observers expect a strong showing by far-right parties in the elections. Quaritsch’s JDC colleague, Yann Wernert, who focuses on French politics, said the mood in France ahead of the election mirrors that in Germany. “The green wave from 2019 has ebbed away in France, too,” Wernert said. Instead, voters in the EU’s second largest economy are also more concerned with the economic prospects, where climate-related regulation is rather seen as an impediment.

Especially the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) would seek to exploit dissatisfaction, particularly among France’s traditionally powerful agricultural lobby. This has prompted parties that support president Emmanuel Macron to tone down their climate ambitions, even if they continue to support the European Green Deal, Wernert added. “The fear for retaining their industrial core amid the green transformation is what ties Germany and France together most clearly.” And while the rather blunt AfD and the more subtle RN differ in their style and tone, “both parties are very similar regarding climate” and their opposition to progressive policies. German environmental NGO BUND in an analysis of voting patterns pointed out that “MEPs of the AfD systematically vote against the environment and the climate,” making them a clear outlier among Germany’s 14 parties. Major gains for the AfD and its peers could thus lead to “grave consequences” for European environmental policy and the Green Deal, BUND warned.

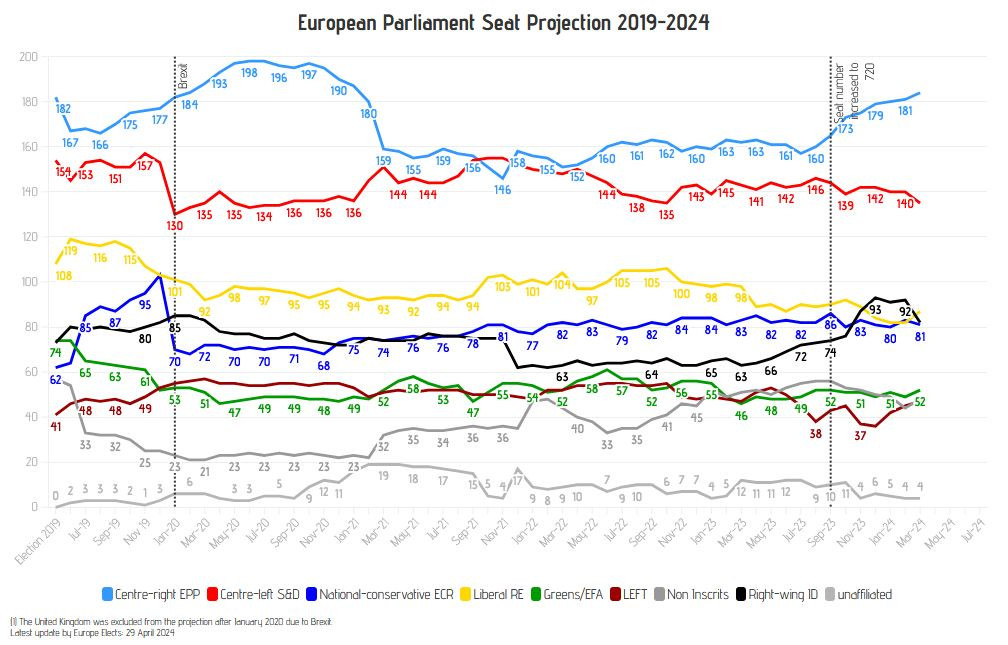

Polls by Europe Elects suggest that the right-wing group “Identity and Democracy,” (ID) which includes the AfD, could become the fourth largest faction in the new European Parliament. However, the AfD’s surge may have reached its peak and reversed in early 2024, following reports about some party members mulling the idea of mass deportations that led to widespread protests across Germany against fascism. Moreover, senior AfD members have made headlines with ties to the Russian and Chinese governments, including an assistant of the far-right party’s top candidate for the EU elections, Maximilian Krah. The party’s constant stream of scandals has begun alienating it from its fellow far-right party RN in France, whose leader Marine Le Pen questioned the collaboration within the European ID group. In a poll on voting intentions for the EU, the party received 15 percent, on par with Scholz’s SPD and behind the Greens (17%) and the CDU/CSU (30%).

The new left-wing populist party Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), founded by former Left Party member Sahra Wagenknecht, could further tip the balance for the AfD at the European elections, the first one in which the BSW is running. Launched only in January 2024, the party polled at about 6 percent for national elections and could receive more than 5 percent in the EU elections. The BSW, which like the AfD holds nationalist views on trade and migration and is critical of Germany’s decarbonisation plans and shift away from Russian energy supplies, is well positioned to lure protest voters away from the far-right party.

German conservatives must balance Green Deal criticism with support for Von der Leyen

While the European far-right has been gaining momentum, the Greens’ fortunes have been reversed since 2019. Riding a wave of climate protests, the Greens in Germany and in Europe celebrated their greatest success so far in EU elections. Five years on, the European Green party group’s prospects are visibly diminished in polls, with a survey by EuropeElects predicting a drop from 74 to 52 seats in parliament if current trends persist. This would mean the Greens lose more seats than the far-right is projected to gain.

Conversely, in Germany, the Greens have been the coalition member that was able to defend its election result of just under 15 percent the best. While the party is polling well-off its pre-2021 election peak, speculation about a Green candidate for the chancellorship in 2025 have begun. Germany’s economy and climate minister Robert Habeck currently appears to be the most promising pick for the party. While the minister has gone through a challenging two and half years amid the energy crisis and the coalition’s decarbonisation push, Habeck continues to be among the most popular members of the government.

The current chancellor’s party SPD, meanwhile, is busy doing damage containment in the run-up to the upcoming election. Not only did his party fail to counter a constant decline in popularity in national polls since Scholz’s surprise victory in late 2021, it also suffered several state election defeats and grapples with the head of government’s weak popularity. In the 2019 EU elections, the SPD already incurred its worst-ever result in a national election, shedding nearly 50 percent of its support to receive just over 15 percent of the vote. Focusing on the threat posed by the far-right, top candidate Katharina Barley hopes to perform better this time, but can expect little help from the SPD’s national performance.

The woes of the chancellor’s party partly are the result of the coalition’s inability to present coherent positions, often stemming from differences between the business-friendly FDP and the other two partners. Yet, the neoliberal party appears to have the biggest cause for concern in the run-up to the June elections. Since scoring over 11 percent in the German federal election in 2021, the party under finance minister Christian Lindner has repeatedly polled below the 5-percent threshold. While this poses no issue for the EU elections, such a result would keep the party out of parliament in the 2025 general elections. The FDP has thus sought to sharpen its own profile within the governing coalition, in which its tax-cutting, deregulation ideas have set it apart from the more left-leaning SPD and the Greens from the outset. With a list of points “for accelerating the economic transition,” including the phase-out of support for renewable power installations and tax reduction across the board, the FDP leadership upset its partners with demands that partly directly run counter to the coalition’s joint policy positions.

“The FDP seems to regard the election campaign as an opportunity for readjusting its position within the coalition,” researcher Quaritsch commented. Fittingly, more than one third of voters (34%) in a poll said they believe the FDP is causing the most trouble, whereas about a quarter (25%) said the Greens are to blame. Only six percent saw the SPD as a factor for destabilising the government.

At the same time, some voters might choose to use the election as a “reckoning” for Scholz’s government, the JDC researcher added. The conservative CDU/CSU alliance can hope to reap the fruits of the ‘traffic light’ coalition’s constant infighting and emerge as the clear leader in the election, after its defeat in the latest national vote. Yet, Germany’s conservatives face their very own conundrum ahead of the election: How to oppose national and European climate policies seen as an obstacle to industrial recovery while not undermining their own top candidate, European Commission leader Ursula von der Leyen?

Von der Leyen championed the European Green Deal as her commission’s key instrument for reconciling economic recovery, greater energy security and climate neutrality by 2050. However, the commission leader is not known as a close ally of her party’s current head, Friedrich Merz. JDC researcher Quaritsch said the farmers’ protests against Green Deal regulation had diminished von der Leyen’s standing within her own party. “She will have accepted demands for lowering her green priorities and reduced regulation to secure her nomination” within the CDU, Quaritsch argued.

Curbing von der Leyen’s push for ambitious emissions reduction under the Green Deal thus emerged as a focal point in the CDU’s preparation for the EU elections. Egged on by criticism from industry groups and the farmers’ protests, many conservatives argue that a fast recovery of economic output through low energy prices and reduced regulation have become more important than greater ambition in environmental matters. The CDU/CSU alliance as well as the centre-right European party group EPP have thus called for reversing the planned phase-out of combustion engines and blocked proceedings for the EU’s Nature Restoration Law – a trend that could ultimately come back to haunt the conservatives’ top candidate. “Things shouldn’t tilt over in the other direction now,” a spokesperson for von der Leyen said in a news report earlier this year.