Understanding the European Union’s Emissions Trading Systems (EU ETS)

Content:

- What is the EU ETS?

- How does the EU ETS work?

- What is the emissions reduction target in the EU ETS?

- What is new with the 2023 EU ETS I reform?

- What is the new trading system for transport and buildings sector, the ETS II?

- How must the ETS develop in the future?

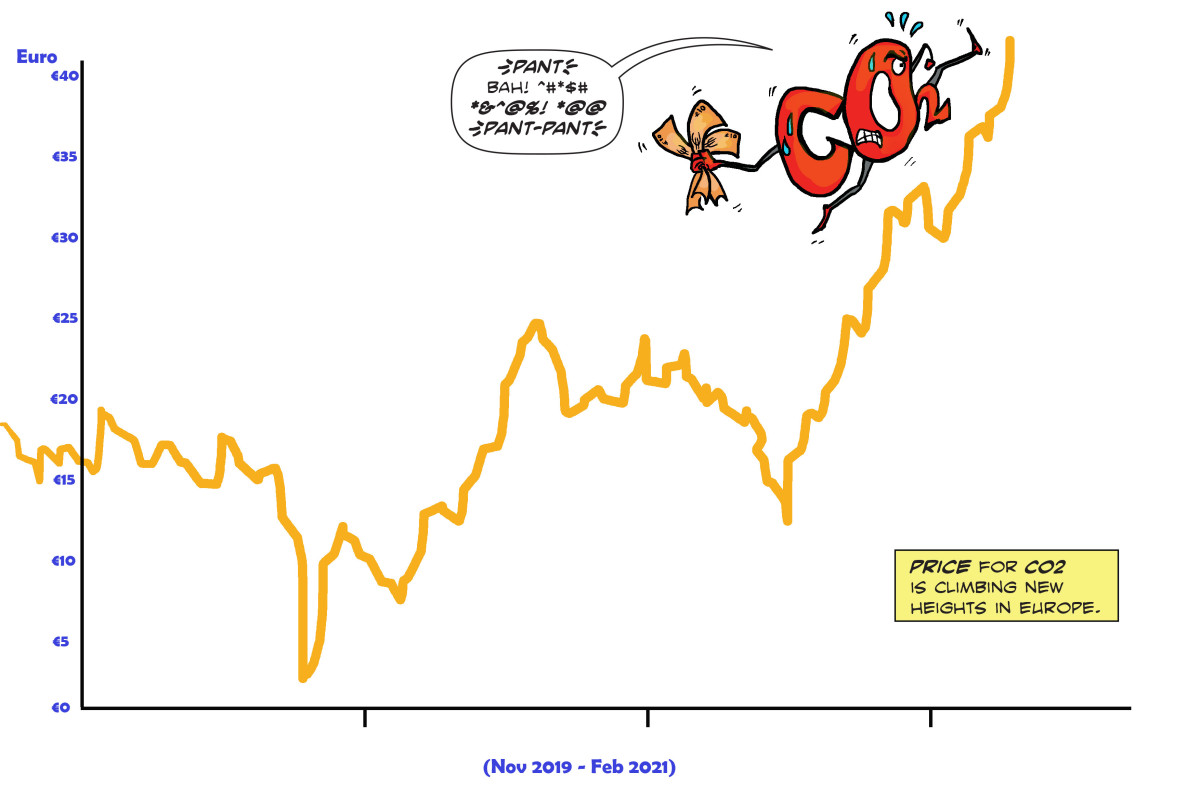

- How has the ETS price developed over the years?

Note: This factsheet differentiates between the original emissions trading system for the energy and industry sectors ("EU ETS I"), and the new system for transport and buildings ("EU ETS II").

What is the EU ETS?

With the EU ETS, the European Union has created a market mechanism that gives CO2 a price and creates incentives to reduce emissions in the most cost-effective manner. It is a cornerstone of EU climate policy. The objective of the original ETS I is to bring down emissions in power generation and energy-intensive industries (such as the production of iron, aluminium, cement, glass, cardboard, acids, etc) by a certain percentage each year. Extending current rules (in place for the period until 2030) would mean that the cap reaches zero by 2039, but further future reforms will likely change this.

The system has helped reduce emissions from these sectors by about 47 percent between 2005 and 2023. Data for 2023 shows a record reduction of 15.5 percent, compared to 2022 levels, largely due to a boost in renewable energy. The EU ETS is the oldest and by far the largest of 36 carbon trading systems in operation around the world by early 2024, which together cover 18 percent of global emissions, according to the 2024 status report by the International Carbon Action Partnership.

From 2027, a new emissions trading system will cover fuel distribution for road transport and buildings, and additional industrial sectors. ETS II will first run in parallel to the original system, but there are plans to merge the two in the early 2030s.

[Several NGOs have published a Beginner's Guide to the EU Emissions Trading System: EU ETS 101]

Companies must buy or receive allowances corresponding to their CO2 emissions, making power production from burning coal and other fossil fuels more expensive, and clean power sources more attractive.

The EU ETS follows a ‘cap-and-trade’ approach: the EU sets a cap on how much CO2 can be emitted – which decreases each year – and companies need to have a European Emission Allowance (EUA) for every tonne of CO2 they emit within one calendar year. They buy these permits or receive them for free (more on free allocation below) and are able to trade them. After each year, the companies surrender enough allowances to cover their full emissions.

The EU ETS covers CO2 emissions from power stations, energy-intensive heavy and civil aviation. Flights from outside the EU or to airports outside the union are not included in the system’s scope; only those between and within countries in the European Economic Area must comply with the programme. From this year onwards, the system will also cover emissions from maritime transport.

Heavy industry receives a certain amount of free emissions allowances to help compete with businesses outside the EU which are subject to less stringent climate legislation.

Companies face a fine if they emit more CO2 than they have covered by emission allowances. The fine is 100 euros per excess tonne. Companies are therefore incentivised to reduce emissions by investing in energy efficiency as they can then sell excess allowances. (For context: the world’s largest chemical company, Germany’s BASF, produced 20.2 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents in 2021 scope 1 and 2 emissions).

The revenues of the EU ETS mainly go to member states' budgets, or flow into the EU-wide Innovation Fund and the Modernisation Fund. In 2022, the EU ETS generated a total of 38.8 billion euros in auction revenue, 7.7 billion euros more than in 2021. Of this amount, 29.7 billion euros was distributed directly to member states. Germany had revenues of 7.8 billion euros.

The system covers around 9,000 power plants and factories in the 27 EU member states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, encompassing around 36 percent of the EU’s total greenhouse gas emissions (2022).

The objective of the EU ETS is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power stations and other energy intensive industries by a certain percentage every year (linear reduction factor – LRF). As of 2013, the LRF was set at 1.74 percent to achieve an overall reduction in these sectors of 21 percent by 2020, compared to 2005 levels. Between 2021 and 2030 the overall number of emission allowances was initially set to decline at an annual rate of 2.2 percent. The reduction factor was set in 2018 to align with the previous EU targets of cutting all greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40 percent by 2030 compared with 1990 levels.

However, the reform in 2023 (see below) of the ongoing phase 4 of the ETS (2021-2030) introduced more ambitious targets: Overall emissions will be reduced by 62 percent by 2030, compared to 2005. The LRF will be raised to 4.3 percent for 2024-2027 and then to 4.4 percent from 2028.

This trajectory would bring the cap to zero by 2039 (this does not account for small batches of allowances for the aviation and maritime sectors). Once the EU decides on a climate target for 2040, it will also set out to further adjust the ETS.

In mid-2021, the European climate law came into force. This sets a binding target of a net greenhouse gas emissions reduction (emissions after deduction of removals) by at least 55 percent by 2030 compared to 1990. In order to achieve this new, more ambitious, goal the European Commission presented its “Fit for 55” package of new rules and legislative proposals in July 2021 – including a renewal of the EU ETS. After negotiations, the European Parliament, member state governments in the EU Council, and the Commission reached a deal in December 2022 to reform the existing ETS, and introduce a second system for transport and heating fuels (see below). The final acts were signed in 2023.

The key changes are:

- New 2030 target for ETS emissions is -62 percent (previously -43%) compared to 2005

- New linear reduction factor: 4.3 percent from 2024 to 2027 and 4.4 percent from 2028 to 2030

- Member States should spend the entirety of their emissions trading revenues on climate-related activities

- Shipping emissions are to be included within the scope of the EU ETS. While the emissions for ships arriving from outside the EU or departing to a port outside the union will only be covered by half, any emissions from inner-EU maritime transport are fully covered under the ETS. The EU agreed on a gradual introduction of obligations for shipping companies to surrender allowances: 40 percent for verified emissions from 2024, 70 percent for 2025, and 100 percent from 2026. For now, only big offshore vessels of 5,000 gross tonnes and above will be included

- Free allocation and interaction with CBAM: The rules for companies receiving free emission allowances will change, phasing these out step by step for products that fall under the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) by 2034, for example cement, steel and fertilisers (2026: 2.5%, 2027: 5%, 2028: 10%, 2029: 22.5%, 2030: 48.5%, 2031: 61%, 2032: 73.5%, 2033: 86%, 2034: 100%). From 2026, free allocation of emission allowances should be conditional on investments in techniques to increase energy efficiency and reduce emissions.

- Aviation: The EU ETS applies for intra-European flights: EU institutions agreed to phase-out free allocation to aircraft operators and to move to full auctioning of allowances by 2026 to create a stronger price signal. In addition, the so-called non-CO2 effects of aviation will be included in the ETS I from 2025, initially through monitoring and later probably also with the obligation to surrender allowances. To deal with extra-European flights to and from third countries, the global Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) will be integrated into the ETS

- Emissions from burning waste are to be monitored from 2024, and likely included in the ETS from 2028 (member states can push this to 2030)

- Market stability reserve reform: 24 percent of all ETS allowances will continue to be placed in the market stability reserve. This mechanism is intended to reduce the historical surplus of allowances and, on the other hand, enables the EU ETS 1 to react more flexibly to future supply and demand shocks. Based on the total number of allowances in circulation, the mechanism removes allowances from the market or distributes them by adjusting the auction volumes in subsequent years

More information: The German Environment Agency published a report about the reform, and the European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST) has explained the changes in its 2023 State of the EU ETS Report.

As part of the Fit for 55 reforms, the EU decided on the EU ETS II: a new emissions trading system to cover fuel distribution for road transport and buildings, and additional industrial sectors. So far, emission reductions in those sectors have been insufficient to put the EU on a firm path towards its 2050 climate neutrality goal, said the Commission. The system will run separately from the existing EU ETS.

The ETS II:

- Fully operational by 2027 (monitoring and reporting of emissions already in 2025)

- Could be postponed until 2028 if oil and gas prices are exceptionally high (details in directive, article 30k)

- Covers fuels used for combustion in the buildings and road transport sectors as well as in additional sectors which correspond to industrial activities not covered by the ETS I

- Cap and trade system like the ETS I, but covers emissions upstream: Will apply to distributors that supply fuels (not households or drivers)

- Those suppliers must "surrender allowances for their verified emissions corresponding to the quantities of fuels they have released for consumption"

- Target: Reduce emissions by 42 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels

- No free allowances: Everything is auctioned "as buildings and road transport sectors are under relatively little or non-existent competitive pressure from outside the union and are not exposed to a risk of carbon leakage"

- Member states can exempt suppliers until 2030 if there is a national CO2 price which is equivalent or higher than the new ETS II price

- Revenue use:

- Member states must use revenues for climate action and social measures

- Part of revenues will be used for EU Social Climate Fund to support vulnerable households and micro-enterprises

- Includes a price stability mechanism: If the price of an allowance in ETS II rises above 45 euros during the first three years, additional allowances can be released

In Germany, where a similar carbon pricing system for transport and heating fuels already exists, researchers have warned of possible jumps in prices when the EU system comes fully into force. As the allowances are traded in the market, it is unclear how high the price per tonne of CO2 is going to be in the ETS II.

The ETS has been reformed several times to cover new trading periods, include additional sectors, tackle unintended price developments, and generally adapt to new circumstances. Future developments include looking at the period post-2030; and the European Commission is also set to examine how negative emissions could be covered by emissions trading in a report to be published by mid-2026. Researchers have said that fundamental aspects of any future ETS reform must be tackled as soon as possible to avoid unintended price developments, provide planning security for businesses, and ensure that the transition progresses as intended.

With the current trajectory for the cap to reach zero in 2039, it is unclear how the market would react as "the functioning of an ETS approaching a final zero-supply state largely remains uncharted territory”, Michael Pahle of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and several colleagues wrote in a 2024 paper.

In an op-ed in Tagesspiegel Background, Pahle also said that the possible future integration of carbon removals in the ETS would fundamentally change the system. He also warned that governments might choose to water down the emissions cap if prices were to rise too much. "This in turn would be a considerable blow to the credibility of the climate targets," he said.

Think tank European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST) has said that European emissions trading is entering "a new phase, with industry decarbonisation taking centre-stage" and net zero emissions by 2050 as the key target. ETS reforms must be kickstarted soon because "time is not on our side, if looked upon from the point of view of an investment cycle”, it said. In its ETS status report 2024, the think tank said that present trends indicate that the industrial sectors under the EU ETS will face significant challenges to meet an ambitious 2040 target of a 90-percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, should this target be decided.

The think tank has discussed the possibility of establishing an EU Carbon Central Bank as an institution to supervise and manage the constantly evolving market. Such a bank could help manage the "disruptive moment, and the period leading to it" when allowances run out at the end of the 2030s, and "ensure price stability in strategic market for EU industrial production”, said ERCST. It could also manage the integration of carbon removals in the ETS.

In the first two trading periods of the EU ETS (2005-2007 and 2008-2012), most allowances were given out in large amounts for free, pushing the price for first-period allowances to zero in 2007.

In its third phase (2013-2020), 40 percent of allowances were auctioned, pushing electricity producers to buy all their allowances (with exceptions in some member states like Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, etc). From 2021, around 57 percent of the union-wide cap is auctioned, and only Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania decided to continue allocating free allowances to the energy sector.

Still, free allocation prevailed in manufacturing and aviation, and sectors deemed to be at risk of ‘carbon leakage’ also received an extra amount of free allowances. As a consequence of the generous distribution of free emissions allowances, prices for permits were never as high as envisaged. The surplus of permits grew even greater after the 2008 economic crisis caused emissions to fall faster than anticipated (production in the steel industry alone declined by 28 percent between 2008 and 2009). The price fell from 30 euros per allowance in 2008 to 2.75 euros in 2013.

During the system’s 2018 reform, a reduction in the number of permits distributed for free was agreed upon. As part of this reform, in the programme’s fourth phase (2021-2030), the number of economic sectors deemed to be at risk of carbon leakage, and thus entitled to free emissions allowances, were cut. With the agreements on reforms of the system, permit prices rose considerably, from 9.68 euros in 2018 to a record of 100 euros in early 2023.

However, the price fell again to about 60 euros by early 2024 due to several reasons. Reduced gas prices mean that electricity is produced with lower emissions, and shrinking energy demand from industry pushes down the need for allowances in the sector, said Hæge Fjellheim, of carbon market intelligence company Veyt. In addition, the EU accelerated the energy transition and reduced dependence on Russian fossil fuels through its REPowerEU plan. One element of this plan is to finance measures by selling ETS allowances earlier than planned ("frontloading"), which results in more allowance supply in the years 2023-2026. This also has a price-dampening effect in those years. Eventually, prices will rise again, wrote Veyt, forecasting 130 euros per allowance in 2030. Other analysts also see prices rise in the coming years, albeit slower than initially forecast.