Public discontent with government risks slowing Germany’s climate efforts

After almost two years of crisis management during the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, Germany’s government coalition is faced with the complicated reality of making tough climate policy decisions as its term nears the halfway point this autumn.

In light of a weakening economy, low approval ratings and surging poll numbers for the far-right populist Alternative for Germany (AfD), the government is struggling to actualise its own aspirations: modernising and making climate-neutral the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2045. Or “Getting the necessary innovations off the ground to secure Germany’s prosperity and role in the world, and stop man-made climate change at the same time,” as chancellor Olaf Scholz put it in his summer press conference. He reassured journalists that the coalition of Social Democrats (SPD), Green Party and Free Democrats (FDP) had “not forgotten this task”, despite the crisis-laden first half of the legislative term.

The government must now get its act together and show the same vigour it did during the pandemic or in its response to the war against Ukraine.

“Germany is in the middle of the transformation to climate neutrality and has great support for this process from the population,” says Dirk Messner, one of the country’s leading voices on sustainable development and climate action, and president of the German Environment Agency (UBA).

Messner told Clean Energy Wire the governing coalition had presented “a quite ambitious energy and climate protection programme” at the beginning of its term, but “must now get its act together and show the same vigour it did during the pandemic or in its response to the war against Ukraine.”

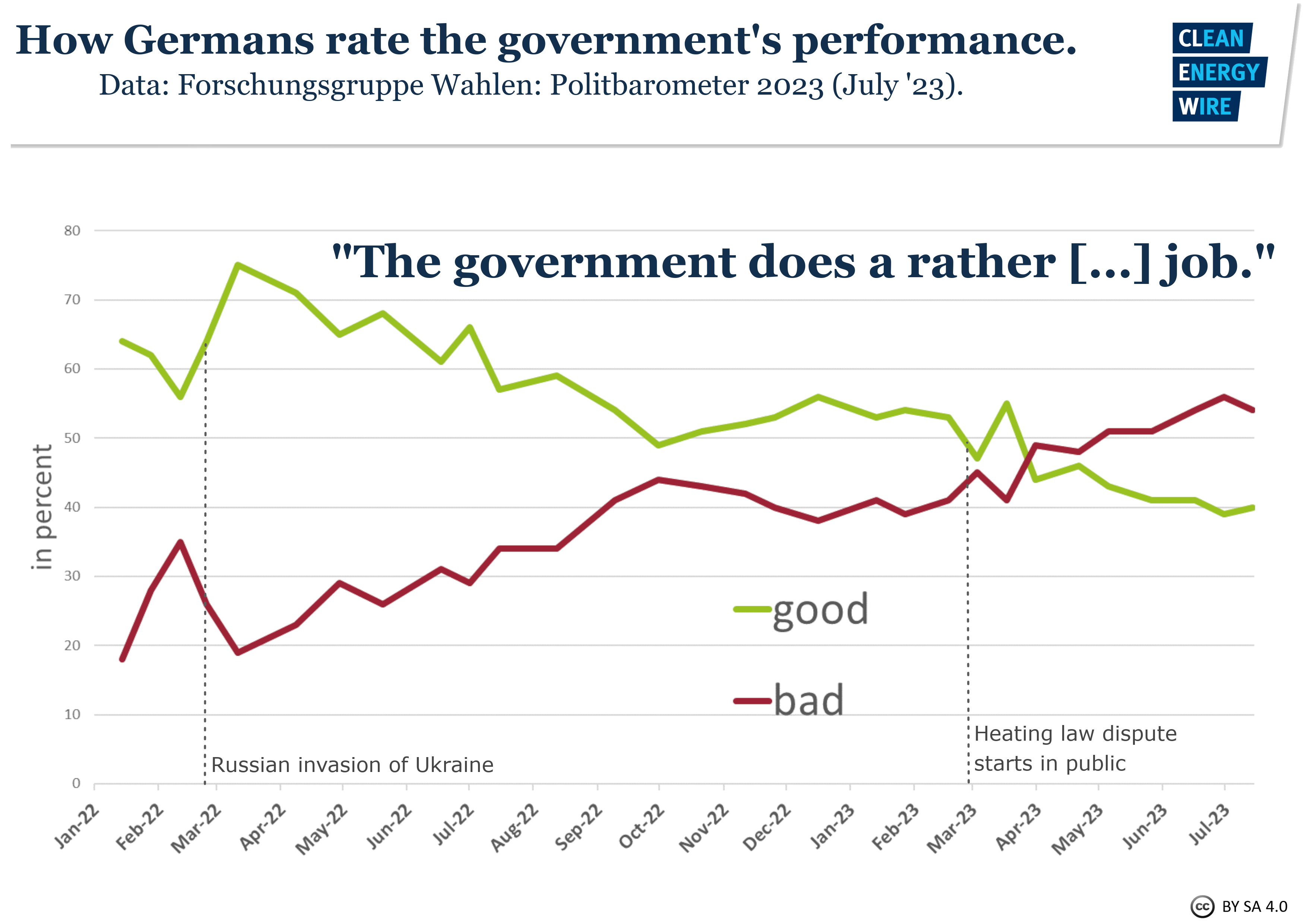

Energy and climate policy has likely never played a bigger role for a government in Germany, and, in summer 2023, it is marked by contrast between acceleration and stumbling blocks: the government introduced a raft of law reforms to speed up renewables expansion and support industry’s move to climate neutrality. The country’s solar sector is recovering with steadily increasing new installations, while oil majors BP and Total Energies pledged to pay billions of euros for the right to build offshore wind farms in the North and Baltic seas – joining other global businesses’ major clean tech investment announcements for Germany. At the same time, public appetite for specific policy measures has soured as energy prices reached record highs during the energy crisis. This is only worsening as the effect of climate measures on people’s lives is increasingly felt, and while the coalition has struggled to agree on key climate measures like the phase out of fossil fuel heating, the reform of the climate law or proposals to reduce transport emissions.

“The government is apparently entering a third phase after the coronavirus pandemic and the war [in Ukraine],” political scientist Karl-Rudolf Korte told public broadcaster Deutschlandfunk (Dlf) in an interview. This being “its ‘modernisation’ or ‘progress’ project.” The three-party alliance would finally be able to put focus on implementing its 2021 coalition agreement, in which it had promised to “dare for more progress” and modernise the economy to future-proof the country.

After the period of multiple crises, in which the government still enjoyed fairly generous approval ratings, government policy-making on issues like migration or fossil fuel heating phase-out in German homes “is much more immediately polarising,” said Korte.

A recent report by the Mercator Forum Migration and Democracy (MIDEM) at Technische Universität Dresden (TUD) showed that climate policies are among the most polarising topics in many European countries, Germany included. On these issues, people show the greatest hostility towards those with opinions differing from their own.

That makes the governmental energy transition and climate policy especially prone to divisive public debates such as what erupted over heating legislation.

A public row between the coalition parties over the proposed legislation to phase out fossil fuel-powered boilers sparked a fierce national debate about the decarbonisation of the heating sector in the first half of this year, fuelled by attacks on the plans from the country’s largest tabloid Bild and other conservative and right-wing media outlets. Critics argued that the investment costs for climate-friendly solutions like heat pumps would overburden homeowners and tenants.

Commentators saw the Greens as an isolated party, even with in the government coalition. The partners SPD and FDP, together with the opposition had tried to profit at the expense of economy and climate minister Habeck, criticising his ministry’s plans as anti-business, anti-freedom, or anti-social, wrote Georg Löwisch in an opinion for public broadcaster Deutschlandfunk.

Graph shows survey results to question](/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/forschungsgruppewahlen-trend-important-issues-survey-germany_2.png?itok=0CRtb1gv)

In the end, the coalition government reached a hard-fought compromise by increasing subsidies and effectively postponing a broad ban on new fossil fuel heating systems.

The controversy has left parts of the population confused about the direction of travel, dissatisfied with how climate policy is being implemented, and sometimes even estranged from established politics. Demand for heat pumps has subsequently collapsed.

The recent news that the German public's support for the climate movement has halved, following the rise of controversial street blockades by more radical climate activists, has raised concern that such protests could actually harm the cause and lead parts of the population to oppose climate action in general. However, surveys continually show that the need for climate action is undisputed amongst a large majority of Germany’s population – even as other worries like the pandemic and the energy crisis came took precedence. Most parties share a consensus about the general targets. Germany’s previous conservative CDU/CSU alliance and Social Democrat government coalition introduced the country’s first climate law in 2019, which stipulated the target of climate neutrality by 2050, which was later pulled forward to 2045. Economy minister Robert Habeck called it “an abstract legal framework that was easy to agree upon,” but argued that the more difficult task was deciding how to meet the goal.

A survey by German tabloid Bild – a paper which has attacked the government’s energy and climate policy for months – showed that 76 percent of Germans are worried about their future due to climate change, with 46 percent saying that the government is acting too slowly on climate. By contrast, 25 percent said the government was acting an appropriate pace, and 19 percent said it was acting too quickly.

The annual Social Sustainability Barometer survey, conducted by the Helmholtz Centre Potsdam (RIFS) just as the heating law controversy emerged in early March, found that, while support for climate action remained high, many people were dissatisfied with the political implementation of the energy (53%) and transport transitions (38%). At the same time, the survey found that Germans generally underestimate fellow citizens’ support for climate action, such as tolerance for building wind turbines near their homes. This may give policymakers the false impression that there is not enough support to implement the necessary measures, the researchers warned.

Other surveys paint an even bleaker picture of government performance. Market research firm the Rheingold Institute conducted a survey on “the German state of mind in summer 2023”, commissioned by the Identity Foundation. Paul Kohtes, head of the foundation, said the findings could be described as “dramatic” and showed “a deep resignation towards politics and our future possibilities.” Eighty-six percent of respondents agreed with the statement that “politicians must develop overarching solutions to all the existing challenges“, such as the climate crisis, inflation, social inequality, because these crises cannot be dealt individual citizens. However, three quarters (73%) agreed “our politicians have no idea of what they are doing,” with only 34 percent saying they trust the government and its policies.

It will be difficult for the government coalition to regain the trust lost amongst the public disputes and the mishandling of heating law negotiations. Still, the 2022 Environmental Awareness Study, which the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) published in early August this year, showed that even before the recent controversy, citizens are worried about climate action policies. While the vast majority (91%) of Germans support a climate and environmentally-friendly economic transformation, two in five worry that it could lead to social injustice and threaten their own status. This was an “alarming number,” which could be seen by the government as a call to action, UBA head Messner said.

“The government has to design policies in a socially just way,” he told Clean Energy Wire. “This is very important for the people. Although they support the transformation, they are afraid that it might harm their socio-economic standing.”

Messner warned that the coalition must finally get serious about implementing the “climate bonus” (Klimageld) it has promised to help cushion the effects of rising CO2 prices, particularly for lower-income households. With this annual per-capita payment – the same for each person – the state would redistribute carbon pricing revenues, but the introduction has been delayed. In light of EU plans to introduce emissions trading for fuels used in transport and buildings from 2028 (ETS II), “this has to come now,” Messner said.

By the summer 2023, the Green Party had dropped to its lowest level in some polls in five years (13%), while the far-right populist AfD has surged to an all-time high of little over 20 percent. The party rejects the scientific consensus on climate change, claiming that climate action only leads to high energy prices and a loss of industry, jobs and prosperity. In a draft for its 2024 election programme, the party calls the “ban” of oil and gas heaters a “severe encroachment on the property and fundamental rights of citizens.”

A poll by infratest dimap showed that most people who said they would currently vote for the AfD would do so because they are disappointed by the other parties (67%), while only a third was truly convinced by the AfD (32%). "The constant squabbling between the ruling parties is causing people to lose orientation and trust in the government,” the pollster’s Stefan Merz told Politico. Migration topped the list of topics which influenced people’s choice to support the AfD, with 65 percent saying it played an important part. Energy, environment and climate policy came in a distant second (47%).

UBA’s Messner called on the country’s parties to realign the debate: “We have to return to a situation where politicians make clear that the entire democratic spectrum – which in our country is over 80 percent – is arguing about the right climate action instruments, but not about the goal of climate policies.”

The biggest opposition party in parliament, former chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance, has meanwhile not benefitted from the decreasing support for the government. The party has failed thus far to portray itself as the alternative to the ruling coalition, and CDU leader Friedrich Merz faces competition within his party, while coming under fire for an interview in which he suggested he was open to working with the AfD in local governments.

Chancellor Scholz has attributed the rise of the far right to the worries people are feeling about their future “in 10, 20 and 30 years”, arguing that the coalition’s transition policies are necessary to reassure citizens that “it will turn out well for each and every one of us.” Scholz said that he was confident the AfD would “not do much differently” in the next federal election than in the 2021 vote (it received 10.3% in 2021).

During the heating law dispute, economy minister Habeck said that he misjudged the change in public mood over the winter 2022/2023. In the throes of the energy crisis, despite high prices, citizens largely supported the fast-tracked, often large legislative changes on energy policy, from speeding up renewables expansion to building up a domestic import infrastructure for liquefied natural gas (LNG). However, as the country managed to avoid a severe gas shortage – also helped by a mild winter – this changed.

“We continued our 2022 working mentality for too long,” Habeck said in a German talk show. “We got through the winter all right,” and with all that Germans had to go through before – such as the war in Ukraine and high prices – “the [heating] legislation in the spring was the straw that broke the camel's back.”

In an editorial for Euractiv about developments labelled as ‘Wende’ (turning points) – from the ‘Zeitenwende’ of Russia’s war against Ukraine to the ‘Energiewende’ to push fossil fuels and nuclear out of the energy mix – journalist Nikolaus Kurmayer warned that this “dangerous obsession” with the term ‘Wende’ could alienate many citizens who are wary of such sharp policy turns. “Appetite for change is at an all-time low,” he wrote.

During the talk show interview, Habeck argued that majorities in society are necessary to implement climate action, adding that such a majority had been missing with the leaked early draft of the heating law. “If people don't want it, climate protection will be voted out,” he added.

This could happen as soon as October. Elections in major German states Bavaria and Hesse will kick off a twelve-month election cycle which will show whether the AfD is able to turn high poll numbers into election results. Populists and the extreme right have a track record of capitalising on people’s fears in election campaigns, and in addition to migration, the AfD has long since started to weaponise climate policy.

Polls indicate that Bavarian state premier Markus Söder, from the conservative Christian Social Union (CSU), will be able to renew the current coalition with the centre-right Free Voters, while the AfD is polling at similar levels as its last election result. Söder has said that his party, together with the conservative CDU would “completely overhaul and also abolish” the heating law after the next federal election. In Hesse, the AfD also remains at the poll level seen in the last state election in 2018.

However, in June 2024, voters in Germany, alongside other EU citizens, will head to the polls to elect a new European Parliament. A recent poll by INSA puts the AfD in second place after the conservative CDU/CSU alliance.

The real test awaits in September 2024, when three eastern states Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg will go to the polls, where the far-right has traditionally been strong. While a lot can happen in a year, the AfD is currently leading in the polls in all three states.

In any case, looming elections “will have a major influence on the work of the government,” said political scientist Korte, taking to the scheduled heating law as an example. “The effort to agree on the heating law before the summer recess was done with the aim to avoid disquiet ahead of the elections” in Bavaria and Hesse. This attempt failed after Germany’s top court blocked the law’s rapid passage through parliament. The vote is now planned for after the summer recess – certain to revive the debate just weeks before the elections.

With all the public controversy over the heating law and staff in the economy ministry, and the “miserable” state of cooperation within the ruling coalition, and low public approval ratings, it is also worth looking at what the government has actually achieved on energy and climate policy-making.

“The traffic light's track record is better than its public perception,” writes Michael Schlieben in an opinion piece for Zeit Online.

First, the coalition manoeuvred through the energy crisis. Just months after Scholz took office, Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, pushing the chancellor to declare a “Zeitenwende” (turn of an era) which mostly upended the government’s plan to steadily work through its energy and climate agenda. Instead, the coalition needed to deal with high energy prices, the threat of severe gas shortages, and a looming recession. Politicians worried about the threat of popular protests or even social unrest, warning that solidarity among citizens could be pushed to the limit with a hard, cold winter.

However, over the course of 2022, the government managed to secure enough alternative gas supply, partially through the rapid build-up of domestic import infrastructure for liquefied natural gas (LNG). It also introduced emergency legislation in record time, and presented several relief packages for citizens and businesses. Germany thus managed to avoid a harsh economic downturn, and the feared “winter of discontent” did not materialise. Mild temperatures certainly helped too, as demand for gas to heat homes was reduced.

In his summer press conference, chancellor Scholz emphasised the opportunity the crisis presented to transition away from fossil fuels for the sake of domestic energy security. “The need to act very quickly to avoid a cold winter and a long-lasting economic crisis […] has also considerably accelerated the pace of [the climate-friendly modernisation] and, as I perceived it, also increased the consensus that this must now be done at great speed,” Scholz told journalists in the room, speaking of his coalitions achievement in meeting the moment with the necessary speed.

The list of climate and energy policies presented by the government and decided by parliament since the coalition took office is long. The reforms form part of the comprehensive climate action programme meant to get the country back on track to reaching climate targets, of which the economy ministry presented a draft in early summer, after months of delay.

The coalition raised renewables expansion targets, aiming to double onshore wind and more than triple solar PV and offshore wind power capacity from today’s levels to ensure renewable energy covers at least 80 percent of electricity consumption by 2030. It introduced legislation to ensure sufficient land is available for renewable expansion and to speed up planning and permitting procedures for these facilities and the necessary power lines. It abolished the renewables surcharge to finance renewables expansion from the federal budget, and launched a pioneering subsidy system to support industry in slashing emissions. Yet, the controversial heating law and the – also disputed – climate law reform, are yet to be agreed upon, which is likely to happen after the summer recess.

“The pace has picked up in our country, and it will be accelerating more and more,” Scholz added.

Pace is needed, as there are still many things on the government’s agenda until the next national election in 2025. This includes a planned Carbon Management Strategy which would illuminate Germany’s plan to tackle carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the coming decades; rules on future hydrogen imports; or the promised climate bonus. The government also aims to recalibrate the electricity market design, assess the coal exit with the possibility of pulling it forward to 2030, and present a climate foreign policy strategy. There are also unresolved areas within the coalition, such as Habeck’s proposal for an industry power price which both chancellor Scholz and finance minister Lindner view with some apprehension.

In his summer press conference, Scholz said his impression was that his coalition still had a lot to do as the summer recess dawned. Results, he added, would be achieved with “more speed and less noise” than until now.