Growing energy cooperation between EU and UK defies worst of Brexit fallout

Energy issues have been at the centre of discussions ever since debates about the potential effects of Brexit started. Six years after the narrow British vote to end its EU membership, and over two and a half years since the UK’s official departure from the bloc, joint energy strategies are considered crucial by both regions – not least because Russia’s war on Ukraine and its effects on energy markets illustrate what is at stake. However, this does not mean the countries’ energy ties have not become more complicated since the UK’s exit.

“It is a different relationship. It’s now underpinned by different rules”, energy and transport officer Sara Lines from the British Embassy told CLEW.

North Sea is shared focus of UK’s and EU’s renewable power ambitions

Operating under different rules has not pulled the plug on several initiatives that aim at intensifying collaboration on shared energy infrastructure of the UK and the rest of Europe. The UK’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) works with its neighbours within the North Seas Energy Cooperation, a forum that promotes renewable energy growth, and “is very keen” to continue doing so, Lines said. A forthcoming memorandum of understanding will need to be signed by the European Commission, in order to redefine the UK’s position in this forum as a non-EU member, they explained.

The department’s enthusiasm for sustaining cooperation is shared on the continent. German Energy Agency dena told CLEW that it would be “absolutely” beneficial to both regions to have more power links. “The better the systems are interconnected, the more each country can ramp up renewables, and then export (the renewable energy) when they have more than they need, or import” in the opposite scenario, Philipp Heilmaier from dena said. Andreas Jahn of energy regulation NGO RAP agreed that maintaining solid ties with the UK’s energy market would be in the EU’s own best interest. “Every single interconnection capacity helps to lower balancing costs and will decarb the power system in the long run”, Jahn told CLEW.

Moreover, the British government remains tied to climate obligations similar to the EU’s also after withdrawing from joint mechanisms. One major impact of Brexit was the UK leaving the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), Simon Evans of UK-based news outlet Carbon Brief told CLEW. This meant the country was no longer legally bound to EU emissions targets. However, the UK has its own long-standing legal obligations of reducing emissions by 68 percent by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, which remain unaffected by its exit from the union. “In fact the UK’s own targets from the 2008 Climate Change Act were always more ambitious than the UK’s Effort Share targets under the EU’s regulation”, Evans noted. This meant that the UK was not able to roll back on any emission-reduction efforts post-Brexit.

UK has “scope” for helping to cover EU’s skyrocketing LNG demand

Russia’s war against Ukraine has resulted in rapidly rising gas prices, which in turn catalysed concerns of energy security across the European continent. In response to the war, the UK, Germany and many other EU countries announced plans to commit to a rapid phase-out of Russian fossil fuels. The embassy said that the UK regards it “absolutely critical that we work with international partners to maintain stable energy markets and prices,” a position mirrored by German chancellor Olaf Scholz’s calls for Europe-wide solidarity in light of Russia’s aggression.

There is also “scope for the UK to import LNG into the continent”, Lines said, which could help secure European gas supplies and reduce dependency on Russia. Despite speculation of the UK cutting energy exports in aid of prioritising its own needs, the embassy said that this would be very unlikely to occur unless an emergency scenario evolved. “This just wouldn’t be in anybody’s interest”, Lines said.

Germany, meanwhile, has made plans with countries across Europe and beyond during the past few months to intensify energy cooperation on LNG and also green hydrogen, including Austria, Norway, and Qatar, as it faces the possibility of gas shortages due to cuts in Russian supplies.

Beyond immediate responses to the energy crisis, the UK both retains and aims to increase cooperation with the EU, especially Germany, despite Brexit. Plans of building further interconnectors and supporting each other by means of renewable energy exports are already underway, and Russia’s war could accelerate cooperation even further within the next decade.

UK plans to become ‘Saudi Arabia’ of wind power key incentive for further interconnectors

Both Germany and the UK are leading countries in the way of offshore wind power and already in 2019 announced plans to boost cooperation in the key renewable power technology despite the "windy political environment" prevailing between the two regions back then as much as today. More recently, the first UK-Germany interconnector, Neu Connect, had its funding approved at the end of July 2022 , enabling construction to start a few months later. The power link will be used to transfer excess renewable energy generated from offshore turbines between the two countries.

According to the embassy in Berlin, the UK “plans to increase our interconnection with neighbouring countries”, with an “ambition of an 18 gigawatt interconnection by 2030, which is a three-fold increase on 2020 levels”. The planned hybrid (also known as multi-purpose) energy trading links would prevent the need for curtailing of wind power in the case of excess production, which has previously often been the case in northern Germany, where large wind power output can exceed the grid’s capacity for absorbing it. Once electricity has been generated, for example by offshore wind farms, it cannot yet be stored adequately and so is wasted if it cannot be utilised. With its planned continual expansion of offshore wind power, the UK anticipates that it too could run into the need for curtailing if there are insufficient means to export the excess energy, Carbon Brief’s Simon Evans said.

In 2020, UK prime minister Boris Johnson raised ambition by speaking of the country’s ability to become a ‘Saudi Arabia of wind power’. Although living up to the comparison still leaves a lot of work to be done, the general aspiration is in line with the country’s Energy Security Strategy published in April, where the UK set out its ambition of delivering up to 50 GW electricity from offshore wind by 2030. This much wind power is unlikely to be fully utilised by the UK alone, making plans of interconnectors more important than ever.

Green Hydrogen potential can be unlocked from anticipated excess renewable energy

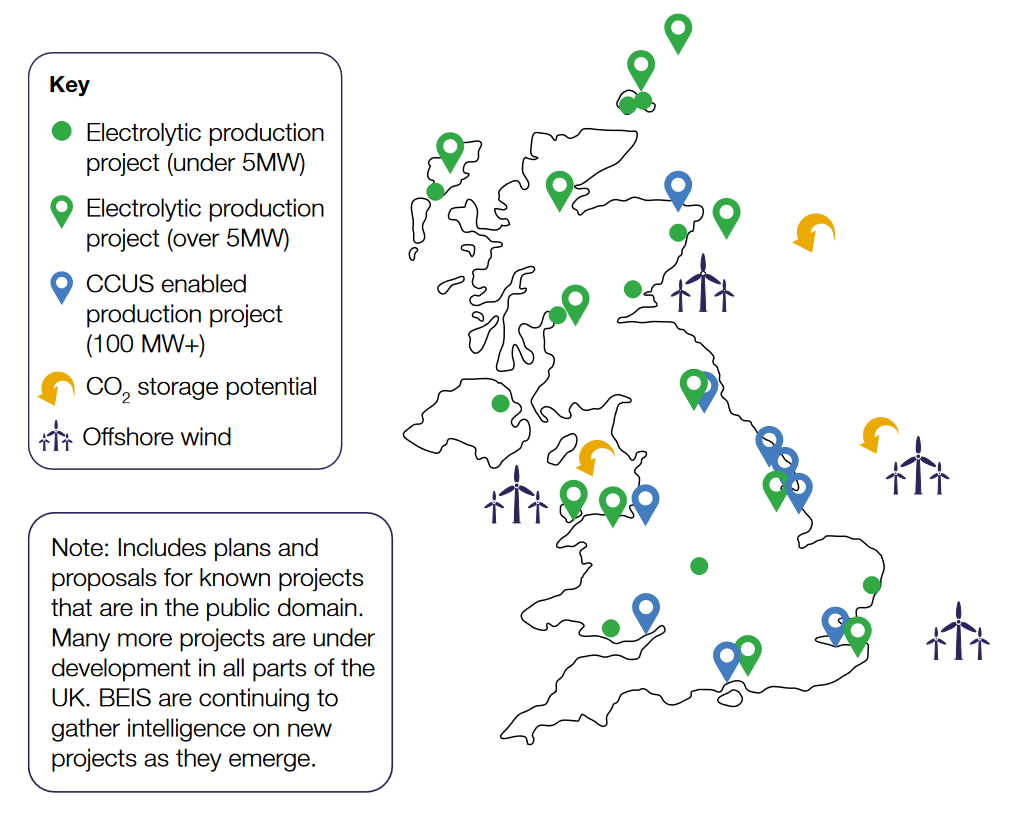

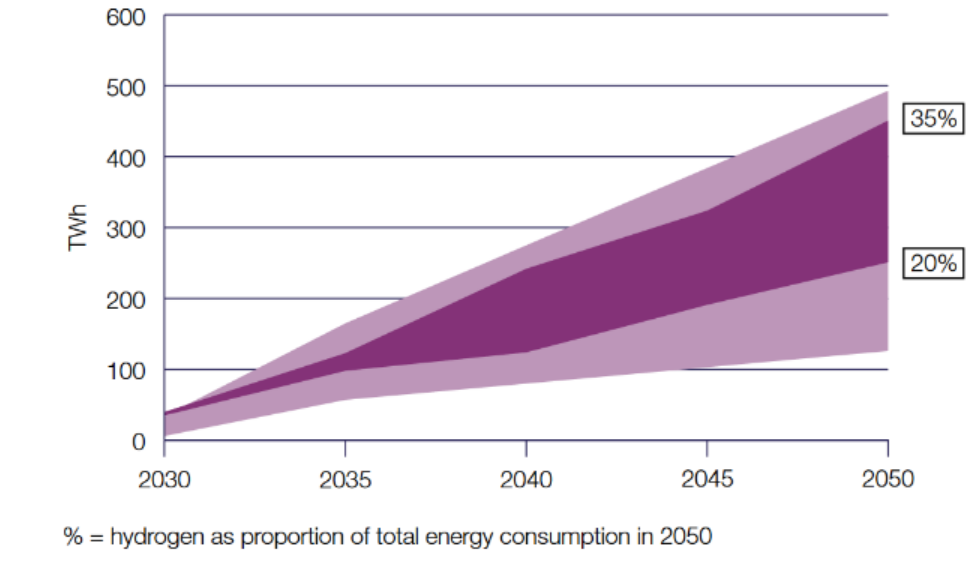

But excess power from offshore wind and other renewable sources also offers an even more dynamic area for energy cooperation: both the UK and Germany seek to ramp up their markets for hydrogen production. Akin to Germany's national hydrogen strategy, the UK's Hydrogen Strategy outlines its targets for increasing its share of all hydrogen production in the energy mix. Unlike electricity, hydrogen can be easily stored and used whenever it is needed. The UK has specific plans to increase its “low-carbon hydrogen” production, known as blue hydrogen, as well as green hydrogen, particularly since the start of Russia’s invasion.

Whilst blue hydrogen is produced from natural gas, where carbon dioxide emissions are afterwards captured and stored (CCS), to which the UK is willing to enable shared access with other European countries, so that it can be considered less damaging to the climate, green hydrogen is produced entirely from renewable energy. “Periods of excess offshore wind power can be used to make green hydrogen”, Evans also noted. This means the UK will gain the potential to expand green hydrogen production as its offshore wind capacity increases, he said.

And as Germany and many other EU countries are looking to seal green hydrogen trading deals with countries as far afield as Australia or Canada, an agreement with the UK appears conceivable too.

The embassy pointed to Wrightbus, a UK company based in Northern Ireland, as an example of “an export success story” in spite of Brexit. The company’s double-decker buses fuelled with hydrogen are being exported to continental Europe. Its fleet of fuel cell buses is the largest in Europe, and second largest in the world.