German government push is key to kickstarting EU industry decarbonisation

Europe's drive towards climate neutrality by mid-century puts enormous pressure on its energy-intensive industry to initiate the switch to low-emission production. Many experts say that a push by the new German government will be key to firing the starting gun for low-carbon investments worth many billions of euros, because both crucial policy decisions and major industry investments are pending. Many companies already have detailed plans for massive emission-cutting investments, and impatiently await new national and EU policies to enable business models to implement them.

"Germany's task now is to be one of the advocates for ambitious international goals both inside and outside Europe," said Jens Burchardt, the Boston Consulting Group's global expert on climate impact.

The decarbonisation of Europe's industry has been lagging behind other sectors, such as the power sector, but new climate-neutral targets have created a huge dynamism. Most industrial plants will have to operate without causing CO2 emissions by the middle of the century – otherwise they risk becoming stranded assets. As many large industrial plants, such as steelworks, steam crackers and cement kilns, are in use for several decades, companies have to opt for low-emission technologies today when replacing or modernising them.

"We have very little time because industry operates in long investment cycles," said Burchardt. "In order to achieve our climate protection goals, almost every company would have to choose a completely emission-free solution from now on for every major (re)investment in industrial plants," he told Clean Energy Wire.

The urgency of policy decisions is particularly pronounced in the steel industry. In response to climate targets, sector giant ArcelorMittal plans to launch low-emission plants in several European countries by the middle of this decade, as does Germany's thyssenkrupp at its steelworks in Duisburg. Final investment decisions must be made next year at the latest to stick to this timetable, because the companies will also need time for regulatory approvals and construction.

Golden opportunity at a critical time

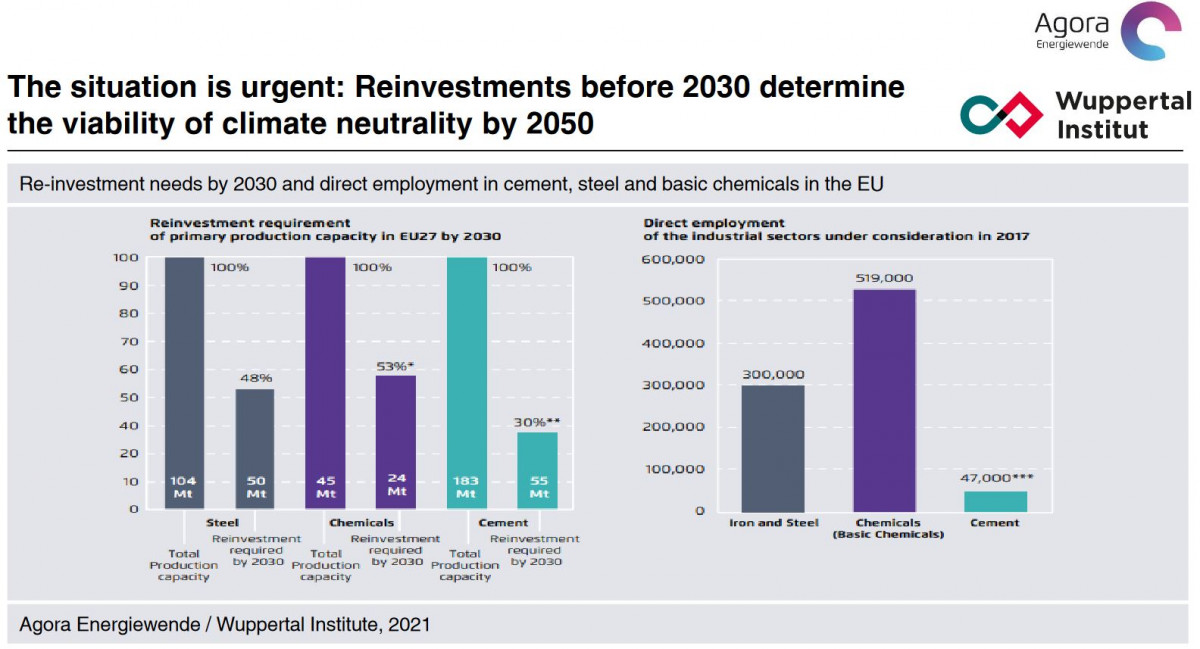

There's much at stake for Europe's industrial future and its economy as a whole. In the EU, iron and steel, chemicals and cement companies, which are in the crosshairs of decarbonisation efforts because of their large emissions, employ almost one million people. The good news is that decarbonisation technologies already exist – new production processes replacing coal with renewable hydrogen, direct electrification and resource efficiency, to name but a few.

Industry is even more central to Germany's overall economic prowess and its success as an exporting country. Industry’s share of total economic output, stable at over 20 percent for decades, is much higher than in most other developed countries. Germany’s entire manufacturing industry employs around seven million people (out of a labour force of about 44 million), and roughly 15 percent of them work in energy-intensive sectors.

Germany's entire industry is responsible for around a quarter of the country's greenhouse gas emissions, and the energy-intensive industry for around a fifth of the total. It is the second most emission-intensive sector behind electricity generation. The country plans to lower industry's CO2 output by around a third by 2030, meaning emission cuts in the sector will have to increase sixfold compared to the long-term average.

Many researchers see a "golden opportunity" for making a big leap in industry decarbonisation during this decade, because companies will have to replace or modernise countless existing plants over the coming years as they reach the end of their lifetime. This creates great urgency to get the right framework conditions in place in time, so companies will opt for low-emission technologies.

In the EU's steel, basic chemicals and cement industries, between a third and a half of total primary production capacity requires reinvestments by 2030, according to climate policy think tanks Agora Energiewende and the Wuppertal Institute.

The investments necessary for the transformation are huge. Germany's steelmakers have said 30 billion euros will be needed to make the existing facilities climate-neutral by 2050. Higher operating expenditures will come on top of this sum. According to Germany's industry association BDI, investments of about 860 billion euros will be needed across all sectors in the country by 2030 alone to finance the "greatest transformation in Germany's history."

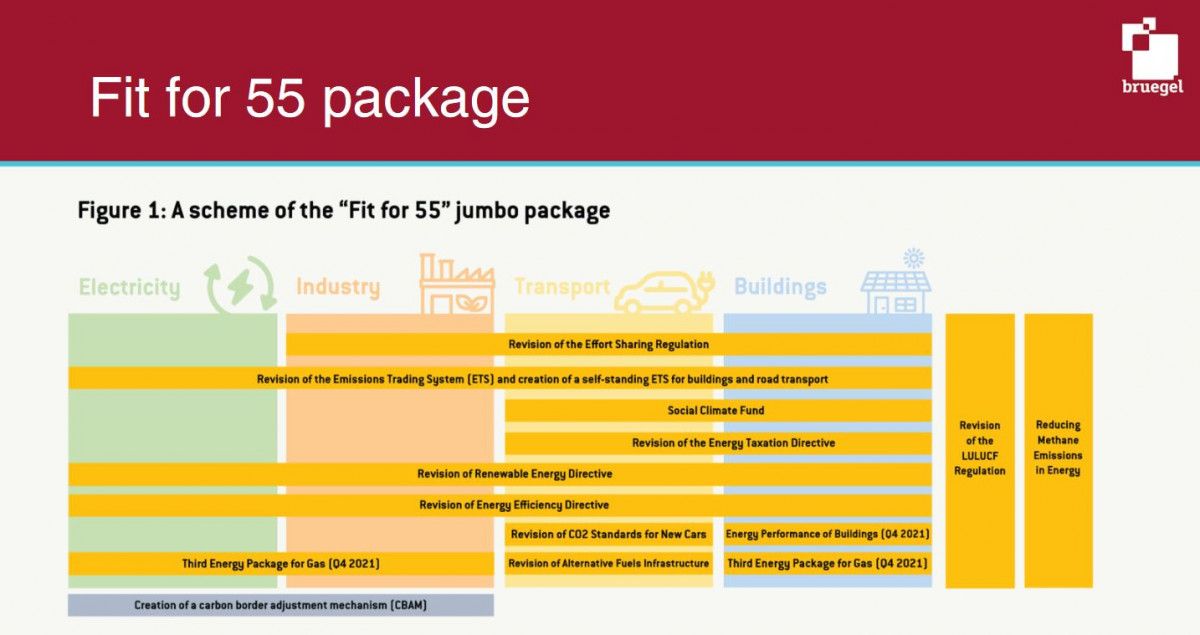

Fittingly, the new German government entered office at a crucial time for EU energy and climate policy. As part of its "Fit for 55" legislative package aimed at getting the economy in shape to deliver a 55 percent emission cut by 2030, the bloc will negotiate core changes to its energy and climate policies that will be central to industry decarbonisation this year. A reform of the European Emissions Trading System (ETS), the establishment of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), as well as changes to the EU's renewables and energy efficiency directives are among the issues on the agenda.

Germany's central role and responsibility

Experts consider it Germany's duty to push for policies on an international level to speed up industry decarbonisation because of its central negotiating position as Europe's largest economy and the bloc's industrial powerhouse.

"Without an active, constructive negotiating position on Germany's part, the EU's climate package, and with it the urgently needed support from Brussels for Germany's climate policy, cannot be brought to a successful conclusion," according to Agora Energiewende. "In the end, it is a European topic that we as Europe's largest economy have to push the most, but solve at the European level," said former Agora director Patrick Graichen shortly before he became state secretary in Germany's new climate and economy ministry.

EU economic policy think tank Bruegel also sees a central role for the new coalition during the upcoming climate negotiations at EU level. "The positioning of the new government on the ‘Fit for 55’ package in the EU Council will be absolutely central to whether the package can be adopted, and how much of it will be adopted," Bruegel director Guntram Wolff told a webinar last October.

"Germany definitely has a special responsibility to move industry decarbonisation forward," E3G industry expert Johanna Lehne told Clean Energy Wire. "Firstly, Germany is a key international player in climate negotiations. Secondly, Germany was able to position itself as a global leader in climate mitigation technologies in the energy sector, and we think it is now in a very strong position to do the same for industrial mitigation technologies. Thirdly, it is a major steel and chemicals producer and therefore it’s in a really good position to move things forward very quickly in these sectors specifically."

Boston Consulting's Burchardt stressed that Germany not only has a special responsibility but also a self-interest in pushing the issue internationally. "Among all large economies, we are one of those with the most to gain from climate protection: Replacing fossil energy imports with investments strengthens our economy. Moreover, as a technology exporter, Germany can gain a great advantage from positioning itself early in future technologies." He added there are few other countries that are as well positioned as Germany to take on a global pioneering role.

There is no time to lose in taking advantage of the transition, according to Bruegel's Wolff. "The rest of the world is not waiting. On the contrary, in China and the USA and other parts of the world massive investments are being made in industry and innovation, and we as Europeans have to prepare ourselves to continue to play at the forefront."

Coalition differences and financing are stumbling blocks

Germany's government has set itself an ambitious industry decarbonisation agenda, which forms a central part of the coalition agreement. The three governing parties – Chancellor Olaf Scholz's Social Democrats (SPD), the Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) – agreed to develop an industrial strategy that prevents carbon leakage, create instruments to support industry investments to lower emissions, ensure competitive electricity prices and ramp up the country's plans for establishing a hydrogen economy, among other plans.

But the coalition agreement remains vague on specifics, reflecting differences among the parties. These will have to be overcome before Germany can become an engine for the decarbonisation of European industry, according to E3G's Lehne. "There is a general sense that the new German government could speed things up at EU level when it comes to industry decarbonisation. But it will critically depend on whether the coalition can agree on an ambitious and unified position. It’s not yet clear that this will be possible."

Lehne pointed to EU plans for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) as an example of where parties differ. To protect Europe's industry during decarbonisation, the CBAM would introduce a levy on emissions of imported products made in countries with more lax emission rules. But the highly export-dependent German industry is worried that the CBAM could cause frictions in international trade, which could put sales at risk.

Whereas France has vowed to push this instrument during its current EU Council presidency, Germany has been a much more cautious proponent, partly due to industry scepticism. "Within the new coalition, the different parties clearly have different and slightly competing positions on CBAM, which is reflected by caveated language in the coalition agreement," Lehne said.

Economy and climate "super minister" Robert Habeck has said he considers reconciling emissions reduction with economic growth his most important task. During the presentation of an opening stocktake of the energy transition, Habeck said creating the legal and financial frameworks for carbon contracts for difference (CCfDs) to support industry in transitioning to climate-neutral production and scaling up the use of hydrogen are high on the agenda.

CCfDs are intended to give companies the planning security they need to invest in climate-neutral production. In long-term contracts, the state would promise companies to bear the additional costs of CO2 emissions reductions that exceed the price for CO2 allowances in the EU emissions trading (EU ETS).

Financing this comprehensive industry decarbonisation programme will be a delicate task, as the effects of the coronavirus pandemic have stretched public resources. An additional hurdle is the German government's commitment to a balanced budget.

Domestic policies and EU engagement equally important

Given the enormous challenges that need to be overcome before industry decarbonisation can take off in earnest, Germany's government will need to push innumerable policy levers at the same time. It will have to ensure the availability of huge amounts of green power and clean hydrogen, plan a CO2 infrastructure for Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), ensure that climate-neutral processes are competitive and generate market demand for climate-neutral materials, while also pushing energy efficiency and circularity concepts.

"A lot has to happen at the same time - individual measures are not enough," said Boston Consulting's Burchardt, adding the 2030 climate targets will require a complex climate programme to reshape regulatory incentives in all sectors. "This has to happen within the next two years."

While implementing this programme, the government can't afford the luxury to focus only on the national level. "Given how much investment is needed and how quickly we need to move, both EU and national policies are crucial at this stage," E3G's Lehne said. "Historically, industry decarbonisation policies are centred at the EU level. Most member states don't have industrial decarbonisation policies in place. But we would like to see that change. More movement at the national level – like in the Netherlands, Sweden and maybe Germany now – makes a fundamental difference. Member states that do more on the national level also advocate for more ambition at the EU level." Sweden is considered a frontrunner in green steel production, while the Netherlands are actively promoting green hydrogen for industry decarbonisation, with the Port of Rotterdam aiming to become an international hydrogen hub.

Germany will have to complement EU policies with additional national initiatives to reach its more stringent national climate targets. Whereas the EU plans to be climate-neutral by 2050, Germany last year agreed to reach that five years earlier, in 2045.

"Because Germany has higher ambitions than others within the EU, we also need to do more at the national level," said Burchardt. "Measures at the EU level alone will not be enough to stimulate our higher national targets. This means we need the incentives earlier and have to readjust nationally."

Beyond Europe: G7 and climate club

Given German industry's dependence on exports, the sector and experts stress that the government also needs to look beyond the EU in its drive for cleaning up industry. "Climate policy is only successful if it is international," industry association BDI argued in late November. "National and European solo efforts do not help."

The government has already said that the climate crisis will be at the centre of its G7 presidency, which started at the beginning of the year. Chancellor Olaf Scholz is also a staunch supporter of establishing a "climate club," a partnership of countries with the highest ambitions for climate policy worldwide, in order to give implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement a further boost and at the same time protect domestic industry from competitive disadvantages.

"The G7 presidency gives Germany a lot of scope to push the topic internationally," said Lehne. "Last year, the G7 initiated an industrial decarbonisation agenda, and Germany has signalled its interest in taking that forward and pushing the idea of a climate club within that context. There are still many open questions on how that could work in practice, but it is great progress compared to five years ago, when this simply wasn't an issue at the G7."

Bruegel's Wolff said the climate club could become an important tool for pushing industry decarbonisation beyond the EU. "I think we should go in this direction. We must create additional incentives in order to manage faster decarbonisation […] It will not be enough to only use the CBAM. We will probably also need technology transfer and climate financing as part of the package."

Start of new government creates optimism

Despite the enormous challenges ahead to get industry decarbonisation off the ground, there is a general sense that Germany's change of government has brought a new urgency to the topic, after the issue made little headway under the previous government. Industry association BDI has said the restructuring of government ministries itself bodes well to making progress.

"Placing climate protection in the ministry of economic affairs does justice to the BDI's view that industry can and wants to be a central problem solver on the way to a sustainable economy," the lobby group said.

Other experts are also cautiously confident that industry decarbonisation will begin in earnest under the new government. "All in all, the coalition agreement and the start of the government give cause for optimism," said Burchardt. "The issue has gained new momentum, and the level of ambition and seriousness is in another dimension. The coming months and years will show whether this is enough."