German government MPs agree climate law reform that weakens sector targets

The parliamentary groups of Germany's governing coalition – the Social Democrats (SPD), Green Party and the Free Democrats (FDP) – have ended a months-long dispute and decided on a reform of the country's climate action law which would weaken the emissions limits for individual economic sectors. The reform would also oblige any new government to present policy packages during the first year in office to ensure that national climate targets are met.

"We are turning German climate policy on its head," said Lukas Köhler, deputy head of the FDP's parliamentary group, adding it would no longer matter in which sector emissions are reduced. "From now on, the only thing that counts is that the climate targets are achieved overall." Matthias Miersch, deputy head of the SPD's group in parliament, said that "under the amendment, not a single gram of CO2 more may be emitted" than under the current climate law.

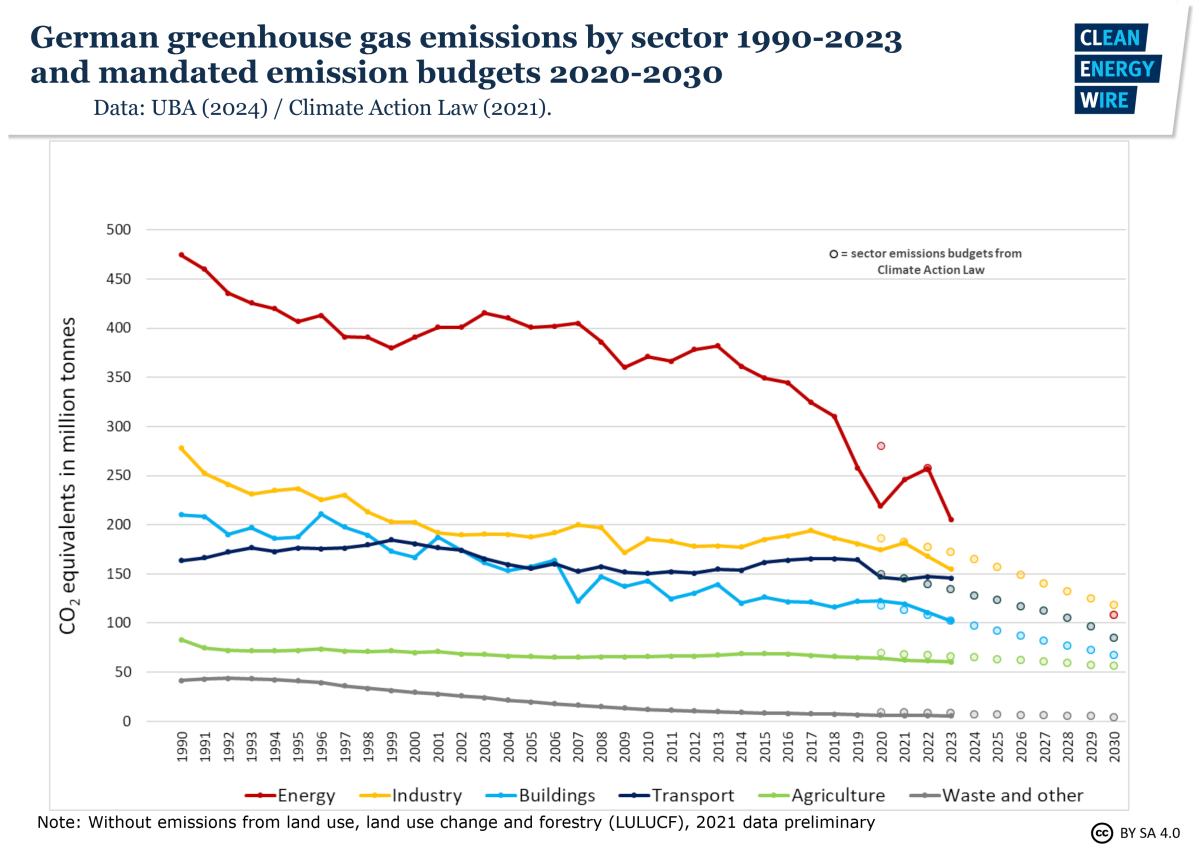

Germany's climate action law stipulates that the country must reach greenhouse gas neutrality by 2045 and meet interim emissions reduction targets: 65 percent by 2030, and 88 percent by 2040, in comparison to 1990 levels. Until 2030, Germany currently has sector-specific annual emissions limits. With the reform, an overshoot in specific sector would no longer mean that the responsible ministry has to come up with an immediate programme of climate measures to put the sector back on track.

Energy industry association BDEW criticised the weakening of sector limits. "It will not help the climate," said the lobby group's head, Kerstin Andreae. "It takes the pressure off individual sectors to step up their climate protection efforts." The energy sector has until now stayed well below its emissions limits, and Andreae emphasised it should not be expected to make up for the shortfall of other sectors. Especially the FDP-led transport ministry is lagging far behind in making the sector more climate-friendly.

The agreement comes after months of delay in the legislative process, as the coalition partners were unable to see eye to eye on the reform. The FDP strongly advocated for the reform, while many parliamentarians from the Greens rejected the weakening of sectoral targets. In its coalition agreement, the government said that it aimed to reform the climate law in this way, with the cabinet agreeing to the reform last summer. However, it still has to be approved by a majority in parliament. Yesterday's agreement paves the way for a vote in the legislature during its next session, possibly as soon as August.

One sector can compensate for another

The lawmakers have not yet presented the actual text they agreed on, and some details remain unclear for now. The original draft law by the cabinet had said that, officially, the annual emissions limits for each economic sector – energy, industry, buildings, transport, agriculture and waste – remain in effect and will continue to be monitored.

However, they will have much less significance. A missed target in the previous year no longer means that the ministry mainly responsible for the sector is required to present immediate measures to bring it back on track.

Instead, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) will each spring present projections on how greenhouse gas emissions might develop in the future, based on current and planned policies. Should these projections show two years in a row that Germany is off track to reaching its climate targets for all sectors combined, the government must present a programme of measures to close the gap across sectors. That means that one sector overachieving its targets could compensate for another sector lagging behind.

One month ago, the UBA presented projections for the years up to 2050, which showed that Germany is set to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 64 percent by 2030, and by 83 percent by 2040. The targets for those years respectively, however, are 65 percent and 88 percent. If there were two such years of projections in a row, the government would have to present a programme of measures to get the country back on track.

"We must acknowledge that the obligation to launch new programmes in individual sectors every year, if targets are missed, does not automatically lead to achieving our climate targets," said the SPD group leadership in a letter to its members, seen by Clean Energy Wire. "In the building and transport sectors in particular, in addition to short-term measures, multi-year programmes are also required that can only take effect over the course of several years."

The government has argued that the focus on future developments guaranteed more planning security for society and the economy, and enabled Germany to reduce emissions where it is fastest and most efficient.

The reform would also require each new government to present a climate action programme during the first year in office that would ensure that the emissions reduction targets for 2030 and 2040 are met.

Reactions: Government "successfully got itself off the hook"

German governments will now be measured by what they are planning for the future, not by what they are achieving in the present, writes journalist Michael Bauchmüller in an opinion piece in Süddeutsche Zeitung. "Such plans are always easy to forge, and they are also easy to furnish with forecasts of what they will achieve for climate protection. At some point in the future. Whether this actually happens, whether the next government changes the plans again or runs out of money in the meantime – these are the problems of the next legislative period," writes Bauchmüller. "Seen in this light, this government, and above all its transport minister, has now successfully got itself off the hook.”

Civil society group Germanwatch called the reform agreement "a major political step backwards." The government aimed to "give itself carte blanche not to have to adopt any more climate protection measures in this legislative period," said the organisation's head of German and European climate policy, Simon Wolf. "This is disastrous, because achieving the 2030 target is anything but certain."

The Council of Experts on Climate Change said on Monday (April 16th) that a climate programme the government introduced last year is less likely to achieve the projected emissions reductions than envisioned, also due to reduced financial leeway following a constitutional court ruling.

Environmental Action Germany (DUH) called on parliament not to go through with the reform. "By gutting the law in this way, Parliament would be violating the rights of future generations and all people who are already suffering massively from the climate crisis today," said managing director Jürgen Resch.