German election primer – 2038 end date for coal under fire as climate forecasts worsen

What does the coal phase-out law say?

What does the coal phase-out law say?

- Germany's coal exit was formally sealed in mid-2020, when parliament adopted a phase-out law largely based on a compromise found by the country's coal exit commission. After two years of debate, the advisory body consisting of various stakeholders, including industry, environmental groups and policymakers, had agreed on 2038 as the very latest date for taking the last coal plant offline. But the door was left open for an earlier exit in 2035, provided that power supply security is guaranteed.

- Job security and economic stability in the affected coal mining regions played a big part in the agreement, as the local coal industry is often the largest breadwinner there and economic activity is centred on it. In order to avert a collapse of local economies, particularly in eastern Germany, and avoid entire regions becoming estranged from the energy transition, the government ended up providing 40 billion euros in structural support payments to ensure a "just transition" in the regions that would minimise social distortions and pave the way to an economic revival supported by renewable power investments.

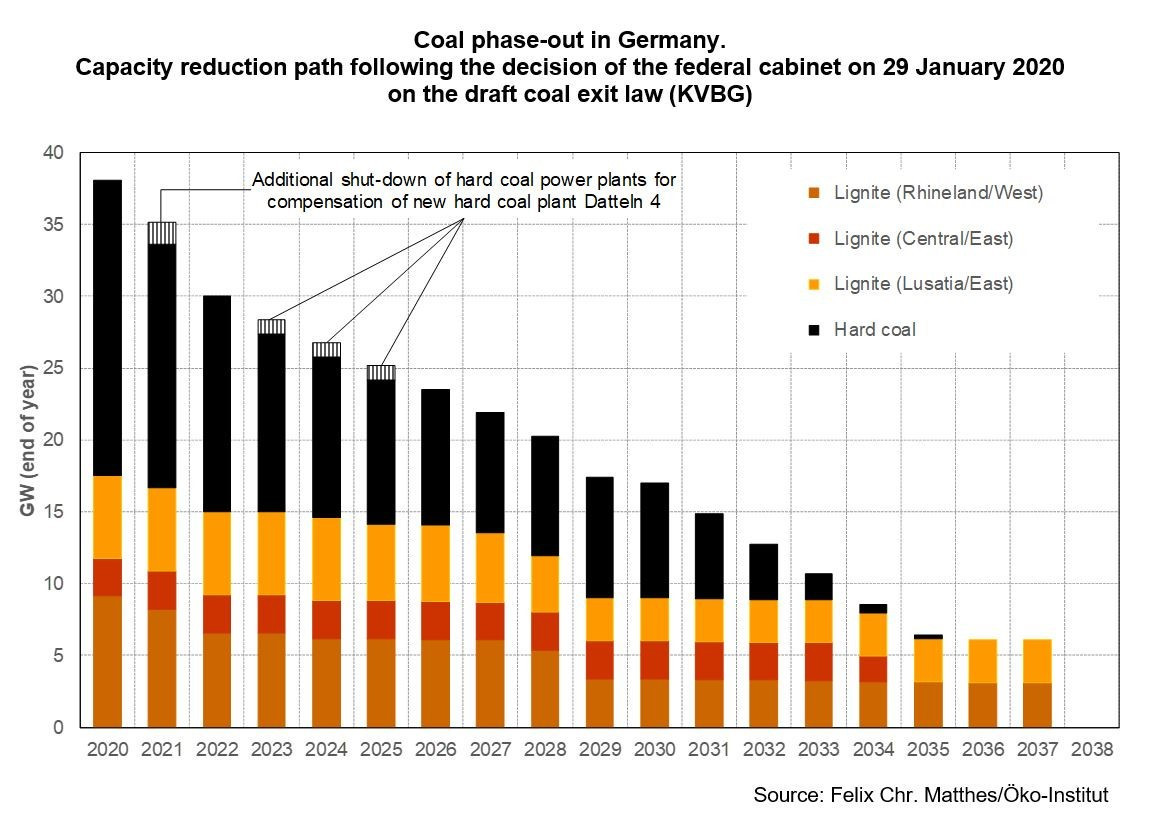

- The coal exit law also granted "compensation payments" to operators of the lignite plants running on domestic coal supply, whereas hard coal plants that use imported coal had to participate in tenders that award low compensation demands. Plant closures were scheduled in a fixed timetable (see graph below) that could only be changed at the federal network agency's (BNetzA) behest to preserve grid stability. The deal saw RWE and LEAG receive compensation amounting to 4.35 billion euros in return for shutting down operations.

- But while the commission agreement was intended to prevent a major conflict around the phase-out, the corresponding law was widely criticised. Environmentalists and independent researchers said the law deviates from the commission's compromise on key issues. In its current form, it is said to fall short of climate targets, grants coal companies too much compensation, and effectively prolongs the running time of coal plants given tightening market conditions.

What role does the coal exit play in the election campaign?

What role does the coal exit play in the election campaign?

- The end of coal in Germany dominated the climate agenda in the 2017 election campaign and the government attempted to settle the issue for good by finally signing an agreement three years later. In the meantime, however, Germany's emissions reduction efforts had to be levelled up due to increased EU targets and a landmark ruling by the country's constitutional court compelled the government to bring forward its target year for climate neutrality by five years to 2045. Several senior politicians, both from the government and from opposition parties, have since weighed in, saying the coal exit's agreed conditions should be revisited:

- Green Party chancellor candidate Annalena Baerbock said a phase-out in 2038 "is not compatible" with the new climate targets. "I campaign for an exit in 2030," she said and reiterated that her party would only enter into a coalition government that aims for reaching the Paris Agreement's target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. "There will be no compromises," Baerbock said, adding that the Greens would introduce a programme that outlines how to achieve this goal within the first 100 days of government.

- The same year has been proposed by Bavaria's state premier Markus Söder of the CSU, an internal rival of CDU chancellor candidate Armin Laschet within the two parties' alliance, calling the current target year "unambitious”.

- Laschet, on the other hand, said the rising price for emissions allowances in the EU trading system ETS could mean "the exit will happen quicker than we all think”. He added that his home state North Rhine-Westphalia would be able to complete it as early as 2030, but stopped short of announcing an exact alternative to 2038.

- Peter Altmaier, economy and energy minister for the CDU, also stated that the phase-out "will happen faster than initially thought" due to rising allowance prices. However, in its election programme the CDU/CSU alliance said it would continue to support the agreement.

- CDU energy politician Andreas Jung said emissions allowance prices in the European system ETS ultimately would decide how long coal power will be used. "My personal opinion is that we will leave coal before 2034," he said

- The Social Democrats' (SPD) top candidate Olaf Scholz also said he would prefer ending coal before the very last year envisaged in the Coal Exit Law. "I want to make it happen," Scholz said, qualifying a statement made in front of coal workers a few days earlier, where he stated that the exit law should be fully implemented. "We have an agreement to leave coal and also an end date – but we also have regular evaluations that allow an earlier phase-out, so 2038 just is the last possible year," Scholz said. He added that the end of coal depended above all on a fast roll-out of renewable power installations, which would be an absolute priority for him, should he lead the next government.

- His fellow SPD member, environment minister Svenja Schulze, said she regards an earlier end for coal as as absolutely necessary due to the tightened targets.

- Volker Wissing, presidium member of the pro-business party FDP, said: "The aim has to be to end coal early – and we can do it." However, he also said the exit would hinge on adequate renewable power expansion and warned that this should not result in industry and households ending up paying more for energy than they already do.

- The leader of the Left Party, Janine Wissler, said her party also favoured an end of coal-fired power production in 2030, arguing that renewables expansion has to be "enforced" to ensure the conditions for a phase-out are met.

How far has the coal phase-out progressed since the compromise was found?

How far has the coal phase-out progressed since the compromise was found?

- The first installations were taken offline at the end of 2020 and more are to follow by the end of 2021. By the end of 2022, the total capacity is supposed to drop to 15 gigawatt (GW) hard coal and 15 GW lignite, from 22.8 GW hard coal and 21.1 GW lignite in 2019. For 2030, the current targets are 8 GW hard coal and about 9 GW lignite.

- Hard coal phase-out auctions have so far largely been deemed a success, with bids per megawatt taken off the grid being far below what grid authorities had planned. Operators concluded that taking even the most modern plants offline is more economical for them, as the example of Hamburg's Moorburg plant, opened in 2015, demonstrated.

- Many climate activists took issue with the fact that the law did not rule out the start of operation of a new coal plant, Datteln 4 by operator Uniper, at a time when the country was trying to find a compromise on phasing out coal. The plant started operation in mid-2020, after years of delay, and was given an operating license until 2038, meaning it would be among the last installations in the country to go offline. However, Uniper since has signalled it would consent to an earlier closure if a future government demands it. A German court recently found that construction plans for country’s newest coal plant did not meet legal requirements, possibly the first of two steps that could lead to the plant's immediate shutdown. The ruling is seen as a blow to conservative candidate Laschet, who strongly backed the plant in his home state.

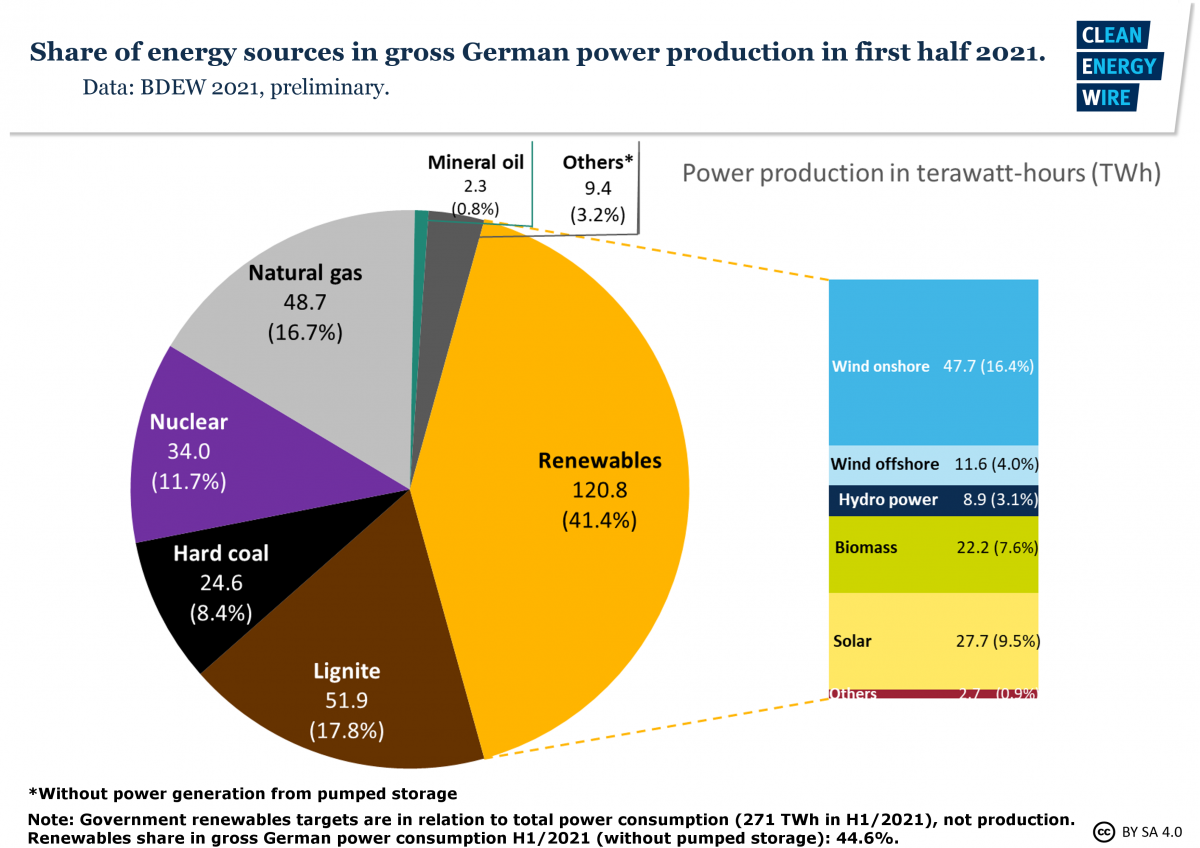

- While coal power generation markedly increased in the first half of 2021 compared to the year before, when the coronavirus pandemic massively reduced economic activity and energy demand, it still remained lower than in 2019, meaning a downward trend generally was sustained. Altogether, coal provided just over a quarter of Germany's total power production in the first six months of 2021 (see graph).

- However, forecasts by think tank Agora Energiewende found that a strong rebound in economic activity in 2021 will likely mean that Germany is going to see its strongest year-on-year rise in emissions since 1990 and exceed the CO2 limit it managed to meet in 2020.

- According to the think tank, this means further immediate steps to reduce emissions, including an earlier end of coal-fired power production, cannot be avoided. However, Agora said it estimates that coal would drop out of the market anyway by 2030 under a reformed ETS, with prices rising above 80 euros per tonne and making coal unprofitable in most of Europe.

Why is the agreed phase-out model being contested?

- While many negotiation partners in the coal commission criticised what the government had made of the compromise right after the law was introduced, worsening climate forecasts, tighter climate targets, and events such as the deadly floods sweeping parts of Germany in the summer only fuelled calls to reconsider the agreement. But the government coalition was criticised in media comments for shying away from resolving the big contradiction of increased climate action and sticking to the late end-date for coal to avoid alienating trade unions or break their promise to coal workers.

- Environmental NGO Greenpeace calculated that coal power operation as provided by the current law could use up almost half of Germany's remaining carbon emissions budget of roughly 4.4 billion tonnes under a trajectory that aims to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Sticking to the phase-out schedule thus would drastically reduce all other sector's budgets. Depending on the speed of the roll-out of renewable power sources, coal's share in the remaining budget could even be as high as 74 percent, it added.

- Climate analysts at think tank E3G pointed out that Germany’s new climate target of becoming greenhouse-gas neutral by 2045 cannot be achieved if emissions from the energy sector aren’t cut quicker than foreseen in the coal exit legislation. A draft government report from August backed this assessment, finding a large gap between estimated greenhouse gas emission reductions and targets over the coming 20 years. Without further action, 2030 emissions will have decreased by only 49 percent, and not by 65 percent as planned, the report found.

- Energy market analysts at Energy Brainpool found that "the reduction in coal-fired power generation remains by far the greatest leverage in terms of emissions”, but also stressed that a quicker phase-out must come with faster renewables expansion. If the end of lignite alone was brought forward to 2029, the necessary share of renewable energy sources in gross electricity consumption would have to climb from 65 to 75 percent in 2030, they calculated.

- Environmental NGOs also criticised the bill presented to the taxpayer, arguing that the over 4 billion euros agreed in compensation payments to lignite plant operators are far too much. Given the changing market environment, roughly 343 million euros would already have covered the companies' losses, they argued. Operators would have had to shut down earlier anyway due to market forces making coal power unprofitable. The guaranteed funding now would give them financial leverage to keep installations running, they argued. The plans are currently being scrutinised by the European Commission to see whether they are in line with EU State aid rules.

- Researchers at the Wuppertal Institute warned that the next government faces "the task of the century" to prepare the country for a rapid decline in greenhouse gas emissions and must enforce an earlier coal exit in 2030 to achieve them. "The next legislative period is the crucial time to turn the 2020s into a decade of implementation and to enter the climate protection path irreversibly," the institute's scientific director Manfred Fischedick said.

All texts created by the Clean Energy Wire are available under a

“Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY 4.0)”

.

They can be copied, shared and made publicly accessible by users so long as they give appropriate credit, provide a

link to the license, and indicate if changes were made.