German election to define speed and shape of energy transition

The German federal election is almost upon us, and how the country votes on September 24 could have a profound impact on the course of the Energiewende.

The process of weaning the world’s fourth largest economy off nuclear and fossil energy already has decades of history and will continue under the next government, regardless of which parties take power. “Germany's political system, its cooperative federalism and the strong role of civil servants ensures long lines of continuity beyond legislative terms,” says Arne Jungjohann, an energy policy analyst.

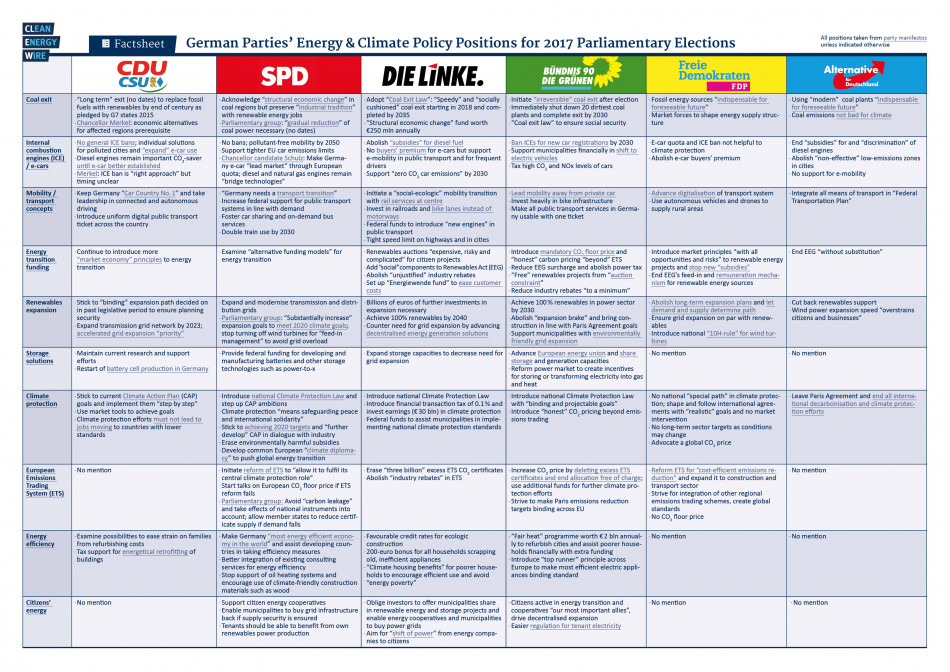

But the parties vary considerably on how they want to pursue the goals of the energy transition, and how much priority they give it over other issues. “What is in question, is the Energiewende's ambition under the new coalition,” says Jungjohann, a member of the Green Party.

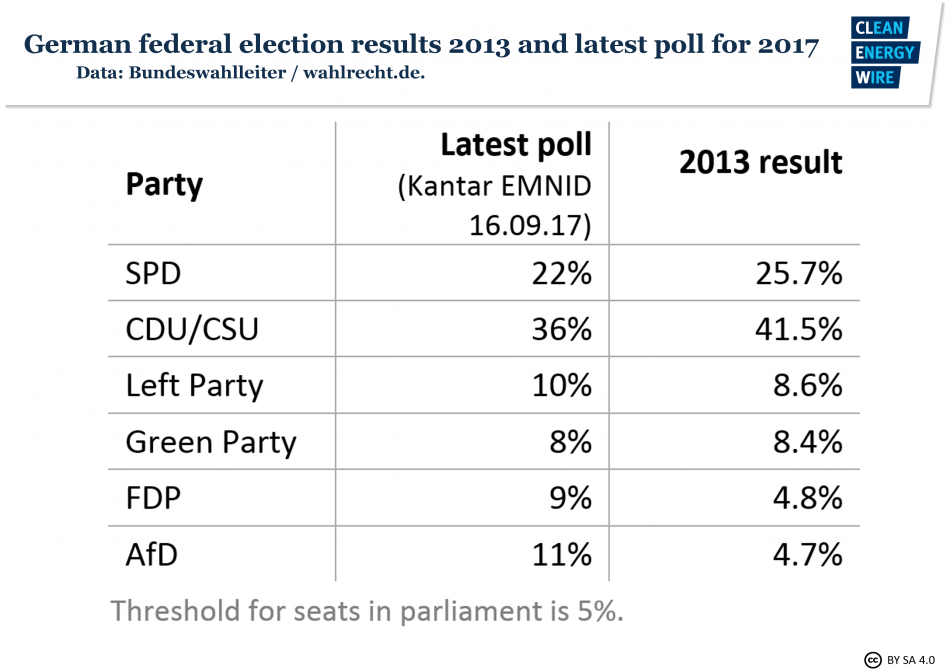

After an uninspiring campaign, where some international observers detected signs of complacency in a country with record employment, solid growth and stability, Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union enjoys a solid double-digit lead in the polls at around 37 percent, ahead of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and its candidate for chancellorship, Martin Schulz.

Barring a massive upset on election night, Merkel’s fourth term as chancellor looks like a done deal. But the make up of the coalition she heads will ultimately determine the form and speed of the Energiewende.

Germany is currently on course to miss its 2020 target of a 40 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions, compared to 1990, by a wide margin. Merkel -- dubbed the “Climate Chancellor” for her commitment to climate protection in the international arena -- will be under close scrutiny to see whether she can get the country’s climate efforts back on track. During the election campaign, Merkel promised to meet the targets, but many doubt this will be possible in such a short time.

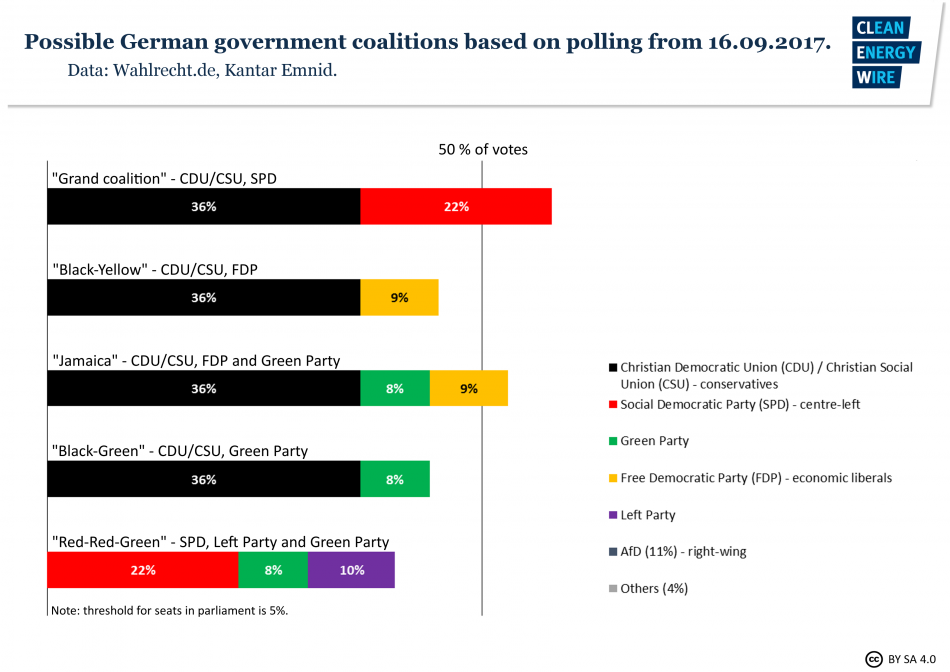

Germany’s system of proportional representation makes a coalition government the norm rather than an exception. And that complicates things. Merkel may be leading an alliance of parties with very different priorities, which will have to compromise on their manifesto pledges.

[Download the table as a JPG in full resolution here and as a PDF with active links here.]

Security, migration and integration of immigrants have been the only issues to raise emotions during the campaign debates. Energy and climate took a back seat, despite the Greens making it a campaign priority.

Thanks to the diesel scandal, the question of clean mobility did make a significant appearance on the election agenda. And surveys showed most Germans see climate change as a major problem.

However, it plays a minor role in how the electorate votes, as people most consider the Energiewende and climate action a cross-party commitment. The Energiewende enjoys strong public support, even as businesses complain about electricity prices and individual projects such as wind power installations or grid infrastructure trigger protests.

Race for third place

The real nail-biter on election night looks set to be the battle between the smaller parties, whose share of the vote will determine the coalition possibilities.

Forming a new government could then take weeks, if not months, as parties first sound out coalition options and then begin negotiations. Some parties will have to go back to their membership base for approval, further prolonging the process.

The Left Party, Free Democratic Party (FDP) and Green Party are close in the polls. But the right-wing, climate-change denying Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) is slightly ahead of all three. Set to be the first far-right party to enter federal parliament, it could take third place behind the CDU/CSU and SPD.

The AfD’s surge in the wake of the refugee crisis is an unpredictable factor for pollsters and for German politics in general. But since all other parties have ruled out a coalition with the AfD, polls indicate only a renewed “grand coalition” of CDU/CSU and SPD and a “Jamaica” coalition (named for the parties’ colours, which make up the Caribbean country’s flag) of the conservative CDU/CSU, FDP and Greens as viable options to form a stable government.

The traditional centre-right alliance of pro-business FDP and CDU/CSU, which governed from 2009 to 2013, remains possible, though media have reported unease about this combination in Merkel’s chancellery. The Free Democrats, who failed to enter parliament in 2013, would also have to rebuild their structures in Berlin, which makes assuming responsibility in a large number of ministries more difficult.

The most straight-forward option would be another grand coalition, which enjoys solid, if dwindling approval among voters. But energy and climate observers have pointed out that both parties have remained vague on energy and climate measures, and fear this combination would lack the drive for decisive action.

Newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung’s coalition analysis said this combination would stand for a “determined more of the same”. Whether SPD members will sign-off another coalition agreement with Merkel seems also uncertain because many feel the party hasn’t benefitted from being part of the current government.

Setting the course for the future of the Energiewende

The present coalition’s climate policy record has failed to convince. Energy industry experts and analysts credit former SPD economy and energy minister Sigmar Gabriel (who moved to the foreign ministry late last year), and his energy state secretary Rainer Baake, for putting the Energiewende project in order and tackling a number of key areas.

They worked through a 10-point plan set out in 2013, including a new electricity market design that rejected utilities’ calls for a capacity market. But they also irked the renewables industry with a shift from guaranteed feed-in tariffs to an auction-based system and a cap on new installations.

Most environmentalists blame the government’s lack of action on coal-fired power generation and in the mobility sector for stalling greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Household power prices have remained largely stable over the past four years, but taxes and fees now account for more than half of retail prices.

Merkel won praise at home and abroad for her commitment to climate protection, making Germany a driving force behind the Paris Agreement on climate change and keeping the other G20 countries on course when the United States dropped out.

The grand coalition also managed to agree on a Climate Action Plan 2050 that includes the first sector-specific emission reduction goals. But key decisions and measures needed to meet these targets have been postponed until after the election, leaving decisions that will define the course of the Energiewende to the next government.

Environmentalists, businesses and academics have a long wish list on energy and mobility policy, well beyond the overarching question of climate protection. Industry continues to push for cost control and a focus on competitiveness. Energy experts demand an overhaul of levies and taxes on electricity – including the surcharge to finance renewables – in order to allow for the electrification of transport and heating.

All point to the need for investment in the power grid and digital infrastructure. Environmentalists want a defined coal phase-out, an end to petrol- and diesel- powered cars, as well as a decisive drive to make buildings and heating more energy-efficient and climate-friendly.

Compromise between environmentalists and free marketeers?

The Economist magazine wrote in a recent leader that Merkel should team up with the Free Democrats and Greens to avoid “more sleepy stasis”.

But whether a coalition of conservatives, FDP and Greens would be able to work together given their conflicting priorities is already hotly debated. “Energy and climate policy could prove to be a significant hurdle for any ‘Jamaica coalition’ at the federal government level,” Deutsche Bank analysts wrote in a note to clients.

In the final days of the election campaign, leaders Christian Lindner (FDP) and Cem Özdemir (Greens) stressed the extent of the gulf between their parties. The Greens have made giving up both coal and the combustion engine cornerstones of their election manifesto, while the Free Democrats want market forces to decide on the best low-carbon technology, and keep German climate targets in line with the European Union’s lower near-term climate targets.

Yet political scientists say none of this pre-election positioning will prevent a coalition. Leaders’ pragmatism may prove decisive, says Christian Stecker, senior research fellow at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES), who has analysed the party manifestos.

Stecker points to the Greens’ coalition state government with the CDU in Baden-Württemberg. “Since the success of [state premier Winfried] Kretschmann, the Greens seem to be less tied by red lines on environment policy,” he says.

Lindner and Özdemir had their first show down on energy policy at the annual conference of utility association BDEW in June, and observers noted how well the two party leaders got along.

The Greens and Free Democrats have also formed two state governments together, including in a Jamaica coalition with the conservatives in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany’s Energiewende posterchild. Their coalition agreements in the federal states suggest that the compromise reached between in the parties will have much more influence on policy than anything in their campaign manifestos.