Funding, burden sharing of climate action loom over quiet coalition talks in Germany

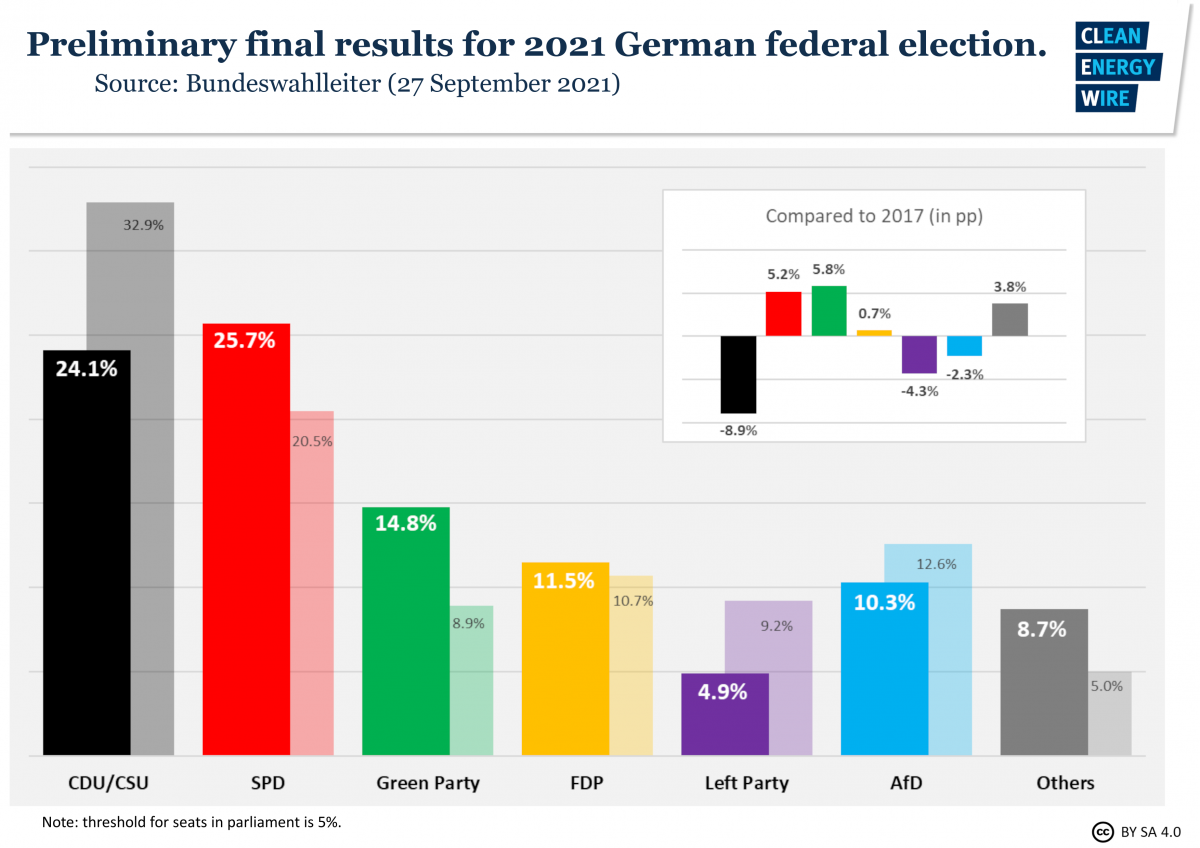

The three parties committed to forming the next German government coalition have the ambitious plan to conclude their talks by late November and present a coalition treaty that allows the country to abide by the Paris Climate Agreement. The so-called “traffic light coalition” (Ampel-Koalition) parties – named after the party colours of the Social Democrats (SPD – red), the Free Democrats (FDP – yellow) and the Green Party – started negotiations in individual working groups at the end of October. The talks aimed at making SPD candidate Olaf Scholz Germany’s new chancellor are held behind closed doors as the partners want to avoid them getting derailed by parallel public debates.

Although little information has come out of the talks so far, the participants’ different ideas on how far-reaching climate action measures should be financed and how the social impacts of the transition towards a climate-neutral economy could be managed suggest that this will be one of the negotiators’ toughest nuts to crack. As each party has to keep the interests of its own core supporter groups in mind, striking a balance between the demands of voters hoping for more ambitious climate action policies by the Greens, workers from low-income households hoping for support by the SPD and high-wage earners and businesses betting on the FDP require compromises at a time when world leaders are meeting for the COP26 in Glasgow under increasing pressure to agree on joint solutions for combating global warming.

The coalition negotiators are urged on by worsening climate change forecasts. Researchers and government advisors warn the country has no more time to lose and must open the coffers for decarbonisation projects if it wants to come close to achieving climate neutrality by 2045. The outgoing administration of chancellor Angela Merkel set this goal after a landmark court ruling that obliged the government to spell out speedier emissions reduction plans in more detail. National development bank KfW estimates that five trillion euros in private and public investments are necessary over the next three decades to meet the new target.

To complicate matters, the coalition negotiations take place at a time when energy prices in Germany and Europe rise at the fastest pace in decades. Soaring costs for natural gas, fuel and electricity have reduced the country’s growth outlook and stoked fears among businesses and households about the consequences of the emissions reduction measures like carbon pricing.

European energy price crisis shines spotlight on concerns of households and businesses

“Irrespective of current developments on gas and oil markets, Germany’s power prices will be under pressure in the next years,” Thomas Engelke of consumer protection organisation vzbv told Clean Energy Wire. Rising demand for clean electricity as well as CO2 pricing are poised to keep energy costs high, while new price hikes for fossil fuels are still possible anytime and “entirely independent of national climate and energy policies.” In order to avoid energy costs becoming a constant threat for the government, the three parties would have to decidedly pull together, Engelke argued. “None of them must shun this great responsibility.”

Like households, companies are concerned that a mix of high energy costs and tighter rules could hit their business. Alexander Stork of association BVMW said many in the country's famed Mittelstand -- small and medium-sized industrial companies that are the backbone of the country's economy -- were already facing strict environmental regulation through legislation like the forthcoming EU taxonomy for sustainable finance or supply chain monitoring.

A reliable and affordable energy supply would therefore play an “elemental role” in helping companies to cope with tougher conditions, Stork told Clean Energy Wire. Since Germany will finally end nuclear power by the end of next year and the “traffic light” parties are eyeing a faster coal exit, expanding renewables will be the key. “Small and medium-sized companies have a huge potential to tap into here,” Stork said. “Active support” for businesses through reduced bureaucracy and faster licensing of new projects was a prerequisite for this to happen.

Different party identities promise struggle over protecting core voter groups

Diverging party priorities and political identities suggest that getting an agreement on costs and funding will be not easy. The budding “traffic light coalition” presented a first paper laying out the general direction of their possible coalition agreement before starting formal talks. The draft contained a commitment to turbocharge climate action by boosting renewable power capacity expansion and other measures. But the document offered no details on how to finance what Scholz called “Germany’s biggest industrial modernisation in a century” and where voters may feel the impact on their wallets and lifestyles. Given that each party had campaigned on its very own platform regarding how Germany should utilise its economic strength and on which projects it should spend – or not spend – its precious public money, the caution about spelling out the climate action’s costs and consequences does not come as a surprise.

The SPD won the election presenting itself as the protector of low-income households and blue-collar workers. The party says it is determined to shield those groups from losing purchasing power and to improve social justice in broader terms. The strategy helped the centre-left SPD to re-establish itself as the favourite among workers, a traditional stronghold it had lost in the previous vote. Apart from raising the national minimum wage to 12 euros per hour, the Social Democrats promised stable pension levels and financial relief for low-income households, which the party wants to fund by taxing high-income earners. In a nod to fears that ambitious climate action could hurt their purchasing power, frontrunner Scholz has promised that “there won’t have to be any major sacrifices” in society at large.

SPD energy politician Johan Saathoff offered a glimpse what this could mean when he talked about a carbon price of 25 euros per tonne at the beginning of the year: “I believe that we would have been threatened by yellow vests if other people's price ideas had been implemented,” Saathoff said, referring to the wave of protests against higher fuel prices by so-called “yellow vest” activists in France. “We, the Social Democrats, have always said that we don't want to lose people on our way through the energy transition,” Saathoff said, ruling out a drastic increase in carbon prices anytime soon.

The Greens, on the other hand scored their best result ever promising to prioritise rigorous emissions reduction over austerity considerations. Besides higher climate action investments, a higher CO2 price is also a key element of the party’s climate policy. The proceeds from the pricing scheme should be returned to consumers to reduce financial pressure especially on poorer households. Party co-leader and top candidate for chancellor Annalena Baerbock persistently reassured voters before and after the election that the money spent on emissions reduction would ultimately be an investment in a modernised and more sustainable economy that would pay off in the long run.

At a congress of mining union IG BCE, Baerbock sought to alleviate concerns among coal workers that they are no bargaining chips in climate policy by promising to “couple the achievements of a social market economy with ecological aspects.” Germany's welfare system offers a wide range of ways to buffer structural changes, many of which are used already in the existing coal exit plan.

By contrast, the FDP ran on a platform of economic liberalism primarily aimed at reducing taxes and public spending. The party bets on more market-based concepts, for example a general CO2 price in all sectors, to achieve the emissions reduction targets and to benefit everyone in society one way or another. The Free Democrats therefore pressed hard during the informal round of talks to avoid new or higher taxes in the upcoming legislative period, scheduled to last until 2025. The party also insisted that Germany abide by its so-called “debt brake,” a supplement to the country’s constitution that puts tight limits on the money any government can borrow to fund its projects.

Investment or spending? Definitions could decide climate action funding

A “traffic light coalition” would have to find other ways to raise the money needed to finance the multitude of emissions reduction and energy efficiency measures that allow both cutting greenhouse gases across the board and cushioning the impacts on households and businesses. This means that the finance minister, who has veto power on the state budget, will be a pivotal member of the next government. The FDP has stressed that it sees its leader, Christian Lindner, as the most appropriate candidate for the job that is currently still held by chancellor candidate Scholz.

But Green Party co-leader Robert Habeck has also signalled his interest. Some international commentators warned against giving Lindner authority over the budget of Europe’s biggest economy, arguing that the pro-business party leader’s economic policy ideas are “conservative clichés of a bygone era.” Habeck instead won the praise of a group of start-up leaders, traditionally an FDP target group, who argued that the Green politician “understands modern entrepreneurship” and is capable of thinking beyond traditional conflicts.

However, the FDP’s claim to the finance ministry could ultimately prevail given the party’s great emphasis on budget discipline and the option to satisfy the Greens with a novel climate ministry Lindner had hinted at in a rare insight into the coalition negotiations. A climate ministry could aggregate competencies currently spread out over several other ministries and get an important say in bringing general policy in line with the emissions reduction targets. Regardless of who will ultimately be presiding over the individual ministries, the quest for funding climate measures and safety nets to keep all parts of society on board will still be a tough one for each party involved.

In a guideline paper for their delegations seen by Clean Energy Wire, the parties made sure that their negotiating groups for each policy area provide a detailed account of how they plan to finance their respective projects. Each team must list the projected expenditures for each year, clarify whether they will be financed through the public budget or have other sources of funding, and whether their use is “investment-related” or “consumptive.” Deciding on the types of expenditure to fill these gaps is among the most arduous tasks during the talks.

Instead of relying on raising taxes or borrowing, the FDP has called for abolishing some of the many outdated and often climate-damaging subsidies for individual industries, which according to calculations by the federal environment agency UBA amount to 65 billion euros per year. The system that has grown over decades has led many consumers to take permanently lower costs for certain activities for granted. The FDP’s Lindner therefore said he would also oppose doing away with the tax privilege for diesel fuel as well as with the commuter allowance for those travelling longer distances to work, arguing that this would have “the character of a tax rise for the broad middle class in our society.”

Instead, Lindner argued that the buyer’s premium for e-cars could be eliminated to make funding available elsewhere, while his party has repeatedly insisted on comprehensive carbon pricing to reduce emissions. A recent study commissioned by mobility NGO T&E of the party’s proposed schedule found it could let petrol prices spike from about 1.90 euros per litre today to over 2.50 euros, leading the NGO to conclude that a more “ambitious mix” of measures is needed for decarbonising transport.

The proceeds from CO2 pricing should not primarly become a funding source for climate investments either, consumer protection organization vzbv warned. “The government has to reimburse households in full,” the organisation’s energy expert Engelke said. Even if the government reduces power prices by abolishing the renewables levy, this would not be a remedy for many low-income households faced with rising heating and power bills. “Reimbursing would be much more socially equitable,” he argued.

A possible escape route for the coalition partners, at least in the short run, has been offered by the economic research institute ifo, whose president, Clemens Fuest, proposed to use the debt brake’s temporary suspension in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, which allowed current finance minister Scholz to greatly exceed the credit line provided by the brake. “This would be an alternative to shadow budgets, “ Fuest said, arguing that the one-off credit could work as a “business plan for the digital and green transformation.”