Coal exit: elephant in the room at vote in German industry heartland

North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), the epicentre of German industrialisation, is responsible for almost one percent of global annual greenhouse gas emissions and home to more than half of Germany’s total power generation from lignite [See the CLEW factsheet on NRW elections for more data]. The upcoming state elections therefore bear important implications for the entire country’s energy and climate policy.

They are also seen as a bellwether for federal elections in September, political scientist Rudolf Korte told public broadcaster ZDF. Comprising about a fifth of the German electorate, “NRW often has been the key for new political majorities in the country,” he explains.

The region with almost 18 million inhabitants generated seventy-five percent of gross power from coal in 2015. Renewables accounted for about 10 percent that year – far below the country’s average of almost 30 percent.

The vote on Sunday will be of particular importance for the governing Social Democrats (SPD). NRW is a traditional SPD stronghold, but the party has lost two consecutive regional elections against chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservatives (CDU) and slightly polling behind its main contender in the latest survey.

After a defeat in Saarland in March, the CDU scored a surprisingly clear victory in Schleswig-Holstein last Sunday. In the self-proclaimed “cradle of the energy transition”, the Green Party managed to stop a national downward trend, while the Free Democrats (FDP) continued their resurgence by scoring a double-digit result, potentially opening doors for new coalition perspectives on the federal level.

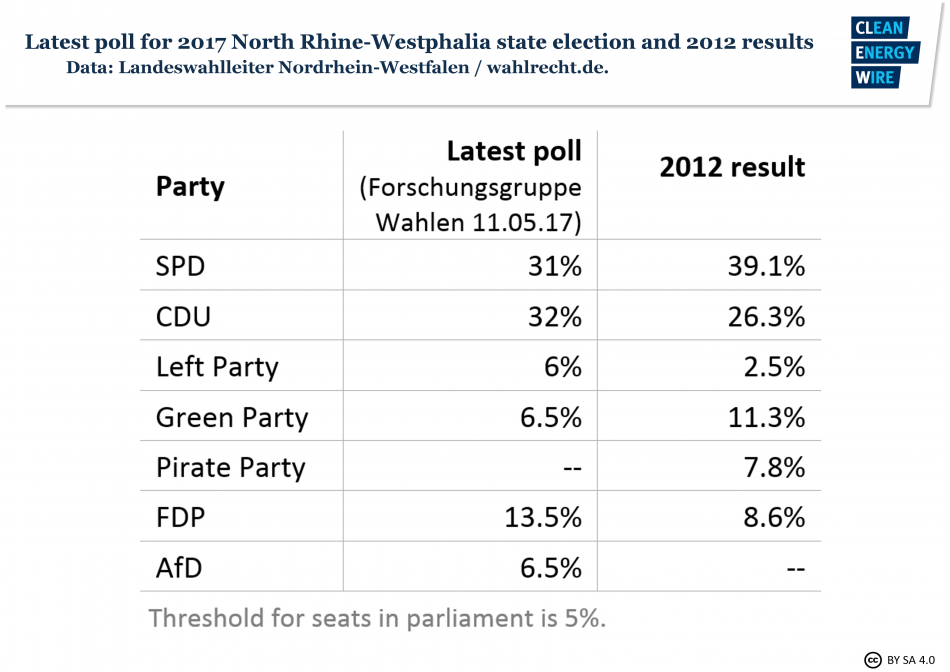

NRW has been governwed by a coalition of Social Democrats and the Green Party under popular SPD-state premier Hannelore Kraft since 2010. But it seems unlikely that the two parties will be able to get enough votes to continue their coalition: Latest polls show Kraft's SPD trailing conservative frontrunner Armin Laschet’s CDU with 31 percent to 32 percent. The Greens in NRW – standing at about 6.5 percent – follow negative national trends and currently are not strong enough to safeguard the coalition.

The vote will be also closely watched for the results of the business-oriented Liberals (FDP) as NRW is the home state of party leader Christian Lindner, who has spearheaded the FDP's resurgence after its failure to enter federal parliament in 2013. Polling at 13.5 percent, a role in the next parliament in Dusseldorf seems to be guaranteed for the economic liberalists. The Left Party and right-wing populists AfD polled at 6 and 6.5 percent respectively.

Climate protection pioneer burdened by lignite legacy

Aware of the state’s hefty share in global emissions, the current government coalition of SPD and the Greens introduced a Climate Protection Law in 2013 to set binding greenhouse gas reduction targets.

North Rhine-Westphalia was the first German state to introduce such a law. It aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25 percent by 2020 and at least 80 percent by 2050, compared to 1990 levels.

Recent federal government reports showed that Germany as a whole will probably miss its 2020 emission reduction target of 40 percent compared to 1990 levels. With NRW being the host region of more than a third of Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions, whatever happens there will have substantial implications for the country’s global image as climate protection pioneer.

“If Germany wants to reach its climate targets, NRW must do its share,” Dirk Jansen, Director of Environment and Nature Protection at Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) NRW, told Clean Energy Wire. “NRW is of central importance. We must exit coal as soon as possible.”

North Rhine-Westphalia, which used to be known as the land of coal and steel, sits on Europe’s biggest lignite mining district. Germany has been the largest lignite producer in the world since the beginning of industrial mining and continues to be among the world’s major coal users to the present day. [Read more about coal in Germany in this CLEW factsheet].

In stark contrast to these facts, “energy policy did not really matter in the state election campaign so far”, Udo Sieverding, Head of the Energy Division at Consumer Association North Rhine-Westphalia, told Clean Energy Wire. In the only TV debate of the parties’ leaders, social democratic state premier Kraft and her conservative contender Laschet made no mention of the future course regarding coal and renewables.

A survey conducted for the state's renewables association LEE showed that 64% of voters polled in NRW wanted more government drive to expand renewables, while 45% felt that the Energiewende and climate protection played not enough of a role in the campaign, with 34% saying the role had been about right.

The campaign largely focused on questions of security and education instead. Energy policy’s legal framework, for example regarding lignite mining, had already been set, according to Sieverding. The political parties did not, therefore, feel the need to place it high on their agenda, he says.

The conservative CDU ruffled some feathers with a campaign poster “Just put your windmills directly in my garden! – We are fed up! We vote CDU”. Green politician and federal MP for the state Oliver Krischer responded on Twitter with a photo of a lignite excavator behind a house in reference to the state’s lignite mining area around the town of Garzweiler.

The state government in 2016 approved a new framework for lignite mining in NRW, which watered down originally-approved plans. The decision brought an end to decades of relocations of entire villages, which had to make room for the open-cast pits. It reduced the amount of mineable lignite but did not include an exit time frame for lignite mining in the state.

“Lignite is the climate killer number one,” says Jansen of the BUND. “For Germany to reach its 2020 emissions reduction target, the country’s dirtiest coal-fired power plants must be shut down fast. And these happen to be located in the Rhenish mining area. That’s the way things are.”

Both SPD and CDU in NRW refuse to talk about an end date for lignite mining and power production. “Regarding a German coal exit, NRW has blocked and stepped on the brakes wherever possible,” Jansen told Clean Energy Wire.

Contrary to its current coalition partners from the Green Party, the SPD opposes a roadmap for ending coal mining in the state: “We don’t need a fixed date but rather a clearly ordered process how to achieve a transition from fossil to renewable energy generation,” the party’s energy expert Georg Fortmeier told national TV station WDR.

Public and corporate finances hinge on successful transition

Much like their main political competitors from the CDU, NRW’s Social Democrats emphasise that a secure and inexpensive energy supply for maintaining the heavy industry’s competitiveness is the state’s key interest. By contrast, the Greens, together with the Left Party, say setting the course for a well-planned coal exit within the next 20 years is necessary to give NRW’s companies planning security that is compatible with national and regional climate targets.

But private businesses are not the only ones in the state that so far have based their budget structure on locally sourced coal: NRW is the home state of Germany’s two largest utilities E.ON and RWE. In spite of the companies’ recently-commenced gradual conversion to more renewable power in their portfolios - in the form of a renewables spin-off called innogy for RWE and a green makeover for E.ON, including the spin-off of its conventional power generation as Uniper - the energy heavyweights continue to rely on coal-fired power plants to a great extent.

And with them are a large number of municipalities in NRW which, due to historical reasons, hold many of the utilities’ shares. The utilities’ woes therefore have a direct impact on public budgets.

“Many municipalities begin to act on their dependence on the large utilities,” Jan Dobertin of the regional renewable energy association LEE says. Local authorities began to think officially about selling their shares of large energy providers as they started transforming from a steady source of income to a growing liability, Dobertin explains.

Dobertin says the state’s reliance on energy intensive industries could even be turned into an advantage by a concerted energy transition: “NRW still is Germany’s fossil power plant hotspot,” he explains. The state therefore had to become “the national hub for flexibility” by providing better demand-side management of its many chemical plants, steel mills, and machine factories. Based on a flexible management of their energy demand, factories could serve as “virtual storage systems”.

Conditions for advancing sector coupling, the interconnection of power production with the energy demand in heating and transportation, were very favourable in the state, Dobertin explains. Advancing combined heat and power generation systems and renewable energies could also make companies pioneers in an efficient and environment-friendly self-sufficient provision, he argues. “NRW could become a frontrunner in this field.”

Achim Vanselow of the German Trade Union Association (DGB) says the transition towards renewables in the state is unlikely to proceed without someone losing out: "There will be no one-by-one transfer of jobs from the old energy world to a new one," he says. He urges politicians to always include job perspectives into their structural change equations and to ensure "a just transition." Vanselow adds that NRW indeed has energy transition lessons to offer for other parts of the world: "As a traditional industry location, we can be a role model for similarly structured regions in Europe, such as Silesia, Yorkshire of Asturia."