Climate targets force trucks into race to clean up transport

Trucks are the undisputed laggard in the global race to make road transport more climate-friendly. But governments' more ambitious policies to cut emissions will now force heavy duty freight to quickly speed up efforts to become more sustainable. Recent research and development advances have made the necessary technologies available, putting the shift within grasp.

The sector has its work cut out. Transport causes almost a quarter of the EU's entire CO2 output, and it is the only sector without any significant emission reductions at all. Trucks and buses belch out around a quarter of those transport emissions, already adding up to some six percent of the EU's total greenhouse gas output. Their share is set to increase further because road freight is growing rapidly, while cars are becoming cleaner as their electrification gathers pace.

As a consequence, the topic of low-emission freight has moved up the agenda. In Europe, new EU fuel efficiency rules for trucks prescribe sharp emission cuts for the first time, and are set to trigger a transformation in the sector, akin to that shaking up the car industry.

"The EU's new emission regulation for heavy duty vehicles has finally fired the starting shot for the decarbonisation of trucks. It has triggered a race among truckmakers to get low-emission vehicles market-ready," mobility researcher Florian Hacker from the German sustainability think tank Oeko-Institut told the Clean Energy Wire.

The EU rules adopted in 2019 say that from 2025 onwards, newly registered trucks must have 15 percent lower emissions, and from 2030 onwards 30 percent. "The 2025 target can be achieved using technologies that are already available on the market," the EU said, hinting at possibilities to make conventional trucks more efficient.

But reaching the 2030 target will require a much more profound shift to alternative propulsion technologies, according to experts. "The 2030 CO2 regulation has effectively sealed the combustion engine's fate," Hacker said.

Only a few years ago, many experts had serious doubts about the technical feasibility of the rapid and deep emissions reductions that now lie ahead. But a whole range of technologies to clean up trucks is becoming available: Battery-electric drivetrains, hydrogen fuel cells, catenary systems and synthetic fuels made with green electricity.

This development has triggered a flurry of research. "There has been a surge in the number of reports published on ways of decarbonising the road freight sector - it's a very popular subject," says Alan McKinnon, a professor at Kühne Logistics University in Hamburg. He points to a whole range of recent publications from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the OECD's International Transport Forum, the non-profit Smart Freight Centre, and clean mobility NGOs such as Transport & Environment and the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

Batteries emerge as frontrunner

The recent spread of battery-electric drivetrains into heavier vehicles in particular has stoked optimism that the shift to clean road haulage has become feasible. Lighter commercial vehicles have already entered the transition in great numbers. For example, Amazon last year ordered 100,000 electric delivery vans from Rivian, a Michigan-based start-up founded by MIT graduate Robert “RJ” Scaringe in 2009, in a push to make the company's fleet run entirely on renewable energy by 2030. For its European delivery fleet, the online retailer ordered 1,800 electric vans from Mercedes Benz.

Only a few years ago, heavy long-haul trucks powered by batteries were considered a pipe dream due to heavy battery weight constraints. But thanks to improving technology, these are also starting to become available. Echoing the transition in cars, Tesla is leading the way with its Semi electric truck, which marks a distinct departure from conventional truck designs. The Californian company plans to start volume production of the vehicle in 2021, and has already bagged some large orders – Walmart Canada, Pepsi and UPS have each ordered at least 100 Semis.

As was the case in the car industry, established truckmakers have started to offer electric versions of their existing conventional models. Swedish Volkswagen subsidiary Scania launched fully electric trucks designed for urban distribution in a "commitment to long-term electrification," said Scania CEO Henrik Henriksson. "In a few years, we will also introduce electric trucks for long-haulage that are designed for quick charging during the mandatory 45-minute rest periods for drivers," he added. Rival Volvo also said in November it will launch a full range of battery-electric trucks this year.

These offerings show that lowering emissions in trucking has already turned into a competitive question for truckmakers. "The manufacturers know that they must be on their guard if they want to play a role in future world markets," according to Hacker, who is in close contact with the industry.

Initially, it will be a challenge to find buyers for new electric trucks, as the trucking industry runs on thin margins and has a reputation for being risk-averse. Industry experts see this as a hurdle in the first stages of a shift to low-emission vehicles.

"In general, there is still fairly deep scepticism in the trucking industry of whether the technology actually works," Morgan Stanley transportation analyst Ravi Shanker told The Wall Street Journal.

Public procurement currently leads the way in cleaning up heavy vehicles, as public authorities invest heavily in electric buses around the world, for example. The number of e-buses has risen to around 4,000 in Europe – compared to roughly 400,000 in China. In the largest order for pure electric buses outside of China, Chinese carmaker BYD won a contract in early 2021 to supply 1,002 battery-electric models to Colombia's capital Bogota.

But the haulage industry's focus on low costs could strongly work in favour of the transition at a later stage, given that electric trucks are very cheap to run thanks to comparatively lower energy and maintenance costs, according to sustainable vehicle expert Auke Hoekstra, a researcher at Eindhoven University of Technology.

"I think that within five years, we will have 40-tonne battery semis with 800 km of range that could carry more cargo than conventional trucks," Hoekstra told the Clean Energy Wire in an interview. He added that a limited need for long driving ranges, simple and cheap charging solutions and the absence of weight disadvantages in entirely redesigned trucks "will soon form a convincing business case for battery-electric trucks in the calculations of freight companies."

Hoekstra anticipated that the appearance of electric trucks on the roads in the coming years will considerably speed up the transition within truckmakers. "Suddenly, all those people who say 'it cannot be done' within truck companies will hear their boss replying: 'Well, our competitor can do it – so you will have to do it, too'," he said.

Hotly contested: Hydrogen fuel cells

Some truckmakers also continue to bet on fuel cells instead of batteries to power the electric motors of their vehicles. Fuel cells offer some obvious advantages, such as quicker refuelling times and longer ranges, but it will still take a few years to get them market-ready.

In November, Volvo and Daimler Truck signed a binding agreement for a joint venture to develop, produce and commercialise fuel cell systems for use in heavy-duty trucks. "The ambition of both partners is to make the new company a leading global manufacturer of fuel cells, and thus help the world take a major step towards climate-neutral and sustainable transportation by 2050," Daimler said.

But an increasing number of experts voice doubts that fuel cells will be a viable mainstream alternative to batteries for two main reasons. Firstly, they argue that the trend towards battery-electric drives has already become self-reinforcing. Huge amounts of money flow into battery research for cars, increasing the chances that the technology will rapidly improve further and become cheaper, making it increasingly difficult for fuel cells to catch up.

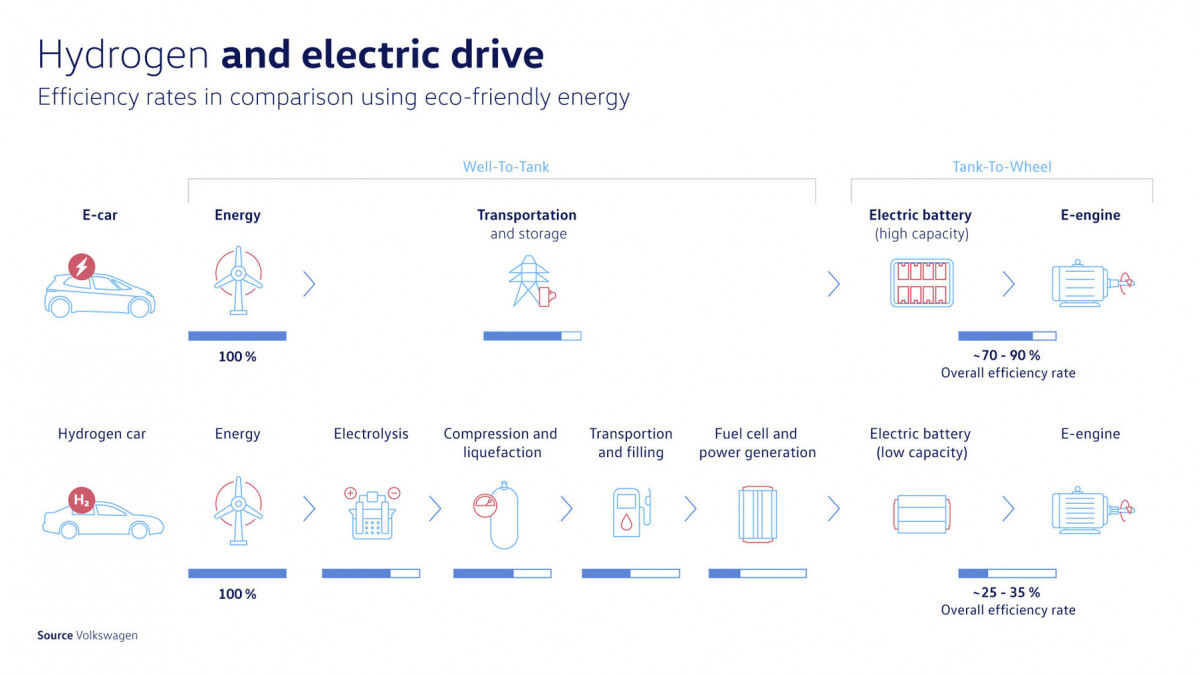

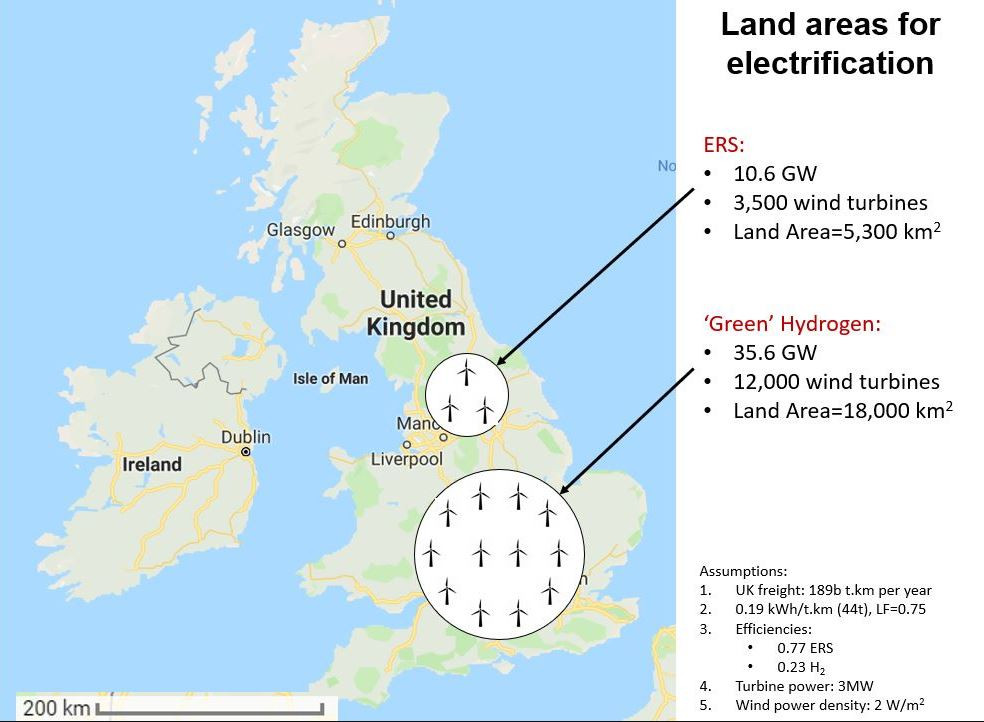

A second major drawback is that battery-electric vehicles are inherently more energy-efficient than fuel cells. Because of conversion losses in making and using hydrogen, it takes two to three times more energy to power a fuel cell vehicle than a battery-electric one. This will probably make them more expensive to run. It also constitutes an environmental problem: More renewable installations will be needed to operate them, while batteries mainly cause environmental damages during their energy-intensive production.

Hoekstra and many other experts warn that zero emission hydrogen made with renewable electricity will remain a scarce and therefore expensive resource. "We only have a limited amount of green energy, and there are much better uses for hydrogen than putting it in a truck – for example, it can be used for decarbonising industry and aviation," Hoekstra said.

Catenary systems could be a joker, but need rapid government support

The most energy-efficient solution would be to power electric trucks with overhead lines, eliminating the need for large and heavy batteries. Germany, Sweden and California already run pilot projects to test the technology, but a large-scale roll-out would have to overcome a chicken-and-egg problem: Trucking companies won't buy catenary trucks without the infrastructure in place, and there is little incentive to build so-called e-Highways as long as there are no catenary trucks around to use them.

"A rapid rollout of a large-scale test infrastructure will be decisive if catenary trucks are to remain in the technological race," transport economist Carl-Friedrich Elmer from the sustainable transport think tank Agora Verkehrswende told the Clean Energy Wire. "If the government builds a few hundred kilometres of overhead lines within the next years, catenary systems still stand a chance. If not, the technology is likely to disappear from the menu."

Synthetic fuels: Tempting but highly inefficient

Germany's car industry association VDA and the country's mineral oil industry association MWV also lobby for using renewable fuels made with clean electricity (often referred to as e-fuels or synthetic fuels) in combustion engines. From the industry perspective, e-fuels are a tempting proposal: Much of the existing technology and infrastructure – such as petrol stations - could remain unchanged and the technology could throw a lifeline to a supplier industry specialised in combustion engine technologies, such as spark plugs, crank shafts, gearboxes and exhaust systems, which employs hundreds of thousands of well-paid workers in Germany alone. These advantages partly explain why car industry association VDA insists that "The problem is not the combustion engine but the fuel."

But synthetic fuels' energy balance is even far inferior to that of fuel cells. They require more energy-intensive conversion steps, and even modern combustion engines convert less than half of the fuel's energy content into motion. These disadvantages make even oil major Shell sceptical. "Of course, we can produce low emission fuels. But if, in the end, the various conversion steps mean that only ten percent of the primary energy can be used for propulsion, I have to ask myself two questions: How sustainably have these 90 percent that are lost in the conversion process been produced? Even if we can answer this question sensibly: How expensive was it and who will pay for this effort?," Jan Toschka, who heads the company's filling station business in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, told the clean mobility specialist website electrive. He added: "We do not win a prize by offering solutions that make no economic sense or are not really applicable from an environmental perspective."

No one-size-fits-all

Germany's freight transport association BGL says it remains uncertain which low-emission technologies will gain the upper hand. "There is currently great uncertainty about where the journey will take us by 2030," association head Dirk Engelhardt said, adding that investments in climate-neutral truck technologies urgently require planning and investment security.

Germany's automobile industry association VDA and many industry players say that a clean road transport system will rely on a variety of technologies. "In the future, the world will be powered by a combination of battery-electric and fuel cell electric vehicles, along with other renewable fuels to some extent," said Daimler board member Martin Daum.

Logistics expert McKinnon tends to agree. "Looking overall at these options, I don't think any single one is going to triumph. It seems to me there is no one-size-fits-all. These different powertrain technologies will probably coexist and compete," McKinnon says, adding that the various technologies have different "operational sweet spots," depending on payload weight and trip length.

Transformation pressure builds up rapidly on all levels

The new EU emission rules for trucks are currently the largest lever to clean up heavy-duty freight transport, but policy carrots and sticks at the national, regional and local level also have an important role to play.

The largest EU member Germany, for example, has set itself the target of reducing total transport emissions by around 40 percent within a decade. The government's climate protection programme stipulates that in 2030 one-third of the mileage is to be covered by electric trucks or electricity-based fuels.

The country has recently agreed on a bundle of measures to support this shift. It will spend more than one billion euros to subsidise up to 80 percent of the additional costs for low-emission vehicles compared to diesel trucks in the next three years. The transport ministry also said it will manage the installation of the charging and refuelling infrastructure needed for commercial vehicles with alternative drive systems, and advocate a reform of the country's truck toll system to take account of CO2 emissions.

Over the coming three years, the country wants to test battery electric drives, hydrogen fuel cell drives and catenary systems in preparation for a large-scale roll-out starting from around the end of 2023.

Sub-national actors, such as cities, can also be crucial agents for change. In the fight against local air pollution, major cities, such as Paris, could extend their plans for a ban on combustion engine cars to trucks as soon as clean alternatives become available.

"At present, they simply don't have the option because there is no alternative to the diesel truck – the goods simply wouldn't get delivered to the stores. But as soon as that alternative appears, some municipalities could act very aggressively," argues Hoekstra.

Last but not least, the rapidly increasing number of company commitments to sharp emission reductions could boost the shift. For example, German logistics company DHL Group says it wants to reduce all logistics-related emissions to zero by 2050.

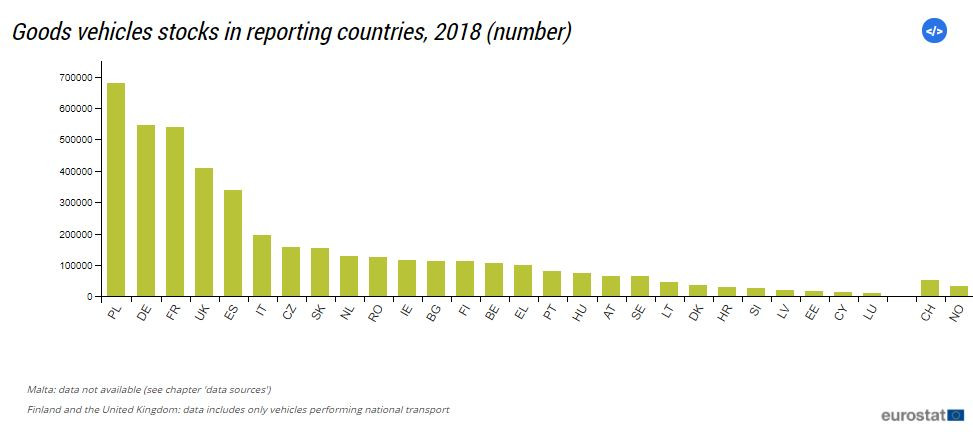

4.3 million existing problems

But even ending the sale of polluting conventional trucks leaves a massive problem on Europe's roads: Its existing fleet of more than four million goods vehicles. At current renewal rates, exchanging Germany's truck fleet will take about ten years, while an overhaul of Poland's fleet, the largest in Europe, will last 22 years, according to McKinnon. The EU average is about 13 years – meaning combustion engine trucks are here to stay for many years.

"One could accelerate that replacement rate for trucks by using regulation or government financial incentives, but I think there will be forces pushing in the opposite direction, because as the haulage industry emerges from the Covid crisis, many of them will be in a bad state financially, and that may result in companies extending the replacement rate of vehicles," says McKinnon. Citing the initially higher costs of low-carbon vehicles, uncertainty about their second-hand value, and infrastructure provisions, he adds that "It's not difficult to construct a fairly pessimistic scenario for this dramatic transformation of road freight operations away from fossil fuels towards low-carbon vehicles."

Other options to lower emissions

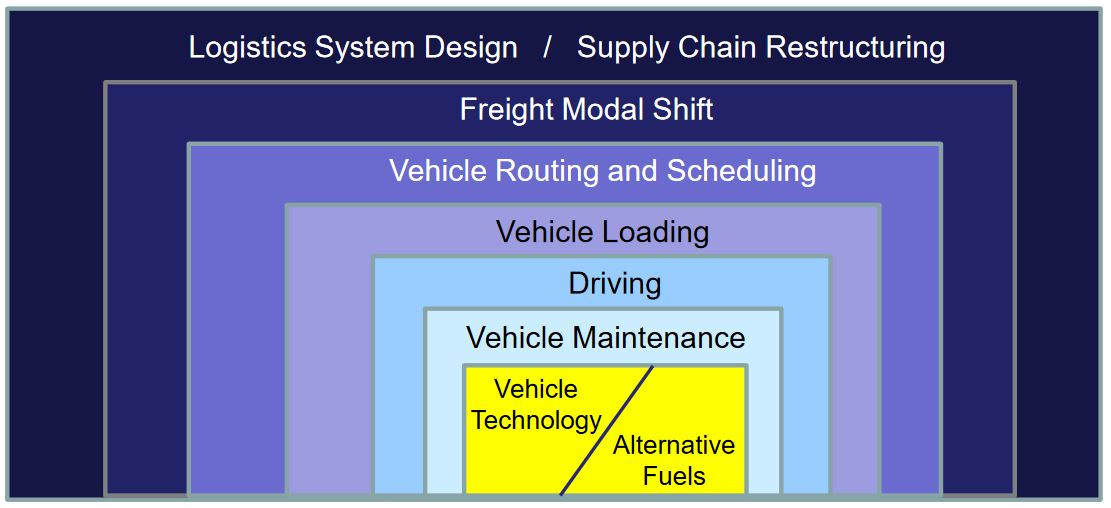

Removing fossil fuel-powered trucks from the roads will be the key to reaching climate targets in the long run. But there are many other steps that can be taken in the meantime to make the sector cleaner.

Some of the road freight can be transferred to rail, for example. Optimising logistics management via digitalisation also offers significant potentials, given that almost 30 percent of trucks run empty. Training drivers to use as little fuel as possible is often seen as one of the easiest and cheapest options to lower road freight's climate impact. Trucks can also be redesigned to reduce fuel consumption, and new regulation on weight and size limits could increase efficiency.

Each of these individual measures might only constitute a small step towards greening heavy duty freight. But added up, their impact would be significant. A lot remains to be done by policymakers, haulage companies, truckmakers and others before truly clean trucks take over.