Choice of candidates to kick off German chancellor race

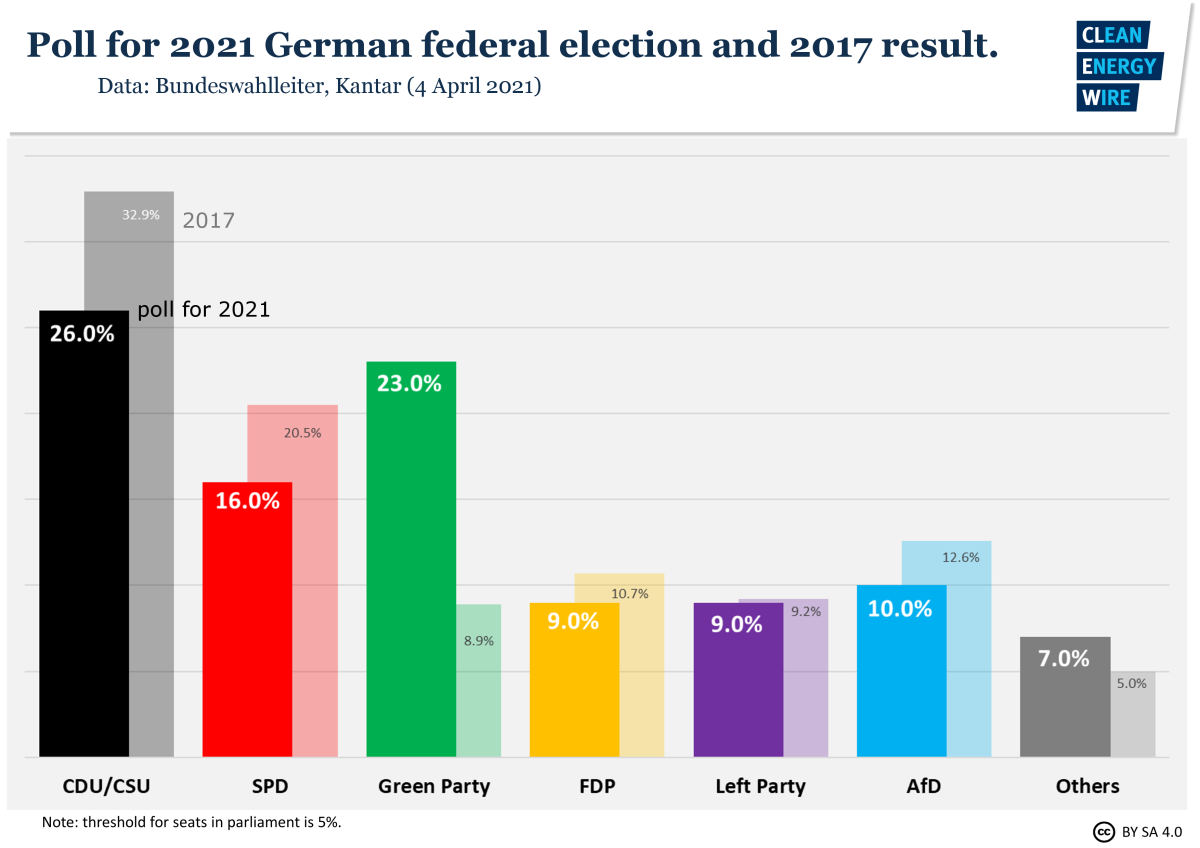

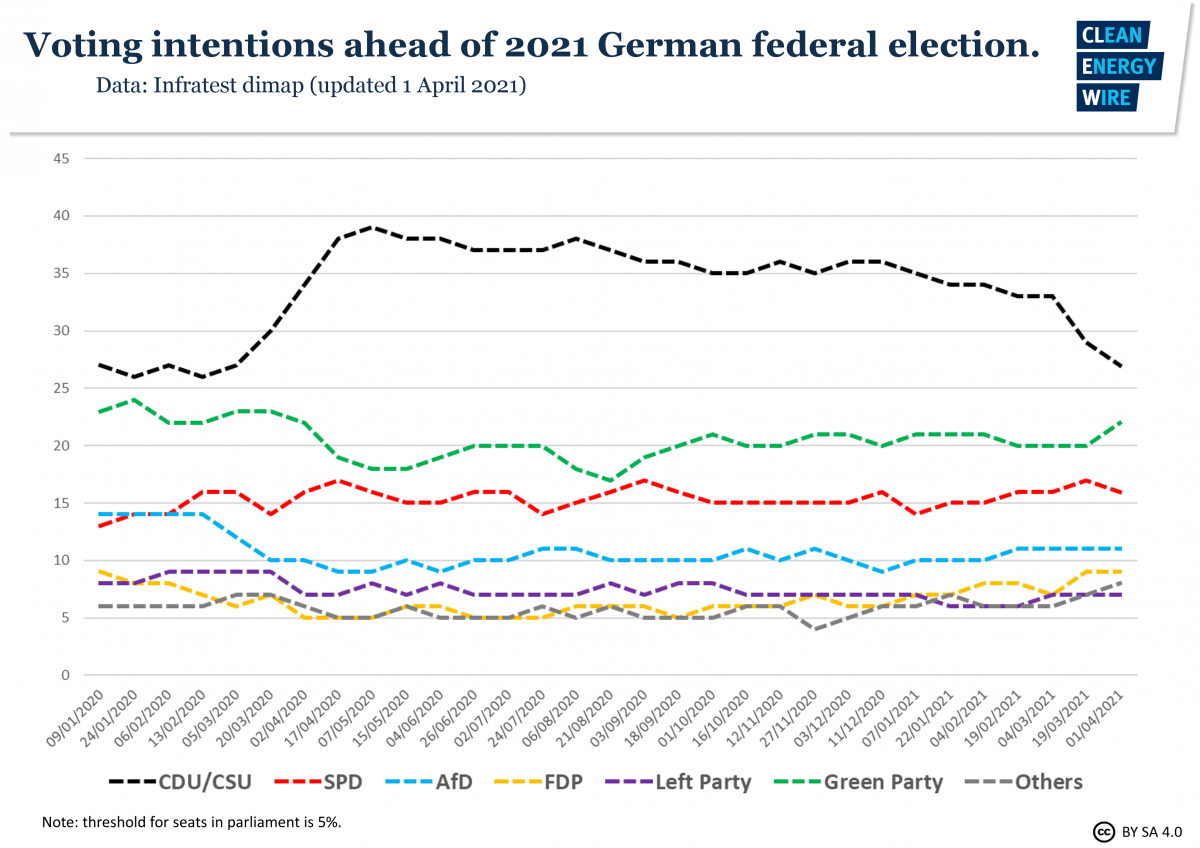

Germany’s conservative CDU/CSU bloc and the Green Party are set to choose their lead candidates for the national vote in September. The decisions will kick off an election race with an increasingly uncertain outcome, as a lobbying scandal and the coronavirus pandemic are changing voters’ opinions by the week. Having led the polls for most of the past three years, the two camps are most likely to provide current chancellor Angela Merkel’s successor and thus shape the political future of Europe’s largest economy. The country has firmly set sails for climate neutrality by 2050 and the next leader will almost certainly pursue that goal, but the election outcome could prove critical for the speed of the energy transition in this decade.

Merkel’s ruling conservatives still lead the polls, but have been dealt heavy blows by both a lobbying scandal involving key climate and energy MPs and missteps in handling the pandemic and its effects. A growing rift between CDU leader Armin Laschet and his top rival in the chancellor race CSU head Markus Söder further complicates an already difficult choice of who should lead the group into the September election. For the Greens, on the other hand, the choice is not tainted by a public quarrel. Party co-leaders Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck have said the candidacy is for the two of them to decide. The Green Party has announced that its leadership will present its decision on 19 April, and the final candidate will be chosen by delegates at a party conference on 11 - 13 June.

On 26 September, Germany will head to the ballots to elect a new federal parliament and thus determine which party will lead the next coalition government and shape the country’s climate and energy policy. The vote will conclude a pandemic-dominated ‘super election year’ packed with six state elections, during which climate change looms larger than arguably any time before. The conservatives and the Green Party have announced they would present their chancellor candidate sometime between Easter and Pentecost at the end of May. Several politicians have called on Laschet and Söder to decide sooner rather than later to rally the troops and start to focus on policy.

Germany is traditionally governed by a coalition, because usually no single party gets an absolute majority in the elections. An alliance of conservatives and Greens has long seemed the most realistic option. As the CDU and CSU drop in the polls, other coalitions – even without the conservatives’ participation – become possible, such as Green Party/Social Democrats (SPD)/Left Party, or a “traffic light coalition” of Greens/SPD/pro business FDP (the name derives from the traditional party colours). The chancellor is elected by the majority of MPs in the Bundestag once the coalition is agreed.

Contest within conservative block

CDU delegates elected Laschet, 60, as the party’s new leader at the beginning of this year. This position has usually meant chancellor candidacy of the conservative CDU/CSU alliance as well, as the CDU is far bigger than the CSU. However, voters don’t appear to see the centrist and Merkel ally Laschet as a good chancellor candidate. His approval ratings trail far behind those of Söder and the leaders of the other parties. In addition, Laschet has come under fire for mishandling the coronavirus crisis in his state – even chancellor Merkel criticised Laschet for not being strict enough. Söder used this to take a jab at his rival. “It feels very strange when the CDU chairman quarrels with the CDU chancellor half a year before the federal election,” he said.

CDU leader Laschet continues to be premier of the country's most populous federal state, North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), and his energy and climate policy record is regarded as somewhat ambiguous. He has drawn criticism for his handling of climate protests in the context of Germany's coal exit. Lignite mining state NRW, home to Germany's largest energy company RWE, has been a key battleground for the brokering of the phase-out.

Laschet – who has invoked his father’s job as a coal miner to emphasise his working-class background and dependability – has been criticised for his generous stance on granting coal companies comfortable compensation payments, his defence of the newly opened NRW coal plant Datteln IV, and his government's handling of the protests in the Hambach forest near the Garzweiler lignite mine. However, he has moved on to an optimistic narrative that the core state of German heavy industry looks to a bright future based on the production and advanced use of green hydrogen. [Find out more about Laschet and his energy and climate ambitions in this article.]

Laschet – who worked as a journalist before entering politics – portrays himself as a man of compromise. He has long tried to counter his „nice guy” image. He told Bild Zeitung: “I have been engaged in international politics for many years and would be able to stand up to other statesmen thanks to this experience.” His time as a member of the European Parliament for several years might come as an asset in talks with European Commission head and fellow CDU member Ursula von der Leyen about details of the bloc's Green Deal, the EU programme to become the first climate-neutral continent. “Europe - that's what my heart beats for,” he said during an event kicking off a stakeholder process to develop the CDU’s election programme.

The “greening” of Markus Söder

On the other hand, Söder, 54, head of the CDU's conservative Bavarian sister party CSU, has been firmly rooted in his home state and became a member of his party at the age of 16. He has so far refrained from officially throwing his hat into the ring, but he is widely seen as one of two options for the conservatives. In an interview with Bild, Söder said it would have to be a joint decision with Laschet and polls “of course play a role.” “We must consider what is best for Germany and the [CDU/CSU] union,” he told the newspaper.

During his time as secretary general of the Christian Social Union, which has governed the southern German state non-stop since the 1950s, he was seen as an agitator, but his behaviour softened somewhat once he became part of the government and later the leader of his party. The Bavarian state premier is known for his populist politics- -- he has an open ear for what his voters want. A key example is his stance on climate action.

Following droughts and heat waves in 2018, the Greens attracted hundreds of thousands of votes from former CSU and SPD supporters in the regional election in Bavaria that year, prompting Söder to identify the party as the conservatives’ main competitor henceforth. “Bavaria can become greener, without the Greens,” he said. In the following weeks and months, he presented a government programme with a focus on climate, made recurring publicity visits to Germany’s highest peak, the Zugspitze, to highlight melting glaciers and climate change in general, and called for an accelerated German coal exit – a move that was fairly easy for him, as there are no active mines in his state and it would not benefit from federal payments to affected regions.

Media, other politicians, industry and voters have speculated about whether the “greening of Markus Söder” was based on true convictions or strategic considerations. However, this discussion is nothing new. Already during his time as state environment minister about ten years earlier he was faced with the same scepticism, after criticising plans to upgrade the Danube waterway against his party’s official position.

An amicable affair and difficult choice for the Greens

In contrast to the battle within the conservative bloc, the "power struggle" in the Green Party has been an extremely amicable affair. Party leaders Annalena Baerbock, who served as the parliamentary group's speaker on climate issues, and Robert Habeck, a former energy transition minister in Germany's northernmost state, will agree amongst themselves who will run for chancellor.

Naming a Green candidate for the first time was initially seen as a PR stunt but has become a serious issue given that a Green chancellor has become a real possibility – it would be a world-first for a major economy. Since Baerbock and Habeck took charge of the Greens in early 2018, the party has surged in the polls, leaving the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD) far behind.

Both politicians hail from their party’s moderate wing, which makes programmatic differences between the two hard to spot – the choice is between personalities. Baerbock is a 40-year-old career politician with a reputation for prudence and diligence. As a climate expert and MP for the eastern German coal state of Brandenburg, she gained recognition during Germany's coal exit negotiations. Baerbock has been described as "media-savvy and charismatic" and despite her lack of government experience, the former youth elite trampolinist says that "three years as a party leader, member of parliament and mother of small children" show she is tough enough to run the chancellery.

The 51-year-old Habeck started his professional life as a writer, and German media have characterised him as the perfect son-in-law. His stint as energy transition minister in Schleswig Holstein, one of Germany's most important wind power states– a wide-ranging job that also put him in charge of agriculture and fishery – gave him government experience and is generally seen as a success, but he is slightly gaffe-prone. This is why picking Habeck as a candidate is seen as a risky bet by some party insiders, while Baerbock counts as a safe pair of hands, but with possibly smaller chances of becoming chancellor.

Social Democrats less likely to win chancellorship

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) has not managed to recover from its plummeting poll numbers ahead of the 2017 election and have trailed behind the Greens for most of the past two and a half years. Unless the party manages to overtake the Green Party in September, there is little chance for it to take over the chancellery. Still, the Social Democrats were the first of the major parties to nominate their candidate: finance minister Olaf Scholz.

Scholz, an employment lawyer with his own law firm, former mayor of Hamburg and federal employment minister in a previous Merkel cabinet, is seen as a very pragmatic and uncharismatic politician. His record as finance minister since the current coalition government took office in 2018 can be described as very solid. His poll numbers throughout the coronavirus crisis remained high, as he comes across as a very level-headed manager of the ensuing financial turbulences.

He has not yet made a name for himself within the field of climate action and energy policy, and has on occasion ranked the concerns of the (car) industry and other companies higher than environmental and climate issues. Over this and other aspects of making emissions more expensive, he has clashed with fellow SPD minister for the environment Svenja Schulze. On other occasions, however, he has backed up the environment ministry’s climate plans. When implementing the national CO2 price for transport and heating fuels, Scholz was an advocate of starting with a reduced price so as to not overburden households and companies.